NEO PROPAGANDA

#3 in a series of blogs on what to expect in Tibet in 2022

In 2022 Chinese Communist Party propaganda is no longer what we expect.

Habitually, we assume China’s propaganda to be like the bold posters of the 1950s celebrating heroic model workers, glorifying hydro dams and smoking factory chimney stacks.

Or we expect more recent propaganda to proclaim China’s achievements, in outer space and on the deepest ocean floors, in stunning action movies featuring wolf warrior heroes battling the forces of darkness.

Above all, we expect propaganda to be words, slogans, memorable phrases, commanding us to rectify our thinking and concede China is right about everything.

Much, much more indepth analysis of CCP propaganda at https://decodingccp.org

But propaganda can be subtler than that, and a whole lot more persuasive. It can be fronted by the kind of engaging online influencers we can all identify with. We like the messenger, so we like the message.

We like that we can see for ourselves how it is for the people of China, we can witness what brings them happiness, we can project our selves into scenes of joy and positive energy 正能量 zhèng néngliàng.

No longer are we being instructed what is the correct line, nor is our belief in inborn, universal human rights frontally attacked, denouncing us as part of a global neo-imperial conspiracy to weaken and control China.

We call them influencers. China, even in Chinese, calls them KOLs, which grandly means Key Online Leaders 关键在线领导者 guānjiàn zàixiàn lǐngdǎo zhě. If you think influencers on social media are big deals, the KOLs are even bigger.

We call them influencers. China, even in Chinese, calls them KOLs, which grandly means Key Online Leaders 关键在线领导者 guānjiàn zàixiàn lǐngdǎo zhě. If you think influencers on social media are big deals, the KOLs are even bigger.

China’s Key Opinion Leaders may well find a new niche, this time much more tightly conforming to official agendas. That includes taking the lead in spreading propaganda, and selling official slogans such as China as a better democracy than the US.

What is a KOL? How do they persuade us? How do they perform themselves to perform their selling of stuff? How do they skilfully weave in and out of our many cognitive biases, whether they are daigou selling NZ butter, or boy-girl lipstick, or the latest CCP slogans? These are no longer questions only for Chinese citizens targeted by those winsome KOLs, there is increasing use of KOLs as global influencers pitching CCP slogans.

Jiarui Sun, University of Chicago, tells us: “Beijing’s propaganda strategy is shifting from a top-down dogmatic style into one that is constantly in negotiation with the audience.” CCP deployment of “meng language [of cuteness] shifts the textual propaganda language into a visual one which then alters the traditionally masculine militaristic propaganda language into a feminine one that takes place in a private realm, resonating with the online audience at a personal level. By addressing the viewers’ emotions and feelings, the meng [cute] nationalism gains from this audience a deep identification with the state. By utilizing affective cultural products such as animation, fandom culture, and sentimental documentaries, the propaganda apparatus produces a Pink Cyborg whose technologized feminine gaze creates what I call meng patriotism, a soft yet influential collective mentality propagated across the Chinese Internet that is nationalist, personal, and yet powerfully militaristic.”[1]

Throughout its history the CCP has shifted shape, read the winds, adapted to new circumstances in order to perpetuate its power. This latest shift is from textual to visual, from declamation to behavioural nudging, crossing genders, going online and even into the metaverse.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QaGfgprc7q0

PERSUASIVELY PERFORMING PROPAGANDA

On 5 January 2022 all the top propaganda officials met in Beijing for the latest instructions. The language of the official outcome was, as usual, a series of commands, and repetitive cliches: “We should guide the broad masses of cadres and people to consciously be firm believers and faithful practitioners of the party’s innovative theories. We should hold high the banner of thought, gather the strength to forge ahead, cultivate the soul of a strong country, lay a solid foundation for security, and play the voice of a strong China. We should increase the supply of high-quality cultural products and services to provide more and better spiritual food for the people., and inspire the broad masses of cadres and people to forge ahead with confidence in a new journey and contribute to a new era.”

Nonetheless, at the retail level, those cliches vanish, are given new life, in new media and new formats.

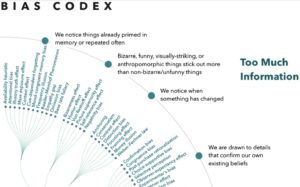

Influencers hooked by this CCP shift into behavioural psychology are in turn motivated to post and tweet their patriotic thoughts, encoding a pink sensibility, and the gamut of emotions everyone has towards engaging young women. The entire rotating wheel of cognitive biases is in play, the full 200 delusions we habitually take -usually subconsciously- as reasonable decisions about right and wrong.

Facing, as usual, too much information, not enough meaning, yet the need to act fast, we identify with that likeable young woman and buy her message, then never think about how we got there, or what we need to remember. This is the cognitive bias codex of short cuts and emojified likes that we think constitutes reason.

Starting with the behavioural economist who won a 2002 Nobel Prize for noticing the ways we make our economic decisions are delusional, there has been a blossoming of insights into the full range of over-simplifications we turn to, as the basis for deciding anything. That wheel now has 200 spokes, each one naming a psychological label for the many ways we routinely edit out most of the subtleties of interconnectedness of ever-shifting reality. Homo sapiens, the wise monkey, we are not. Read the full 200 and weep.

The Buddhists got there a lot earlier, with as many as 84,000 delusions, which also make for 84,000 entry points to awaken to inconceivable reality. The historic Buddha didn’t attempt to name all the delusions, and managed to convey how they work without needing psychologisms such as status quo bias, system justification, sunk cost fallacy, zero risk bias, hyperbolic discounting, trait ascription bias or false consensus effect, to name a few. The point is we just keep going round and round, wandering endlessly, forever hoping it will all turn out well.

It is precisely these cognitive biases the CCP propaganda machine has embraced and increasingly deploys, personifying its jargons as the spontaneous, authentic truths spoken by the most likeable of KOLs.

It is precisely these cognitive biases the CCP propaganda machine has embraced and increasingly deploys, personifying its jargons as the spontaneous, authentic truths spoken by the most likeable of KOLs.

To become a KOL, you need first of all to know how to perform your chosen self, to the camera. That persona should brim with positive energy™, both because that is what the CCP explicitly demands, and because it is what we all want to see. You have to be fun to be with, open, light, able to make fun of yourself.

One of the most skilful of Xinhua KOLs, Miao Xiaojuan, elicits trust effortlessly. Learning how to ski, she begins a tweet: “Successfully bruised my ego in front of the camera”. You gotta like her. The girl has such openness. So when she takes us on a tightly edited Xinhua tour of Tibet, Xinjiang and much of China, over 100 images in 120 seconds, you gotta like her, and her message that it’s all good, everyone is prospering, everyone has freedom, everyone is smiling. What’s not to like?

One of the most skilful of Xinhua KOLs, Miao Xiaojuan, elicits trust effortlessly. Learning how to ski, she begins a tweet: “Successfully bruised my ego in front of the camera”. You gotta like her. The girl has such openness. So when she takes us on a tightly edited Xinhua tour of Tibet, Xinjiang and much of China, over 100 images in 120 seconds, you gotta like her, and her message that it’s all good, everyone is prospering, everyone has freedom, everyone is smiling. What’s not to like?

In short or longer form, she always is easy to like, switching effortlessly from coastal café owners to temples in Lhasa to show us there is religious freedom throughout China. She chats with Angon Rinpoche’s son Balog Rinpoche, of the Drigung Kagyu Yangrigar seat, near Lhasa, who tells us all is well for religious freedom. Miao Xiaojuan is so relaxed, conversational, informal, open; it’s only natural you trust her. Dozens of cognitive biases are in play.

She tweets: “We spent so much time and efforts on this #humanrights documentary. The one-hour version will come out tmrw. I would be thrilled if our work could help understand China just a bit better.”

This is the future of CCP propaganda. The parallel universes run smoothly alongside each other. We can all relax; everything is OK in China, and the folks there are really just like us, working, worshipping, getting on with life. It’s all good.

We might even be open to the long form, the 60 mins tour, just as crisply edited, with time for an authenticating moment of sadness too, as we visit a home for disabled kids, but look how lovingly they are cared for, and in Xinjiang. That sad moment does much for authenticity, this is nothing like in-your-face propaganda. The legislative voice is gone, the hectoring, self-righteous tone is gone, the demand to be heard has vanished; instead we can see for ourselves that it’s all good. We can relax, we aren’t being yelled at.

All those energetic ordinary folks, gesticulating, smiling, arguing, it’s all so normal; in fact it does add up to a whole-process democracy, a real democracy, everyone has a voice.

On this six week filming trip for a 60 mins cut, she has travelling companions, fellow travellers we can identify with, three American men, to help us bridge, and enter those Chinese landscapes without any of it feeling a bit Other.

PROPAGANDA IN THE COMING METAVERSE

Turning propaganda from text into video, from stolid Foreign Ministry lectures to engaging young women influencers, isn’t at all where propaganda morphs to and then evolves no further.

Propaganda personalised by Key Opinion Leaders is not the ultimate destination, there is much more to come.

In the nearish future, CCP propaganda will be fully immersive, embedded in the metaverse, seductively personalised, a patriotic gamerworld in which you, the user, get to see yourself as your online avatar, personally battling the evil Americans to assert China’s discourse power.

China has the gaming culture already, with an amazing 720 million registered gamers. China has the game developers, the corporate giants, notably Tencent and ByteDance, that make huge profits from addictive gaming. China has the regulatory muscle to make Tencent fulfil the party-state’s need to weave its propaganda messages into the games. China is chasing the metaverse, in which the gamer headset you wear also has tiny cameras focussed on your eyeballs, tracking all eye movement, brightening the clours of what you linger on, seducing you into an immersive virtual world you think you control, while it controls you.

China has the gaming culture already, with an amazing 720 million registered gamers. China has the game developers, the corporate giants, notably Tencent and ByteDance, that make huge profits from addictive gaming. China has the regulatory muscle to make Tencent fulfil the party-state’s need to weave its propaganda messages into the games. China is chasing the metaverse, in which the gamer headset you wear also has tiny cameras focussed on your eyeballs, tracking all eye movement, brightening the clours of what you linger on, seducing you into an immersive virtual world you think you control, while it controls you.

Right now, that prospect is still far from reality, but a lot of real money and talent is going into making it happen, in both of the parallel universes, of China and rest of world. Facebook is busily patenting technologies to detect slight shifts in body posture, a wrinkling of the nose, widening or narrowing of the eyes; all to identify your emotions and instantly change the plotline of the story game you are immersed in, with you as the action hero inside it. Chinese tech is similarly on a fast track to invent, own, deploy and profit from such capabilities.

The difference is that Facebook will make money by selling your eyeball movements to advertisers who will instantly place enticing merch right in front of you, inside the gameworld; while the CCP will reward you, player one, with social credit for making the party’s mass line your own, then deploying it to defeat the enemy.

Either way you, the user, are being used, to achieve the ends of the biggest gamers in town, whether American tech titans, or the CCP apparat. They write the games, they control the tech, they will sell us the fancy headsets at a deliberately low price because we are the product, we are the source of endless streams of data points that can be fed into the algorithms that end up with us buying more stuff, or buying the party line.

In 2021 the party-state got Tencent exactly where it wants it. The official crackdown on the number of hours registered users can go gaming, wiped billions from the capital valuation of Tencent, leaving it eager to display compliance with whatever Beijing wants.

China’s powerful Ministry of Industry and Information Technology has regularly published lists of apps by different developers found violating users’ rights. Nine Tencent apps have been named on the ministry’s lists and China’s state broadcaster said the company was “going against the industry’s corrective winds”. Tencent has found itself in the government’s crosshairs this year [2021] as antitrust regulators targeted its dealmaking and the exclusive licensing deals of its music unit. Gaming is also one of Tencent’s core businesses, but in August China imposed new restrictions on child gamers as part of a crackdown on the industry, allowing them to play for only three hours a week. The regulatory cloud dented the company’s revenue growth in the three months to September, dropping to 13 per cent from the 25 and 20 per cent recorded in the preceding two quarters. “

Tencent will do whatever it takes to regain its addictive hold on adolescent boys who become men who turn to gaming any time reality gets a bit much. Of the 720 million registered gamers in China, 110 million are children, and it is their adolescent journey of formation that establishes a lifetime of addiction.

“Cai Rongjun, a 31-year-old PhD student in Beijing, started playing video games when he was 13 and now plays Tencent’s Honor of Kings for about two hours each day and has spent Rmb2,000 on the game. “I initially played in order to socialise with classmates and friends, then after you buy skins [costumes and accessories for players’ avatars bought inside the game] and tasks, you start to get addicted to it,” he said.”

If CCP propaganda can be naturalised, as an integral aspect of socialising with friends, part of becoming an adult, the autocrat’s utopia is realised. This is way beyond what Orwell’s 1984, written 80 years ago, ever imagined.

Tencent and the CCP need each other, and will work together. Tencent has the tech, the developers, the talented code cutters, and the addicted audience. The CCP has the regulatory power to determine whether Tencent succeeds or fails, and it has the most heroic of hero stories, of China’s triumph in the face of adversity. The party’s story becomes your personal story, and you addictively replay and embellish it every time you enter the metaverse. It’s self-fulfilling.

Right now this is a ways off, but the tech to get it done is rapidly being invented, miniaturised, fine tuned. The 2021 docos are a start. Xinhua’s savvy Key Online Leader, Miao Xiaojuan, doesn’t just host the video tour of China to illustrate what a wonderful whole-process democracy China has become, she tweeted every step of the doco assembly, day by day, to her many fans. They of course performed their own likability by retweeting Xiao.

You can watch the full one-hour end result as a You Tube doco, but you can also access much shorter segments online, all framed and edited to look like those being prompted to repeat the CCP mass line are speaking directly, spontaneously, sincerely to you, the viewer.

Following the Soviet example, China’s propaganda used to signify important people by calling them personages. Ordinary folks are just persons, VIPs are personages, more than a person. That now seems so old-fashioned, a coded communist way of say8ng all animals are equal, but some are more equal than others.

These days not many leaders are labelled as personages, but the concept of being more than a person has a new incarnation: the Key Online Leader.

Right now the party-state may be cutting down to size many celebs, film stars, influencers; all the better to discipline them to perform the mass line. Their performance of CCP phrases becomes the gateway to regained influence. Round and round.

Miao Xiaojuan is at the forefront of personalising propaganda, and has many imitators, for whom their face is the beginnings of fortune. They know how to emote on cue, how to embody the “positive energy” the party-state demands of everyone in the public sphere.

That’s not new. For years Xi Jinping has explicitly said the surname of all media is Party. What is newer is the emergence of actors who know how to perform themselves as infectiously likable exemplars of positive energy we are all drawn to, women and men, young and old. We buy in to not only the positive attitude the KOL displays, and we want to believe all who speak to her, and to us. Propaganda evolves.

Foreign influencers now seem amateurish by comparison.

[1] Jiarui Sun , China’s Pink Cyborg Cyber Nationalism In Meng Language, Master of Arts in Liberal Studies thesis, Dartmouth, 2019