JADED

Jade, solar, dams, expressways, power grids jostle for space at the pass

Second topic in a series predicting Tibet in 2022

Blog 1/3 on Tibet becoming a pumped hydro battery

In 2022 construction begins on Qinghai Golmud Nanshankou Pumped-storage power station to absorb solar array oversupply, according to China’s National Energy Administration. 青海格尔木南山口抽蓄电站 .

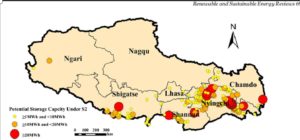

After China built its first pumped hydro system in sacred Yamdrok Yumtso, south of Lhasa, in the early 1990s, little further was heard of pumped hydro, for many years. Now, Chinese engineers are busily planning pumped hydro everywhere.

For decades there was a railway from Lanzhou and Xining out west into the most arid part of the Tibetan Plateau, stopping at the foot of the Kun Lun mountains, very much middle of nowhere, beyond the industrial hub of Gormo, which was the main destination of the railway, to enable extraction of the oil (and later, gas) discovered in the arid Tsaidam Basin.

For decades there was a railway from Lanzhou and Xining out west into the most arid part of the Tibetan Plateau, stopping at the foot of the Kun Lun mountains, very much middle of nowhere, beyond the industrial hub of Gormo, which was the main destination of the railway, to enable extraction of the oil (and later, gas) discovered in the arid Tsaidam Basin.

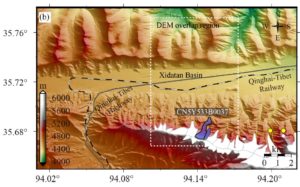

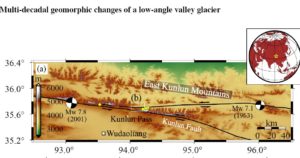

Decades later a rapidly prospering China decided to build that railway all the way to Lhasa. The biggest barrier was the Kun Lun and its parallel range, the Burhan Budai mountain chain. There was just one gap, already well known to Chinese engineers, the Nanshankou, the south mountain pass, which already was the corridor for the first highway to Lhasa, the first oil pipeline to Lhasa, then the first railway, the first optical fibre cable, the first high-voltage power grid and most recently the new expressway to Lhasa. Little wonder China proudly calls this the Qinghai-Tibet Engineering Corridor.

This pass leading up to the permafrost and glaciers of the high plateau is also the valley of a river, known to China as the Golmud He (Gormo River), so mapping the QTEC simply meant following the riverbed.

When the railway was built, and began operation in 2006, one of the proudest achievements was the ascent into the Kun Lun, with a high altitude station called Nanshankou, that featured in innumerable propaganda videos celebrating China’s conquest of nature.

PUMPED HYDRO COMES BACK TO TIBET

Now Nanshankou is to have a dam, a special kind of hydro dam, that turns Tibet into an enormous battery, able to store electricity for release as and when distant users actually want it. The Nanshankou pumped hydro dam was announced in late 2021, and work begins in 2022. Precise location: 36°11′34″N 94°46′46″E

Until now the only pumped hydro dam in Tibet is the highly contested Yamdrok Yumtso dam on a sacred lake perched above the Yarlung Tsangpo south of Lhasa. When it was built, in the 1990s, there were worldwide protests at the desecration of a lake sacred for its capacity, on its surface when ruffled by winds and passing cloud reflections, to portend where to find infant rebirths of deceased meditators. Receptive, attuned minds would sit in meditation facing the lake, and intimations would arise, triggering a search party to head in the right direction.

From an engineering point of view Yamdrok Yumtso was too good to ignore. Pumped hydro, like all hydro dams, uses gravity fall of water to turn the turbines that generate electricity. But during those hours of the day when consumer electricity demand is low, pumped hydro uses its electricity to pump water back uphill, back into the lake dam, storing it until peak demand arrives, then the water rushes down again, and peak hour is met by peak production.

At Yamdrok Yumtso that means mingling the waters of a self-contained, self-balancing lake with the chemically different waters of the Yarlung Tsangpo below; but their proximity made it, for China, an obvious project, even though Lhasa then grew so fast, on money pumped from Beijing, that this pumped hydro project quickly became too small to keep up with rising demand.

WHY DAM AN ALPINE DESERT?

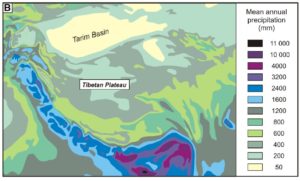

But why “the world’s largest pumped storage power station in high-altitude areas”, as China calls it, at Nanshankou? This is one of the driest parts of the Tibetan Plateau, and the little rain falling on the Kun Lun range remains in the glaciers.[1] It is close to the most industrialised district, which has its own electricity supplied by burning the coal, oil and gas extracted from under the Tsaidam Basin. The river doesn’t flow all year, and peters out in alluvial fans into the desert sands. Hardly the obvious location for the world’s largest pumped storage power station in high-altitude areas.

The reason is that China’s Huawei has built its biggest solar power array nearby, and much of the electricity generated by this showcase project is wasted, both because other provinces stick by their provincial champions, usually coal burning power stations, and because in the daily cycle, power is generated at times demand is low.

So Tibet, already made to work for China in so many ways, is to also become a battery storing solar energy behind a dam wall, to be released back downhill in peak demand hours.

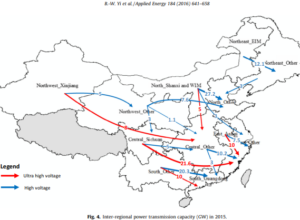

China built its solar farm on such a massive scale, in such a remote area, for two reasons. First, there is a lot of sunshine in arid areas, seldom interrupted by clouds, in both winter and summer. Second, because China has built nine big, standard hydro dams on the Yellow River in Amdo, there are power grids in place capable of transmitting electricity to far distant provinces of inland China, perhaps even to the coast.

The one thing missing is a battery. No lithium battery, no matter how big, can store anything like the energy pent up within a high altitude dam wall. Although the Tsaidam Basin is a prime source of lithium for making batteries, a pumped hydro dam is much cheaper and much bigger.

China has declared this dam the biggest pumped hydro at high altitude, a prize category not yet invented by the Guinness Book of Records, a book China loves. Maybe they could be persuaded?

However the river to be dammed has been re-engineered by all those highways., expressways, railways, pipelines, optic fibre cable and power grids all crammed into this one valley. So how big is it? Maximum electricity generating capacity is planned to be 2400 megawatts. By comparison the installed capacity of the Yamdrok Yumtso dam is 112 megawatts.

China has discovered a new way the landscape of Tibet can serve distant Chinese needs.

WILL THIS DAM EVER HAPPEN?

However, while Tibetan voices are silenced, there are plenty of powerful Chinese voices that might put a stop to the planned Nanshankou pumped storage hydro battery.

This is because that gap in the mountains that China calls Nanshankou is the gap utilised by the power grids, expressways, railway, pipelines and other infrastructure China collectively names proudly as the Qinghai-Tibet Engineering Corridor. They all jostle for space on the valley floor, with its gentle gradient, that has for decades been China’s gateway to the high plateau.

Are all these services to be displaced, dislocated to make way for a giant dam that rises and falls daily, even hourly, according to electricity demand thousands of kms away?

The newly built expressway will have to take a different route to accommodate the impounded water?

The single rail line to Lhasa, which can handle only gentle gradients, will have to relocate?

DOUBTS, OBSTACLES, CONSTRAINTS

China’s National Energy Administration has political power, in a time when China is under global pressure to reduce coal consumption and increase solar and wind energy. But the bureaucracies and ministries that build roads, railways, pipelines, and power grids also have powerful patrons and networks.

Then there are the natural obstacles, in a land prone to massive earthquakes that then trigger glaciers collapsing into ice avalanches. Hardly a landscape for a hydro dam.

A further complication is proximity to the sources of both the Yellow and Yangtze rivers, now designated as sacred wildernesses to be preserved for all time behind red lines, for downstream benefit.

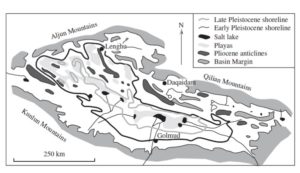

Then there’s the other end of this river, trickling into desert sands, forming a large badland playa and a salt lake from which China mines most of its potash fertiliser. Now that climate change has caused rainfall to rise, threatening Golmud city with waterlogging, what effect will an on/off hydro dam upstream have on river flows and the industries accumulating wealth by extracting and processing the salts of the Qarhan lake, where this river system ends?

On the northern far side of the playa relentless winds deposit fine sand, piling it up into an advancing wall, preventing any further flow of this glacial river that disappears into the sands. For today’s new era China, insistent on becoming a space power, these sands bring to mind the surface of Mars, which one day Chinese taikonauts/cosmonauts/astronauts may visit, so simulating Mars is now a glamour campaign industry, as worlds old and new collide. Marx goes to Mars via Tibet.

JADE, MOUNTAINS OF TIBETAN JADE

Then there’s the jade, the famous pure white nephrite jade of the nearby peaks, source of most of China’s jade, valued so highly it was inlaid into all the medals awarded at the 2008 Beijing Olympics. That was peak year for Nanshankou, the year it lived up to the promise in its Chinese name, which literally means south mountain pass.

To Tibetans this descent from the high plateau down to the Tsaidam Basin is the north face of the mountains defining the northern Tibetan border with Xinjiang, a double north. So how come China calls it a south gate?

It is south of Gormo (Golmud in Chinese), a last outpost of Chinese state reach, halting at the great climb. It is where, for several decades, the railway extending China’s reach deep into the arid interior, came to a halt. The Nanshankou hinted at treasure beyond China’s reach, treasure which could fulfil the hopes of lowland China, that beyond is a treasure house of the west, a Xizang, as China calls Tibet.

It is south of Gormo (Golmud in Chinese), a last outpost of Chinese state reach, halting at the great climb. It is where, for several decades, the railway extending China’s reach deep into the arid interior, came to a halt. The Nanshankou hinted at treasure beyond China’s reach, treasure which could fulfil the hopes of lowland China, that beyond is a treasure house of the west, a Xizang, as China calls Tibet.

However, when the pure white jade of Nanshankou was discovered, in 1992, it didn’t trigger anything like the awe and brand reputation it has enjoyed since 2008. Jade, like gold and gemstones, holds its value through scarcity. The last thing the super-rich need is Tibetan mountains of the stuff, sticking out, shining in the sun, available by the truckload.

Little more than a generation ago, 1992 was a different world on the far frontier, where China’s state was barely present, and rapacious greed ruled. In this lawless land beyond the frontier gangs of Chinese Muslim hunters shot and killed Tibetan chiru antelopes by the thousands, for a handful of underbelly fur that could be spun into shahtoosh, the lightest of all shawls. State power did almost nothing to curb the slaughter.

Chinese gold seekers swarmed the often dry riverbeds seeking flecks of gold, in the hope of making fortunes. Again, state power seldom extended that far into the arid lands of Amdo. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, predatory extraction was common, with Tibetans almost powerless to enforce Chinese laws designed to prevent plunder.

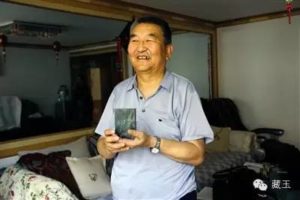

In 1992, Tashi, an official in the Golmud city administration, escaped the bureaucratic humdrum, with his kids, to go exploring in the mountains towering above his drab industrial town. In a story told and retold in official media, the jade he and his boys found, was not flecks and pebbles but shining peaks of hard nephrite, plentiful beyond belief.

Although this story is often told, it is not clear whether town secretary Tashi is Mongol or Tibetan. Mongol influence in northern Tibet for many centuries was strong, and to this day most place names on the maps are Mongolian. This cold and arid land was very much where Mongol ad Tibetan cultures mingled; then separated by the conquests of the Qing dynasty. When Tibetan lamas made the long journey from Lhasa to Beijing, to bless the emperor, this was on their route, perhaps the most arduous portion, without villages, fresh supplies, only the intense cold of the Kun Lun mountains. In 1904 the 13th Dalai Lama prudently retreated from the invading British. This is the way he came, long predating the QTEC Qinghai-Tibet Engineering Corridor.

” A route of merchants, ambassadors, taken by princes and Dalai Lamas, the Xining–Lhasa route seems to have played, then, a role as important as that of Lhasa–Kathmandu. Today the trip is made in five days by car. Until 1955, it was a journey of three to four and a half months, on horseback for the men, on the backs of camels and yaks for the goods (camels only between Xining and Nakchu). It was, by the old route, a little more than 2,100 kilometres and it was necessary to cross a desolate windy plateau and the Tangla pass at 5,200 meters. What did one buy, what did one sell in Xining? The Tibetan products: gold, musk, furs, woollen cloth, wool, stag horns, medicinal plants, leathers and skins; products coming from overseas via Nepal and Lhasa, like coral and amber, conches, gems. Chinese products: tea, silks, porcelains, which China exported everywhere in the world; agricultural implements, domestic tools and utensils, food products, cloth, paper; and a lot of silver in ingots.”[2]

TIBET’S FIRST EXTRACTIVE INDUSTRIES ZONE

In 1992 Gormo was an ugly, almost treeless industrial town at the farthest edge of Chinese power. Oil had been discovered, and a railway track was built a few years earlier, to haul crude oil in tanker wagons off to refineries in Lanzhou. The other major industry was scooping up the salts from the flat dry lake beds, especially Qarhan (Charhan Tsaka in Tibetan) just to the west of Gormo/Golmud. Of the many briny lakes of the Tsaidam basin, Qarhan was the quickest to become an extractive enclave, because the salts were high in potassium, essential to manufacturing chemical fertiliser providing the key ingredients of nitrogen phosphorous and potassium (NPK), at a time when revolutionary China turned away from the traditional practice of fertilising the fields with collected human wastes.

Gormo/Golmud, although at the heart of Haixi/Tsonub Tibetan and Mongolian Autonomous Prefecture had special status as a city, exempting it from any requirement that specific nationalities had special rights. It was open to all who came to seek their fortune. Municipalisation of formerly “autonomous” counties and prefectures later became a main official strategy for undoing legal autonomy, across Tibet.

TREASURE HOUSE OF THE WEST

Even before Tibet was fully conquered by the Peoples Liberation Army, Qarhan was discovered to be a treasure house: “Between 1955 and 1956 a series of major new general surveys were carried out on the Qaidam Basin. They described the Qarhan Playa as “a giant salt storehouse” and indicated that ‘its salt bed has a [potassium] K content of 0.40% and it is estimated that the K content may reach 10% or more.’”[3] The landscapes of Tibet became capital, ready for monetisation.

Lithium salts were also present in the lakes, but of little value prior to the electric vehicle boom. Natural gas was later discovered in the Tsaidam, and exploited, but in 1992, Gormo was literally the end of the line, a largely male emigrant Chinese outpost of raw materials extraction for the benefit of inland Chinese industries.

GREAT REVEAL, GREAT ANTI-CLIMAX

International tourists on the way to Lhasa had to stop in Gormo, to switch from train to bus, but stayed as little as possible: everything about Gormo was the antithesis of the Tibet they had come for. Tourists hoping to find Shangri-la weren’t the only ones wanting to get out of town. Municipal Secretary Daxi/Darcy/Tashi, one of few Tibetans or Mongols with access to a four-wheel drive vehicle, spent as much time as he could exploring the mountains to the south:

“In February 1992, it was the fifth day of the Lunar New Year. The 45-year-old Darcy [Tashi] took his 14-year-old son Xuhui along the turquoise jade fragments and climbed up a high mountain in Wanbaogou. Darcy and Xuhui were shocked immediately. Blocks of house-sized jade stones were exposed on the top of the mountain, exuding a dazzling light under the invisible sunlight, as if they were in the fairyland of Kunlun mythology—a place that has been silent for hundreds of millions of years in the majestic and mysterious Kunlun Mountains.[4] Kunlun beautiful jade finally came to light….. An accident deepened Darcy’s belief in finding a jade mine. When Darcy was drinking with a Mongolian hunter, he smashed a beer bottle. The Mongolian hunter said that he had seen a stone like a shard of a beer bottle on the local ‘Saw Harbuha’ mountain. It was very beautiful…… After they got out of the jeep, they suddenly found it was like beer bottle fragments. The jade blocks sparsely flowed down from the top of the mountain. The four of them climbed up to the top of the mountain without saying a word. The strange scenery of Kunlun was overwhelming, and they could not breathe: The mountains were full of exposed jade, like small houses, shades of green, exuding strangeness in the colourful light of the sun.”

That’s the official story, as told by China National Radio in 2014, repeated in many media.

Tashi, the treasure revealer, made his miraculous discovery known, but China’s jade world, which was based on scarcity, was not at all ready for jade the size of houses. A rush followed, but prices plummeted. Thousands of tons of jade a year were hacked from the peaks. Money could be made, enough to encourage plunder, while the state showed little interest.

WILD WEST TIBET

“One year after Darcy discovered Kunlun jade, the news spread like wildfire. In 1994, there was a looting incident. Afterwards, the Kunlun jade mine was contracted to individuals. Driven by the expiration of the mining rights, the Kunlun jade mine has been exploited for many years, and people of insight cannot help but sigh. Kunlun jade was not paid attention to in the first few years when it was discovered. A kilogram of Kunlun jade was only ten or twenty yuan. Moreover, the most precious white belt jade Kunlun jade was originally treated according to the standard of [Xinjiang] Hetian jade , and the green colour was regarded as a flaw. Many white belt jade materials were discarded after the white jade was cut off.”

1992 was the year Deng Xiaoping announced “to get rich is glorious”, giving permission for pillage, with the regulatory state standing back. As with the slaughter of the chiru antelopes nearby, and the gold rushes, it was a free for all. Tibet was a wild west.

“Some stories about the loss of huge wealth have spread, such as someone who paid 50,000 yuan for a carload of Kunlun jade. But one story is true. The first two wagons of high-quality Kunlun jade materials shipped to other places were not recognized by people. After they were shipped to Henan, they were told that it was not real jade, and there was no way to transport them back. Berserk. The wealth legend itself is like this, and the lifelong regrets of some people have also become an opportunity for some people to become rich.”

Did Tibetans benefit from this bonanza of Tibetan jade? No sign of it. Even Gormo municipal secretary Tashi says he never received any reward.

TIBETAN JADE GRACES THE BEIJING OLYMPICS

The turning point came only in 2007, as China prepared for the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, with all medals to be inlaid with jade, white jade for the gold medals, a bluish white for the silver, and a darker green for the bronze. Initially, the plan was to use the more famous Hetian jade found much further west in the Kun Lun mountains, in southern Xinjiang. But the Beijing Olympics Committee didn’t want to pay market rates, as China National Radio explains in detail.

Qinghai saw its moment had come, and offered to provide for free all the jade required. Qinghai Kunlun jade had at last arrived, a classic win-win. That Qinghai matters to China needed proof.

“Since the Beijing Olympics, the price of Kunlun jade has skyrocketed. In the past, the lesser Kunlun jade only cost tens of yuan per kilogram, and the better one was hundreds of thousands of yuan. Since it was determined that all Kunlun jade medals were used in the Beijing Olympics, within a short period of time, the market value of Kunlun jade has doubled.”

Now the inevitable has happened. In Xining there is a 青海省西宁市城北区生物科技产业园经三路32号昆仑玉文化博物馆事情经过 Kunlun Jade Museum, which hustles tourists to buy, buy, buy the famous Kunlun jade, the bus driver refuses to leave until his sales commission target is met.

This is not the orderly expansion of capital the CCP wants. The 2014 China National Radio report concludes: ”Mining costs are low and management is disorderly. Qinghai nephrite is produced close to the Qinghai-Tibet border, with convenient transportation. Therefore, the mining cost is much lower than the jade mining area in Xinjiang. In addition, the business order is chaotic, resources are not properly adjusted and allocated, and the mining speed is too fast. The dumping of raw materials at low prices and the fact that most of the products are shoddy have affected the reputation of the Qinghai white jade market. According to news reports, the land and resources department of Golmud City, Qinghai Province actually auctioned off the two-year mining right of a major mine for only 130,000 yuan. This will undoubtedly cause the mine owner to carry out destructive exploitation of ’fishing by exhaustion.’”

Thousands of tons of Kunlun jade are extracted each year, a huge amount even in a huge market. Yet again, Tibet serves Chinese greed.

[1] Henrik Rother, Georg Stauch, David Loibl, Frank Lehmkuhl And Stewart P. H. T. Freeman ,Late Pleistocene glaciations at Lake Donggi Cona, eastern Kunlun Shan (NE Tibet): early maxima and a diminishing trend of glaciation during the last glacial cycle, Boreas, 46 3, 2017

[2] Luce Boulnois, Gold, Wool, and Musk: Trade in Lhasa in the Seventeenth Century, in The Tibetan History reader, Gray Tuttle ed, Columbia, 2013, 479

[3] Zheng Mianping, An Introduction to Saline Lakes on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, Kluwer Academic, 1997, 3

[4] FENG Xiao-yan, ZHANG Bei-li (National Gemstone Testing Center), Study on Compositions and Texture Characteristics of Nephrite from Qinghai Province, Jnl of Gems & Gemmology vol 6 no 4 2004 7-9

ZHOU Zheng-yu,LIAO Zong-ting,CHEN Ying,LI Yu-jia,MA Ting-ting, Petrological and Mineralogical Characteristics of Qinghai Nephrite, 岩矿测试 Rock and Mineral Analysis. 2008(01) 17-20