……….AND INTO THE PASS

Blog 2/3 on Tibet becoming a pumped hydro battery

Let’s begin again.

There’s a lot to unpack. What started as a straightforward proposition to enhance China’s big investments in solar power with an upriver battery dam, turns out to have many pushes and pulls:

- climate change,

- glacial peaks,

- a jade boom in the mountains,

- earthquakes and ice avalanches,

- engineering corridors,

- petrochemical industrial hubs,

- potash salt extraction from the lake the river drains into,

- and sand piled by the wind, resembling Mars. Through it all runs a river system that, over time, largely created the Nanshankou gap in the mountains that enables China to look upward and reimagine a Tibetan Plateau landscape-cum-battery.

To unpack these many uses China has found for remote Tibetan landscapes, let’s follow the Golmud River, as China calls it, all the way from its glacier origins down to the Tsaidam Basin desert far below.

The mountains China calls the Kun Lun is in Tibetan the Tangla Riwo (not to be confused with the Nyenchen Tangla range much further south). It’s an old name, long predating the Mongol period, or, a thousand years earlier, the arrival of Buddhism.

“When Buddhism entered Tibet, it did not attempt to suppress belief in the indigenous forces. Rather, it incorporated them into its worldview, making them protectors of the dharma who were converted by tantric adepts like Padmasambhava, and who now watch over Buddhism and fight against its enemies. An example is Tangla, a god associated with the Tangla mountains, who was convinced to become a Buddhist by Padmasambhava and now guards his area against forces inimical to the dharma. The most powerful deities are often considered to be manifestations of buddhas, bodhisattvas, dakiniıs, and so on, but the mundane spirits are merely worldly powers, who have demonic natures that have been tempered by Buddhism. Although their conversion has ameliorated the worst of their fierceness, they are still demons who must be kept in check by shamanistic rituals and the efforts of Buddhist adepts.”[1]

BETWEEN WORLDS

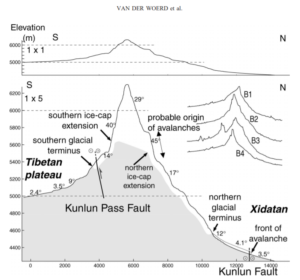

Tangla/Kun Lun is 5200m high, at the pass, with the peaks a further 1000m above. In mountainous lands, the pass is always a transition from one world to another, as the traveller reaches the saddle between higher peaks on either side. Tibetans traditionally pause at the pass –la in Tibetan- to throw small paper lungta wind horse squares to the wind, yelling “Victory to the gods!”. The liminality of the pass is usually marked by stone cairns, to which the traveller often adds a fresh stone, and marked by displays of cloth wind horse flags strung from a central pole. These honour the local gods of place, give thanks for completing the ascent, a brief pause before the descent. Tibet, the land surrounded by mountains, has probably thousands of such passes.

The Tangla Ri La (Tangla mountain pass) is more evidently a transition from one world to another than most. On either side of the pass are the towering glacial peaks recently found to abound in jade stone. At 5200 m nonTibetans struggle to get enough oxygen from the thin air into their lungs. For Tibetans making the long journey to Mongolia or Beijing, it was the highest, coldest and bleakest of passes. Then a descent of 2000 m, down to the arid badlands of innermost Asia, into the Tsaidam Basin, usually by camel or horseback, a flat land of dry salt lakes, no feed for the animals.

TIBET’S NEWEST MOUNTAINS

These mountains of the northern frontier were the last to rise above the high plateau, their orogeny pushed upwards by the same ceaseless tectonic movements that uplifted the entire plateau and its surrounding mountains. According to Chinese scientists the Kun Lun range emerged only 900 to 1000 thousand years ago, at the start (not coincidentally) of the great ice age.

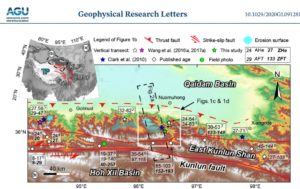

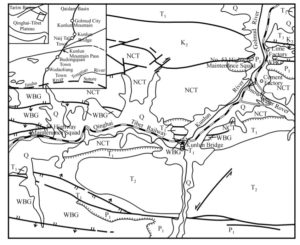

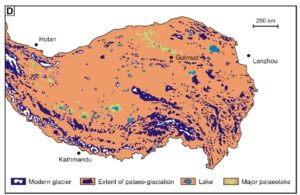

What arose above the high plateau was actually two parallel mountain ranges, shown on most maps as the Kun Lun and Burhan Budai ranges, trending from WNW to ESE. Both ranges have gaps allowing traffic through the passes. Above, on either side, the mountains reach well over 6000 m. Their glaciers today are remnants of the ice sheet that until quite recently (in geological time) covered most of the entire Tibetan Plateau, and those remnants are now fast disappearing.[2]

As the mountains rose, they trapped the clouds drifting all the way from the Indian and Pacific oceans, in the annual monsoon cycle, building more and more ice, with permafrost freezing the ground of the passes.

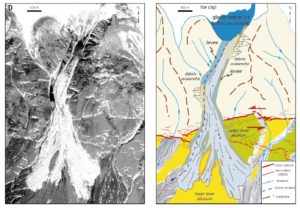

Despite a generally arid climate, and mountains holding what moisture fell, as ice, rivers existed and still exist, in fact a river system draining between the parallel ranges, one river flowing west to east, the other east to west, converging at the pass, to then flow through the gap and down to the desert below. China calls the rivers flanked on either side by mountains the Kunlun and Shuerghan rivers. Where they meet and turn north, it become the Golmud (Gormo) River, now an object of desire for the pumped hydro dam builders.

LAKES LOST, LAKES REGAINED

As elsewhere in Tibet, the more the mountains rose, the more the rivers incised ever deeper into the gaps, widening and deepening the passes. The power of water to wear away rock is universal. Yet it is remarkable in this landscape on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau’s vast flat land of lakes, just to the west, in Achen Gangyab (Hoh Xil) and the empty plain of the Chang tang, where short rivers feed into lakes, but nothing flows out. Across that enormous, almost flat, uplifted alpine desert, lakes maintain their balance through evaporation, not outflow. Magical balance. Flowing water is exceptional, occurring only in the summer monsoon. Not any longer. Now, due to climate change and increasingly wetter summers, those lakes are now expanding and overspilling.

Below, in the Tsaidam desert there once were lakes where these rivers China covets as potential batteries now flow down and down. Rivers not only drain lakes, they create new landscapes. Some of these rivers have even reversed direction of flow, Chinese scientists tell us.

MASTERING NATURE

Ongoing uplift and ongoing erosion enabled these rivers to break through the gap and flow north, down into the Tsaidam Basin, starting 150,000 years ago. To Chinese geologists, the ability of rivers to cut their own channels is “retrogressive capture”, and they warn that one day the rivers of the Kun Lun could eventually drain the Ngoring and Gyaring (Eling and Zhaling in Chinese) lakes of the uppermost Yellow River, further east, which would shorten the Yellow River. Since these lakes are now part of the Three River Source National Park, this cannot be allowed. To have those lakes disappear, after being declared national, would be an insult.

Sliding between geological and human timescales, they conclude by proposing “Therefore, it is necessary to carry out the western construction of the South-North Water Transportation Project.” That would dam, divert and pump water through canals and tunnels, from the uppermost Yangtze to the uppermost Yellow, an enormously expensive human intervention still on the list of projects, but with little official enthusiasm for funding and building it.

The need for human intervention comes readily to China’s geologists, this 2000 proposal now becoming a 2022 plan, next river along, to make the Golmud River a battery.

To geologists these evolving landscapes are changing fast. No-one knows how long it could take before energetic rivers cut upstream and drain those lakes. It could happen in 10,000 years from now, or 100,000, no-one knows. Either way, in geologic time, it’s a blink of the eye.

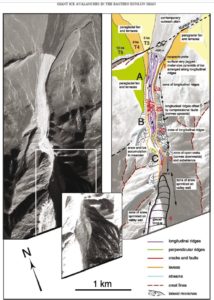

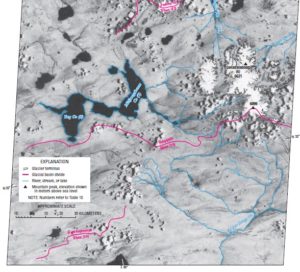

EARTHQUAKES AND AVALANCHES OF ICE

Despite these habitual impulses to add Chinese characteristics to Tibetan landscapes, the combination of recent geological uplift and climate change is hazardous. Tectonic uplift continues, and massive earthquakes of magnitude 8 occur in these mountains, causing avalanches of ice shaken from the glaciers, crashing far below at speeds up to 35 metres per second. An earthquake in 2001 immediately caused six separate ice avalanches, and a team of Chinese, French and American scientists concluded that: “such phenomena may become more common in the future as a consequence of increased glacier and slope instability caused by human induced climate change. Ice avalanches, therefore, likely constitute a significant geologic hazard in the near future.” [3]

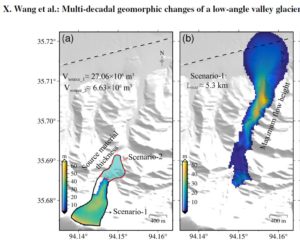

The most recent assessment, by Chinese scientists in 2021, using 1970s data gathered by US spy satellites, is similarly concerned about glacial “detachment” which could suddenly crash onto the single rail line on the route to Lhasa. Their conclusion: “The assessments show that the avalanche of the whole glacier would easily travel a distance that would threaten the safety of the railway. The increase in meltwater in summer caused by climate warming could increase the overload of the glacier surface and the supply of liquid water into the sliding surface, thus further promoting the downward movement of the glacier. The cold glacier front, the particular local topography, and long-term climate change in the East Kunlun Mountains are the main factors controlling the dynamics of the KLP-37 glacier tongue. With the warming and wetting trend of the regional climate, the risk of detachment of the KLP-37 glacier tongue may threaten the safety of the nearby Qinghai–Tibet railway and highway.”[4]

Would a heavy hydro dam add to that risk? No-one knows. There is plenty of evidence that the weight of hydro dams, and the lubricating seepage of water filtering into rock can trigger earthquakes. The case for the Nanshankou pumped hydro dam battery is far from clear.

OBJECT OF SCIENTIFIC CURIOSITY AND SPY SATELLITE SURVEILLANCE

Chinese scientists are fascinated by Tibetan landscapes as natural laboratories, especially in arid areas with little vegetation to complicate the story, and an important industry -potash fertiliser extraction- at stake where the river runs out into the salt pan. Running such experiments backwards in time is much easier when the Americans generously grant access to 1970s spy satellite data, which creates a 50 year timespan to show how Tibetan glaciers, like everything Anthropocene, are speeding up. They now downslide downslope at alarming rates, creating the danger of sudden collapse, las happened to the Aru glacier recently, not far away, on the north slope of Amnye Machen.

Even when not diverted for industrial and urban use, this river, after a noble start amid glaciers, trickles out to an ignominious, inconclusive end, soaking into the cracked plays it created, disappearing into the sands. This is the Charhan Tsaka/ Qarhan salt lake, actually the remnants of a much bigger lake that once held much water.

[1] John Powers, Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism (2nd ed), Snow Lion, 2007, 499

[2] Remco J. de Kok, Philip D. A. Kraaijenbrink, Obbe A. Tuinenburg, Pleun N. J. Bonekamp, and

WalterW. Immerzeel, Towards understanding the pattern of glacier mass balances in High Mountain Asia using regional climatic modelling, The Cryosphere, 14, 3215–3234, 2020

[3] Jerome van der Woerd, Lewis A. Owen, Paul Tapponnier, Xu Xiwei et al., Giant M8 earthquake-triggered ice avalanches in the eastern Kunlun Shan, northern Tibet: Characteristics, nature and dynamics, Geological Society of America Bulletin, March/April 2004; v. 116; no. 3/4; p. 394–406

[4] Xiaowen Wang, Lin Liu et al., Multi-decadal geomorphic changes of a low-angle valley glacier in the East Kunlun Mountains: remote sensing observations and detachment hazard assessment, Natural Hazards & Earth System Sciences, 21, 2791–2810, 2021

Hang Cui, Guangchao Cao, Badingquiying [Palden Tsewang?] Climates since late quaternary glacier advances: Glacier-climate modeling in the Kunlun Pass area, Burhan Budai Shan, northeastern Tibetan Plateau, Quaternary International 553 (2020) 53–59