TIBET’S UNIQUE WILDLIFE ENRICHES CHINA’S UNIQUENESS

Blog two of three updating Achen Gangyab/Hoh Xil: problematic UNESCO World Heritage

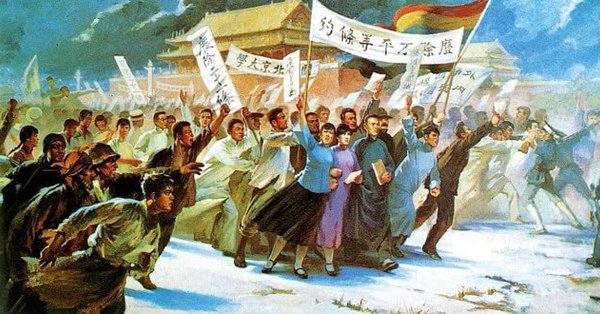

China embraced science a century ago, as the way out of China’s weakness and vulnerability.

Now China is strong, and more convinced than ever that science is the key. All aspects of life must have “Chinese characteristics”, and that includes science, which even now refuses the idea that the Han, like all other peoples, migrated out of Africa, spreading across the planet. A century of archaeology in China was driven by an insistence on Han uniqueness, that the Han Chinese originated in China, in the floodplain of the Yellow River. So when the Han honour the animals of Hoh Xil, it is a unique race of humans embracing the unique owners of Hoh Xil; the Han protagonists of human social evolution honouring the noble mammals of Hoh Xil as fellow protagonists.

Han uniqueness, as scientific fact, was invented by Li Chi, China’s first archaeologist, in the 1920s: “Whereas revolutionaries had earlier coupled literate civilization with the Han, the new science of archaeology enabled the search for continuity to move beyond textual histories into material remains. Therefore when Li and the state appropriated and mobilized vestiges of the Shang for a national narrative it was to compose the biography of the Han; contemporary minorities could only claim connections to the barbarians who surrounded Shang civilization. It is no coincidence that Anyang lies in the valley of the Yellow River—just as the Central Plains represented the geographical heart of China, so Han remained the human focus of Li’s work. His excavation at Anyang not only established the Shang as Han progenitors, it also allowed elites to push Han origins backward into prehistoric times, to the Yangshao and Longshan civilizations and even to Peking Man. This discrete, linear descent group constituted what Li called the “Chinese race,” beginning with native hominids that evolved in the Central Plains to become China’s great civilization. The advent of archaeology thus replaced the popular but questionable belief in a Yellow Emperor as Han progenitor with more scientifically plausible, but no less nationalistic, origins.”[1]

HOW TO GOVERN HOH XIL?

Qinghai Scitech Weekly’s hymn to the flagship species of Hoh Xil surely is the climax; but no, the Hoh Xil stories keep coming if we turn the page, and yet another perspective opens up. Now we see the practicalities of governing Hoh Xil, for wildlife conservation, through the eyes of those who manage this World Heritage property day by day.

Suddenly the glorious fusion of the Han race and the awesome animals of Hoh Xil becomes messy, complex, confusing, indeterminate, an agony of managerial choices imposed by circumstances, and China’s decision to be in charge.

“Reporter: How to deal with the relationship between the development and protection of Hoh Xil? Lian Xinming (Associate Research Fellow, Northwest Plateau Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences): Protection and development and utilization should be combined. Absolute protection is unrealistic. First, the investment is too large. Second, the population of protected species is rapidly expanded, which will cause instability in the ecosystem. It’s like a rodent on the grassland. It’s not right to kill the rats. How can the animals survive? The ecosystem has a self-regulating process. Similarly, mapping to wildlife conservation, blindly protecting, the number of wild animals growing too fast, the destruction of the grassland will be more and more, especially in the place of Hoh Xil, once the turf is destroyed, it is very difficult to recover.”

Suddenly, we must find a balance between protection, development and utilisation of the resources of Hoh Xil. We must worry about a population explosion among protected species. How many is too many? How to balance biomass and biodiversity? The questions proliferate, and answers are hard to find. Why? Because so little is known, in ways admissible as scientific.

Understandably, it is the scientists doing the actual research on animal populations who know best that they know little. This is more than the usual request by researchers for more research and more research finance. In the absence of the Tibetan nomads, in their removal and silencing, in the loss of generations of herders walking their yaks, sheep and goats into the Hoh Xil summer pastures alongside the migrating antelopes and gazelles, who knows anything much?

Central leaders have long insisted that removal of the nomads is the essential step required to grow more grass, and that emptied landscapes will naturally repair degradation, with no further human intervention required. But the scientists on the ground have more questions than answers, and are discovering that China’s dominion over the animals of Hoh Xil makes for agonising over management decisions, in the absence of much data. Far from being a simple triumph of anthropomorphised animal icons embraced as treasures of new era China, actual management is full of tensions, contradictions and above all, unknowns.

THOSE UNKNOWN UNKNOWNS

At last, we are done with Qinghai Scitech News on Hoh Xil. Why spend so much time on an obscure weekly for science nerds in a remote inland province of China?

Our rollercoaster ride leaves a lot of questions unanswered. How come there are so many ways of looking at Hoh Xil, all pulling in different directions? Is this collection a rehearsal for the emergence of an official line? Which of the competing narratives of Hoh Xil will emerge as China’s master narrative, repeated in official propaganda throughout China, and beyond? Has the love of animals triumphed, and we can now all relax? How hard is it to be in charge of nature? How to let pristine nature just be natural? Why are the Chinese conservation scientists on the ground in Hoh Xil worried about an unsustainable population explosion of Tibetan antelopes and gazelles? Could that happen? Could it mean, at worst, they actually have to start shooting animals to keep wild herds from destroying the grasslands? Could the removal of Tibetan drogpa nomads, and their herds, from Hoh Xil, have anything to do with the scientists’ fears of a new imbalance? Is China’s takeover of Achen Gangyab an end, or a messy beginning?

Trying to find answers is where it gets interesting. The diversity of views is revealing. China doesn’t quite know what to make of Hoh Xil. The overall tone is a simplistic, reductive, triumphal love of iconic wild animals, an embrace of the wild, so what next? Does this mean Hoh Xil is to be admired from afar, through words, docos, and glossy spreads in China National Geographic; or does it mean mass tourism? Clearly the scientists are worried that a swarm of tourists with cameras could be as destructive as hunters with guns. Yet the tourism potential is obvious, since China’s railway and highway to Lhasa slice right through Hoh Xil, forcing the migrating antelopes and gazelles to navigate across them.

Will the temptation to monetise China’s discovery of cute animals prevail? Could this be the start of a Chinese safari tourism industry, comparable to touring South Africa’s Kruger Park? China has other UNESCO World Heritage sites in Tibet –Dzitsa Degu/Jiuzhaigou for example- overrun by millions of tourists a year.

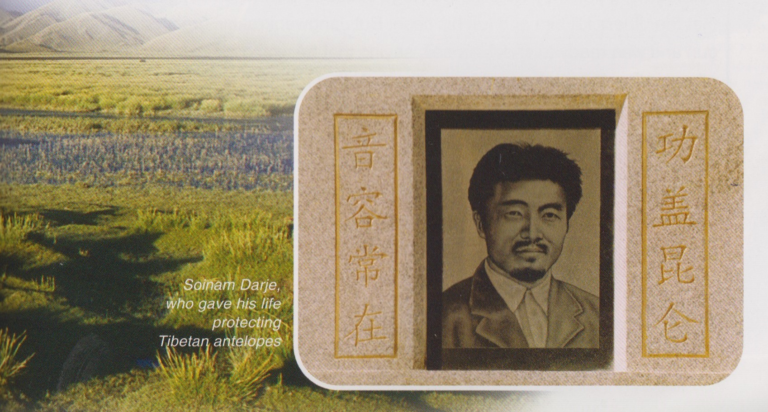

So the nationalisation of Hoh Xil and the introduction of its lovable wild animals to the mass market is not the happy ending, but a new beginning. Now the protected area managers face new responsibilities, facing up to the shocks of the recent past, when China cared naught about this remote alpine desert, letting rapacious gold diggers and vicious hunters run rampant. They juggle the erasure of Tibetan stewardship, while enshrining one lone Tibetan, Sonam Dargye, as a Chinese martyr who died to save those iconic antelopes. The history of Tibetans patrolling Hoh Xil in the 1980s and 1990s, confronting the hunters, confiscating their hauls of antelope down, is erased, yet their leader is now a red hero, his name pinyinised in a dozen different ways, one man who stood up to gangs of human predators. The contradictions keep coming.

RESTORING NATURAL BALANCE

If the past is problematic, even more so the future. The displacement of the Tibetan nomads, who used to take their herds into Hoh Xil each summer, means the clearance of grazers and herders, and no more their grazing pressure on the summer herbage. In their absence, the number of Tibetan antelopes and gazelles is rising rapidly, after so much slaughter, but where is the point of equilibrium? If there are no longer any yaks or goats eating alongside the antelopes, China’s conservation scientists have reason to worry the protected antelopes will not only recover but become too big for the summer pastures to sustain them. Underlying this fear is a huge absence of data, a bypassing of drogpa knowledge, and a growing recognition that from year to year the climate is very variable in this farthest tail end of the reach of the Indian and East Asian monsoons. 2018 was an uncommonly wet year. What next? Does it even make sense to hypothesise equilibrium as the optimal point, in an environment so uncertain?

Science as the driver of policy is, in practice, messy anywhere worldwide, if one looks closely.[2] The dynamics of Hoh Xil are especially unknown to the scientific gaze, since scientific observations are all so recent.

Perhaps the drogpa should have a voice?

[1] Clayton D. Brown, Making The Majority: Defining Han Identity In Chinese Ethnology And Archaeology, PhD dissertation, Pittsburgh, 2008, 54-5

Li Chi, The Beginnings of Chinese Civilization, University of Washington Press, 1957, 5-11

Sigrid Schmalzer The People’s Peking Man: Popular Science and Human Identity in Twentieth Century China, University of Chicago Press, 2008.

[2] John Law, Organising Modernity: Social Ordering and Social Theory, Wiley, 1994

John Law, After Method, Mess in Social Science Research by John Law, Routledge, 2004