WHAT TO EXPECT IN 2023: Blog one in a series on the year ahead

TIBETAN PLATEAU ECOLOGICAL CONSERVATION LAW

Legislation that for the first time covers the entire Tibetan Plateau as a single unit is due for debate and enactment in the National People’s Congress session scheduled for 27 to 30 December 2022.

If the draft law is enacted as scheduled (it may be awaiting further redrafting), this will legislatively bring together all the provinces into which the massive Tibetan Plateau is fragmented. This could set an important precedent if it succeeds in overriding the powerful provincial governments of the balkanised plateau.

Politically, the CCP has recognised the Tibetan Plateau as one, in successive Tibetwork Forums in recent years; a reversal of the disastrous approach taken under Mao in the 1950s, of courting the aristocrats of central Tibet, while sending its bombers and Korean War battle hardened veterans to attack eastern Tibet.

Until now, that political recognition has not been followed by legislation. The new law changes all that, explicitly including all Tibetan areas of Gansu, Yunnan and Sichuan provinces, as well as the entirety of Qinghai and Tibet Autonomous Region. Even a portion of southern Xinjiang, the birthing ground of Tibet’s chiru antelopes, is explicitly included.

Prior to the NPC legislative session, the official draft legislation is explicit about establishing this new sub-national but supra-provincial entity, starting with its formal title: People’s Republic of China Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Ecological Protection Law, 中华人民共和国青藏高原生态保护法, Zhōnghuá rénmín gònghéguó qīngzàng gāoyuán shēngtài bǎohù fǎ.

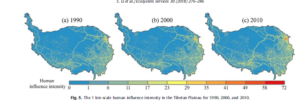

Scientifically, this makes sense. The average altitude of the plateau is 4200m, with the surrounding mountains even higher, making the Tibetan Plateau, as big as Western Europe, the planet’s great island in the sky, ecologically very different to all surrounding lands. If ever there was a case for arguing landscape ecologies transcend political boundaries, this is it. The scientists are all for it.

What does this mean in practice? Can this legislation actually override provincial governments? In today’s China, the central party-state has constant trouble trying to get provincial governments to hook into a national power grid which exports hydro-electricity from Tibet. Provincial governments instead prefer their own coal-fired power stations, which are theirs, within provincial boundaries and under their control. If Beijing struggles to activate and implement a national electricity grid, how is this ecological protection law supposed to work?

The legislation, in its Articles Four and Five is upfront about its scope: “Article 4: The state shall establish a coordination mechanism for the ecological protection of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau to provide overall guidance, Comprehensively coordinate the ecological protection work of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, and review major policies for ecological protection of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau,, major plans, and major projects, coordinate major cross-regional and cross-departmental issues, supervise, inspect and check the implementation of relevant important tasks.

The relevant departments of the State Council are responsible for the work related to the ecological protection of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau according to the division of responsibilities.

do.

“Article 5 The local people’s governments at all levels on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau shall implement the ecological protection and restoration, ecological risk prevention and control, optimization of industrial structure and layout, and are responsible for maintenance of Qinghai-Tibet plateau ecological security.

Relevant localities on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, according to local regulations and local government regulations, strengthen cooperation in planning, planning, supervision and law enforcement, and jointly promote the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau ecological protection and restoration and ecological risk prevention and control.”

Legislation at national level makes this re-unification of the Tibetan ecosystem a national task. This nationalisation was preceded by the setting up of a system of national parks that on paper provide redlined protected area status for as much as 30 per cent of the Tibetan Plateau.

But who will actually administer and enforce this newly panTibetan law? In China’s rough game of provincial bosses and fiefdoms, how much actual power will this new law be capable of exercising?

On paper, this is a partnership between central government and county governments, bypassing provinces. The initiative driving the process is vested in the State Council, which is to come up with a master plan, which is then implemented by local governments. “Article six: The State Council and local people’s governments at and above the county level on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau shall include ecological protection of the Tibetan Plateau in the national economic and social development plan.

Relevant departments of the State Council, in accordance with the division of responsibilities, organize the compilation of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Ecological Protection Plan.

“Article 8: Relevant departments of the State Council and local people’s governments at various levels shall take measures to protect the traditional ecological and cultural heritage of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and promote the excellent ecological culture of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau.”

In reality, powerful provincial governments will have little trouble in ignoring and, where necessary, overriding this law. After years of pandemic lockdowns, local government real estate investment collapse, and anaemic growth, the 2023 highest priority of provinces is in stimulating growth, and that means investing in infrastructure that damages ecosystems.

The legislation does define a role for provincial governments, in a rather vague way: “Article 12: The provincial people’s government of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau should strengthen the protection of human activities within the red line of ecological protection and regularly evaluate the effectiveness of protection. Article 13: The provincial people’s government of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau shall, according to the environment and resource utilization status, formulate ecological environment zoning management and control plan and ecological environment access.”

However, provincial governments constantly lobby central leaders for more investment in infrastructure, subsidies to industries, incentives to revitalise apartment construction, capital for agribusiness “demonstration” industrial parks, and much more. The central government, keen to stimulate sluggish growth, willingly finances the provinces to deliver. This remains an unresolved contradiction.

The crunch comes when roadbuilders, highspeed rail planners, miners, loggers and other enterprises persist in business as usual, prioritising growth over conservation. Since these enterprises are often state owned, or enjoy patronage protection of provincial power brokers, there is a direct clash of vested interests which will not be decided by citing laws.

Deep in the long text of this legislative draft are efforts to at least limit the ecological impacts of extractivism, the nation-building ideology that has governed Tibet for the past seven decades. This is where the inherent weakness of this law starts to become apparent. More on mining below.

Thus far, this legislation appears to be well-intentioned, if hard to implement in practice, even admirable in its recognition of the unity of the entire Tibetan Plateau.

But at this point we have to ask some troubling questions.

What are the primary consequences of this law, as written? What are its foundational assumptions? Who is most impacted by its implementation? Is this merely virtue signalling with little consequence? Or is it an assertion of the epistemic power of China’s hegemonic project of remaking the landscapes of the Tibetan Plateau into Sinicised landscapes under the scrutiny of the nation-state?

One way of starting to answer these questions is to identify the commonest words in the law. One keyword that is deployed 34 times in this law is “restoration”, 护修复, hù xiūfù, which can also be translated as “repair”. What is it that needs restoring/repairing? Tibetans, mindful of China’s long history of rapacious logging of eastern Tibetan forests from 1970s through to 1998; or the predatory slaughter of wildlife by soldiers stationed in Tibet, later by hunters; or the systematic draining of water meadows to separate land from water and increase livestock intensity; might suppose this emphasis on restoration is tacit admission of past mistakes and policy failures. However these are nowhere mentioned. Today’s China does not admit to past failures.

What is named, over and over, is the importance of excluding Tibetan pastoralists from their pastures, because they are to blame for degradation and desertification. Restoration means growing more grass, as if grazing, even light and skilful nomadic grazing strategies, automatically degrade grasslands, because herbivores eat grass. That has been official policy for decades.

Now this new law proclaims China’s intention to: “adhere to the principle of natural restoration.

Restoration is the main focus, integrated protection and restoration of mountains, rivers, forests, fields, lakes, grass, sand and ice; adhere to ecological priority, green development, overall planning and coordination, classified policy implementation, scientific prevention and control, and systematic governance.” [Article 3]

In order to achieve restoration: “Article 13: The provincial people’s government of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau shall, according to the environment and resource utilization status, formulate ecological environment zoning management and control plan and ecological environment access.”

Article 18: “Systematic protection and zoning and classification management of national parks, measures such as strengthening grazing prohibition and confinement, and strengthening degraded grasslands, wetlands, desertified land management and soil erosion prevention and control efforts, comprehensive improvement of severely degraded land. It is strictly forbidden to damage ecosystem functions or not comply with differentiated management. Various resource development and utilization activities are required by the control.”

China, at the highest level, chooses to ignore the abundant evidence, gathered by Chinese and international scientists, that degradation (by burrowing rodents) and desertification (by wind erosion intensified by climate change) are part of the natural cycle that Tibetan nomads are long adapted to. Human will is the solution to all problems, so human will, exercised by wilful nomads, must be to blame.

Embedded in the concept of restoration is an assumption that the goal is pristine landscapes with no trace left of human use, restored to original, prehuman wilderness. “The restoration of the original ecology, the implementation of comprehensive management of degraded grasslands such as black soil beaches.” [Article 21] China now asserts its national will, to restore a natural paradise, yet somehow adhering to the official slogan [Article 1] of “realizing the harmonious co-existence between man and nature.” Contradictions abound.

Contradictions pile up. Not only are the drained wetlands to be restored, and the forests to somehow regrow (without investing much human effort), but even the glaciers and the huge extent of permafrost are to be protected too. Article 33: “Relevant departments of the State Council and local people’s governments at or above the county level on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and their relevant Departments should strengthen the protection against earthquakes, ice avalanches, flash floods, landslides, landslides, debris flows, glacial lake collapse, permafrost melting, forest and grassland fires, heavy rain (snow), drought and other natural disasters.” How?

Article 35: “The government should strengthen the monitoring, early warning and systematic protection of glaciers and permafrost on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Qinghai Tibet Plateau provincial people’s governments should classify large ice cap glaciers and small-scale glaciers into ecological categories. Protect the red line, implement the closure and protection of important glaciers and snow mountains; delineate the protection range of permafrost regions, strengthen the protection of permafrost and mid-deep seasonal frozen soil areas; carry out glacial permafrost monitoring and risk assessment of the impact of thawing and degradation on regional ecosystems; strict control of permafrost.” In reality seasonal permafrost melt is advancing rapidly, primarily due to climate warming, because of China’s heavy industrialisation. As permafrost melts, frozen water sinks deeper, resulting in sinkholes and rivers running dry, their waters now deep underground. The only way strengthening protection of permafrost would be for China to cease coal burning. Not mentioned in this law.

This is a fantasy of perfect management, perfect risk control, perfect imposition of human will, a nationalisation and Sinicization of Tibetan landscapes by a nation-state empowered by legislation to remove the Tibetan pastoralists and thus restore nature, under the vigilant gaze of the party-state.

Who will actually implement this law? Almost certainly the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, these days more empowered than before, but still weak when it comes to any clash with rent-seeking vested interests. How can it be implemented? Article 2: “Those engaged in or involved in activities related to the ecological protection of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau shall abide by this law. If there is no provision in this Law, the provisions of other relevant laws shall apply.” Not sure what that means.

At best, this is an aspirational law, a confection of noble phrases that in practice are deployed to depopulate rural Tibet even further, all in the name of glorious abstractions, an exercise of the epistemology of power that enables the powerful to define everything, and silence those who might say otherwise. Epistemic power to determine what is knowable, known and factual, while eliminating alternatives, leads to epistemic injustice. Tibetans have had 70 years of it.

******************************

Tracking China’s legislation governing Tibet is not hard, all it takes is to check in on the NPC Observer website once in a while. But for some reason the diaspora of Tibetans seldom do so. As a result, the close reading of new laws, their assumptions, boasts and silences, are seldom seen.

Fortunately this is not so with another major new law due for adoption by the National People’s Congress in the last days of December 2022. This is the Wildlife Protection Law, revised for today’s circumstances. More on this below.

We are not quite done yet with the oddities of the special law on biodiversity that applies only to Tibet. Legislation governing just Tibet is most unusual, as China’s wider agenda is that Tibet is to be assimilated into China, and one size fits all. Even more unusual -unique actually- is legislation for the entire Tibetan Plateau, embracing two entire provinces, and portions of four other provinces.

Is this an embrace of Tibet’s uniqueness? Or is it an elaborate exercise in virtue signalling, that exempts lowland China -overcrowded, over-urbanised, its panda and elephant habitats long displaced by apartment blocks- from any such ecological conservation law?

Maybe reducing debate to just two opposites is simplistic. But the enactment of this ecological conservation law comes at an odd time, immediately after China chaired the 15th COP of the UN Convention on Biodiversity (CBD), in Montreal, earlier in December 2022. China was in the chair because China was meant to play host, in Kunming, but due to the pandemic, postponed and postponed, and after two years gave up altogether, whereupon Montreal, where the CBD permanent staff are, offered to stage the CBD COP.

China remained chair, able to ensure the participation of the world’s governments, at the highest level, to get done a long overdue deal for nature that might halt the slide towards extinction.

Did China, champion of restoring Tibet, actively chair its CBD COP? No. There was no leadership from China. By the time this COP at last convened -two years later than scheduled- China had already left the room, having gotten what it wanted, namely the “Kunming Declaration” which is headlined with one of China’s favourite propaganda slogans.

At the CBD COP UN Secretary-General Guterres did his best to rekindle action. The UN reported him saying “without nature, we are nothing”, Mr. Guterres declared that humanity has, for hundreds of years “conducted a cacophony of chaos, played with instruments of destruction”. Continuing his excoriating attack, Mr. Guterres described humanity as “a weapon of mass extinction” which is “treating nature like a toilet”, and “committing suicide by proxy”, a reference to the human cost associated with the loss of nature and biodiversity.”

But China was in the room in name only, doing little from the chair to drive an ambitious agreement to save nature. For a concise insight into what the CBD COP should have achieved, written by a team of top biodiversity specialists: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-022-01953-2

This does suggest the Tibet ecological conservation legislation, on the National People’s Congress agenda only days after the CBD COP ended inconclusively, is indeed an elaborate branding exercise in asserting China’s epistemic power over Tibet.

Epistemic power must be negotiated, which means in several modes: ontological, methodological, epistemological, axiological, teleological; all of them being modes that those primitive, backward Tibetans do actually have tomes to say about. Should China ever decide to negotiate who knows what about Tibet, instead of inscribing its legislative voice from above, it will find plenty of Tibetan interlocutors ready and able to debate the ontology of the knower, and of the known.

That day, when Chinese and Tibetans negotiate as equals, able to actually hear, is a long way off. Meanwhile the Tibetan Plateau Ecological Conservation Law rolls on, imposing on Tibet a complete Chinese imaginary, and a nasty agenda of further displacing Tibetans from their home pastures.

This become clearer if we track the story of how this legislation came into being. Tracking the legislative backstory is easily done, simply by entering as a search term the name of this law, in Chinese, 中华人民共和国青藏高原生态保护法. Up pops the lengthy process of drafting, public consultations on drafts, revisions and reworkings, plus the ideological assumptions hard baked into its framing. All is revealed.

In a country as big and complex as China, draft legislation often goes through many months of consultations with powerful vested interests who seek to bend legislation in their favour. More on that when we come to the Wildlife Protection Law, on the NPC agenda along with the panTibetan ecology restoration law.

Consultation not only gives powerful players a chance to lobby, it is also a public ritual for building the brand, raising awareness, engineering a social licence, creating a constituency for an incoming law.

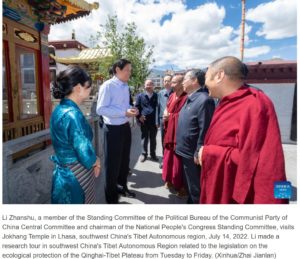

Thus it was that one of Xi Jinping’s closest factional allies, Li Zhanshu, toured central Tibet in midsummer 2022 to sell the upcoming legislation. It was one of his last public appearances, as he reached the mandatory retirement age, being 72, and as of the 20th CCP Congress October 2022 is now officially retired. His daughters, who accumulated remarkable real estate wealth during Li Zhanshu’s long stretch at Xi Jinping’s side, have reason to be grateful.

Thus it was that one of Xi Jinping’s closest factional allies, Li Zhanshu, toured central Tibet in midsummer 2022 to sell the upcoming legislation. It was one of his last public appearances, as he reached the mandatory retirement age, being 72, and as of the 20th CCP Congress October 2022 is now officially retired. His daughters, who accumulated remarkable real estate wealth during Li Zhanshu’s long stretch at Xi Jinping’s side, have reason to be grateful.

Li Zhanshu’s July 2022 visit to Shigatse, Lhasa and Nyingtri was billed as a ”research tour”, but in all official media pics the tourist is not listening, he is expounding the virtues of the new legislation. Xinhua: “Noting the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau’s special ecological status and its value to national and global ecological security, Li said the new law should embody the idea that ecological protection is the basic premise and the rigid constraint of the region’s development. It should also implement the new development philosophy, adhere to a systemic, science-based and problem-solving approach to strengthen the protection, conservation, restoration and risk prevention and control of key ecological systems, said Li.”

For cadres in Tibet, whether Han immigrants or Tibetans, this is not a welcome message. Ecosystem restoration is henceforth the rigid constraint of the region’s development. Until very recently, central Tibet was lagging, but on the same development trajectory as all of China’s 31 provinces, getting rich though industrialisation, upscaling, intensification, acceleration of production, especially the booming infrastructure construction sector, where many fortunes have been made. Now, it’s all back to nature, to implement the new development philosophy.

Li Zhanshu, in his role as supremo of the National People’s Congress, did his four day “research tour” in Shigatse, Lhasa and Nyingtri. He didn’t go to Amdo (Qinghai), where China has built heavy industry: chemical crackers, petrochemical plants, oil and gas refineries, smelters, lithium extraction, lakebed metal salts purifiers, power grids to export electricity for Tibet, lithium battery mega factories, hydro dam aquaculture agribusiness, to name a few. Not exactly suitable for ecological restoration.

Beijing is imposing a new agenda and a new post-industrial future for Tibet (except in the heavily industrialised northern half of Amdo/Qinghai). The goalposts have been moved. Little wonder the local cadres staring at the ground seem a bit underwhelmed.

Beijing is skilled in masking its operations to extend influence as listening tours. In Li Zhanshu’s four day “research tour” of central Tibet, he “held a forum to listen to the views and suggestions of the relevant parties for the legislative work.”

Who are these relevant parties deemed relevant from above, permitted to voice their concerns? They are none other than the relevant organs of party-state power. The masses are not relevant.

Who are these relevant parties deemed relevant from above, permitted to voice their concerns? They are none other than the relevant organs of party-state power. The masses are not relevant.

This becomes clearer if you look not only at Xinhua coverage of this research-tour-cum-lecture-tour in English, but at the longer report in Chinese. There Li Zhanshu directly orders the TAR cadres to fall in line with “the important instructions and requirements of General Secretary Xi Jinping on the ecological protection of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and the decision and deployment of the Party Central Committee should be translated into legal provisions. During his stay in Tibet, Li Zhanshu went to the regional people’s congresses and grassroots people’s congresses for research and talks. He stressed that the achievements made in Tibetwork and the promotion of future progress in various undertakings lie most fundamentally in the strong leadership of the Party Central Committee with Comrade Xi Jinping at its core, in the scientific guidance of Xi Jinping’s thought on socialism with Chinese characteristics in the new era, and in the uncompromising implementation of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s important remarks on Tibetwork and the Party’s strategy for governing Tibet in the new era. It is necessary to further implement the strategic thought of “ruling the country must be ruling the border, ruling the border first to stabilize Tibet“, implement the Party’s guidelines and policies on ethnic and religious work, make safeguarding the unity of the motherland and strengthening ethnic unity the focus and point of emphasis, achieve long-term peace and stability, and promote high-quality development. Long-term peace and stability are the basis and condition for promoting high-quality development. We must always guard against and combat the plots and activities of various separatist forces and resolutely safeguard national security and stability in Tibet. Tibetan people’s congresses at all levels should closely focus on the implementation of General Secretary Xi Jinping’s important instructions and requirements on Tibetan work, perform their duties in accordance with the law, take charge.”

This is a slab of standard CCP jargon, but it makes clear that this legislation springs direct from the head of Zeus/Xi Jinping and is the  legislative magic weapon that makes his word the law that rules all. China speaks of rule of law but actually means rule by law, with the law specifying who is to obey and how. From Li’s instructions, it is clear that this “ecological protection” law is totally part of the political agenda stability, unity, national security and safeguarding the frontier against plots. We have at last identified the actual agenda of “ecological protection.”

legislative magic weapon that makes his word the law that rules all. China speaks of rule of law but actually means rule by law, with the law specifying who is to obey and how. From Li’s instructions, it is clear that this “ecological protection” law is totally part of the political agenda stability, unity, national security and safeguarding the frontier against plots. We have at last identified the actual agenda of “ecological protection.”

Rule by law, misleadingly labelled as “rule of law”, is something Xi Jinping is clear about, including “the Party’s leadership over law-based governance.”[1]

Does an ecological restoration law mean there is to be no more mining of Tibet, even though Chinese geologists have mapped at least 40 major deposits of copper/gold/silver/molybdenum within 200 kms of Lhasa?

Not at all. The draft Tibetan Plateau Ecological Conservation Law has two articles on how mining is to be done: “Article 30: The establishment of mining and prospecting rights on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau shall conform to the national land and space planning, and mineral resource planning requirements. Those engaged in mineral resource exploration and mining activities on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, holders of prospecting rights, mining right holders should adopt advanced and applicable process equipment and products, and choose environmentally friendly and safe prospecting, exploration and mining technologies and methods to avoid or reduce damage to mineral resources and the ecological environment. Take protective measures such as avoidance, mitigation, and timely repair and reconstruction to prevent environmental pollution and ecological damage.

“Article 31: Local people’s governments at and above the county level on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau shall adapt measures to local conditions, take measures such as eliminating hidden dangers of geological disasters, land reclamation, restoration of vegetation, and prevention and control of pollution. Speed up the ecological restoration of historical mines and strengthen the monitoring of mines under construction and in operation. Urge mining rights holders to perform mine pollution prevention and ecological restoration responsibilities in accordance with the law. When exploiting mineral resources on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, scientifically formulate mineral resource exploitation plans and Ecological Restoration Program for Mining Areas. Newly built mines should be strictly in accordance with the green mine construction standards and regulations on planning design, construction and operation management. Production mines should implement green upgrades, strengthen the operation and management of tailings ponds to prevent and resolve environmental risks.”

The law does prohibit mining riverbeds for sand, for urban construction concreting. But mostly these legislative prescriptions are vague. Even if implemented seriously, the most they would achieve would be to push out small-scale, under-capitalised miners; while letting in large corporate miners with plenty of public relations website managers, whose strategy for making safe the huge tailings ponds of mine waste is to truck in fly ash from the waste pits of lowland coal fired power stations, in the hope that the mix of toxic fly ash and toxic mine waste will, at subzero temperatures, turn to concrete and thus be safe. Does this new legislation have anything to say on this? No. Mining, and China’s extractivist ideology will persist.

In the name of ecological restoration, Tibetans are further demobilised, made to stay put in new border villages, under surveillance. That’s not ecological restoration, which requires lots of hands to plant and care for grasses and saplings in areas that are degraded. Removing the customary guardians of the land, in the name of ecological restoration, is ridiculous.

China’s NGOs that used to advocate for environment and for community empowerment rather than systemic top-down disempowerment, have themselves been disempowered since 2014, early in Xi Jinping’s reign. However, there are professional biodiversity specialists still, such as the China Biodiversity Conservation and Green Development Foundation http://www.cbcgdf.org/ and they did make use of the formal legislation drafting consultation process to make a detailed submission.

In September they took up the formal invitation of the National People’s Congress inviting public comment, https://thediplomat.com/2022/02/the-chinese-legislatures-hidden-agenda/ by convening a gathering, in Beijing, of “experts, professors, representatives of public welfare organizations and volunteers from research institutes and universities.” Weeks later, they published their systematic critique on the Sohu platform, in which they politely said what silenced Tibetans cannot say, dare not utter, given the likelihood of being charged with “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” 寻衅滋事; xúnxìn zīshì, a serious crime in China.

They pointed out the muddled logic of the draft legislation: “Although the Draft provides for planning and control in a piecemeal manner, it is rather fragmented and unsystematic, and the content of key territorial spatial plans is incomplete. Therefore, it is recommended that comprehensive provisions be made for the national spatial planning, ecological protection and ecological restoration planning involved in the ecological protection and green development of the Tibetan Plateau.”

They quietly pointed out that the Tibetan Plateau includes Ladakh, the mountainous districts of Nepal and Bhutan, and Indian Himachal, Uttarakhand, Sikkim and Arunachal, so any serious effort at ecological restoration of the plateau should be an international cooperation: “the legal definition of the Tibetan Plateau itself, including its characteristics and traits, is missing. Especially since the Tibetan Plateau involves transnational boundaries, it is all the more important to provide a clear definition and declare our legal sovereignty while eliminating international disputes. The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau straddles the territories of many countries, and as an ecological region with global climate impact, it should be jointly protected by neighbouring countries. It is proposed that the Draft establishes an international coordination mechanism for the protection of the Tibetan Plateau, which will help to clarify the legal basis of the neighbouring countries around the Tibetan Plateau.”

They quietly pointed out that the Tibetan Plateau includes Ladakh, the mountainous districts of Nepal and Bhutan, and Indian Himachal, Uttarakhand, Sikkim and Arunachal, so any serious effort at ecological restoration of the plateau should be an international cooperation: “the legal definition of the Tibetan Plateau itself, including its characteristics and traits, is missing. Especially since the Tibetan Plateau involves transnational boundaries, it is all the more important to provide a clear definition and declare our legal sovereignty while eliminating international disputes. The Qinghai-Tibet Plateau straddles the territories of many countries, and as an ecological region with global climate impact, it should be jointly protected by neighbouring countries. It is proposed that the Draft establishes an international coordination mechanism for the protection of the Tibetan Plateau, which will help to clarify the legal basis of the neighbouring countries around the Tibetan Plateau.”

Unless the legislation due for adoption 27 to 30 December 2022 is changed greatly, there is no indication whatever that these modest proposals have been heeded. Perhaps this is not surprising, in today’s new era, since this elite gathering of scientists and lawyers went one step further: “Increase the role of public welfare organizations, volunteers, etc. in the Draft. To protect the Tibetan Plateau, the participation of social forces should be emphasized. It is suggested that the Draft establish provisions to encourage the participation and supervision of public welfare organizations, volunteers and other social forces, and social organizations can bring public interest litigation as the subject of civil litigation for ecological damage.”

Just imagine Tibetans suing the state for its failure to restore the ecology of the Tibetan Plateau. Inconceivable.

*****************************************

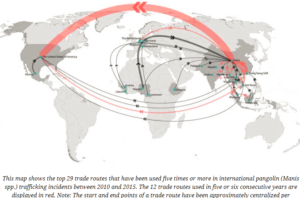

So at last we come to the other law set for debate at the National People’s Congress in the last days of December 2022: the Wildlife Protection Law, 野生动物保护法an obvious match with the Tibet Plateau ecology restoration law.

This too has had a long gestation, an even longer backstory involving China’s bad reputation as the driver of global trafficking in wildlife, and of the likely origin of the Covid virus pandemic in wildlife wet markets of Wuhan in late 2019. China has major reputation repair work to do, yet it also has a huge industry that “farms” wildlife in cages, for human consumption, and a deep heritage of using rare animal parts in traditional Chinese medicine. More recently, as China has accumulated wealth, one of the most public displays of being rich is to eat an animal killed on the spot in an expensive restaurant, the more rare, exotic and expensive the better.

At first glance, the Wildlife Protection Law puts a stop to all the trafficking in live animals and in animal parts., about time. Yet, on closer examination, during the lengthy consultation process the vested interests of the caged animal farming industry have managed to insert into this legislation clauses that exempt them from regulation, and enable this cruel industry to continue.

Fortunately, the Environment Investigation Agency, an NGO of animal lovers, has tracked the revisions to the Wildlife Protection Law as it approaches enactment: “the second revision draft has retracted the punishments of the managers of illegal operations, removed “guarding against risks” from the principles and continued to endorse the commercial utilisation of wild animals, including highly endangered species such as leopards, pangolins and tigers. Most significantly, this latest revision of the draft Wildlife Protection Law loosened the requirements for entities to hunt, capture and breed wild animals. Since 2020, the Chinese Government has also published a list of wildlife to be reclassified as livestock, a plan to roll out its special marking scheme for the trade of animals under special state protection and permission to continue the captive breeding of a range of animals, including exotic parrots for the pet trade and snakes for use in traditional Chinese medicine.”

In October 2022 EIA revealed that “In China’s latest Wildlife Protection Law revision, conservation once again gives way to exploitation. After almost two years of silence, the Chinese Government has finally released a second revision of its draft Wildlife Protection Law for public consultation. Wildlife Campaigner Ceres Kam concluded: ‘Sadly, the second draft confirmed our fears that the voices promoting the farming and use of wild animals have again won the upper hand.’”

Those two years of silence in public mask two years of intense lobbying by the wildlife trafficking industry, against a Wildlife Protection Law 野生动物保护法proposed in 2020, in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic outbreak, the corona virus widely recognised as jumping from animal to human infection caused by wildlife trafficking, despite China’s angry denials.

As is often the case, the state was at war with itself. At a national level, in the National People’s Congress, there was widespread recognition that China needed to lift its game on wildlife trafficking, hence the draft law. But at prefectural and county levels of government, the intensive and cruel “farming” of wild animals had for years been promoted as a good strategy for poor farmers to grow rich, and local governments often published business cases on how much money could be made, thus achieving Xi Jinping’s promise of “rural rejuvenation.”

So thousands of local cadres pushed back, and eventually won. Their pushback was not public. They knew the endless “zero-Covid” lockdowns did nothing to win popular support for inserting loopholes in the Wildlife Protection Law. For two years the draft law was on the NPC agenda, but never ready for final rubber stamping. Then in October 2022 the wildlife farmers, an industry that generates tens of billions of dollars in sales and employs hundreds of thousands of workers, got their exemption.

Back in early 2020, one of the law’s architects, Yang Heqing, a senior staffer of the National People’s Congress, was confident the people were all for a ban on all forms of wildlife trafficking: “The public opinion and reflection since the prevention and control of this epidemic shows that all parties generally agree with a total ban on the consumption of wild animals.” Yet, two years later, he was outmanoeuvred.

Back in early 2020, one of the law’s architects, Yang Heqing, a senior staffer of the National People’s Congress, was confident the people were all for a ban on all forms of wildlife trafficking: “The public opinion and reflection since the prevention and control of this epidemic shows that all parties generally agree with a total ban on the consumption of wild animals.” Yet, two years later, he was outmanoeuvred.

***************************************

Here we have two laws, both due for adoption in the late December 2022 NPC session, both open for extensive consultation, both attracting vigorous lobbying by elite insiders. Yet the outcomes differed. The caged wildlife farmers got their exemption from regulation; the scientists and lawyers at prestigious universities, arguing for community involvement and internationalisation of the Tibet Plateau ecological law got brushed aside, ignored.

What can Tibetan learn from this story of two laws in the making? Most obviously, the formal consultation process is in reality restricted to elite insiders, so if Tibetans want their voices heard they first need well-connected patrons.

Second, even the elite insiders, who dare to take seriously China’s claim to restore ecologies of the Tibetan Plateau, can lose if they challenge the current ideology of securitisation of everything. Peking University-based Shan Shui conservation NGO, which does understand Tibet and Tibetans, was first to realise the Wildlife Protection Law draft had changed to favour the “farmers.” They were ignored.

Third, China’s complex party-state, an apparatus with 96 million CCP members, is chronically at war with itself, and sometimes the lower levels win.

Where does this leave Tibetans, who have good reason to fear being charged with the serious crime of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” if they seek to participate directly in the open consultation phase of legislative drafting?

Tibetans have reason to speak. With the Tibetan Plateau ecology restoration law, all is not as it seems. Careful consideration reveals that ecological restoration does displace Tibetan nomads from their landscapes, but does not stop mining. Wildlife protection exempts captive breeders of wild animals from penalty, as long as they no longer sell animals to restaurants, selling only to traditional medicine makers. These laws strengthen the state, and rule by law, while letting predatory miners and predatory wildlife exploiters carry on.

China’s strong party-state exercises its epistemic power to silence Tibetans. The holder of epistemic power gets to decide who is a knower, and who is merely known. China decides it knows Tibet and Tibetans, and Tibetan voices are at best trivial or delusional, at worst criminal. Epistemic power leads to epistemic injustice,

Both of these laws went through a lengthy consultation process that allows powerful vested interests to negotiate carve outs that exempt them from onerous regulation. Did Tibetans, in any of the six provinces named in the plateau ecological restoration law, ever get to change it? Or even to speak, from Tibetan speaking positions, to it? Or were Tibetans, all seven million of them, spoken for by the legislative voice of the party-state? If a global pandemic isn’t sufficient to get a law in China to ban captive breeding of wild animals, what awaits the captive Tibetans and their captive nation?

The NPC session of 27 to 30 December 2022 may decide there must be a further round of consultations, so sanity and humanity may yet win. The Tibet Plateau ecological restoration law may remain open for comment, and these days Tibetans are increasingly aware of the laws and lofty rhetoric of their alien rulers. We live in hope.

One day, Tibetans will find ways of being heard, in the elaborate and lengthy process of NPC consultations on draft laws. Tibetans will at last be recognised as knowers of their own homeland.

31 December 2022 POSTSCRIPT:

Since this blog was published 18 December 2022, China’s National People’s Congress has met, and decided the “public consultation” process will continue until 28 Jan 2023.

The NPC did issue its own commentary to the draft Tibetan Plateau ecological restoration law, indicating it has, predictably, ignored the suggestion that this law be internationalised to include the entirety of the Tibetan Plateau. The NPC commentary on the draft does propose two specific changes to this law, which will be enacted by the NPC at one of its 2023 legislative sessions:

“Improve the public participation procedures; units and individuals have the right to report and prosecute illegal activities that pollute the environment of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau and destroy the ecology of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau.

“Clarify that any loss of livestock by wild animals predation shall be compensated according to law.”

[1] Xi Jinping, Provide Sound Legal Guarantees for Socialist Modernisation, speech at the Central Conference on Law-based governance, 16 Nov 2021; Governance of China vol 4, 329