What to expect in 2023: A series of LITHIUM, LITHIUM, LITHIUM blogs about the short term future of Tibet

#3: TIBET’S MOMENT ARRIVES

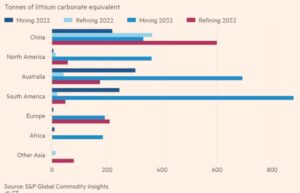

For Tibetans, 2023 Water Rabbit year is auspicious. Europe is rethinking what to make of the rise and rise of China, open to questioning complacent assumptions that held for decades, and now seem so yesterday. European countries are less and less willing to take the short-term chance that teaming up with China is a shortcut to prosperity. There is growing recognition that Europe is willing to do some heavy lifting on compensating the Global South for the impacts of climate change, while China refuses, claiming it too is a developing, not a developed country, not obliged to pay. There is rising awareness in Europe and across the richer countries that conflict minerals are out, and onshoring the local extraction and processing of critical minerals is in. Leaving the entire global manufacturing supply chain reliant on China to sell to the world from its dominance in critical minerals processing, is now understood as dangerously risky.

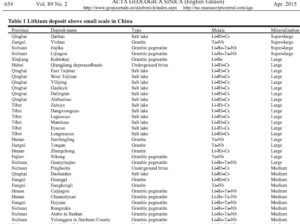

These are the waves rolling in that Tibetans can catch. No need to start from nothing, these are debates happening right now, to plug in to. Critical minerals, including those that come from Tibet, especially lithium and copper, are hot topics, resulting in Western governments rediscovering industrial policy, re-investing in the mines and processors that reduce reliance on China’s reliance on Tibet. It’s a plug & play issue awaiting Tibetan input.

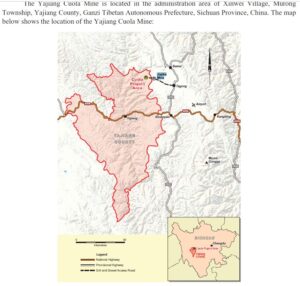

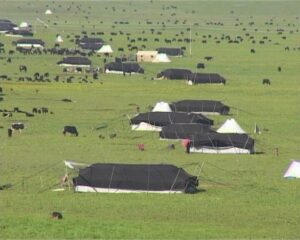

Tibet has been out of sight in recent years, even though there are vivid ethnographies available on the lives of Tibetans only 50 kms from the lithium hills of Nyagchu/ Yajiang.[1] Time for Tibet back on stage.

YOU TOO CAN PERSONALLY CONQUER TIBET

Next off the assembly line is the BYD upmarket U8 SUV, Chinese manufacturers competing directly with Land Rover Defender and Mercedes G-Class for the ultimate in boys’ toys, a heavy beast ostensibly for off-road use, built on a truck chassis, each of the four wheels having its own powerful electric motor. BYD calls it the Yangwang, launching 2023. Instead of a heavy petrol or diesel V8 motor, the U8 requires very heavy batteries if it is to do off-road duty enabling every man who can afford one to personally conquer Tibet, terrain no obstacle. How heavy? Who knows? The lithium batteries alone weigh over 75 kg.

Across Europe and the US there is a bunch of climate activists who call themselves the Tyre Extinguishers who deflate the tyres of urban SUVs, declaring “This is the biggest coordinated global action against high-carbon vehicles in history, with many more to come.” Will they spare China’s battery powered SUV trucks? Probably not.

Tibetans seeking to raise the profile of Tibet in global debate will find plenty who want to listen, from the street avengers of the Tyre Extinguisher brigade to the high level security state insiders of Western governments, who focus on critical minerals and conflict minerals, on how to get their own domestic supply of critical minerals in, and how to keep conflict minerals out.

TIBET’S NEW ALLIES

The world has changed, political nationalism is also now resource nationalism, there is widespread awareness that depending on China for supply of a wide range of metals is foolish, even dangerous. Decoupling and even deglobalisation are under way, and governments of the rich countries are increasingly willing to spend money to support onshore mining and processing of minerals, even if, in typical globalist efficiency models, China is cheaper. Those governments, and their security advisers, need to know that Tibet is a source of both conflict minerals and critical minerals. Documenting Tibet’s position in China’s extractivist regime strengthens the case, in Western countries, for de-risking the supply chain, by reducing dependence on China. That audience is waiting to hear from Tibetans.

There is a new seriousness about forced labour and conflict minerals, new legislation to push the big brands to disclose where their lithium or cobalt comes from, to track rather than conceal the mines and smelters where those metals originate, and to enforce compliance with laws that exclude materials obtained coercively from the supply chain.

This makes for intense scrutiny, from human rights advocates, from security state guardians, from economic nationalists, advocates of revitalised industry policy. That’s a wide range of powerful people, and on the left-right spectrum of rich country politics, both left and right, for differing reasons, want action. They should be told Tibet matters, in all of this intense policy debate.

IS TIBETAN LITHIUM IN TODAY’S LITHIUM BATTERIES?

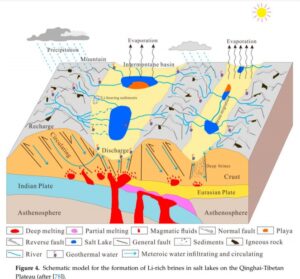

Intense interest, in China and worldwide, on the technologies of lithium battery mass production may also shift lithium extraction sharply towards the currently under-utilised salt lakes of Tibet, rich in lithium, but hard to convert to safe and usable battery material. A tech breakthrough is needed, as Tibetan salt lake lithium bonds chemically with carbon, as lithium carbonate, which is not easily used in battery manufacture. The mega factories prefer lithium hydroxide, which works much better, especially if the batteries are designed to include nickel as well.

This is currently the great limiting factor that restricts extraction of lithium from the salt lakes of Tibet’s Tsaidam Basin, which leads China to instead source much of its lithium from Chile, Argentina, Bolivia (the lithium triangle) and elsewhere. Extracting lithium from high altitude salt lakes in Latin American deserts requires enormous amounts of what deserts most lack: water.

The likely profitability of lithium-ion battery (LIB) manufacture makes for intensive research to improve the tech specifications. We are now in the phase of many players, seeking dominance, who are willing to burn cash to get ahead, including tweaking the tech, to get production costs down, and satisfy the real safety concerns about batteries that overheat and even catch fire, or simply refuse to recharge because of overheating due to impurities.

There is a further reason the tech problems are holding back exploitation of Tibetan brine lithium for now. Again, it’s about the tech bros who want to be able to boast of being early adopters, the fastest guys on the road. Not only do they want speedy acceleration, they demand speedy recharging too. Who wants to wait round while your car is plugged in for the battery to recharge? Not a good look.

Given the size and weight of the battery needed for vroom vroom acceleration, this is a tech problem awaiting solution, despite enormous amounts of money being thrown at it. The marketers see this as essential: with a big enough battery your electric car can travel far, but when it needs to recharge, alpha males need it quick. Wham bam.

EXPLOITING TIBET 2.0

All of this impacts on Tibet. Currently tech problems constrain salt lake extraction, sending the battery companies instead into the mountains, looking and finding rock lithium to be mined. That constraint may lift soon, and the salt lakes again become hot assets. Right now, the boom is in lithium rock mining, concentrated in Kham Kandze Dartsedo, where Chinese mining companies are now making spectacular profits.

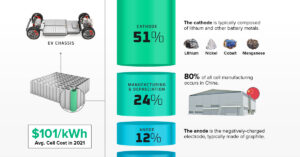

In keeping with the electric car hype, the factories that make the batteries, and the automotive shells that wrap around them, have to be mega factories. In keeping with China’s intense focus on dominating electric vehicle making, those mega factories have to become memes that manifest all the virtues of China’s party-state win-win deal with corporate China.

One of the biggest battery makers, Tianqi Lithium, is locating its latest battery factory in Sichuan Anju, exactly half way between Chengdu and Chongqing, at a time when China is planning to elide these two mega cities into a single megalopolis. The Sichuan basin is a favoured location primarily because endless cheap electricity is available, from the hydro dams on Tibetan rivers. In “normal” summer monsoon seasons the electricity from those many hydro dams is not only plentiful, but largely wasted, as several provincial governments refuse to plug in to the power grids built to transmit electricity, without loss, thousands of kilometres. This colossal wastage is officially known as curtailment or abandonment.

Into the gap energy hungry investors have piled in to the two provinces immediately below the Tibetan Plateau, Sichuan and Yunnan. Quickest were the blockchain “miners” whose heavy use of computing power, running on electric power, was intrinsic to their pitch. Now it is the turn of the battery makers. Does this suggest the making of lovely new green energy is actually energy hungry? Yes.

As the excitement around a tech solution to the climate crisis crescendos, there has also been a slew of studies aiming to quantify the environmental footprint of making and using those batteries right through their full life cycle. As usual, with any simple answer to a complex problem, lithium batteries generate a whole new set of issues.

The Sichuan basin is immediately below Tibet, and Tianqi has turned to rock lithium from Nyagchu Lhagang as a primary source of the raw materials of battery manufacture below. On the Tianqi corporate website, this deposit is pictured, with no mention of Tibet, just “a lithium reserve located in the western region of Asia’s Jiajika mine.” That’s 1200 kms by truck from mine to battery factory, adding to the footprint of “clean” energy. This Rukor blog has reported on Tianqi’s stop/start approach to the Lhagang/Jiajika lithium-laden pegmatite rock deposit back in 2017, and again in 2018. What we failed to notice then was that Tianqi is just one player, with other miners right next door, all vying for access to exploit the veins of a huge lithium deposit, which subsequently turned out to also host rare earths as well.

What we failed to notice was that a notorious sulphuric acid leak that killed fish in nearby rivers, and killed yaks that drank from polluted waters, was right next door. Tibetan land holders defended their lands and protested, only to be ruthlessly repressed, but word got out

“There are pictures of masses of dead fish on the surface of the stream. Some eyewitnesses reported seeing cow and yak carcasses floating downstream, dead from drinking contaminated water. It was the third such incident in the space of seven years in an area which has seen a sharp rise in mining activity, including operations run by BYD, the world’ biggest supplier of lithium-ion batteries for smartphones and electric cars. After the second incident, in 2013, officials closed the mine, but when it reopened in April 2016, the fish started dying again.”

Because local Tibetan communities, shocked at the repeated poisonings, managed to get word out, this sulphuric acid spill was news worldwide, and the Ganzizhou Rongda Lithium mine had to close. To this day any online search for Ganzizhou Rongda [Kandze Prefecture Rongda] takes you to stories of pollution and protest.

A comprehensive analysis that did link Ganzizhou Rongda with the adjacent Jiajika deposit was published in 2016 by Tibet Policy Institute, the think tank of the Dharamsala based Central Tibetan Administration. That analysis, by Tenzin Palden, correctly defined the cause of the fish kill as a sulphuric acid leak. It also identified the river which was damaged as the Lichu, which flows into the Nakchu/Yalong river, the biggest river that merges with Yangtse downstream.

But three years later, very quietly, in June 2019, the mine was back in production, reported only by industry media. This time word did not leak out. The announcement is still on the company’s website, which boasts that at its Nyagchu deposit is “the shallow burial is easy to dig, and the opening cost is low, 且埋藏较浅易于挖掘,开选成本较低.”

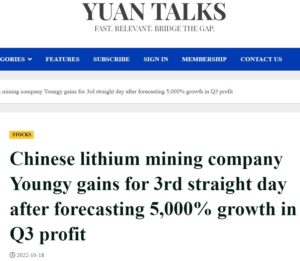

A few months later, in early 2020, the extraction company (having largely dropped the Ganzizhou Rongda bad name) announced, with much propaganda publicity, that output from this lithium mine would be processed 600 kms south, at a new industrial “park” to be built on the banks of the Dadu River, a major tributary of the upper Yangtze, in Kangding [Dartsedo in Tibetan]. The corporate name these days is Youngy, although its corporate website sticks with an earlier incarnation, Luxiang Co. Ltd.

Youngy, which is listed on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange, is these days doing roaring business. For Tibetans focussed on China’s predatory extraction form Tibet, this is the company to watch. You can follow Youngy’s corporate compliance announcements: http://www.cninfo.com.cn/new/snapshot/companyDetailEn?code=002192 or from the corporation’s own website, as usual there is more in Chinese than in English.

Until recently Youngy/Luxiang was primarily in the business of selling street lighting and asphalting to seal urban roads. As the lithium boom beckoned, it pivoted to the much bigger and faster profits to be had from extracting lithium from salt lakes, and from the pegmatite lithium rock deposit at Minyak Lhagang. Now Youngy aims to own and control the lithium production chain, from the Jiajike/Minyak Lhagang mine in Kham Kandze, through to key components of battery production. There is no plan to assemble actual batteries, still less to make cars that wrap around the batteries. That is because Youngy is closely entwined with BYD, currently the dominant lithium car maker in China, outselling Tesla.

Youngy/Luxiang goes back a long way with BYD. Youngy’s boss is Lu Xiangyang, According to Youngy’s website Lu Xiangyang is a co-founder of BYD, back in 1995, together with Wang Chuanfu, today still the boss of BYD. This vertical integration means the lithium rock mined and processed at Jiajika/Minyak Lhagang is destined for use by BYD in its electric cars, SUVs, trucks and buses. Vertical integration means owning/controlling every step from the mine through to the gleaming car rolling off the robotised assembly line, a strategy the reduces Minyak Lhagang to a captive mine contractually bound to just one customer.

PREDATION 101

The rock being mined at Minyak Lhagang [Jiajika in Chinese] is pegmatite, a complex granitic rock that, by its nature, cannot have more than 8% lithium. The Jiajika deposit, though large, averages around two percent lithium, which means a lot of rock has to be not only extracted but also processed onsite, before trucking it 600 kms to the last stage processing at Dartsedo/Kangding.

So sulphuric acid will continue to be used, at the mine site, to create lithium sulphate. Further, the mined rock must first be heated to 1100˚C, then cooled specifically to 65˚ before the acid is applied. That extreme heating, cooling and acid bath all require energy, which comes from the hydro dams China builds on the local rivers as they rush down the steep valleys of the eastern Tibetan Plateau.

Summing up: The impacts on Tibet are multiple: the incursion of a Han workforce constructing and staffing a huge open pit mine with steep walls in an area highly prone to earthquakes, the blasting and removal of millions of tons of granite each year, the hydro dams on Tibetan rivers and the power grids bringing electricity to the mine site so the rock can be heated to melting point, the accelerated cooling to a temperature that won’t evaporate sulphuric acid, the mixing of crushed rock with sulphuric acid to create lithium sulphate. All of these processes happen at the mine site. They have to. No way is crushed rock which is only two per cent lithium going to be trucked 600 kms to Kangding/Dartsedo for processing.

[1] Gillian Tan, In the Circle of White Stones, Moving through Seasons with Nomads of Eastern Tibet, University of Washington Press, 2013

Gillian Tan, Pastures of Change: Contemporary Adaptations and Transformations among Nomadic Pastoralists of Eastern Tibet, Springer, 2019