What to expect in 2023: A series of LITHIUM, LITHIUM, LITHIUM blogs about the short term future of Tibet

Blog 2: WILL CHINA DOMINATE THE FOURTH GLOBAL INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION, POWERED BY TIBETAN RESOURCES?

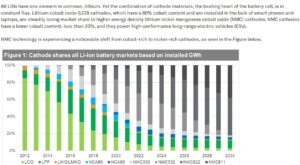

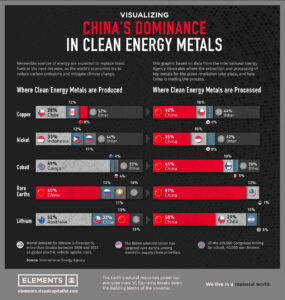

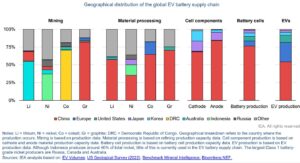

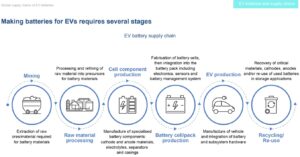

China’s developmentalist party-state is committed to doing whatever it takes to dominate lithium battery production, including state-financed research, subsidies, tax breaks, low interest loans and a global marketing campaign known as Belt and Road. There is a global scientific effort under way to achieve for lithium batteries what has already happened for solar panels, wind turbines and ultra-high voltage electricity transmission, to bring down the costs of production sufficiently for the tech to take off, making extreme profits for whoever can dominate the market. China dominates the production and sales of solar panels, wind turbines and UHV electricity, worldwide, and aims to do the same for lithium batteries.

The impending end of the internal combustion engine is China’s biggest fourth industrial revolution moment. China seeks electric vehicle dominance as the core strategy for overcoming the dominance of Europe, America, Japan and Korea in auto manufacture. The transition away from carbon emitting internal combustion engines, to battery power is China’s big chance to win a race that began a century ago, in which China is a late entrant.

Business schools talk of “first mover advantage”, enabling those who get going first to create lasting dominance -even a monopoly- by being first. This puts later competitors at a disadvantage, trying to catch up. However there is also advantage in being a late entrant, because it enables you to deploy the latest and most efficient production technologies, and you are unburdened by having built and operated expensive legacy plants which are now getting old, and are inefficient compared to the latest advances. China has used its late entrant advantage well, for example in becoming the world’s biggest maker of aluminium, despite having little of the bauxite rock that is the starting point. China’s smelters, many of them in Xinjiang (powered both by coal-fired stations and hydropower) are not only newer and more efficient, but also huge, which means economies of scale. The inexorable logic of globalised competition is expressed in the capitalist adage: get big or get out. The Chinese got big, and working smelters worldwide had to get out, no longer able to compete.

CLEARING OUTER OBSTACLES EXTERNALLY

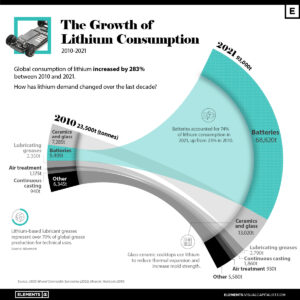

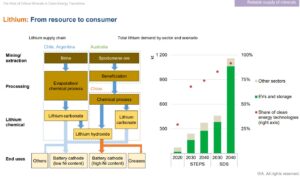

But when it comes to exploiting Tibet to the max, there are obstacles yet to be overcome. The lithium in most of the salt lakes of Tibet is lithium carbonate, increasingly unsuitable for batteries, and needs to be converted to lithium hydroxide, when the battery design includes nickel as well. However this is not readily done, because lithium is resistant to reacting to attempts at chemical transformation. Lithium is not readily bullied or forced to comply with human demands (a bit like the Tibetan people).

This may change, if the current scientific effort succeeds. A Russian team in 2018 reported in depth on the difficulties.[1] The Chileans face the same problem and are working hard to make the lithium carbonate in their dry salt lake beds more usable in batteries.[2]

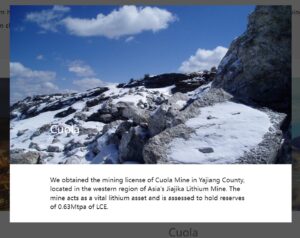

Until a new solution is found, rock lithium is the answer, and China is sourcing it not only from Kandze Lhagang but from West Australia and other global deposits. Actually, the Lhagang deposit is 1200 kms by road from the nearest lithium processing factory in Sichuan Anju, and the deposit owner, Tianqi Lithium, although featuring Lhagang/Jiajika Yajing Cuola on its website landing page, has little intention of intensive exploitation. This is because Tianqi has a much bigger rock lithium project in West Australia. Tianqi fine print says: “we are currently holding Yajing Cuola mine as a reserve lithium asset and we continuously monitor the status of the Yajing Cuola Mine for future development.”[3]

Tianqi says they began developing this deposit in 2012, but ongoing development has been held up by environmental disputes. This Rukor blog reported on the Lhagang deposit back in 2017, when nothing much was happening after a cold winter, and in 2023 still nothing much is happening. Buried in page 48 of a 690 page IPO prospectus, Tianqi warns: “we cannot assure you the development of our Yajing Cuola Mine will resume in the near future.” The initial plan was to extract 600,000 tons of lithium rock a year [Prospectus p 431], an amount big enough to require substantial capital expenditure, yet not big enough to meet today’s soaring demand. Tianqi’s West Australia project is much bigger, three times bigger.

BUY TIBET, SELL TIBET, MINE TIBET?

Can Tibetan be assured Tianqi’s claim to own a chunk of Tibet is just corporate PR? Or is the warning just part of the corporate PR inherent to issuing a prospectus that lists every and all possible risks, thus indemnifying Tianqi against its shareholders? Hard to say. But Tianqi did succeed, with this 690 page prospectus, in raising $1.7 billion from shareholders wanting a slice of the lithium action.

Tianqi is used to making bold initiatives, as a global player, quickly assembling a cartel of lithium producers. That is what matters in today’s neoliberal world. Control, market dominance, making your corporation into a price maker, not a price taker: these are the ways to profit, and achieve China’s national goal of becoming a global power selling its manufactures, made in Chinese factories, worldwide. Corporate financialisaton and national soft power projections are the goals.

In this momentum of rise and rise Tibet plays a part in the narrative crescendo, but it is simplistic to assume the role of Tibet is to supply endless raw materials that feed into China’s supply chains. For decades now China has been able to play a global game, including global sourcing of minerals and other raw inputs, and in an era of cheap fossil fuels was able to build global shipping networks that brought bulk raw commodities across the oceans to China for processing and value adding, capturing onshore the rise in price at every step of the way from ore extraction to finished goods ready for export.

As this era of cheap fuel and little effort to decarbonise is now starting to end, we can look back, at what Tibet meant and means to China, which is a story of more than just exploitation. Tianqi’s splash page boast of its Kandze Lhagang (Yajing Cuola) rock lithium ownership is a clear example. Why the boast, when there is little sign the deposit will be mined any time soon? Is Tianqi saying it has all bases covered, is master of all? If so, is the audience the central leaders in Beijing, the source of concessional finance and political favours that give Tianqi its business success? Not easy questions to answer.

BUILD YOUR DREAMS

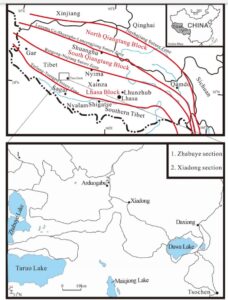

However such questions arise repeatedly. Tianqi has turned to rock lithium because it is so hard to turn the huge accumulation of lithium in the salt lakes of the Amdo Tsaidam Basin into a form suited to mass production of lithium batteries. The same problem applies to other lithium battery makers, such as BYD, a battery maker-cum-car maker that currently outsells Tesla in China, the world’s biggest electric car market. Back in 2008, as the electric car boom was just a glimmer on the horizon, BYD announced it had obtained exclusive rights to a Tibetan lake that had an extraordinarily high concentration of lithium suitable for battery making. Even more remarkably a shrewd counter-cyclical American investor, Warren Buffett, took a sizable stake in BYD, and was filmed, together with Bill Gates, extolling the bright future of Tibet due to BYD’s investment in Zabuye salt lake.

The global investment audience, who couldn’t find Zabuye on a map, but did know who Warren Buffett and Bill Gates are, was impressed.  Under a banner saying “let innovative New Energy technology power the philanthropic light in Tibet and the World”, BYD, Buffett and Gates launched the latest BYD car, with BYD’s exclusive access to the lithium salts of upper Tibet the unique selling proposition.

Under a banner saying “let innovative New Energy technology power the philanthropic light in Tibet and the World”, BYD, Buffett and Gates launched the latest BYD car, with BYD’s exclusive access to the lithium salts of upper Tibet the unique selling proposition.

This wasn’t the first bold move by BYD. It got into the auto manufacturing business as early as 2002, making a clone of the Suzuki Alto: “A large industrial conglomerate wanted to eliminate their ailing car factory, and local politics wanted to keep the factory going and employment secured. Wang [Chuanfu, founder of BYD]could suddenly become a car manufacturer for a minimal price, and he also received a huge piece of land for free, plus some loans at a marginal interest rate. So, in January 2003, he bought Qinchuan Automobile. That industrial conglomerate was China North Industry Corporation, better known by its trading name Norinco. Today Norinco is a huge complex of dozens of companies in the defense, chemical, and mechanical industries, but they have traditionally been arms and ammunition makers.”

Norinco is in the top tier of elite institutions pushing the current strategy of “civil-military fusion.”[4]

Wang Chuanfu has always understood the importance of corporate mythmaking, just like the Silicon Valley start-up entrepreneurs who spin myths of genius. Publicly, BYD was branded as Build Your Dreams; privately Wang said it stands for Bring Your Dollars.[5] Actually, BYD, long before the brand makers got to it, started life as 比亚迪 pronounced bi ya di, chosen by Wang Chuanfu to simply sound nice. A long forgotten start, once the brand developers took over.

Claiming exclusive rights to Ngari Zabuye salt lake was part of this corporate hustle, essential to magnetising capital to burn, in the highly competitive race to market dominance and massive profitability.

Even now, 25 years later, who can say where Zabuye lake is? It is extremely remote, even by Tibetan standards, a basin in the alpine desert of far western Tibet, a vast distance from any lithium market. Like the many self-contained endorheic salt lakes of the Chang Tang empty plain this lake, its surface well over 4000m altitude, is so cold, so high and so lacking in any outlet that it was of no interest to anyone, until expeditionary Chinese geologists tested its slowly desiccating waters and labelled it an especially pure source of lithium. Wang Chuanfu, BYD, Warren Buffett and Bill Gates saw the opportunity to burnish their brand as farsighted entrepreneurs, and a legend was born.

However, very little lithium has actually been extracted from Zabuye, despite investment in walling evaporation ponds to turn brine into salt beds. Since it is at least 1000 kms from Lhasa, on bad roads, with no highway anywhere near, this hardly surprising. But Buffett, “the sage of Omaha”, was praised, as usual, for his foresight, and BYD prospered. Build Your Dreams from Tibet.

THE LATEST TIBETAN HOT LITHIUM SALT LAKE

Enter Zangge. Like BYD in 2008, Zangge is a company in a hurry, determined to crack the lithium boom of 2023, and Mami Tso/Cuo might be the ticket to stardom. Zangge, as its name suggests, is based in Tibet (Zang in Chinese) and specifically in Geermu (Gormo in Tibetan), hence Zang Ge. From its head office in Geermu/Gormo/Golmud Zangge has been busy extracting the salts of the Tsaidam basin salt lakes for many years, for potash fertiliser manufacturing. Since the depleted, over-exploited agricultural soils of China chronically lack potassium, potash fertiliser manufacture is a solid, steady business, even if separating the salts of potassium from the salts of magnesium, lithium and sodium is a dirty business. Farmers don’t mind if the potash is not highly purified.

Then along comes the lithium battery boom, having been forecast for decades as a boom due any moment. Suddenly, Zangge wants to be in the lithium business, and access to a pure lithium lake in the farthest west of the Tibetan Plateau is the way to go.

As in 2008, who could find Mamicuo on a map? No matter. At least it is only 30 kms through the mountains to highway S301, described by https://dangerousroads.org as: “Located in Ngari Prefecture, in the central part of Tibet, in China, the 301 Provincial Road (S301) is a very scenic trip in the middle of nowhere. This asphalted road passes through remote areas, so you need to be prepared. The wind in Tibet is usually quite strong at mountain areas. Even in summer, the temperature might drop from 20°C at daytime to -10°C at night. In July and August, it may rain continually for several days and you even can confront with snowy days. The bigger problem than the condition of the road is extremely low oxygen for engine combustion. It has a well-deserved reputation for being dangerous because of unpredictable snowstorms and blizzards, and driving under these conditions, can be extremely challenging. The road links the cities of Ngari and Nagqu.”

Despite this overstretched logistics chain, Zangge is promising to invest in a substantial extractivist enclave around this salt lake, specifically promising to scale up to extracting 50,000 tons of lithium a year in 2023, and a doubling of that shortly thereafter. Given global demand, these days heavily driven by battery manufacture, this is not a huge amount, but not small either. If we are to believe these figures, this is the start of serious predation of upper Tibet.

But are we to believe? As with Zabuye, appearances are deceptive. It would be risky if advocates for Tibet assumed the removal of Tibet’s mineral endowment is actually happening at Mami Tso.

Zangge and its beneficial owner Xiao Yongming are in a hurry, for a few reasons. Most obviously, lithium is where fast fortunes are now to be made, not so much in the potash fertiliser business. Second, Zangge needs to build its brand, as a coming thing worth many multiples of its actual earnings, while also keeping at bay the investigators of China’s regulators who “On April 24, 2020, the China Securities Regulatory Commission published an article ‘The Securities Regulatory Commission Severely Cracks down on Financial Falsification of Listed Companies’ on its official website, naming the financial falsification of Zangge Holdings, which is characterized by hidden and complicated methods. According to investigations, Zangge Co., Ltd. colluded with hundreds of customers from July 2017 to 2018 and used the peculiarities of bulk commodity trade to commit fraud.” In other words it sought to control potash prices by ruthlessly deploying its market power, and was caught.

Third, for a fast growing company seeking to financialise its operations, owning property is valuable collateral that reassures investors there is a solid business case behind the hype. In a capitalist economy, property is everything, and Mami Tso is indisputably Zangge’s property.

Investors may be inclined to brush aside the case made by the regulators, as share price has risen considerably, and Zangge management keeps share prices high by repurchasing shares from shareholders, something possible only by companies with cash to spare.

On its website, Zangge is gung-ho about Mami Tso. In 2019 Zangge said: “At present, we should seize the great opportunity of western development, take advantage of the rich lithium resources in the west, and accelerate the pace of lithium products deep industry.” By late 2022 Zangge was posting on its website a Q&A: “The company claims that the Ma Min Cuo salt lake 麻米错project will have an annual output of 100,000 tons of lithium carbonate, the first phase of the project can have 50,000 tons, please we ask if the company’s planning scheme is perfect and reliable, from what aspects to ensure the smooth implementation of the project?

“Answer: Dear investor, hello! According to the current development and utilization plan of the Mami Tso salt lake, Mamizou mining industry total planning annual output of 100,000 tons of lithium carbonate, the first phase of the project (2022-2024) to build 50,000 tons of scale, to be invested in the construction of the second phase of the project (expected after 2024) to increase the annual output of 100,000 tons after the conditions are ripe. About the production planning, we have a lot of confidence in the Mami Tso salt lake later production, first of all, for the Mami Tso salt lake technical solutions and salt lake lithium extraction device is in the summary of the Geermu Zangger lithium Industry Co. The leader of the project construction is the salt lake lithium technology and the promoter, has a wealth of large-scale project construction and production experience; all production personnel have participated in the Tibetan mining, already 10,000 tons of lithium carbonate industrial production line construction, operation links, have a wealth of practical experience and excellent professional technology. Thank you!”

How seriously are we to take this prospect? Scraping the salts from a briny lake bed is not at all difficult, but obtaining lithium pure enough to work safely and reliably in lithium batteries is difficult. Lithium carbonate is less suitable for lithium batteries than lithium hydroxide, especially if the batteries also use nickel, which is where the technology is at now. So Zangge’s insistence on its intent to exploit its Gertse county salt lake asset may yet be baseless.

This announcement came at sensitive moment for a company on a fast growth trajectory, which had just suffered a blunt knockback.

Even though Tibetans have not been advocating for Tibet’s lithium patrimony to be classified as both a critical mineral and a contested conflict mineral, the Canadian government has stepped in, reversing a Zangge investment in Canadian lithium. On national security grounds, Zangge was ordered to divest its shareholding. For a company bent on expanding in all directions at once, this was a blow.

Zangge has invoked China’s national pride, and objected strongly to this humiliation: “I believe that with the backing of our strong motherland, we will be able to find effective solutions to ensure the safety of overseas investment.” The next sentence calls on all company staff “ to speed up the investment and construction of the Tibetan Ngari Mamizou Salt Lake, to strive for early construction, early construction and early production, and to make unremitting efforts to ensure national energy security! Thank you!”

There is no Tibetan government empowered to do as Canada has done. Zangge’s ownership of Mami Tso is secure.

What is more likely to spare Tibetan lithium deposits from exploitation is the rough ride of the boom/bust cycle of demand and supply: “Lithium prices crashed between 2018 and 2020 because of oversupply and reduced demand, causing prices to dive from $25,000 per tonne to below $6,000. Lithium prices are currently around $76,000 per tonne of battery-grade lithium carbonate, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. However, Goldman Sachs forecasts a sharp price correction to $11,000 per tonne of lithium carbonate equivalent by 2024, as high lithium prices prompt the development of new sources that will leave the market oversupplied.”

[1] N. M. Nemkov, A. D. Ryabtsev, N. P. Kotsupalo, Preparing High-Purity Lithium Hydroxide Monohydrate by the Electrochemical Conversion of Highly Soluble Lithium Salts, Theoretical Foundations of Chemical Engineering, 2020, Vol. 54, No. 4, pp. 710–718.

[2] Celso Quintero, J. Matthias Dahlkamp, Felipe Fierro, Development of a co-precipitation process for the preparation of magnesium hydroxide containing lithium carbonate from Li-enriched brines, Hydrometallurgy 198 (2020) 105515

[3] Tianqi Lithium Corporation, Application Proof, Hong Kong Stock Exchange, 6

[4] Alex Stone and Peter Wood, CHINA’S MILITARY-CIVIL FUSION STRATEGY: A view from Chinese strategists, China Aerospace Studies Institute, 2021

[5] Leo Breevoort, The Big Read: History of BYD, August 1, 2021, https://carnewschina.com/2021/08/01/the-big-read-history-of-byd/