Anyone for Tibetan matsutake?

Tibet’s famous yartsa gunbu caterpillar fungus are bought and sold dry, with a long shelf life, suitable for distant points of sale; while matsutake are much more perishable, requiring a cold chain from picker to packer to plate. Such is the demand for matsutake, songrong 松茸, that a cold chain has been created, analogous to the global traffic in cut flowers, enabling what is picked today to be on the table of a high end restaurant thousands of kms away, in two days. This is the globalisation of Tibet.

This makes matsutake suitable as a case study of Tibetan entrepreneurialism. What is the role of Tibetans in the global circulation of matsutake? Are Tibetans merely the anonymous, unseen gatherers in the forests, or are they present throughout the commodity chain?

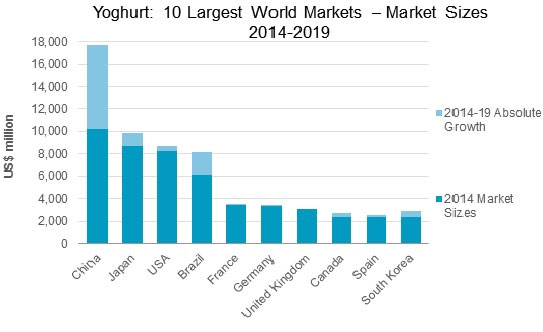

Matsutake make a good story too about the prospects for building cold chains for other Tibetan perishables that are abundantly available, notably milk and the myriad products made from milk. Like the failed Tibetan wool cleaning and value adding industry, dairy has the potential to meet booming demand in China’s cities, yet that potential never attracted Chinese investment. The most obvious path of development for Tibet’s comparative advantages never happened. Sometimes this is attributed to the great expense of establishing a cold chain to keep Tibetan yoghurt, butter, cheese and other dairy products safe in transit over long distances. But if the matsutake business can create an transnational cold chain, why has China failed to do this for dairy? If Inner Mongolia, and imports from overseas now supply most of China’s booming dairy demand, why not Tibet?

FUNGAL FUTURES: WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE MATSUTAKE MUSHROOM BOOM IN KHAM?

A closer look at the matsutake market has six key lessons for the new generation of Tibetan entrepreneurs. Taken together, these six are a SWOT analysis of the opportunities for Tibetan entrepreneurs to move up the value chain.

First, the demand for matsutake is driven by Japanese demand, requiring long haul flights of fresh or frozen matsutake, bypassing lowland China, straight to Japan. This traffic bypasses much of China’s multi-layered commodity distribution system, with its many stages, all out to get a cut of the eventual sale price.

Remote Tibetan schools which learned how to make cheeses from dzo (female yak) milk, found it more rewarding to airfreight mature cheeses to New York, rather than have profits cut to a minimum by selling into China’s urban market, despite the growing Chinese interest in cheese, because so many middlemen intervene. Jigme Gyaltsen, the headmaster of a school in one of China’s remotest prefectures, Guoluo (in Tibetan, Golok) marketed Ragya brand yak cheese in New York, with one kilo selling for what nomads on average earn in two months. The same school has found its profit margin on the New York market, despite higher transport costs, is greater than marketing the cheese to sophisticated Chinese urban consumers, because of the labour-intensivity and multi-layered nature of the Chinese distribution system.[1]

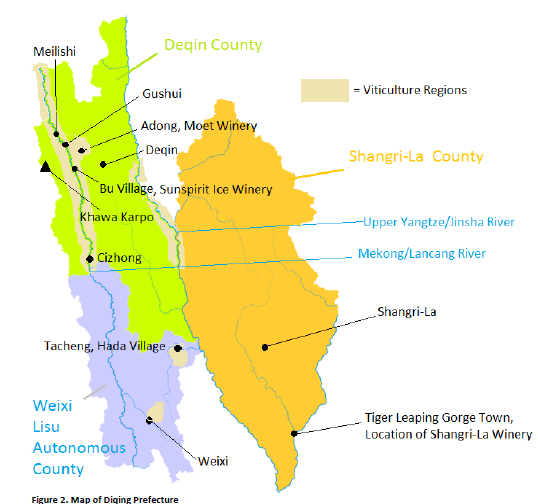

Matsutake, although gathered in the mountains, in dense pine and oak forests, quickly becomes an urban commodity, in Dechen, then Kunming, then Shanghai, en route to Japan. There are already plenty of intermediary steps between Tibetan collectors and Japanese consumers. However, Tibetan entrepreneurs may find online e-commerce channels for directly connecting with and then supplying Japanese matsutake aficionados; simplifying the commodity chain further.

Second, demand has been driven by the distant Japanese market, which remains mysterious and opaque to most Tibetan mushroom gatherers, even though Dechen/Shangri-la is now a major tourist attraction, including large numbers of Japanese tourists. There is opportunity for Tibetan producers to rise in the value chain, add value by adding Tibetan branding and Tibetan authenticity, rather than being price takers caught between Japanese demand and Japanese anxiety over possible pesticide contamination of matsutake from nearby farm cropping practices.

Many players interpose themselves between producer and consumer, including state-sponsored marketing organisations and several NGOs predisposed to assume the level of matsutake harvesting is unsustainable, and that matsutake merits its 1999 inclusion in the UN Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) as endangered.

Because of Japanese fears of pesticide contamination, the perishability of the mushrooms and the assumption that harvesting forest matsutake is unsustainable, the Tibetan collectors are under pressure from several directions, all of which limits the price they get for doing most of the actual labour. A high proportion of the price goes to air freight, cold chain logistics and marketing conglomerates, before the mushrooms land at Japanese airports, where prices again rise steeply.

Since the matsutake boom arrived adventitiously in the mid-1980s, Tibetans have been glad of the extra income, and used their cash earnings to build bigger and sturdier houses from the plentiful timbers of the nearby forests, in customary Kham style. However, the Tibetan producers, never able to combine to take control of supply, have settled for modest incomes, when they could now move to greater control and value adding.

Japanese consumers want not only fresh, palatable and pesticide-free matsutake; they also seek authenticity, sourcing their matsutake consumption from mountain folk they can connect with. Until now this has resulted in several proposals to replicate the farm to fork/paddock to plate traceability of industrially farmed meat, which lends itself to electronic tags and chipping, enabling certifiable origins to be available to end use buyers. There is no way this could be done for each mushroom, picked in the predawn by one of dozens of collectors roaming the slopes with flashlights, pooling their finds in a market town, awaiting the regular arrival of the distributors.

If anything, the demand for purity, freshness and accountability has until now pressured Tibetan gatherers to accept lower prices than matsutake collectors in other pine and oak forests such as Canada and the US. But it is now not hard for seller and buyer to connect directly, to shopify product and sell direct, c2c, collector to consumer. This is the opportunity for Tibetan entrepreneurs.

Third, matsutake is a mature market. This means demand is reliable and there is little likelihood Japan will be able to resume production of its own matsutake on a scale that is anywhere close to meeting demand. There is no way of artificially cultivating matsutake, despite attempts to do so.

The logistic chain is also mature, and is about to shorten and simplify further with the 2020 scheduled opening of an expanded Shangri-la airport, plus the opening of high speed railway and toll road highway in 2020 from Dechen via Lijiang and Dali to Kunming. For perishables that lose value quickly, these new infrastructures shrink the distance between producer and consumer.

In a mature market there are opportunities for consolidation, for dominant players to emerge, who could be Tibetan. A mature market does not always mean a steady price, and matsutake prices fluctuate greatly, usually to the great disadvantage of the Tibetan villagers of the mountain slope forests. Consolidation of a mature market, to oligopolistic control by a few players, is an opportunity to regulate supply, maintain prices and signal quickly to remote gatherers, by mobile phone alerts, when demand plummets or peaks. That way production keeps pace with demand. Price volatility, most recently due to corona virus infection fears, need not be an ongoing defining characteristic of matsutake production.

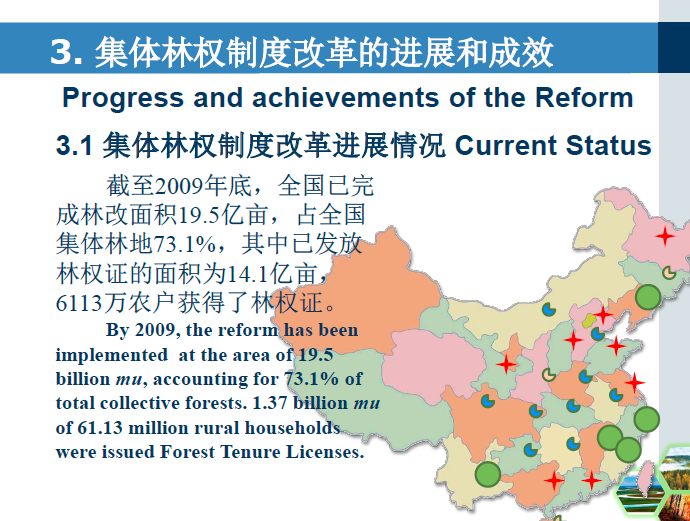

Fourth, official policies, and sudden changes of policy direction, have put a lot of pressure on the Tibetans of Kham Gyalthang, usually in the name of repairing past policy failures. In the official gaze, customary livelihoods including pastoralist grazing and crop farming are now problematic, even environmentally damaging, and require curtailment. Over the past two decades, official programs intended to reforest farmland cleared earlier by official command for local crop self-sufficiency have pressured remote villages to curtail ploughing and cropping, and instead convert fields to tree plantations, with much income loss. Likewise the construction of “ecological civilisation” frequently means herd size limits or loss of land tenure rights altogether, especially in areas designated as exclusively ecological, in which pastoral production is banned.

These pressures, from above, make matsutake all the more important as reliable sources of income, fulfilling locally the modest national goal of moderate prosperity (xiaokang). Matsutake could contribute much more to local prosperity than it has over the 35 years since Japan discovered Tibetan forest mushrooms. Matsutake could do more for poverty alleviation and daily autonomy than it does.

Fifth, prospects for Tibetan matsutake in Japan, and in destinations attracting Japanese tourists, are good. Climate change in Japan raises temperatures in the Iwate prefecture forests where matsutake grows, delaying harvest; and more frequent cyclones also disrupt supply. In Tibet climate change on the midslopes of mountains may mean matsutake will soon flourish at slightly higher altitudes, a slightly higher climb from villages in the valleys. In 2019 prices reached well over $800 per kilo, yet Tibetan producers receive only a tiny fraction. The scope for fair trade rebalancing is great. In Lhasa, matsutake from eastern TAR sell for RMB 250 to 500 per kilo, USD 38 to 77, according to China’s official media. Japanese consume at least 5000 tons a year.

Sixth, wealthy Han Chinese, aware of the cachet matsutake enjoys in Japan, are developing a taste for exotic mushrooms. Urban Chinese demand in Shanghai and Beijing is growing fast, so too is matsutake trafficking with Chinese characteristics. Until now, that has turned Tibetan villagers into competitors, each against all, and undermined mandatory rest days when gathering is banned, in order to give small mushrooms a few days to grow to marketable size.

Initially, when the market was new, local Tibetan cadres instituted rest days as a sensible collective strategy to regulate competitiveness and ensure small matsutake were not picked, and given time to grow. This co-operative strategy was undermined by the aggregators, the first buyers on a circuit going from village to village, who demanded an uninterrupted chain of markets as they made their way up and down endless hillsides on third grade roads. The regulations mandating nonharvest days fell into disuse.

Now Tibetan producers are no longer dependent on the schedules of commercial buyers coming to each village. The era of the drone has arrived, and China’s official media enthuses that it takes only 20 minutes to get matsutake to market, from Tibetan to Han hands, rather than toiling back downhill for hours. The problem is that the drones are mostly in the hands of Han entrepreneurs. This is an opportunity for Tibetans to invest modestly in cheap drones easily capable of transporting the lightweight matsutake down to the demand. Intermediation by drones will require trust between seller and buyer: is this readily achieved?

This is the big question, because it is characteristic of a mature market that supply and demand are largely stable, in balance, enabling investments that are likely to succeed. Risk is low, even if the seasonal harvests in supply districts vary a lot, not only due to climate variations but also corona virus lockdowns, plus, in Tibet, earthquakes and landslides that block highways, especially at the autumnal end of the monsoon season, when the matsutake are gathered.

In a mature market there may be room for new entrants able to find new supplies, or new outlets, such as meeting demand in Chinese cities, or popular Chinese domestic tourism destinations such as Lhasa and Nyingtri. But a mature market makes it hard for new entrants to get into the commodity chain, or set up a new commodity chain, because existing players have both the logistics sewn up, and the networks of distributors, wholesalers and retailers. This means that even if enterprising Tibetans could source more matsutake, Han businesses will still capture most of the value added because they control distribution.

- China’s fungal economy

That is why new technologies, drones and social media, are necessary disruptors of the existing model. There has to be a way to bypass the crony capitalism that concentrates most of the matsutake wealth creation in the hands of Han packagers and distributors. Their near monopoly grew out of state owned enterprises of the Maoist era which had a legal stranglehold on commandeering and selling foods to be sold as exports from China. Those food export corporations earned revenue for Beijing, and their monopoly persisted well into the reform era of the 1980s and into the 1990s. Only gradually were new entrants permitted, and they were characteristically Chinese, in that they blended state and corporate power. “In some cases, the head managers for the Kunming-based private companies were former staff of the foreign trade stations and were able to use their contacts in China and Japan to cultivate relationships for their new company. This was part of a wider phenomenon, in which Chinese companies hired former government employees for their bureaucratic knowledge and social connections.”[2]

That fusion of state and corporate power has always been the primary obstacle for Tibetan entrepreneurs to get beyond the role of raw commodity supplier. China’s state capitalism privileges insiders, redistributes wealth upwards, and reduces those who do most of the actual work of production to incidental roles, as mere gatherers of raw materials.

The disruptive potential of peer to peer direct social media connections between Tibetan villager and Japanese matsutake aficionado, and also drone delivery to new nodes of matsutake aggregation, are promising entry points, bypassing the stranglehold of “the Yunnan Matsutake Association, which comprises the province’s major exporting companies. The provincial government now limits the number of exporting companies, and they in turn have created a matsutake consortium. By 2006, only twenty companies had export licenses, and a number of these companies were led by people with extensive governmental networks, sometimes with a history of working at foreign trade stations in the 1980s.”[3]

Beijing wants national champions that establish Chinese brands in global markets. Yunnan province seeks a Yunnan brand, signifying guarantees of authenticity and freshness, which would only add costly computerised tagging to the labours of the Tibetan forest gatherers. These are all obstacles to Tibetan development, income generation and poverty alleviation through enterprise and initiative.

Instead of documenting certified compliance at every step in a complex commodity chain, new technology simplifies the chain and puts consumer and producer in direct connection, establishing bonds of trust and authenticity. By air from Shangri-la airport in Dechen/Zhongdian to Kunming takes 55 minutes, then on to Shanghai and Japan in hours. No need of freezing, or an elaborate cold chain.

Is this overly ambitious? Is it unrealistic to imagine the Tibetans who produce the matsutake could take control of businesses that export 2000 tons of matsutake from Tibet to Japan annually, for a retail price of at least $2 billion? So little of that retail price –averaged at $100 per kilo- reaches the Tibetans who produce it, and with care wrap the mushrooms in rhododendron leaves for their long transit. Social enterprises serious about empowerment of remote villages have a major opportunity, based on the embedded demand for matsutake in Japan.

A major reason why the matsutake traffic from Tibet to Japan is a mature market is that no-one has ever succeeded in cultivating matsutake. They remain fugitive, ephemeral, arising due to causes and conditions no-one can define or reproduce. This has vexed the Japanese greatly, since the natural occurrence of matsutake dwindled greatly, at just the time many Japanese were for the first time wealthy enough to afford them, and official restrictions on their consumption, hitherto permitted only for the imperial household, had been lifted.

It took decades of scientific puzzlement to figure out why. The main cause of satoyama pine forest decline, and with it, matsutake mushrooms, was acid rain drifting across from China, the air changed by factory pollution, pine trees quite vulnerable, early indicators of the dangers of climate change. Japanese alarm at China’s world factory pollution became a major driver in Japanese development assistance and investment in helping China improve its pollution control.

None of this, however, succeeded in restoring those satoyama pine forests in Japan, still less did restoration efforts bring back the evanescent, elusive matsutake. Those efforts continue, and Japanese researchers are convinced that satoyama forests and their matsutake mushrooms, far from requiring pristine nature, actually require disturbance, even soil degradation, and definitely benefit from having farmland nearby, and farm folk foraging in the forest. “Satoyama are traditional peasant landscapes, combining rice agriculture and water management with woodlands. The woodlands –the heart of the satoyama concept- were once disturbed and this maintained, for firewood and charcoal-making. Restoration requires disturbance –but disturbance to enhance diversity and the healthy functioning of ecosystems.”[4]

If you’ve ever seen the wondrous anime My Neighbour Totoro, you will know what a satoyama landscape is. If Tibetans and Japanese matsutake consumers do eventually generate closer connections, it would be unfortunate if Tibetans took seriously well-meant Japanese suggestions about denuding hillsides, removing soil, grooming and thinning pine forests to yield more matsutake. The Japanese may well be right, that their traditional satoyama forests, where matsutake flourish, are highly disturbed by human intrusions. Ecologists may well be wrong, that restoration of pristine nature should be the goal. But that doesn’t mean recreating satoyama forest in Tibet.

MATSUTAKE, YARTSA GUNBU AND HUMAN RIGHTS

The yartsa bioeconomy of the Tibetan grasslands is certainly the biggest and most spectacular, but far from the only bioeconomy of Tibet. The matsutake economy is measured in the billions of dollars, yartsa gunbu caterpillar fungus in the tens of billions.

Rukor will publish an in-depth analysis of the yartsa bioeconomy. A key question, with both yartsa and matsutake as prime examples: is this development? Are we witnessing the rebirth of Tibetan entrepreneurialism, and a new Tibetan economy, after decades of development failure?

Yartsa and matsutake as new endogenously Tibetan paths to development and prosperity need evaluation, as prospective social enterprises; but also for what they tell us about new era China, which is steadily persuading the world to adopt its redefinition of human rights, as primarily the right to development, only secondarily individual rights such as freedom of speech, freedom from torture and persecution.

China is vigorously pushing, in all United Nations and other international forums, its case that economic development is the only right that matters, all else is secondary. Yet Tibet remains underdeveloped, its traditional comparative advantages never invested in. Tibet remains in disempowered development.[5] China’s failure, over six decades, to integrate Tibet’s strengths in wool and dairy production, into China’s booming demand for them, is a failure to implement the right to development.

As well as the failed bioeconomies of wool and dairy products, which never got linkages beyond traditional markets, there is now the modern matsutake mushroom economy of the oak and pine forests of eastern Tibet, especially in Yunnan and eastern TAR. Like yartsa, this is a fungal economy, based on distant demand by urban consumers with exotic tastes. Like yartsa, matsutake is a big business, with a complex commodity chain and logistics enabling linkages between Tibetans foraging on the forest floor and high end city restaurants not only in China but overseas as well. Both matsutake and yartsa are the leading edges of Tibet’s entry into the global economy.

Yartsa is famous, the matsutake trade less so, in fact many Tibetans have never heard of it. The matsutake mushrooms sprout in a smaller area than the widespread occurrence of yartsa, which sprawls not only across the grasslands of eastern Tibet but in a long altitudinal belt right along the entire Himalayan chain. Matsutake is expensive, a culinary delicacy not only in Japan but also Korea, Thailand and other markets; but yartsa is spectacularly expensive, magnetising resellers in for their margin.

Yartsa is worth a closer look, on Rukor.

And then there’s all those famous wine brands, famous in China and globally, making first rate wines from their Tibetan vineyards, close by the matsutake villages…………………

[11] Tibetan livestock products enjoy bright market prospects, People’s Daily, 19 May 2002, http://english.people.com.cn/200205/19/print20020519_96006.html

http://www.cowsoutside.com/yak_cheese.html

http://www.tew.org/archived/yak.story.html

[2] Michael J. Hathaway, Transnational Matsutake Governance: Endangered Species, Contamination, and the Reemergence of Global Commodity Chains, in Emily Yeh and Chris Coggins eds, Mapping Shangrila, U Washington Press 2014, 159

[3] Hathaway, Transnational Matsutake Governance, 166

[4] Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins, Princeton U Press, 2015, 151-2

[5] Andrew M Fischer, The Disempowered Development of Tibet in China: A Study in the Economics of Marginalization, Lexington Books, 2013