Blog two of three on corona virus in Tibet, China and worldwide

CORONA VIRUS CONTRADICTIONS

The corona virus crisis has revealed that China, at the highest level, is dangerously conflicted by its own contradictions and categories.

On one hand, China wants to be seen as modern, scientific, a leader in rational planning and efficient execution of policy, unhindered by the messy politics of democracy and vested interests lobbying for favoured treatment. China has poured effort into scientific research on almost every topic imaginable and works hard to make much research available in English.

In the field of global health governance, China has been active, promoting itself as an exemplary model of efficient and effective management of health challenges, an inspiration for the developing world.

On the other hand China insists on being unique, exceptional, and not bound to any universals such as human rights. Integral to China’s uniqueness is Traditional Chinese Medicine, a system of treating disease that goes back millennia. TCM has become a core element of Chinese identity and its’ use, in times of crisis, is not the individual choice of an ill person, it is compulsory. Professor Huang Yanzhong, author of Governing Health in Contemporary China commented in early 2020: “throughout modern China, there has always been an interesting marriage between TCM and politics in China. And under Xi’s government, it is now evolving into a symbol of patriotism. You won’t be considered patriotic if you don’t believe in traditional Chinese medicine,” he said.

It has become a matter of national pride that China has a medical system radically different to modern biomedicine, with not only different ingredients but a different imaginary of what it is to be human, what dis-ease is, and modes of treatment. Yet an enormous effort goes into laboratory work to validate TCM scientifically. For example, the officially recommended use of bile forcibly extracted from living bears in cages, as an effective treatment for corona virus infection, has dozens of scientific reports on its use in many other diseases.

This unresolvable tension between TCM and biomedicine, now results in tragic absurdities, in this time of pandemic. Almost certainly this corona virus, utterly new to human lungs, has existed for a very long time in bats, and was transmitted to humans via some intermediary species, no-one is yet sure who. What is clear is that the Wuhan wet market, a jumble of wild caught animals piled on top of each other in cages, awaiting slaughter, was the ideal setting for a virus to jump, from bats to some other species and then to humans. The logic behind making a health soup from bats, and consuming wildlife in feasts of conspicuous consumption, is that they are all TCM ingredients, known for bestowing health.

Thus promoting TCM means promoting the consumption of the same species that caused the corona virus contagion. This is the central contradiction.

This contradiction has not been resolved by China recently enacting further legislation forbidding the eating of wild animals; as the law does not prohibit their use, dried, in TCM and even permits animals seized in official raids to then be quietly sold to TCM compounders. The contradiction is now acute, exacerbated by official decrees listing specific traditional treatments whose approval has been validated, in the middle of a pandemic. National Geographic says: “This recommendation highlights what wildlife advocates say is a contradictory approach to wildlife: shutting down the live trade in animals for food on the one hand and promoting the trade in animal parts on the other.”

This contradiction has arisen before, as several contagions have arisen in China, and several attempts at legislating to stop global trafficking of wildlife to China have failed. The politicisation of TCM as patriotic, used by decree on as many as 90 per cent of corona virus patients in China, only makes the contradiction ever more acute.

Further, this is no longer China’s problem alone. China, promoting TCM as a global export market, has made the status of TCM a regular priority of its soft power projection diplomacy, especially within the UN World Health Organisation.

For 12 years, WHO’s director-general was Dr Margaret Chan, from 2006 to 2017, when Ethiopian doctor Tedros Ghebreyesus took over. China was understandably proud it had a Chinese citizen heading a UN agency. China saw international recognition of TCM as not only an export market opportunity but as soft power projection, an example of why China is to be accepted on Chinese terms, as unique.[1]

WHO bowed to China’s political pressure to exclude Taiwan, a costly exclusion in this time of pandemic, as Taiwan managed a serious corona virus contagion effectively and very differently to China.

Professor John Fitzgerald, who for years headed the Ford Foundation in China, reminds us: “TCM is not quite the grass-roots cultural practice that it might appear to outsiders. It is deeply embedded in the party’s management of daily physical health in China, where it is allocated a respected place alongside evidence-based medical practice, or “Western medicine” as it’s known in China. “Chinese medicine treats the basics; Western medicine treats symptoms” goes the saying. What’s more, TCM has the backing of Xi. A thriving and growing international consumer market for pangolin meat and scales, rhinoceros horns, leopard bones, tiger plasters, black bear bile, donkey hide, and kangaroo penises is a predictable outcome of the grandiose repackaging and political marketing of TCM as a global equivalent to evidence-based medicine in Xi New Era of global leadership.

“TCM is also a potent weapon in the party’s ongoing struggle with universal values and human rights. Beijing tends to view and portray human rights and values as a nasty concoction of false hopes and evil intentions brewed up by US institutions and liberal media to promote the global hegemony of the West. In place of universal values, Xi champions his own brew of national values blended with national folk science and culture. He is also building the propaganda platforms and communications infrastructure needed to deliver his concoction to homes throughout the world.

“At the moment the corona virus was leaping from animal to human hosts under the Huanan market scenario, Xi attended a meeting to endorse TCM. On October 25, 2019 he told a national TCM conference in Beijing that traditional medicine “is a treasure of Chinese civilisation embodying the wisdom of the nation and its people”. In May 2019 the organisation’s governing body, the World Health Assembly, duly agreed to include a chapter on traditional medicines in its guide to acceptable global health practice, the International Classification of Diseases — an authoritative document that assists doctors around the world in diagnosing medical conditions.

” The world scientific community was appalled. The editors of Scientific American branded the decision “an egregious lapse” in evidence-based scientific practice. Nature warned in an editorial that the decision could backfire on WHO in years to come. The organisation’s endorsement of practices that were untested and potentially harmful was “unacceptable for the body that has the greatest responsibility and power to protect human health”.

When it came to endangered wildlife, such as panthers and pangolins, it did not take long to backfire. Wildlife conservationists feared the worst following WHO’s decision. TCM could turn out to be the major political and cultural vector for this devastating global pandemic. If wild game is involved, then TCM has a lot to answer for.”

[1] Huang Yanzhong, Pursuing Health as Foreign Policy, Indiana Journal of Global legal Studies, 2010, 17 #1, 110-

Huang Yanzhong, Engagement in Global Health Governance Regimes, chapter in The Sage Handbook of Contemporary China, Sage, 2018

A NOVELIST IN THE EPICENTRE

We can now turn to other Wuhan voices, from within the epicentre, notably the Wuhan novelist Fang Fang, who used to work unloading ships sailing inland up the Yangtze to Wuhan, a worker not in a hospital but on the wharves. Fang Fang turns to the baogao wenxue 报告文学 reportage literature genre to capture the mood of her city in lockdown. Fang Fang embraces baogao wenxue, literary investigative reporting, despite being herself isolated, yet able to read the emotions of her fellow Wuhaners.

Fang Fang delivers a low key letter from the future, our near future as we start getting used to isolation. For her, the leap day last day of February was already day 38 of lockdown:

People are a bit depressed, in Wuhan, that’s what I feel strongly. Even my cheerful colleagues so far don’t want to talk. At home, almost no one opens their mouths. Is it because everyone is only thinking about the new episode of the television series? I wish it were so. Being locked up at home for a long time with a ban on going out, you need a strong will to support it. In Wuhan, everyone feels a kind of indefinable pressure, which you can hardly understand, I’m afraid, when you are outside. We can never have enough fine words to praise the sacrifices made by the people of Wuhan during this epidemic. We persevere in our support for all official directives, we continue to follow and comply with them. We’re already at 38th day of quarantine.

Fang Fang’s translator (into French), Brigitte Duzan, reminds us how the whole of China turned to her, for a dose of reality, unfiltered by the imposition of censorship and propaganda, until it was.

During the entire month of February, and again in March, the first thing people did when they woke up in the morning, in Wuhan but also in whole China, was to rush to read Fang Fang’s “Diary”. No one wanted to watch CCTV reports or read articles from the People’s Daily. She began it the day after the imposition of the quarantine, to report the feelings of the inhabitants, but also to record the most trivial events of everyday life in order to give a true picture of life in the city.

Fang Fang’s diary will have been a ray of light for everyone in this dark period. It brings out all the fragility of life, despair, helplessness, daily struggles and the worst suffering.

It has often been deleted, but we continue to read it. It is also a window open on the city for the outside world, to try to understand the life of the city from the outside.

Despite the inevitable censorship by the jealous gods of the party-state, Fang Fang’s daily posts are still available, in the original Chinese: http://fangfang.blog.caixin.com/

All wet market pix in this blog sourced from

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzU4MTY2ODQ3Mg==&mid=2247518492&idx=3&sn=2b0d64a17fc7a78efa7751eea3f5f602&chksm=fd46d20bca315b1dcd0821440592f30e5403f608f86dd91ddf1bf23425c2f788d8c77b5e474a&scene=27#wechat_redirect

SONGS OF TRIUMPH AMID SONGS OF MOURNING

Wearied by the lockdown dragging on, still determined to capture the people’s emotions she gathered daily by phone, by social media, nothing wearied Fang Fang as much as the capture of Wuhan by the propaganda apparat, out to proclaim itself as the source of all that is good, successful, competent, capable, exemplary and suitable for export worldwide. Before the dead were cold the party-state supervened.

In a brief message entitled The turning point is not yet here, who is already singing a song of triumph?《拐点 尚未 到 , 谁 已 在 高歌?》She writes: The pain of Wuhan people cannot be relieved by shouting slogans.

Fang Fang is in shock at this brazen appropriation, and insistence on gratitude to the omniscient party-state and its core leader. After the acute cabin fever of lockdown, it is enough to wonder about the daring thought of going out, into the Wuhan urban world again:

As the time spent locked up at home lengthens, I wonder if, when I go out, I will get used to it. And especially if I’m going to want to go out. Today, my neighbor Tang Xiaohe sent me photos of the East Lake, as if taken by a drone, telling me that they are recent. The lake is deserted and peaceful; the plums are in bloom, alternating white and red, it is incredibly beautiful. I forwarded these photos to a colleague, and she told me that when she saw them, she wanted to cry. Ah … a spring in vain. Red apricot blossoms, red Japanese apple trees. Look at the tips of their branches, they blame the sky in silence.

In the face of official capture, censorship and compulsory forgetting, Chinese writers deploy all their skills to urge everyone to remember. Novelist Yan Lianke, in an online lecture to his Hong Kong students, says:

The ability to remember is the soil in which memories grow, and memories are the fruit of this soil. Possessing memories and the ability to remember are the fundamental differences between humans, and animals or plants. It is the first requirement for our growth and maturity. Yet, songs of victory are already echoing all around. All because statistics are looking up.

Bodies have not turned cold and people are still mourning. Yet, triumphal songs are ready to be sung and the people are ready to proclaim, “Oh, how wise and great!”

We must not be like Ah Q (阿Q, a fictional character in Lu Xun’s novel, characterized for deceiving himself into believing he’s successful or more superior than others), time and again insisting that we are victors even after being hit, insulted, and being on the brink of death.

Our memories have been regulated, replaced, and erased. We remember what others tell us to remember and forget what we’re told to forget. We stay silent when we’re asked to and sing on command. Memories have become a tool of the era, used to forge collective and national memories, made up of what we’re either told to forget or asked to remember.

Especially since the SARS epidemic from 17 years ago, and the escalation of the current Covid-19 epidemic seem as if they are works by the same theatre director. The same tragedy is re-enacted before our eyes. As humans who are but dust, we are incapable of finding out who this director is, nor do we possess the expertise to recover and put together the scriptwriter’s thoughts, ideas, and creations.

Novelist Yan Lianke’s cry for memories to persist is part of a huge effort to preserve writings censored by official diktat, even to translate many into English. Fang Fang’s Wuhan Diary, a full English translation, arrives in August.

Yan Lianke asks the key question: “Who erased our memories and wiped them clean?!

Forgetful people are, in essence, dirt in the fields and on the roads. Grooves on the sole of a shoe can step on them in whichever way they please.

Forgetful people are, in essence, woodblocks and planks that have cut ties with the tree that gave them life. Saws and axes are in full control of what they become in the future.

If reporters do not report what they witness, and authors do not write about their memories and feelings; if the people in society who can talk and know how to talk are always recounting, reading, and proclaiming in pure lyrical political correctness, who can tell us what it means to live on this earth as flesh and blood?

History becomes a collection of legends, of lost and imagined stories, that are baseless and unfounded. From this perspective then, how important it is that we can remember, and possess our own memories that are neither revised nor erased.

Something is amiss when we face centralized and regulated “truths.” The little voice in us will say: “That’s not true!” While memories may not give us the power to change reality, it can at least raise a question in our hearts when a lie comes our way. We can already hear victory songs and loud triumphant cries from all around us. If we can’t loudly question the source and spread of Covid-19, then may we softly mutter and hum, for that is also a display of our conscience and courage.

If we can’t speak out loudly, then let us be whisperers. If we can’t be whisperers, then let us be silent people who have memories.”

Why is the party-state so insistent that it alone authored the fight against the corona virus, and it alone succeeded? Perhaps to cover up its guilt at denying any problems existed, in the first weeks of the virus spread, when decisive action could have greatly limited its global leap.

TIBET: A LABORATORY ON THE FRONT LINE

For Tibetans the post corona world won’t be the same, in several ways. The corona crisis was an opportunity for the security state to tighten its grip. The story of the corona outbreak in Kham Kandze Tawu is of intensive immobilisation of an entire county, while surveillance officials combed their contact tracing apps to track who had been where and when, until they nailed “patient zero” and everyone who had been in contact with him.

This normalises mass surveillance, grid management and other tools of repression. Repressing viral transmission has been the ideal vector for transmitting extreme control as the new normal. The upside, once corona lockdowns ease, is that if you did stay in place, did obey orders, did self-quarantine, you may now move around, displaying at the checkpoints the green QR code on your phone app certifying you are now permitted to move. That is how social credit works: if you are compliant, the state benevolently restores your rights; if you are noncompliant you are punished. At any moment, your rights can be revoked.

China now proclaims it is exemplary, a model for the world. China has issued an official timeline of its corona virus response, airbrushing out its many weeks of suppressing the viral truth. Fortunately, a small army of Chinese techies is working hard to preserve what is officially being erased, and much of this is becoming available in English.

This virus did not originate in Tibet, but in Tibet China trialled many of the techniques of control, denial, silencing, surveilling, editing and rewriting the facts, that have now spread across China. Tibet has long been China’s laboratory, testing grid management lockdown, silencing dissent, criminalising protest. Tibetans, especially in central Tibet (Tibet Autonomous Region) have lived through such curtailments of basic human rights for decades.

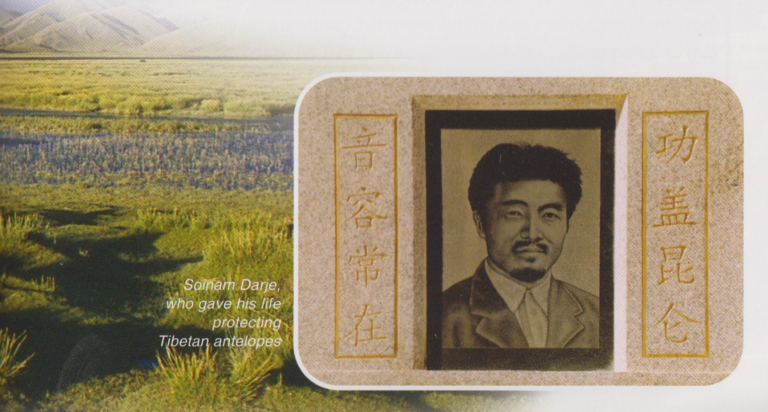

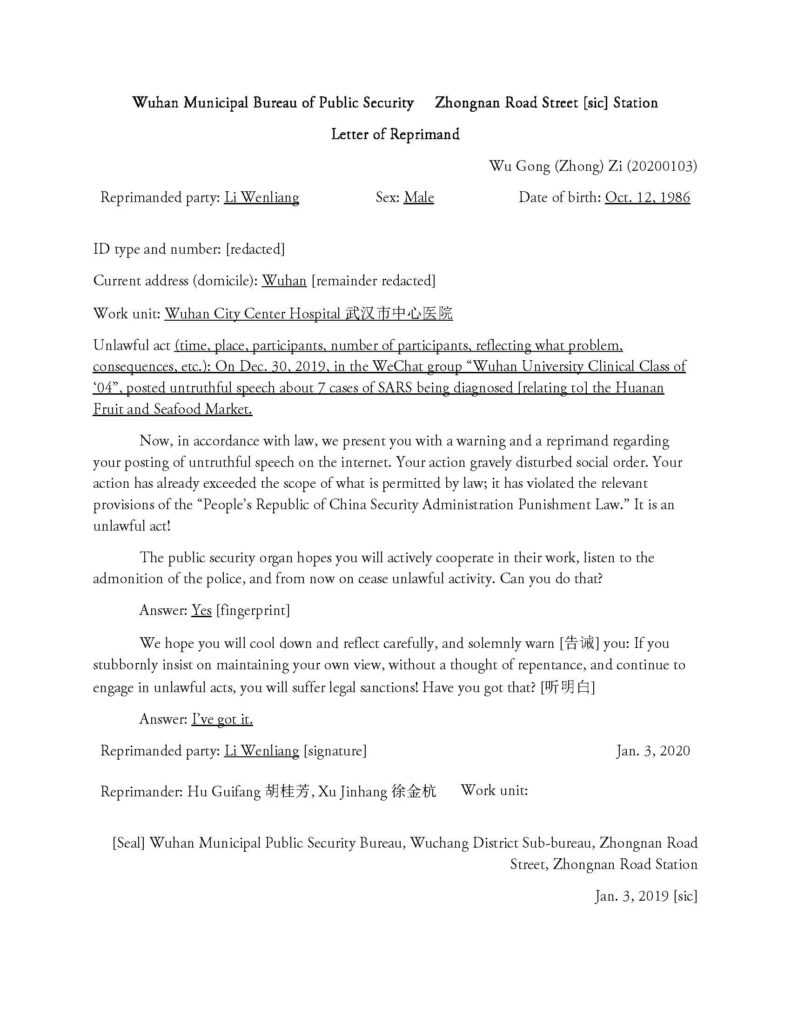

Also not new to Tibetans is the extraction of just one man from his community, to be enshrined as a martyr, who died for the greater glory of the party-state. In the corona crisis the courageous doctor Li Wenliang was the first to alert Wuhan to the unseen danger spreading everywhere. Dr Li was then hauled in by the security state. Not only was he officially reprimanded for spreading “rumours” that were true, he was made to sign a humiliating, enforceable confession and promise to toe the official line.

That is how the party-state, at local level, routinely suppresses anything that might ruffle “stability.” Zhao Shilin, a courageous former professor of religion and philosophy at Minority Nationalities University, Minzu daxue, explains: “For a long time, the ingrained notion of “stability overrides all” has twisted how we treat so many societal problems. Upon careful examination of this “extreme stability” principle, all negative events, including both natural and made-made disasters, are seen as threats to stability. Both undermine the system’s image as being stable. As a result, a kind of rule has formed which holds that if any negative event can be handled in a low-profile fashion, then it should be. And so, the focus of this so-called stability is on the safety of the political regime, rather than the wellbeing of the people.

“To date, authoritative Chinese and foreign sources of information are all constantly confirming the following: Policy makers knew about the present outbreak from the very beginning, ordinary people were the only ones who didn’t know, and yet ordinary people are the only ones who suffer the consequences. I regret to say, since the beginning of the epidemic, the underlying psychology of policy makers deliberately concealing the epidemic is this: Put the safety of the regime before the safety of the people; put the stability of the regime before the stability of society; put the esteem of the regime before the rights and interests of the people. Because of this, officials on all levels work together to deliberately conceal the outbreak—at the expense of people’s lives, with no regard for the fact that concealing the truth would lead to further spread of the outbreak and provoke societal unrest. This is precisely what is meant by “putting political security first.”

“Policy makers hoped in their hearts that they could make it through this outbreak on blind luck. They were unable to quickly mobilize society to implement effective prevention and control measures as early as possible, missing the golden window again and again, and thereby resulting in the fierce spread of the outbreak. This has a direct connection to this extreme, twisted, regime-based, “putting the political regime first” social stability way of thinking.”

In Tibet, stability is always the framing device for responding to any Tibetan protests; immediately making any call, even for China to obey its own laws, illegal, to be repressed as forcefully as deemed necessary.

The harsh language of infection control is familiar language to Tibetans: “The Tibet Daily reported March 12 that “the security bureau office in Lhasa is striking back against those social elements who go against the measures of containing and controlling the spread of COVID-19.” “Keeping the safety and welfare of the people is the paramount duty of the security forces, so it is only natural that in instances where people illegally breach government measures, they are met with harsh punishment,” the Daily continued. “Those guilty people were given a trial and sentenced in accordance with the law,” the report said, adding, “The police were in the forefront of maintaining law and order during this crucial point in time.” Lhasa police officially registered seven instances of people violating coronavirus prevention and control measures laid out by the government, with 10 people arrested, the report said.”

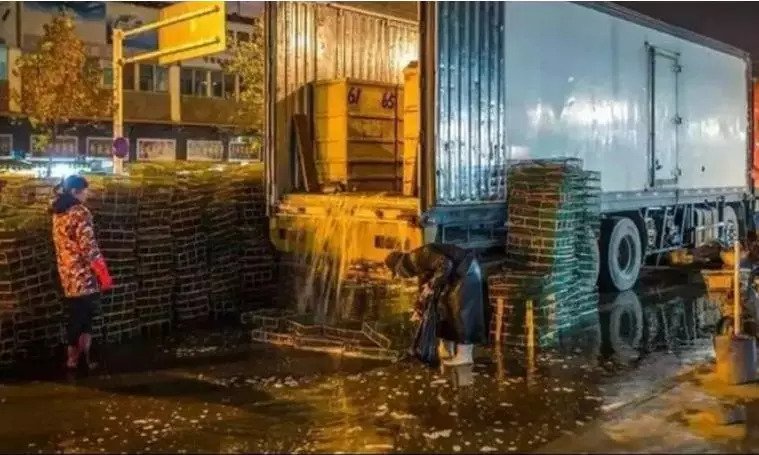

ENTERING THE WUHAN WET MARKET

That brings us back to the Wuhan wet market, where it all started. Those who suppose China is a fully centralised command and control authoritarian dictatorship should be amazed the Wuhan wet market existed, kept expanding, kept supplying delectable wild animals, live, for the boastful consumption by rich tuhao, mostly men. When the inevitable happened, and a virus of bats jumped species and ended up in human lungs, no-one should have been surprised. The Wuhan wet market was chaotic, unregulated, a haven of corrupt officials turning a blind eye to the highly profitable trafficking of wild animals, kept alive in cages until the moment of consumer purchase and slaughter. In those piled cages, animals had no choice but to piss, shit and bleed on each other, ideal circumstances for viruses to discover new hosts, new species to infect.

Not only was there nothing unusual about the Wuhan wet market, the suppression of inconvenient truths was also nothing unusual. The primary responsibility of local officials is to prevent anything that might disrupt order and stability from becoming widely known, triggering alarm. Suppression of information, at the most local level, is the norm, for fear of angering those higher in the hierarchy. Promotion depends on maintaining order above all else. The cadre who fails to keep dissonant facts secret is classified as a failure, to be denied promotion.

The party-state cadres of Wuhan did what was expected of them. Only when Covid-19 cases spiralled so fast did it become apparent the truth had been suppressed for at least three crucial weeks, probably longer, squandering the only window for suppression, not of truth but of virus. Once it was all out of hand, Wuhan cadres got the blame, and some were sacked.

This is why Yan Lianke urges fellow Chinese to remember what can no longer be publicly said. This is why the propaganda machine is in overdrive, declaring itself the protector of the people, from start to finish.

Part of this official response is to legislate to forbid the consumption of wild animals, if sold for eating by pampered individuals. This legislation forms part the official boast that China is uniquely capable, decisive, interventionist and swift in rectifying wrongs. Reports sound as if the full force of authoritarian governance now forbids wildlife capture, sale and slaughter, as if China at last is taking seriously the global plea to end the trafficking in rhino horn and elephant tusks, in tiger bones and pangolin scales and shark fins and much more.

However, as was the case with past bans, the new law persists in permitting the slaughter of animals for use in traditional medicine, and the huge industry of raising innumerable species in cages for slaughter, for manufacture of medicines with Chinese characteristics.

Peter Li, Professor of East Asian Politics at the University of Houston-Downtown reminds us: “Wuhan’s Huanan Seafood Market, where COVID-19 originated, had a section for selling wild animals. This part of the market was filthy, smelly and chaotic. Cages of animals which had either been caught in the wild or bred in captivity – many of them lethargic, sick, and dying with open wounds caused during their capture and transport – were stacked one on top of another. The animals inside the lower cages were soaked in the blood, excrement and urine of the animals incarcerated above. Carcasses of slaughtered animals were strewn on the ground, allowing blood to flow indiscriminately. Suffering was everywhere. Traders were left to their own devices and could not care less about the animals. The market was like an ‘independent kingdom’ beyond the reach of the laws of the People’s Republic of China.

“Wuhan’s wildlife wet market is not atypical. In China, the wildlife business sector enjoys many privileges and disproportionate influence. The Chinese authorities enacted a special national law in 1989, the Wildlife Protection Law (WPL), which was for the protection of this business interest rather than wildlife. To the consternation of critics, the WPL that was revised in 2016 remains a law which defends the wildlife business interest.

“Wildlife is still designated as a ‘resource’ to allow for its uninterrupted use for human benefit. In effect, the revised law has actually rolled back the limited gains made by the country’s conservation efforts. By including a so-called ‘captive-bred offspring’ concept (Article 25), the revised WPL has prepared the ground for re-opening the tiger and rhino trade.”

Despite the impressively authoritative language of the latest law, and accompanying propaganda, a loophole continues to allow the use of dried animal parts in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), and allows the industry farming many species for medical ingredients to persist.

Despite widespread horror, within and beyond China, at the cruelty of the Wuhan wet market and its pampered wildlife consuming customers, wildlife farming is still allowed, and wildlife caught in the wild for consumption, then apprehended by police, may still be lawfully returned to the TCM market, to be used in TCM manufacture. Horror at hunting, caging and consuming wildlife is a common reaction within China, more so now than ever. The horror pictures of the Wuhan wet market were posted by local photographers in Wuhan, to face everyone up to the cruelty of treating wild animals as delicacies to bribe your boss with. The captions explain that “at first there were only more than 400 stalls. Later expanded several times. Now the area reaches 50,000 square meters, equivalent to 7 football fields. The number of shops has also increased to more than 1,000, making it the largest aquatic wholesale market in Central China.”

This ongoing power of wildlife trafficking as an industry says a lot about China’s insistence, as a matter of national pride, that everything must have Chinese characteristics, including corona virus treatment. Official propaganda emphasises that 90 per cent of Chinese treated for corona virus infection were treated with TCM, and the fact that most recovered demonstrates the effectiveness of TCM, not as a cure but as effective symptomatic relief.

The use of TCM to treat a disease caused by the TCN demand for animal parts is not just an embedded cultural preference; it’s a command, from the highest level. CCP Politburo member Sun Chunlan 孙春兰, who has been charged with a leading role in handling the coronavirus epidemic, writes in the party’s top ideology journal Qiushi or Seeking Truth that TCM must be administered to all corona virus patients. This, she says, is one of the “five optimisations” of the official corona virus strategy, thus demonstrating to the world China’s responses to the epidemic had “fully demonstrated China’s power,” “the political advantages of the CCP and the institutional advantages of socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

TOO BIG TO FAIL: CHINA’S ANIMAL FARMING

The legislative exemptions for the wildlife farming industry are a reminder of how big and politically powerful it is. This is seldom mentioned, not even by those who blame China for corona virus and much more. China’s wildlife farming industry includes 6.3 million direct practitioners and a total output value of $18 billion in 2016 and has only grown since.[1]

We now have detailed information about this influential, ongoing industry and its own Chinese characteristics, from fieldwork interviews with Chinese wildlife traffickers and their official enablers, thanks to Utrecht University criminologist Daan van Uhm:.

“Gift giving is a common cultural practice in China in all areas of life, both in informal relations and in dealing with official institutions. Reciprocity is a foundation in the Chinese social intercourse as accepting a gift without reciprocity is perceived as morally wrong. The Chinese practice of guānxì (關係) is the basic dynamic in Chinese personalized networks of influence and refers to favours gained from social connections. The Chinese largely rely on this form of personal informal network for many aspects of their life and reciprocal benefits are necessary to maintaining one’s guanxi. This provides a familiar framework for illegal wildlife businesses with low penetrability as it creates an effective insider-outsider system; enforcement agents are regularly outside the guanxi trading relationship. Family, cultural and ethnic ties play an important role in different stages in the wildlife trade in China. Business partners would preferably belong to the same ethnic Chinese group from the same region and social ties with family and friends would guarantee the secure network.

“Our findings suggest that social ties with officials occur frequently in the illegal wildlife trade. For example, border officials take advantage of their privileged access to confiscated wildlife contraband to obtain goods that they can sell to contacts involved in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). For such informal reciprocal agreements, guanxi was acknowledged as a vital determinant as to whether individuals would collaborate with one another. As one respondent explained: ‘Middlemen do have such relations with border officials […] If you have money and guanxi, you can pay the border control’. This informant underlined that the favours gained from social ties is fundamental in this reciprocal relationship to benefit from these special services.

“In another example of how a symbiotic relationship can occur within the illegal TCM trade occurs when goods are seized from airline flights. For instance, one representative of a well-known TCM trading company outlined: ‘If smugglers from Myanmar and Laos are caught and the Chinese police seize a rhino horn, they resell it to us illegally. If the stuff (rhino horn) is confiscated by an international airline, they (government officials) burn it’ (Lihua).

“Army personnel would utilize their position to allow traffickers to cross borders unimpeded. As one middleman in Anguo admitted: ‘My friend works as a soldier at the Guangxi border. Through this connection I can pass the orders across the border’ (Zhen). Several TCM doctors interviewed also highlighted how TCM clinics would develop a reciprocal relationship with government officials. Specifically, TCM clinics would pay government officials with gifts or money to sell certain products, such as pangolin scales or saiga horn.

“One TCM doctor in Chengdu described how government officials did not formally protect TCM traders, but did make arrangements so that other officials do not disturb or stop them. For example, it was suggested that such officials would utilize their own connections and networks to ensure that specific TCM clinics would not be inspected. Another TCM doctor explained that ‘if you can pay enough [gifts or other services] you can sell the products’ (Hua). Some study participants surmised that the diplomatic immunity afforded to such officials was one of the main reasons as to why they helped TCM traders, while others believed that the existence of an informal TCM market alongside the official provides opportunities for bribes. On the other hand, antithetical relations exist between legally registered TCM companies and illegal TCM traders in the context of competition; the same species were illegally offered on the black market. For example, both saiga horns and pangolin scales are sold by legitimate companies, but generally are illegal and hidden under the counter in plastic bags or pangolins are mainly kept in glass jars. Finally, study participants explained that the existence of tiger farms and corrupt activity resulted in the continued use of tiger parts for TCM.

“In the 1980s two tiger farms were developed by the Chinese government to breed tigers for the commercial supply of bones for TCM. While the government banned the use of tiger products in TCM in 1993, respondents stated how government officials still provide legal documents to tiger farms to produce and sell banned tiger bone wines.

“We refer to this type of activity as ‘legal exploitation’. We can speak of legal exploitation when legal actors issue authorisations for transactions that are used for illegal activities by illegal actors. In this case, it is not necessarily that legal and illegal actors benefit each other (‘systemic synergy’) or that consciously mutual benefits between the legal and illegal actors exist (‘reciprocity’ or ‘even exchanges’). Several TCM traders confirmed that they buy their tiger products from tiger farms in China. As offered by one employee of a tiger farm: Government officials allow us to sell the wine. They gave us a certificate to sell the tiger bone wine, because we have many tigers. Around 100 tigers are born, and a lot of our tigers die every year. Yes, all tigers that have died here are kept in ice.”[2]

The trafficking of wild animals into China and across China, alive and dead, for pampered consumption as a bribe received, or for use in TCM, is a deeply entrenched industry that has managed to evade effective regulation many times in recent years. It is an industry steeped in patriotism, in Chinese characteristics. It is the vector of transmission of corona viruses past and again in 2020. It is unstoppable, even by a highly centralised authoritarian regime.

Hence the horrors of the Wuhan wet market, now being bulldozed. It and similar markets in cities across China will not die, because they are essential to the giving of gifts and staging of banquets to bribe those above you, who hold power to permit or deny your business, or loan the capital your business needs in a system where bank loans go overwhelmingly to state owned enterprises. The same applies to the trade in Tibetan yartsa gumbu caterpillar fungus, a key commodity in the business of bribing pampered cadres.

Sonia Shah, the author of PANDEMIC: Tracking Contagion from Cholera to Ebola and Beyond (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2016) reminds us that in the wet markets “wild species that would rarely if ever encounter each other in nature are caged next to one another, allowing microbes to jump from one species to the next, a process that begot the coronavirus that caused the 2002–03 SARS epidemic and possibly the novel coronavirus stalking us today. But many more are reared in factory farms, where hundreds of thousands of individuals await slaughter, packed closely together, providing microbes lush opportunities to turn into deadly pathogens. Avian influenza viruses, for example, which originate in the bodies of wild waterfowl, rampage in factory farms packed with captive chickens, mutating and becoming more virulent, a process so reliable it can be replicated in the laboratory. One strain called H5N1, which can infect humans, kills more than half of those infected. Containing another strain, which reached North America in 2014, required the slaughter of tens of millions of poultry. The epidemiologist Larry Brilliant once said, “Outbreaks are inevitable, but pandemics are optional.” But pandemics only remain optional if we have the will to disrupt our politics as readily as we disrupt nature and wildlife. In the end, there is no real mystery about the animal source of pandemics. It’s not some spiky scaled pangolin or furry flying bat. It’s populations of warm-blooded primates: The true animal source is us.”

These arguments push us to take collective responsibility for pandemics, as a human species, rather than the fragmented, competitive, anarchic scramble of each against all, blaming each other, we have witnessed as corona virus spread and spread further. The extent to which global co-operation has faded and failed, when most needed, is shocking. In the middle of the pandemic the UN called for real money for the poorest countries, to help them handle corona virus impacts. If this is news to you, it is because the UN plea got almost no media coverage at all.

The global “rules-based order” has turned out to be a fiction. Both the international “system” and effective regulation within China have been overwhelmed by greed, fear, panic, corruption and selfishness.

Is there any alternative to anarchy? One alternative is to bitterly blame it all on China and specifically on the CCP’s fatal determination, in the early weeks of infection, to hide all evidence of crisis. Anger only divides us all further, although some Tibetans see this as an opportunity to reclaim victim status, in a world of victims.

The Tibetan lamas do provide us with perspective, reminding us to have compassion for all and not delude ourselves that any of us is exempt from danger. Situ Rinpoche and Mingyur Rinpoche, among others, offer targeted heartfelt advice.

Rather than blaming, if we listen to voices from with the pandemic, within lockdown, we are better prepared as the virus comes closer and closer to us, wherever we live. That is why this blog began with a poet and a novelist in Wuhan, surrounded by confusion, isolation and infection.

So we turn to another voice from another novelist inside the epicentre, when it moved on to Rome. Francesca Melandri reminds us Italians did not listen to Wuhan voices and were not prepared physically or mentally when the full pandemic hit.

Maybe you should cue Messaien’s Quartet for the End of Time as you read what she writes to prepare us:

“I am writing to you from Italy which means I am writing from your future. We are now where you will be in a few days. The epidemic’s charts show us all entwined in a parallel dance.

We are but a few steps ahead of you in the path of time, just like Wuhan was a few weeks ahead of us. We watch you as you behave just as we did. You hold the same arguments we did until a short time ago, between those who still say, “it’s only a flu, why all the fuss?” and those who have already understood.

As we watch you from here, from your future, we know that many of you, as you were told to lock yourselves up into your homes, quoted Orwell, some even Hobbes. But soon you’ll be too busy for that.

You will miss your adult children like you never have before; the realisation that you have no idea when you will ever see them again will hit you like a punch in the chest.

Old resentments and falling-outs will seem irrelevant. You will call people you had sworn never to talk to ever again, so as to ask them: “How are you doing?” Many women will be beaten in their homes.

You will wonder what is happening to all those who can’t stay home because they don’t have one. You will feel vulnerable when going out shopping in the deserted streets, especially if you are a woman. You will ask yourselves if this is how societies collapse. Does it really happen so fast?

You will count all the things you do not need.

The true nature of the people around you will be revealed with total clarity. You will have confirmations and surprises.

People whom you had overlooked, instead, will turn out to be reassuring, generous, reliable, pragmatic and clairvoyant.

Many children will be conceived.

Elderly people will disobey you like rowdy teenagers: you’ll have to fight with them in order to forbid them from going out, to get infected and die.

You will try not to think about the lonely deaths inside the ICU.

You’ll want to cover with rose petals all medical workers’ steps.

You will be told that society is united in a communal effort, that you are all in the same boat. It will be true. This experience will change for good how you perceive yourself as an individual part of a larger whole.

If we turn our gaze to the more distant future, the future which is unknown both to you and to us too, we can only tell you this: when all of this is over, the world won’t be the same.”

ONE MORE VOICE FROM INSIDE LOCKDOWN

Our final voice from within virus lockdown is Tibetan poet Woeser in Beijing, February 2020, a double lockdown preventing her from being in Tibet, or out anywhere:

“But It Was This Time and This Place

I thought I had been through every type of circumstance

but I never expected

I would imprison myself for so long,

for so long. Yesterday the haze was thick outside my window

Today, it’s sunny for a thousand miles

The day before yesterday a blizzard

I look down from my upper story apartment

I look to the left, to the right

Of course, it’s not just me who has confined myself.

This world that has suddenly revealed its true form

Even the devil is powerless

and before I used to think it was all imaginary.

For example, I thought Kṣitigarbha’s descriptions of hell

were only to enlighten sentient beings, but it turns out they were of this time

and this place. What I thought before was simple falsehood.

“Give me your hand for a time. Hold on

to mine…. Squeeze hard. Time was we

thought we had time on our side.”

[1] Science, 27 MARCH 2020 • VOL 367 ISSUE 6485 p1435

Van Uhm, D. P. (2016a), The illegal wildlife trade: inside the world of poachers, smugglers and traders (studies of organized crime). New York: Springer.

Van Uhm, D. P. (2016b), ‘Illegal trade in wildlife and harms to the world’, in Spapens, A. C. M., White, R. and Huisman, W. eds., Environmental crime in transnational context. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.

Van Uhm, D. P. (2018a), ‘Talking about illegal business: approaching and interviewing poachers, smugglers, and traders’, in Moreto, W.D. ed., Wildlife Crime: From Theory to Practice. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Van Uhm, D. P. (2018b), ‘Wildlife and laundering: interaction between the under and upper world’, in Spapens T., White, R., Van Uhm, D.P. and Huisman, W. eds., Green crimes and dirty money. London: Routledge.

Van Uhm, D. P. (2018c) The social construction of the value of wildlife: A green cultural criminological perspective. Theoretical Criminology, 22(3), 384–401

Van Uhm, D. P., and Moreto, W. D. (2017), ‘Corruption within the illegal wildlife trade: a symbiotic and antithetical enterprise’, The British Journal of Criminology, azx032.

[2] Daan P. van Uhm and William D. Moreto, Corruption Within The Illegal Wildlife Trade:A Symbiotic And Antithetical Enterprise, British Journal of Criminology, (2018) 58, 864–885