Blog 3 of 3 on a big new hydro dam in Tibet

EAST-WEST NORTH-SOUTH THE PARTY IS LEADING EVERYTHING.

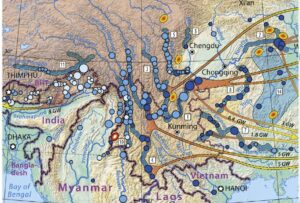

The intersectionality of Kham Markham is core. The magic of fungibility happens in Markham. Water turns into electricity, horses into tea, rivers into regional spheres of influence, movement is everything. China’s trajectory, from humiliation to hegemony, is a flow of accumulating strength.

Markham marks the intersection of flows, where the waters of Tibet flow from north to south, and electric energy flows from west to east. For centuries Markham was where Tibet meets China, for mutually profitable trade in wool, tea and horses, a flow which made Markham prosper. The Manchu Qing dynasty conquered China on horseback, and the Qing armies, over the following centuries needed wool from Tibet and the sturdy Tibetan horses for their exclusively Manchu army. The Tibetans needed the tea.

By modern standards the trails were precarious, those flows were minor, not conducive to sufficient accumulations of wealth to invest in modernity, far too many middlemen taking a cut. Markham was an entrepot, to be romanticised once the tea/horse trade was gone, but it had no place in the flows of modernity, on a greatly expanded scale.

The waters of Kham are destined by gravity for the sprawling Mekong delta of southern Vietnam. The energies of those flowing waters are destined by hubris for Guangdong, far to the east, where the flow of electricity meets the flow of ships bringing oil and minerals from all over the world. The result is the flow of capital. GDP is not, as people suppose, a quantum of money, it is a flow, intercepted at a moment, for measurement. Everything made in Guangdong, the world’s factory, then flows to Yiwu, the greatest showroom on earth, and out to the world, circling, circling. The waters of the Mekong push its delta out into the South China Sea, where it meets China’s Nine-Dash Line, completing the circle made in China.

Markham in the past prospered sufficiently to be a law unto itself, repelling the reach of the Lhasa based state, as well as colonisation by China.[1] Now it is no longer possible that the people of Markham stay static, puddling about on the riverbanks in their tiny mudwalled salt evaporation ponds, herding beasts to market, farming small plots at river bends to grow barley.

The times have changed, we are now in an era where everything moves quickly, everyone must flow, and Markham must become more than an extraction enclave where the heat of the sun, rush of the mountain river and turbulence of the monsoon winds all flow into the electricity grid. The Markham folk must also flow.

Markham was one of the first districts subjected to the 21st century policy of closing pastures and farm fields to move the locals out.[2] Outsiders depict this program negatively, as displacement, exclusion, exclosure, demobilisation. Yet in eyes of the party-state this is a lesson in dynamism, in learning to enter the ever-changing modern economy, its army of mobile workers staffing the factories where the world is made. It is the necessary, inevitable transition from passive to active, static to dynamic, isolation to globalisation.

Made in China may automate further yet, needing fewer workers and more electricity, which is why Huadian is confident its Markham Rongme/Rumei hydro dam, planned to start generating electricity in 2034, will be much needed. Such is the far-sighted dynamism of state capitalism.

China’s party-state presents itself as able to solve any and all problems, through vigorous interventions. So how could the folks of Markham just persist herding sheep, among the endless rows of solar panels? No-one is to be left behind, Xi Jinping says. The most direct way of ensuring unambitious, unaccumulative Tibetans kickstart their mojo is to tell them the land is expelling them, they have been rejected by their own pastures and farms.

The irony is that China depicts its appropriation of the voice of the land as a mobilisation of static Tibetans mired in contiguous, ineradicable poverty, for which the only solution is to exit their lands. Yet in the new villages of (re) settlement, there are few linkages to the wider economic flows, and not much to do, since it is forbidden to keep even just a few animals. Effectively this is a demobilisation of nomads who used to be highly mobile.

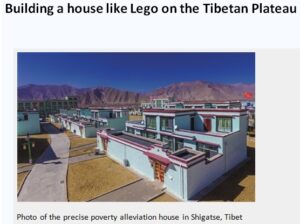

Further, this demobilisation concentrates Tibetan lives within the walls of mass manufactured prefabricated concrete panel houses bolted together, which requires trucking in the concrete panels, which are lightweight, because the concrete has been foamed. Injecting bubbles into thin panels while the concrete sets requires special techniques, as ordinary air bubbles will find a way to escape. To foam stable air bubbles into concrete requires use of protein foaming chemicals, the cheapest of which come from the wastes generated by China’s industrialisation of meat production. “Protein-based foaming agents come from animal proteins out of horn, blood, bones of cows, pigs and other remainders of animal carcasses. This leads not only to occasional variations in quality, due to the differing raw materials used in different batches, but also to a very intense stench of such foaming agents.”[3]

MAKE MORE MEAT

It is China’s national policy at the highest level to intensify beef and sheep muscle meat production, which emphasizes modern slaughterhouse procedures that generate huge amounts of waste organs, blood, bones and fat, which are not in demand by China’s urban middle class, who have the buying power. After industrial scale butchering, what to do with these wastes? This does not arise in traditional Tibetan livestock production, due to techniques which preserve and make use of all parts of an animal, leaving almost no wastes.[4] If an animal must die, use all of it.

Those nomad methods are now classified as inefficient. A 2021 policy decree from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs says: “due to the poor foundation of the meat, beef and sheep industry, long production cycle, backward farming methods, production development cannot meet the needs of rapid growth in consumption, beef and sheep meat supply is facing certain pressure. To promote high-quality and efficient development of meat, beef and sheep production, enhance the supply of beef and sheep meat security capacity, the development of this program.”

Yet again, the customary stewards of landscapes and livestock are deemed inadequate and inefficient, blaming them on one hand for endangering sustainability of grasslands, on the other hand for inadequate productivity. They might as well go, making room for industrial scaling up of intensive agribusiness, with faster turnover of livestock for slaughter. That is central to the five-year plan announced in 2021.

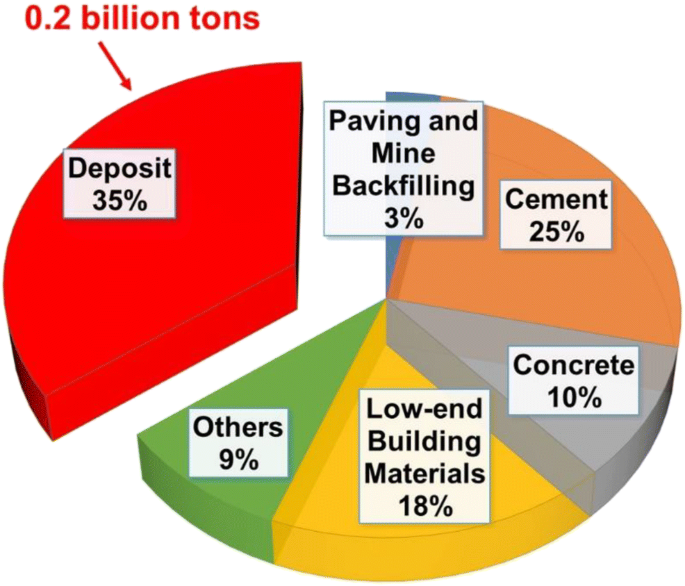

TIBET THE SOLUTION FOR CHINA’S WASTES

Modern production methods generate much waste. Coal-fired power stations generate fly ash, the particles extracted from combustion chimneys, in such quantities that China generates a half million tons of fly ash a year, for which it cannot find a use. Industrial animal slaughter generates waste of as much as half the weight of the beast slaughtered. What to do?

Both of these problems of industrial byproduct externalities find a happy solution in Tibet. The fly ash is used at mine sites in Tibet, in the hope of adding it to the tailings wastes left at the mine site after extraction and concentration of ores, in the hope that tailings plus fly ask will turn the wastes to concrete. The animal wastes are a cheap source of the proteins needed to ensure foamed concrete foams long enough for the concrete panels to set hard, making them much easier to transport all over Tibet, wherever possible. The only problem is the stench, which eventually dissipates.

![]() A leading manufacturer of synthetic foaming agents states: “Standard protein based foaming agents, are made with protein hydrolyzate from animal proteins out of horn, blood, bones of cows, pigs and other remainders of animal carcasses. This leads on the one hand to a very intense stench of such foaming agents on the other hand to a broad range of molecular weight of the proteins because the raw materials are always changing.”

A leading manufacturer of synthetic foaming agents states: “Standard protein based foaming agents, are made with protein hydrolyzate from animal proteins out of horn, blood, bones of cows, pigs and other remainders of animal carcasses. This leads on the one hand to a very intense stench of such foaming agents on the other hand to a broad range of molecular weight of the proteins because the raw materials are always changing.”

Requiring rural Tibetans expelled from their lands and herds to live in houses impregnated with blood and organs of the animals they used to tend, with respect for fellow sentient beings, is an odorous insult. It has become standard operating procedure, a further instance of Tibet becoming the solution to China’s problems.

This may be one reason why clearance of Tibetans from their lands around Markham has sought to empty landscapes and communities, more intensively than removing a quota of the locals. Yonten Nyima reports that “In the TAR, there have been two ongoing programmes of cross-municipality, whole-village resettlement. One, which started in 2018, involves the resettlement of farmers from two counties – Gonjo and Markham in Chamdo in eastern TAR – to Lhasa, Lhokha, Kongpo and Shigatse in central TAR.” The erasure, relocation and dispersal of entire communities 市整体易地, shì zhěngtǐ yì dì, is a radical policy so far implemented in only a few districts.

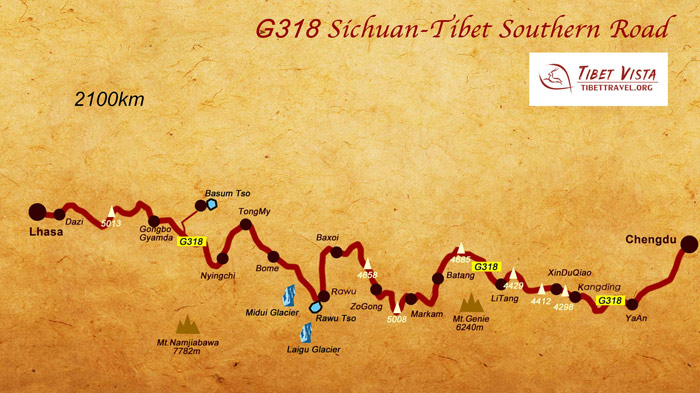

CHINA’S ROUTE 66

Solar and wind installations need a lot of land, which become sites of exemplary modernity, not for mingling with backward, unproductive wanderers. That implicit assumption applies to all of Markham, which is meant to be a frontier showpiece, where China and Tibet actually meet. The G318 highway stretches all the way from Shanghai to Markham, Lhasa and right to the Himalayan line of actual control on the border with India. This makes the G318 legendary, an east to west straight line that joins two worlds, in Markham. The G318 is as legendary, and as nation-building as America’s famous Route 66, built almost a century ago.

On the last day of 2020, pandemic lockdowns notwithstanding, the expensively upgraded G318 expressway, from Wenchuan (Lunggu in Tibetan), at the foot of the Tibetan Plateau, all the way to Markham (Garthok in Tibetan), was formally opened to traffic, four lanes, lots of showy big metro cloverleaf on ramp interchanges, an expressway with the lot. The Sichuan 2021 Transport Yearbook was mighty pleased.

With reason. The way has been made smooth, other than the tollbooth stops to pay to use. Mountains have been tunnelled, river valleys bridged, a virtuoso display of China’s engineering mastery. Distance and time have contracted, Tibet is brought closer to China. For Han. The usual security state roadblocks immobilising Tibetans from freely travelling Tibet still apply.

Markham/Garthok is as surely the entry to another world as is Khorgos, far to the north, where long-haul trucks and trains transit from Xinjiang to Kazakhstan. Markham is the limen, the water margin, the tea and horse route reborn for tourist consumption.

For Han self drive motorists doing the heroic conquest of Tibet in person, the romance has gone. The old two lane G318, like Route 66, was not only where a man could get his kicks, but well worth dash camming and posting online. But for everyone else, Tibet is now enticingly yet safely and smoothly close by. It is now possible to drive from Chengdu via Ya’an, Luding and Wenchuan all the way to the Markham portal to Tibet (although from Wenchuan/Lunggu on is actually Tibetan). Google Maps says you can do the 318 kms uphill drive in 4.5 hours, from one world to another. Tempting.

This is not the only expressway spearing into eastern Tibet from China’s lowlands. Mountains and rivers make way for the high speed railway and motor expressway from Lijiang up to Dechen, where so many hydro dams have been built.

HIGHWAY TO THE HIGHLANDS

China has taken Tibet on an accelerated trajectory into modernity and globalisation. In the 1950s, as the People’s Liberation Army marched in on foot, the artillery that utterly outgunned Tibetan resistance was hauled overland by yaks commandeered by the PLA who, in the absence of motorable roads, did forced marches in order to ambush retreating Tibetans, often with their herds, on the tracks of customary trade and pilgrimage routes. While the Tibetans moved slowly, at the pace of yaks pausing to graze, the soldiers slaughtered exhausted yaks, to maintain the pace of their advance. Markham and nearby Batang were centres of greatest resistance, and greatest slaughter of Tibetans.[5]

Once it became clear that Tibetans, specially in Kham, rejected China’s “liberation”, road-building became top priority. Premier Zhou En-lai issued lengthy instructions in 1956, focussed specifically on Kandze, the Tibetan prefecture of Sichuan that provides access to Markham and all of central Tibet.[6] Since the purpose of Zhou’s orders were to ready all of Tibet for compulsory class warfare (known in CCP phrasing as “democratic reform”), a necessary precondition was a road network capable of moving soldiers and weapons to wherever uprisings would occur. Thousands of landless rural Chinese were sent to do the construction work.

Roads are the core technology enabling modern nation-states to grasp what they reach for. Despite constant investment in upgrading road and rail access to Tibet, until now the long road from the north, from Lanzhou and Xining, via Gormo, to Lhasa remains the main artery of modernity with Chinese characteristics. Only now is fast, reliable access to Tibet from Chengdu fast shaping up as the new linkage that binds Tibet to China as never before. Before this decade is out, there will be a double tracked, electrified railway all the way from Chengdu to Lhasa, with countless tunnels and bridges; and with a similarly smooth expressway for road haulage.

CLOSING RIVERS, CLOSING MINDS

China’s hydropower politics debates were among the first to be closed down by Xi Jinping’s ascent. Today, it is hard to imagine the remaining Tibetans of Markham successfully objecting to the damming of their Za Chu, plus the colonisation of their farmland and pastures by mass solar arrays, wind turbines, power grids and perhaps pumped hydro.

As recently as a decade ago, local communities did mobilise against hydro dam projects, drawing in elite allies well-connected in Beijing, better placed to speak truth to power. They took many risks, contradicting the plans and projects of an authoritarian state, but sometimes they succeeded, including on the Nu river not far below its Tibetan upper reaches. Political scientists such as Andrew C Mertha wrote admiringly and at length on these courageous campaigners -he called them water warriors- who skilfully challenged China’s hydraulic power politics.[1]

Yet by 2014, only two years into Xi Jinping’s new era, environmental NGOs banded together to publish what they prophetically called The Last Report on China’s rivers and hydro dams. What made it their last report was their clear signal that they were being coercively silenced, excluded from the public sphere, as were feminists, dissenting artists, human rights defenders, and any corner of civil society that expressed views that are the sole prerogative of the party-state.

A decade ago it was difficult for China’s subalterns to speak, but not impossible, especially if they managed to create informal coalitions that included a few influential Beijing-based elite scientists, who agreed with them the dams on wild rivers needed a rethink.

Now the Last Report is long gone, and cadres working for local government know they will be punished if local protests reach the ears of county officials or, much worse, the ears of provincial and national party-state nomenklatura.

So the Rongme/Rumei dam, surrounded by photovoltaics, wind turbines and power grids shall proceed, without overt opposition, in a county where wholesale removal of local communities has been implemented since 2018. Mertha’s case studies of communities in Sichuan campaigning against hydropower are of a vanished era. Allowing dissenting voices is intolerable in a new era where everything is seen as risky, in need of control and securitisation.

The dam, or more probably a new cascade of dams, will go ahead. The National Development and Reform Commission has so decreed, and allocated funding. The secrecy as to exactly where in Tibet (Autonomous Region) the new dam/s are located is a further symptom of the extreme centralisation of planning, power and knowledge in the Xi Jinping era.

There are four further reasons why the Khampa of eastern Tibet will find it hard to counter this menu of green colonialist incursions. First, Kham is split into no less than four provinces, with Khampa Tibetan prefectures in Sichuan (Kandze), in Qinghai (Yushu), in Yunnan (Dechen) and in Tibet Autonomous Region (Chamdo).

Second, Kham is the biodiversity hotspot of China, its steep valleys a short traverse from subtropical up to arctic, on each slope, yet vey little is set aside as officially protected areas, where development is restricted.

Third, even UNESCO World Heritage designation does not prevent China from building hydro dams within the Three Parallel Rivers World Heritage site.

FOR DISPLACING TIBETANS EVERYONE GETS A CUT

It is the fourth reason that perhaps is the most decisive, because it is embedded in the inner workings of the party-state under Xi Jinping. Xi is credited with having cracked down hard on corruption. Even if the campaigns of purification and rectification selectively targeted factions of his rivals, he is praised, in China and beyond, with having ruthlessly eliminated the capture of state funds meant for poverty alleviation and environmental remediation to the pockets of well connected cadres who instead use the money to buy apartments and pay their concubines.

However, corruption remains deeply entrenched, and there are reasons why much state capture is ignored. This is explained in precise detail, in a book by Ben Hillman, a political scientist who immersed for years in fieldwork among the cadres in charge of hydro dams, poverty alleviation and community resettlement programs on the fringes of Tibet. Hillman, fluent in Chinese, won the confidence of county level cadres who were frank about how the system operates, on condition their location be disguised. Hillman obliges. This means his informants are frank, likewise the author bringing us the story told in Patronage and Power: Local state networks and party-state resilience in rural China.[2]

Hillman may not be the first to name the deeply embedded exclusive networks that capture central funding and divert it to their enrichment, networks of “iron brothers” who know they can trust each other because together they all accumulate wealth, on their own they cannot. Whatever their rank, whatever ministry or party organ employs them, if they spend enough time outmanoeuvring rival factions, and bending state funded projects to their will, they will succeed. Hillman, however, describes these manoeuvres from the inside, and the reasons Beijing tolerates it. As long as central are seen to be delivering what they announced, and as long as local cabals are no threat to higher level factions, there is tacit acceptance that this is how things get done, and always has been.

The losers are powerless. Losers are the villages at the end of the new road that falls apart in the next monsoon because far less expensive asphalt than specified was used to seal the road. Losers are ethnic minorities, especially in the Tibetan borderlands where Hillman worked, who fail to qualify for microcredit loans diverted to factional buddies, who are displaced by hydro dams and provided only minimal compensation, villagers relocated to new villages of substandard prefab concrete panels, into housing that is shoddily bolted together, with no space for traditional livelihoods.

As long as the party-state can tell China and the world it has benevolently provided the remote, backward and poor with sealed roads to access markets, built schools and clinics, loaned startup capital to ethnic entrepreneurs, moved the contiguous poor to new districts where they can prosper, built irrigation channels for poor farmers, all is well, and no-one can or would dare say the emperor is naked. Hillman describes many such projects, and details the ways money was diverted from intended use, to enrich factional insiders.

Hillman’s fieldwork was just before Xi Jinping took command, and a repeat immersion in local state capture would be impossible now. Have Xi’s disciplinary rectification campaigns rooted out these local bosses? While investigation is no longer possible, there is no reason to suppose, at local level, that much has changed. Why would it? No outside scrutiny is possible, and no indigenous protest by the Hui, Naxi, Yi, Nuosu and Tibetan villagers where Hillman worked will be tolerated.

Perhaps some of the more flagrant abuses are less likely now, when the party’s Central Discipline Commission is no longer seduced by being wined and dined in the county town, and then fail to do a real inspection. Hillman tells how a small hydropower station for local villagers was successfully built on paper, but not in reality. “In due course Laxiang County’s Hydroelectricity Bureau reported that the hydropower station was completed as planned, but claimed it was subsequently destroyed by a landslide. When I visited the township in 2011, local farmers informed me that no such landslide ever occurred and no power station was ever built.”[3] Laxiang is a fictional name.

Those farmers are now worse off than before. Officially they do have hydropower, their poverty and backwardness has been alleviated, they should publicly express their gratitude, and their productivity as measured in annual statistics, should increase.

Hillman reminds us that whether cadres rip off the locals, or cultivate their support, either way villagers are powerless, and the cadre promotion system pays no heed to local opinion. Nonetheless, he says, most cadres do cultivate a good reputation among villagers, since they are kin. But what happens when cadres are of the Han supermajority, with authority over villages of minority nationalities? This is where it is not only possible that villagers are treated as chives, to be harvested at any time, such predatory extraction is the norm, known simply as the peasant burden, nongmin fudan.

Exploitation of Tibetans and other minority ethnicities is routine. If the cadres, or at least some of them, are Tibetan, there may be channels for discreetly pressing for justice. But the entire system, top to bottom, disempowers and silences Tibetans, and quickly classifies any protest as criminal, to be dealt with decisively by calling in the police.

These are the settings in which a new hydro/solar/windpower base is to be built in Tibet. It is no accident that none of the official announcements and media coverage name the specific location. Why alert people who may object?

[1] Andrew C Mertha, China’s Water Warriors: Citizen action and policy change, Columbia, 2010

[2] Stanford, 2014,, especially ch 5.

[3] Hillman, Patronage and Power, 125

BIG IMPACT, MODEST OUTPUT

Despite the extensive land appropriation, construction expense, and long lead time, this dam/solar/wind complex will deliver nowhere near Li Peng’s Three Gorges, nor make it into the world top 50 hydro dams. Its’ generating power will be only one third of the biggest dam Huaneng has built, further down the Lancang/Mekong, known as Nuozhadu. Yet Huaneng’s capacity to command premium prices will ensure profitability. The installed electricity generating capacity will be 2.6 million kilowatts, yet actual output in kilowatt hours of produced electricity at 11.3 billion kwh. This is because for at least six months of the year river flow is low, partly balanced by stronger sunshine. It is in the summer monsoon season that the winds blow and rivers flow; in the winter the sun shines. This may increase the land area taken for solar array, in an effort to equalise production.

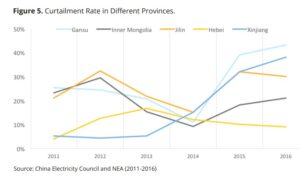

However, unless the central party-state forces provinces to take all the electricity exported from Tibet, much will be wasted, as has happened repeatedly in recent years. This is especially likely if Huaneng charges high prices. Provincial governments which own and operate coal-fired power stations, as many do, prefer their own inhouse revenue sources, and have frequently refused to connect to the expensive cross country grids, made of copper from Tibet. Officially this is called electricity abandonment or curtailment.

Central leaders want to be seen to be moving away from coal, and into “green” energy. There have been several blunt demands that provinces reluctant to take their electricity from way out west, including Tibet, must now do so. Yet abandonment persists. Local governments have plenty of practice in saluting when Beijing issues a proclamation, then ignoring it.

In Guangdong however, by the time the 11-year construction period is completed, it will be 2034 and the world’s factory may be in much need of power. But that power needs to be available when industry needs it, hard to guarantee when rivers, winds and sunshine naturally rise and fall. Could this mean a cascade of dams, pumping water up as well as down, to match supply with demand?

2030 is the year China has pledged to BEGIN at last reducing carbon emissions, long after other major emitters. China is credited with taking the high ground. Huaneng’s Markham dam will be represented as the clean alternative. Who knows how much electricity Guangdong will need from 2034 and beyond? Build it and they will switch on?

An old Tibetan proverb: When the wise make an error/it’s off by six feet,

When the fool makes an error/ it’s off by a handspan.

[1] Andreas Gruschke, The Cultural Monuments of Tibet’s Outer Provinces: Kham, vol 1, White Lotus, 2004, 152

[2] Yonten Nyima, ‘When the Land Cannot Support the People Any More’: The Utility of an Official Formulation in Resettlement in Tibet, Inner Asia 25 (2023) 79–90

[3]Ali Hamad, Materials, Production, Properties and Application of Aerated Lightweight Concrete: Review, International Journal of Materials Science and Engineering Vol. 2, No. 2 December 2014

[4] Hoshi Izumi, Dictionary of Tibetan Pastoralism, Tokyo Univeity of Foreign Studies 2020.

[5] Carole McGranahan, Arrested Histories, Duke Press, 2010, 76, 78, 275

[6] Melvyn Goldstein, A History of Modern Tibet, vol 3, U California Press, 2014, 263