Blog 2 of 3 on a big new hydro dam in Tibet

Migrating China’s massive energy extraction infrastructure industry far upstream into Tibet has long been signalled by party-state planners. Potential dam locations have been mapped by engineers for decades, and listed as potential dams in official plan decrees. Yet most of the big dams have been built so far just below Tibet, where access is easier, stream flows bigger and workforces not required to endure Tibetan winters, which make concrete setting quite tricky.

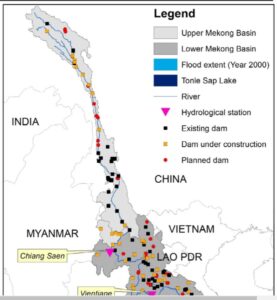

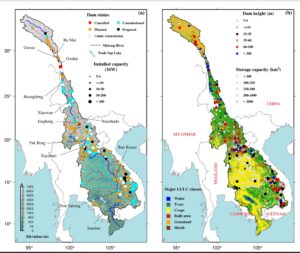

There is a cascade of nine big stepwise dams on the upper Ma Chu/Yellow River in Amdo/Qinghai, and a cascade on the Yarlung Tsangpo/Brahmaputra, and dams on the Za Chu/Lancang/Mekong in Dechen Autonomous Prefecture in Yunnan.

Thus far the uppermost Za Chu and Dri Chu/Yangtze have been spared major dams far upriver, in Tibetan heartland.

So Huaneng’s great leap upwards is a major colonising inroad, a substantial pushback of the frontier, intended to create “China’s Tibet” as ground truth.

This might seem a lot to hang on a dam which by design is not one of the biggest. However, the dam, given its long lead time, is part of a much bigger package designed to firmly imprint a much larger area as China’s, exclusively.

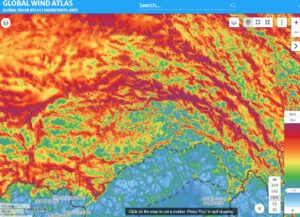

The package of solar, wind power, hydro, power grids and perhaps pumped hydro with multiple dams, adds up to much more than the stated 2.6 million kilowatts of generating capacity, and actual output in kilowatt hours of produced electricity of 11.3 billion kwh. CCP media Global Times says “According to the plan, the clean energy base has total hydro and solar power generation capacity of 20 million kilowatts and it can transmit 57.1 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity to the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area each year. The clean energy base will start each phase of construction gradually during the 14th Five-Year Plan period (2021-25). It will be put into operation in 2030 and completed in 2035, according to the plan.”

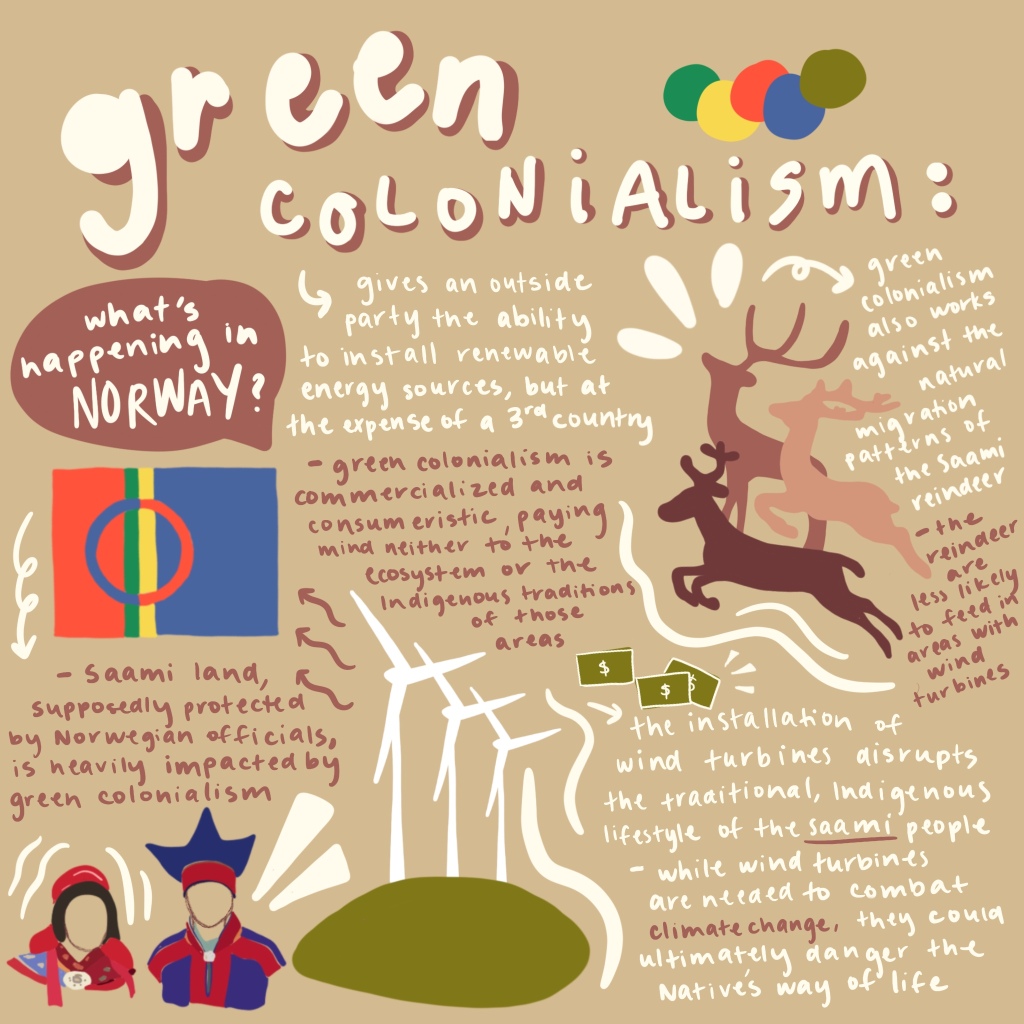

This is a new approach, an integrated suite of green colonialist incursions not seen before. In recent years solar arrays have been added to boost nearby hydro dams already built, but now solar, hydro, wind and grids are bundled from the outset.

The planned result is that total generating capacity will be 7.7 times what the Rongme/Rumei dam is designed to produce, and actual output sent to Guangdong will five times greater than the dam output.

SOLARIZATION

Taken together this is a massive project, with solar dominant. This is the solarization of Tibet.[1]

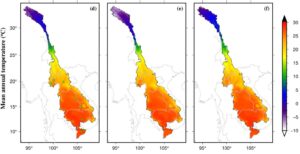

Solar will dominate in various ways. First, the big drawback of hydropower, on all Tibetan rivers, is the reliance on the few months of monsoon rains in summer, which means low streamflow for at least six months a year, even when year-round glacier melt provides year-round stream flow. Since the sun shines more outside the cloudy monsoon season, China’s hope is that the combination of hydro and solar will balance out.

Secondly, solar is much quicker and cheaper to build, as long as sufficient landscape is available. Scheduled timing for the new dam to start generating is 2034, but Global Times says much of the whole package can start building in the current Five-Year Plan period which ends 2025, and be fully operational by 2030, well ahead of the dam. That’s solarization, the sterilization of the land, getting rid of all Tibetans, preparing the soil for the implantation of solar modernity with Chinese characteristics.

China calls this solar/hydro/wind package a base. China does love a good base; it connotes security, reliability and elevates a project to national importance. Fifty and more years ago the shores of Tso Ngonpo, Tibet’s biggest lake, were a military industrial base for making nuclear weapons. Before that the retreating communist armies established a base in Yan’an, now a red tourism pilgrimage site.

SOLARIZATION TO RECLAIM THE WASTE LAND

In order for a base to be secure, it must first be purged of all competing land uses, especially if the users can claim prior occupancy. In order to sterilize/solarize landscapes designated as bases, they must be reclassified as waste lands, a negative label for land that has no human use, and much needs to become humanly useful. This is a necessary step in the solarization process, because the party-state seeks to avoid solar arrays being installed on large swaths of arable land, hence Tibet is the obvious location for large scale solar. It is “waste” land that is to be “reclaimed”; that is China’s customary classification system.

This distinction between arable and waste land is so important, a recent decree commands all levels of government “do a good job of photovoltaic power generation industry development planning and the convergence of land spatial planning. All places should seriously do a good job of green energy development planning and the convergence of land spatial planning, optimize the spatial layout of large photovoltaic bases and photovoltaic power generation projects. Encourage the use of unused land and the stock of construction land to develop photovoltaic power generation industry. Under the premise of strict ecological protection, encourage the construction of large photovoltaic base in the desert, Gobi, desert and other regional sites; promote the construction of non-cultivated land areas planning photovoltaic base. Project site selection should avoid arable land, ecological protection red line, historical and cultural protection line, special natural landscape value and cultural marker area, natural forest land, national sandy land sealing protection zone (PV power generation project output line is allowed to cross the national sandy land sealing protection zone), etc.; involving nature reserves, should also comply with the relevant regulations and policy requirements of nature reserves.”

This March 2023 decree from the Ministry of Natural Resources goes further, insisting that if regulations on poverty alleviation clash with this Notice, this Notice shall prevail.

Senior party officials are now urging many such solar/wind/hydro bases be set up across Tibet: “This is very important for fully exploiting the potential and low-carbon advantages of wind and solar power resources in the northwest region, significantly improving the carbon reduction and added value of hydropower resources in the southwest region, and then enabling the western region of China to take the lead in realizing the dual carbon goals and promoting the formation of a new pattern of western development.”

LEARNING FROM WUNONLONG

Currently the highest completed and operating dam on the upper Lancang/Za Chu/Mekong is Wunonglong, completed in 2018. The dam wall is 138 m high. The further upriver you go, the steeper the terrain, the higher the dam wall.

We know a lot about the Wunonglong dam, all made available in the close monitoring portal of the Stimson Centre, which provides a fortnightly sat map and tracks the fluctuating dam levels, with further links to more. Wunonglong is in Yunnan, well south of Tibet Autonomous Region and the first 1000 kms of the uppermost Lancang/Mekong/Za Chu.

So Huaneng’s latest dam, in Tibet, is much further upriver, at a higher altitude. Usually the higher the location, the smaller the area dammable, because the valley walls are so steep. That means less water is stored, less is available to generate electricity, less bang for the buck, diminishing returns. But Huaneng is pressing on; its’ business case is made by its’ red gene princeling connections, not by its volume of impounded water.

In the existing cascade of 11 hydro dams on the upper Lancang, only two capture large amounts of water every summer monsoon. The six existing dams above the massive Xiaowan add very little to water retention; all they do is seasonally spin the turbines. The same will be true for Huaneng’s latest. China’s hydro dams usually block fish migrating upstream to reproduce, in mountainous areas dams often silt up as fast water flow is slowed, and the sheer weight of impounded silt and water can trigger earthquakes. Climate change means some years are drought years, and river flow drops greatly. These are strong reasons for switching to cheaper, more versatile and flexible solar and wind power.

Rongme/Rumei is in an even better location, right at the junction of the east-west G318 trunk highway, and the 214 headed south. All factors of production are available, including ready access to equipment and labour markets of the Sichuan basin, which includes mega cities Chengdu and Chongqing. So Rongme/Rumei, in Markham 马尔康county seems the likeliest. Rongme/Rumei’s output, as defined by CGIAR years ago, and by the 2023 Huaneng go-ahead announcement, closely match, both in installed turbine generation capacity, and in actual annual production, with the 2023 numbers slightly more ambitious.

For China, Rongme/Rumei is in Tibet (Autonomous Region), but from a Tibetan perspective a much wider area is Tibetan, and is defined so by China at prefectural level. Since Kham is fragmented into four provinces, the dam builders are focussing Dechen Tibetan prefecture of Yunnan, where Huaneng has already built two hydro dams, and nearby to the east, Kandze Tibetan prefecture of Sichuan. Chamdo Tibetan prefecture of TAR, which includes Rongme is actually the most recent of these three portions of Kham to be awarded modernity with Chinese characteristics, and without choice.

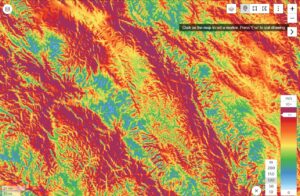

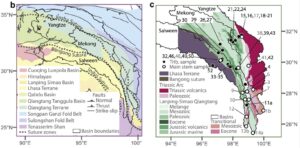

Despite these muddled mappings, which are a legacy of successive Chinese invasions, on the ground there is a coherent, even compelling, topography. This is the land of the four rivers and the six mountain ranges that flank them. All the rivers and ranges here run in parallel, at the forefront of Tibet’s tectonic push into China. To Tibetans this is Chushi Gangdrug, literally four rivers and six ranges, with the Mekong/Lancang/Za Chu only 60 kms to the east of another major river, the Salween/Gyalmo Ngulchu; with the Yangtze/Dri Chu a further 60 kms east, all running parallel, separated by snow mountains. Everything in this dramatically uplifted and deeply dissected land runs from NNW to SSE, while the monsoon rains flow in upriver in summer up the valleys.

The old Tibetan trading caravan route precariously bisected this rugged landscape, plunging up and down again and again, to provide lowland China with sturdy Tibetan ponies, and bring back the brick tea of Yunnan.

China now defies the north-south tilt of the mountains and the rivers, to turn eastern Tibet to directly face the east, achievable only through tunnelling and bridging, to bring expressway toll roads, high speed railways into Tibet from the east, and hydro power generated electricity out eastward. Reorienting Tibet into China is a massive undertaking, which is nearing activation only after 70 years of colonising occupation.

Three of the world’s great rivers running in parallel, only 60 kms apart, with massive mountain chains in between, made for a UNESCO World Heritage site, a tourism magnet branding China sought, and gained in 2003 from the UN. One might suppose the inscription of the Three Parallel Rivers as UNESCO World Heritage might prevent hydro dam construction, but China mapped the site boundaries to exclude the actual rivers that name the site, which has left UNESCO powerless to prevent the industrialisation of this natural wonder. China brushes aside repeated protests by UNESCO scientific missions, as none of their business. The result is a patchwork park, territorialised to fulfil China’s primary aim, of boosting tourism numbers. The irretrievable result of the mistake of 2003 is a huge World Heritage area, of 900,000 hectares, yet broken into 15 separate parcels of land, with the actual rivers that give the whole property its name entirely excluded.

Hydro damming is integral to China’s program of reprogramming Tibetan minds and lives. A big hydro dam exactly where China’s thrust westward meets Tibetan rivers headed southward, is part of the whole-of-government co-ordinated strategy of the Tibetwork Forums that guide all aspects of China’s nation-building in Tibet.

LOGICS OF COLONISATION

The European overseas empires built ports, to connect the colony with the distant metropole. China’s contiguous empire builds railways, expressways, hydro/solar/wind arrays feeding electricity far to the east through power grids delivering a million volts, far bigger than any power line you’ve seen.

Not only are transport, energy and economy co-ordinated to make Kham irrevocably Chinese, so too the centralised education system delivering the inexorable agenda of assimilation, and the program of removing entire upland communities to relocation villages hundreds of kilometres away, are all elements in the policy package. This top-level integration of inscribing Chinese characteristics in all aspects of land and lives in eastern Tibet is seldom recognised as a coherent whole. Education, poverty alleviation, biodiversity protection, water security, rural rejuvenation, housing, prosperity, vocational education, urbanisation are usually viewed separately, but China is now much more ambitious than the port builders of Calcutta, Lagos or Luanda.

In the schools of Markham, where the Tibetan mother tongue is relegated to a vestigial remnant irrelevant to modernity, on the river bends where Tibetan farmers plant abundant crops, on the pasture lands where cattle and horses flourish on alpine meadow profusion, the same suite of insistent, coercive policies are enforced. The removal of entire communities to resettlement far from their lands and land tenure security, to be replaced by wind turbines, solar arrays, hydro dams and power grids, are inseparable aspects of making Kham Chinese. Making watersheds into powersheds, displacing and dispersing local communities, who had a thousand uses for their lands, is how colonisers extend their reach.

The British in India, the Belgians in Congo, the Portuguese in Angola were never this ambitious. Like the Europeans, the Han Chinese find their colony in Tibet unsuited to mass migration, making it a settler colony. Like the Europeans, Chinese colonisers want the colony to pay its way, with hydropower the biggest profit in prospect. Unlike the Europeans China is determined to make the Tibetans Chinese, to assimilate Tibetan identity and mode of production to Chinese norms. This is one of the most penetrating agendas to be found worldwide, to make China hegemonic in all aspects of life.

A CLOSER LOOK

Where is this big new hydro dam in Tibet which Huaneng announced in May 2023 without bothering to name the location? An authoritative source identifying the many planned dams on the uppermost Za Chu/Lancang/Mekong is a team of nine scientists, from the Key Laboratory of Water Cycle and Related Land Surface Processes, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, and from Michigan universities, who in 2023 published in an open access journal a detailed map.[2]

This team maps the entire Mekong, unlike most mapped reports which don’t bother to include the uppermost riparian watershed, in Tibet, stretching right across Kham. When uppermost Mekong -routinely omitted by Asian Development Bank and Mekong River Commission- swims into view, we get granular detail, and the big picture. In overview, the Za Chu/Lancang/Mekong watershed is a bit like a human, with a head, a neck and a body. The body is the basin, spread out through Southeast Asia, the narrow neck is the river held tight by the mountains of Yunnan, and the head is the headwaters, with several tributaries feeding in to uppermost Za Chu as it makes its way across the hilly pasturelands of Kham..

For decades the Asian Development Bank has financed and run its Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) program, of busily connecting the Mekong countries to each other, by highways, railways and power grids, but in all GMS maps the Mekong is headless.[3] Tibet is missing altogether. When the head is included, it is clear what makes the river special. Basin communities of the lowlands cannot know what is coming downriver to them unless they know what is happening in the headwaters. The climatic transition from uplands to lowlands begins with a head wrapped in clouds, in the cold of glacial Tibet, which slows the steady release of snow and rain, making available river flow all year, even though the entire Mekong, top to toe, is in a highly monsoonal zone, where nearly all rain is in just a few summer months. Tibet matters.

The altitude of Tibet means the Za Chu/Lancang erodes deep valleys, as a mountain river cutting its way through a still-rising plateau. That makes for huge amounts of sediment in a powerful river, that in dam-free days made its way all the way down to the flat plains of Indochina, where it regularly replenished the fertility of the soil of millions of farmers. Now China’s hydro dams on the Za Chu/Lancang trap not only water but sediment as well, as river flow slows, silting up the dams, depriving the lowland farmers below of fertility. Ignore Tibet and loss of livelihoods is inexplicable.

The head of the Za Chu is now dotted, on the scientists’ maps, with 12 planned dam sites, of which only two, as of 2023, have actually been built, and two under construction, all small or medium-sized, for supplying electricity locally. But where the head narrows to a neck is the Rongme/Rumei 如美镇 (in Tibetan Rongme རོང་སྨད་) dam, also listed as under construction, a dam whose specifications closely match what Huaneng has announced.

The head of the Za Chu is now dotted, on the scientists’ maps, with 12 planned dam sites, of which only two, as of 2023, have actually been built, and two under construction, all small or medium-sized, for supplying electricity locally. But where the head narrows to a neck is the Rongme/Rumei 如美镇 (in Tibetan Rongme རོང་སྨད་) dam, also listed as under construction, a dam whose specifications closely match what Huaneng has announced.

Rongme/Rumei is a township of Markham county, where China’s main east-west national highway G318 runs alongside the Za Chu for a few kilometres, which makes for easy engineering access to the dam site, which can be seen above the pin on this map, as the maze of white lines of site access roads. Not to be confused with Rongde, on the nearby Dri Chu/Yangtze, in Sichuan, near Batang, even higher upriver, where more dam building is under way.

The Michigan science team classify Markham Rongme/Rumei as being under construction, with another large storage dam likely immediately upriver. This planned dam is mapped as a blue star, signifying it is designed to store more than 1000 cubic kilometres of water, and the dam wall is more than 100 m high. If these two dams are close, it may be that they are now designed to work in tandem, as a pumped storage system intended to supply intense bursts of electricity during peak hours, all the way to Guangdong. Outside of peak hours the turbines would generate just enough electricity to pump water back up to the upper reservoir, ready to rush down again in peak electricity demand hours in metro Guangdong.

This twinning of dams to make a pumped hydro system messes with river flow even more than standard hydro. For years downriver communities on the Mekong have complained that China’s many dams in Yunnan interrupt natural environmental flows and disrupt livelihoods built over many centuries on seasonal rhythms of a great river. Those dams in Yunnan are designed to hold back as much water as possible during the rainy summer, to extend the power generating period as long as possible, adding weeks and months to power output. As a result, water is released from impoundment slower, and longer, quite unnaturally.

PUMPED HYDRO?

But pumped hydro pumps up the speed of man-made river rises and falls, from monthly to hourly. Maximum disruption.

Pumped hydro is making a comeback as the way of balancing the variability of wind and solar power, by effectively turning rivers into giant batteries that store pent up water during low demand hours, then releases it in high demand hours, in the distant destination of the ultra-high voltage direct current power grid.

Such grids are expensive to build, not only because of the great distance between production and consumption, but also because the only way of transmitting electricity over great distances is by converting alternating current to direct current (AC/DC), which requires enormous, imported, expensive transformers, at both ends, to convert AC to DC and then, at destination DC back to AC.

These are reasons why, in the new “green energy” world, the wind power, solar power, hydro power and power grids are a package, ideally close to each other, which reduces the amount of copper wiring, and enhances the flexibility of juggling back and forth between energy sources. So the dams planned and proposed for the head of the Za Chu/Lancang/Mekong need much more land nearby, for the solar and wind farms, with much greater impact on local Tibetan communities. When a river functions as a battery, the energy it stores for a few hours, until needed, comes from the nearby wind and solar generators. That’s the deal.

DEPOPULATING POWERSHED LANDSCAPES

Can Tibetan nomads be trusted to continue their aimless wanderings, with their animals, amid the solar panels and wind turbines? That is how China frames it. For Chinese leaders, it is not a good look to have illiterate rural labourers (as China classifies drokpa in its official statistical yearbooks) wandering around the high tech that makes China proud, able to sell these technologies globally, with Tibet a showroom displaying China’s tech capabilities.

In elite Chinese eyes this is an obvious contradiction, that necessitates a decisive intervention. On one hand China manifests its mastery of heaven and earth by constructing the wind and water turbines, the solar arrays and the power grids. China is the global champion of green high tech. On the other hand, those rural labourers wander, fatalistically relying on heaven to provide. This is a key concept, in much use. Relying on heaven , 告别了守着黄河靠天吃饭的日子, gàobiéle shǒuzhe huánghé kào tiān chīfàn de rìzi. རྨ་ཆུ་བསྲུངས་ཏེ་གནམ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས་འཚོ་ཐབས་བྱེད་པའི་ཉིན་མོ་དང་ཁ་གྱེས་པ། literally: passively watching the river slide by without extraction, passively reliant on what the heavens provide.

This is the fate of backward, uncivilised and/or lazy people who passively wait for nature to produce all that is needful in life, to be gathered in season. In Chinese eyes, this gatherer lifeworld is little better than that of animals, and fails to show mastery of nature. At best this is a fatalistic resignation to subsistence economy 自给自足经济 zì jǐ zìzú jīngjì, utterly lacking in civilisation. This passivity is a horrifying weakness, 处于被动适应自然条件 chǔyú bèidòng shìyìng zìrán tiáojiàn, a passive acceptance of natural conditions.

What to do with those who rely on heaven? Since they show no initiative to improve themselves, they must be moved on, to enter history, modernity, development and urbanisation, rehoused in the new xiaokang moderate prosperity villages being assembled all over Tibet.

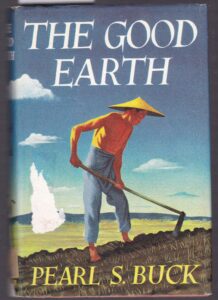

THE GOOD EARTH EXPELS YOU

To resolve the contradiction, a formula is required; a phrase that can be repeated endlessly as explanation of why Tibetan pastoralists must be dispossessed of their lands and land tenure security. The key phrase is 一方水土养活不了一方人yifang shuitu yanghuo buliao yifangren meaning literally, ‘the soil and water of a place cannot support the local people.’

This phrase is deployed by cadres inspecting local communities, to make it clear that the time of displacement, dispossession and demobilisation has arrived, and the only choice open to those who rely on heaven, is to assent to their removal.

This phrase is deployed globally in China’s official propaganda, mixed with scientific jargon of carrying capacity, stocking rates, land degradation, biomass growth rates and more. By adopting this voice, the party-state speaks for the land, becomes the voice of the land, which gives it ultimate authority to impose force majeure. This key phrase establishes the state as not only the owner of all rural land, but it becomes the incarnation of the needs and imperatives of the land itself. No-one can argue with that. The earth has spoken. The river has spoken: you must leave. The state is a ventriloquist; its’ message is cruelly dismissive. Your time, on your land, is over.

It is the land and the rivers that are expelling the people, unable to further bear the damage done by the locals, who have customarily understood themselves to be the guardians and stewards of the landscapes they graze, taking care to always move on well before overgrazing compromises sward health. Farmers and livestock producers across China, inheriting millennia of sustainable land use have a classic saying, which this new slogan reverses. For centuries rural Chinese have represented their harmony with nature with a proverb to be found also in school textbooks: 一方水土养活一方人, yifang shuitu yanghuo yifangren, the soil and water of a place support the people of that place. It is the insertion of buliao, cannot, that reverses the polarity of this familiar, comforting metaphor.

No-one can refuse. If the landscape you inherited from your family and clan turns against you, you cannot ask it to rethink. Through the agency of the cadres, and with the backup of the park rangers, you have no choice but to accept that the land has spoken, albeit in the unfamiliar putonghua Chinese language, replete with charts and graphs of transects, zoning classifications, biomass dry weight measurement, Spatiotemporal Variations of Global Fractional Vegetation Cover Based on GIMMS NDVI Data. It is not only the jargon that is bewildering, but that the data contradicting the direct perceptions by Tibetans of the health of their grasslands comes from measurements made by satellite cameras hundreds of kms above the planet, which is what GIMMS NDVI means.

When the land commands its people to begone, the exclusionary termination is merely the systemic racism of the Han dressed as the voice of the rivers and lands. The starting point of China’s gaze into Tibet is that all that can be seen is lack, absence, remoteness, danger, unnatural cold and life threateningly thin air. This has been formulated for decades in the style of a Marxist dialectic: there is a contradiction between grass and animals, 草和动物有矛盾, cǎo hé dòngwù yǒu máodùn. To Han from agrarian regions, unfamiliar with the foundations of pastoralism, this seems self-evident: the more grazing animals you have, the less is the biomass of grass; conversely, if you remove the grazing herd, more grass will grow.

To Tibetans, deeply familiar with assessing and adjusting the grazing pressure of their animals, always moving on well before the health of the sedges and grasses is compromised, this official assertion of a problematic seems ridiculous. The 400 million pastoralists worldwide would agree.

Now China has come up with a slogan that cannot be laughed at as preposterous. Instead of positing grass and grazing as either/or, zero/sum polar opposites, it is now the land that is giving up on the people. This proposition is unanswerable, although scientific journals are full of fieldwork reports showing moderate grazing pressure in Tibet actually enhances biodiversity.[4]

“TIMELESS” TIBETANS ENTERING HISTORY

Once the graziers are gone, almost always to brand new villages hundreds of kilometres away, where herd animals are forbidden, there are no eyes to witness what happens to lands and rivers which have rid themselves of their people. Who will witness the rebranding of pastures, rivers, mountains and glaciers as tourism destinations, hydro dams, wind farms and photovoltaic arrays?

For China this is progress, productivity, making use of the factors of production, by abandoning the primitivity of relying on heaven. Dams, grids and “green” energy tech cannot co-exist with primitives wandering about, but it would be unskilful to say so directly. Instead, it is the land, and the rivers, that need to be spared human use, to recover by themselves, ready for the next colonising wave to enter.

The new slogan dovetails perfectly with the poverty alleviation campaign, which has officially put an end to all poverty in Tibet. Not only can the land no longer bear the people, the people remain forever poor because the land is so fragile, unproductive, and contiguous with the next plateau and the next, which are just as lacking in factors of production. So when the land rejects its people, this is actually a blessing, since China’s benevolent party-state will house the people far away, with nothing to do, often in a border district where the only requirement is to perform loyalty to the sovereign state.

Not only does the land tell Tibetans they must leave, instructional videos show them how to be grateful for their new houses, access to Chinese language education, and to consumer goods: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/HpdnUEzzd1OZWk3qLiEPvg

On offer is a complete package of departure, then immediate arrival in consumer modernity. Instant transition from stewardship of landscapes to loyal citizen of the distant sovereign nation-state, as dependent transfer payee, a life with no purpose beyond consumption.[5] New dams, wind and solar landscapes, and power grids all play their parts in accelerating these collective exits, pursued by the party-state and all its works.

For China’s leaders this all makes sense. The foundational assumption, so self-evident it is seldom named or examined, is that the evident material poverty of the Tibetans is due to the barrenness of the mountains, poverty of the land, hypoxia and frigidity of the air. Who would choose to live there, if they had a choice? China can benevolently give the inherently poor of the contiguous poverty-stricken lands the choice of modern comfort in prefabricated foamed concrete panel houses bolted together. In return, all that is required is manifest loyalty.

Inconvenient facts are ignored. Research shows that sheep and large scale solar arrays work well together: the sheep keep the grass short, and shelter from rain and sun under the panels.

[1] In horticulture, solarization is a technique for killing everything in the soil so you can then plant your monoculture crop: “Solarization involves watering a patch of soil, covering it with clear [or black] plastic, then allowing trapped heat from the sun to bake the soil to kill off weeds and pests. A better term for this method might be soil sterilization because you’re not only killing weeds and pests; rather, you’re killing all organic life in the soil, even the good stuff like earthworms, mycorrhizal fungi, and bacteria that attack pests and break down nutrients to make them available to plant roots.” The plastic, once used, cannot be recycled.

[2] Amar Deep Tiwari, Yadu Pokhrel, Daniel Kramer, Tanjila Akhter, Qiuhong Tang, Junguo Liu, Jiaguo Qi, Ho Huu Loc & Venkataraman Lakshmi, A synthesis of hydroclimatic, ecological, and socioeconomic data for transdisciplinary research in the Mekong, Scientific Data | (2023) 10:283 | https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-023-02193-0

[3] Asian Development Bank, The Greater Mekong Subregion 2030 and Beyond: Integration, Upgrading, Cities,

And Connectivity, March 2021

[4] W. N. Zhang, Effect of a grazing ban on restoring the degraded alpine meadows of Northern Tibet, China, Rangeland Journal, 2015, 37, 89–95.

Houzer, E. and Scoones, I. (2021) Are Livestock Always Bad for the Planet? Rethinking the Protein Transition and Climate Change Debate. PASTRES.

[5] Zygmunt Bauman, Wasted Lives: Modernity and its Outcasts, Polity, 2017