IS UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE PROTECTING THE GYALMO NGUL CHU/NU/SALWEEN FROM DAMMING?

#7 in a series of 8 blogs on China’s latest plans for Tibetan rivers

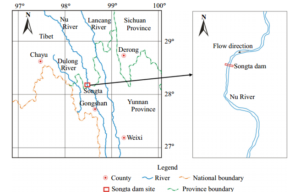

After the Gyalmo Ngulchu/Nu/Salween escapes the massive Songta dam and leaves Tibet Autonomous Region, it enters Gongshan county of Yunnan, formally assigned to the Dulong (or Drung) and Nu ethnicities. It also enters the UNESCO World Heritage Three Parallel Rivers protected area and high international visibility. In Tibet it remains a little-known river. Suddenly, in Yunnan, it becomes a major asset of global tourism. It continues to run in a gorge, and, as the UNESCO appellation suggests, is close to both the Mekong/Lancang and to the Yangtze, three rivers in parallel.

In China’s rigid system of assigning fixed territories to fixed ethnic nationality identities, the Dulong and the Nu are among the smallest. Their home is Gongshan county which, in the 2000 Census, had a total population of 34,750, of whom only 3,100 were Han Chinese. The Tibetan population was 1455. There are only 7000  Drung (or Dulong), whose lives are being rapidly changed by new hydropower dams.[1] The Nu are more numerous and less isolated from the tides of China’s history, with vivid memories of persecution during the Cultural Revolution.[2] But they are 27,000 people, confined to a modest area.

Drung (or Dulong), whose lives are being rapidly changed by new hydropower dams.[1] The Nu are more numerous and less isolated from the tides of China’s history, with vivid memories of persecution during the Cultural Revolution.[2] But they are 27,000 people, confined to a modest area.

The parallel rivers are assigned to different ethnicities. Immediately to the east, in the steep valleys of the Dza Chu/Mekong and the Dri Chu/Yangtze, is the Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Diqing/Dechen, with 120,000 Tibetans, and 230,000 of many other nationalities, according to the 2000 Census. This is now the mecca of authenticity eco-tourism, officially rebranded as “Shangri-La.”[3]

Despite their physical proximity, the Three Parallel Rivers are sundered by ascription to different nationalities, and by their paradoxical mapping as properties of the UNESCO World Heritage list.

UNESCO has not understood its own strengths, as franchisor of the World Heritage brand, to insist that protection means protection, and Three Parallel Rivers cannot be both a global tourist attraction and be the location for the 13 hydropower dams in China’s plans. Three Parallel Rivers is a fairly new World Heritage site. UNESCO should by 2003 have learned the lesson that its imprimatur is commercially valuable, nowhere more so than in a China that craves global approval, and is keen to monetise it. The irretrievable result of the mistake of 2003 is a huge World Heritage area, of 900,000 hectares, yet broken into 15 separate parcels of land, with the actual rivers that give the whole property its name entirely excluded.

What China officially proposed in 2003, and UNESCO accepted, was that the ridges and valley slopes separating these great rivers be inscribed, but the rivers themselves are excluded. The result is a patchwork park, ideally territorialised to fulfil China’s primary aim, of boosting tourism numbers. It fails on any other criterion for creating a coherent, protected landscape able to conserve biodiversity or indigenous cultures.

It is the rivers incising a rising plateau that made this landscape, yet they are not part of the UNESCO World Heritage Three Parallel Rivers, leaving China free to persist with damming them, and now to cross the protected and unprotected areas alike, with the marching power pylons of the west-to-east W2E UHV ultra high voltage cables sending hydro-electricity, in a straight line that utterly disregards topography, from Yunnan all the way to Guangzhou on China’s east coast. (see previous blogs in this series)

FRAGMENTING A COHERENT COMMUNITY-CONSERVED AREA INTO INCOHERENT, INCONSISTENT, MODERNIST PARCLES

UNESCO is caught in a mess of its own making, having failed from the outset to recognise its unique power to brand remote landscapes as an asset class of global attractiveness. UNESCO failed to leverage its brand, badly sought by China’s mass tourism planners, failing to insist that the price of conferring its brand and World Heritage designation, was the inclusion of a whole landscape.

Today, World Heritage can only complain, in vain, that this property of scattered jigsaw pieces: “raises questions of coherence and connectivity among and between the distinct components.” [4] Every few years UNESCO and IUCN send monitoring missions to the Three Parallel Rivers, which invariably report their increasing distress at: “Apparent decline in wildlife populations; Dams and related infrastructure; Lack of clarity of property boundaries; Mining; Inadequate management planning, including tourism planning.”

In due course, sometimes years later, UNESCO receives a reply from Chinese officials (the State Party in UN jargon), which offers vague assurances that illegal mining has been stopped (and where it has not been stopped, will most definitely be stopped) with flat refusal to encroach on the prerogative of the mighty State Grid Corporation to position its power pylons right across the Three Parallel Rivers protected area. The World Heritage missions of 2006 and 2013 asked for a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) of the UHV power line plan to string cabling in the opposite direction to the lie of the land, over the Three Parallel Rivers. In 2015, Chinese officials, afraid to challenge State Grid Corporation, gave as their only official response, that an SEA would be “too complex” and will not be done. Instead a Yunnan-based scientific research institute will do an SEA of the entire province, which will adhere to the official line that Yunnan stands to benefit greatly from exporting its hydropower to rich coastal provinces.[5]

Inevitably, World Heritage is reduced to glumly acknowledging how casually China brushes aside its complaint: “The notion of direct impacts of any of the 13 proposed dams in the vicinity of the property is rejected on the grounds of their location outside of the property and its buffer zones.”[6] To that UNESCO has no answer: it is powerless.

To China’s planners, the confluence of mass tourism, hydro dams, ultra-high voltage power lines and World Heritage listing are a win/win combination, each contributing to modernity, and the realisation of the “China Dream.” Clearly, World Heritage, led by scientific field reports, sees a clash, which is not resolved by artificially separating dammable riverbeds from their World Heritage valleys. To China, it is all development, which means the arrival in remote areas of wealth accumulation opportunities. What mass tourism, dam building and electricity export all share is the chance to get rich.

Anthropologists remind us that China teaches its citizens how, through tourism, to become consuming individuals with personalised tastes and desires: “In China, the Pocket Encyclopedia of Tourism made it clear that tourism was part of a consumption lifestyle that the country had to learn if it was to catch up with Western modernity: ‘In . . . Western countries, people have become used to hopping on airplanes on weekends or traveling in individual cars. This shows that . . . tourism is closely linked to the results of modern social development’. “Scenic spot” (jingqu or jingdian) is a generic category that encompasses nature reserves as well as small towns, segments of the Great Wall, and revolutionary sites and is central to the discussion of tourism development in China. Scenic spots tend to be gated and standardized, with visitors’ centres and shopping streets like Jiuzhaigou. Large-scale tourism is seen as a low-cost strategy for developing poor regions and ‘civilizing’ their inhabitants, many of them ethnic minorities. In particular, tourism development is a core component of the ‘Great Western Development’ strategy announced in 1999. More recently, the government has established ‘experimental zones for poverty alleviation through tourism’ (lu¨you fupin shiyanqu).”[7]

The reality is that, from the outset, Three Parallel Rivers was a project of the Yunnan provincial Construction Department, to whom construction, be it of mass tourism facilities, dams or ultra-high voltage power pylons are, indeed, construction. “The Yunnan Province Construction Department was responsible for the development of a ‘Master Plan for 2001–20’ for the Three Parallel Rivers National Park, which encompasses the World Heritage Area. The project has been coordinated since 1995 by the Three Parallel Rivers Scenic Zone Management Office, under the direction of the Chinese Ministry of Construction.”[8]

CAN THE DRUNG, NU AND TIBETAN PEOPLES SPEAK UP FOR THEIR LANDS AND RIVERS?

Initially, the indigenous poor within the World Heritage area were meant to be involved: “The plan is to preserve the ethnic cultures, focusing on certain villages, retaining their biological, cultural and landscape diversity while developing their economic potential in environmentally friendly ways.”[9]

UNESCO compounds its inability to protect what it nominally protects by failing to work closely with the minority nationalities, the Nu, Dulong/ Drung and Tibetans whose homes constitute the Three Parallel Rivers. Ethnic minorities took active part in the conservation campaign of 2003, the very time UNESCO inscribed this property as World Heritage, to halt China’s plans to dam the Nu River. Despite the widespread view in Beijing that these minority ethnicities are backward and uncivilised, they successfully mobilised, attracting mass support locally, and the forging of alliances with scientists and leading public intellectuals from Beijing with the ability to persuade China’s leaders to back away from hydro-damming. This successful social movement held the dammers off for a decade, but now, to the consternation of both UNESCO and the Nu, Drung and Tibetans, the dam builders and electricity grid builders are back, in force, with an authoritarian party-state backing them.

HYDRO EQUALS MODERNITY EQUALS POVERTY ALLEVIATION

In all remote areas, China invariably argues that big nation-building projects are for the benefit of the local indigenous poor. Park management now advances the familiar argument that hydro-damming Three Parallel Rivers is for the poor: “The region where the Three Parallel Rivers World Heritage Site spans is a poverty-stricken area, where several hundreds of thousands of people are still living under the poverty line. Science-based and rational resources use outside the scope of the property are important means not only for the poverty alleviation and socio-economic development of the indigenous people living in the region, but also for the ecological and environmental protection in the watersheds. In the process of economic development, Chinese government at all levels, as committed, will surely develop comprehensive plans, conduct scientific research and appraisal to implement heritage conservation and management pertaining to relevant laws and regulations, and harmonize the coexistence and relationship between development and the nature.”[10]

UNESCO is helpless to respond, having itself done nothing to maintain connections with the poor, or to provide them a channel to articulate their concerns, speak for themselves and assert a speaking position.

As a result, despite tourism industry rhetoric about minority nationalities living in harmony with nature, many inhabitants have been removed. “The World Heritage Committee fails to mention another topic that should have been of concern: the relocation of villagers from the ‘property’. As of 2003, the provincial authorities had reportedly completed the relocation of approximately 36,000 people (9,000 households) from the ‘protection area’, mainly to resettle in Dali and Simao prefectures. A further 19,500 people were scheduled for resettlement over the next few years, 60 percent of them from core zones of the area and the remainder from buffer zones. No information was available on how these people would be compensated or whether they would be offered support for livelihood restoration.”[11]

A more up to date account of how many people have been displaced by dams on the Mekong in Yunnan is also available: Dam-Induced Displacement and Agricultural Livelihoods in China’s Mekong Basin, Brendan A. Galipeau & Mark Ingman & Bryan Tilt, Human Ecology, (2013) 41:437–446

DRAWING BOUNDARIES

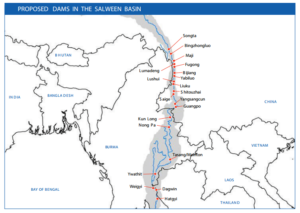

Planning the hydro dams has taken decades, and the definitive plan for the 13 dams in the parallel rivers was also finalised in 2003, the same year UNESCO branded the area. UNESCO is again helpless when China says the dams are none of UNESCO’s business. Park management now says: “The Report on Hydropower Development Planning on the Segments of the Middle Reaches of Jinsha [Yangtze] River was approved at the national level in January 2003. A hydropower development plan of ‘one headwater reservoir with eight cascade power plants’, respectively at Longpan, Liangjiaren, Liyuan, Ahai, Jin’anqiao, Longkaikou, Ludila and Guanyingyan was proposed. None of the above planned hydropower plants are located within the scope of the property.” [12]Everything is going according to plan, everything is legal and legitimate, World Heritage and hydropower can learn to live with each other. Knowing not only where the dams would interrupt each of the great rivers, but also how high the dam walls would be, China took care to draw the UNESCO property boundaries to fully exclude not only riverbeds but the full height of the dams when filled with impounded water.

The same decisive year, 2003, also saw finalisation of long terms plans for the hydro damming of the Dza Chu/Lancang/Mekong in the parallel river area; and again, park management denies that UNESCO has any authority: “Formulation of the Report on Hydropower Development Planning on the Section from Gushui to Miaowei of the Lancang River was completed toward the end of 2003. The report proposed a hydropower development plan of ‘one headwater reservoir with seven cascade hydropower projects’, respectively, at Gushui, Wunonglong, Lidi, Tuoba, Huangdeng, Dahuaqiao and Miaowei on the upper reaches of Lancang[Mekong] River. Of these hydropower plants, Gushui, Wunonglong, Lidi, Tuoba, Huangdeng and Dahuaqiao are in the vicinity of the property. None of the above proposed hydropower plants are located within the scope of the property and its buffer areas.”

In addition to these dams, four more are planned for the section of the Nu/Gyalmo Ngulchu/Salween that flows through the Three Parallel Rivers: known as the Maji , Yabiluo, Liuku and Saige dams.

A BIG NEW RESERVOIR ATOP EACH DAM CASCADE ON ALL THREE PARALLEL RIVERS

On all three rivers, the plan is for a “headwater reservoir” above the main hydro dams, to accumulate water and store it, to provide more flow and thus more predictable hydropower generation, beyond the summer monsoon season. This inevitably means interfering with natural environmental flows and disrupting the life cycles of many species, especially fish which migrate upriver to breed. UNESCO is painfully aware of what is now at stake: “The site contains more than 200 species of rhododendrons, over 100 species each for gentians and primulas, and many species of lily and orchid, as well as many of the most noted Chinese endemic ornamental plants: gingko, the dove tree, four species of the blue poppy and two species of Cycas. The diversity of conifers is outstanding; in addition to dozens of the main mountain forest trees (Abies, Picea, Pinus, Cupressus and Larix), there are many endemic or rare conifers. There are also around 20 rare and endangered plants which are relict species and survived the Pleistocene glaciations, including the Yunnan yew. The area is the most outstanding region for animal diversity in China, and likely in the Northern Hemisphere. Two-thirds of the fauna within the nominated site are either endemic, or are of Himalayan-Hengduan Mountain types. The area is believed to support over 25% of China’s animal species, many being relict and endangered. Many of China’s rare and endangered animals are within the nominated area: 80 are listed in the Red Book of Chinese animals, 20 of which are considered endangered.”[13]

The enormous weight of headwater reservoirs can be sufficient to trigger earthquakes and landslides, both because impounded water is heavy and because water seeps down to fault lines and lubricates their straining to suddenly move.[14]

On the Gyalmo Ngulchu/Nu/Salween, China’s hydro engineers are tempted to supplement flow by transferring water from a different catchment basin, that of the Yarlung Tsangpo/Brahmaputra. Although the Yarlung Tsangpo, the major river of southern Tibet, takes a long course from its source in far western upper Tibet, draining as it goes the entire northern flank of the Himalayas before dramatically cutting right through the Himalayas to India and Bangladesh, the Yarlung Tsangpo also has tributaries well to the east, in fact the Parlung Tsangpo, at its subglacial source of Ra’o Tso lake is very close to a side stream that flows into the Gyalmo Ngulchu/Nu.

The uppermost Parlung Tsangpo at one point (~29°25’N, 96°45’E) is as little as 35 kms away from a tributary of the Nu, also in its upper reaches. Even though –inevitably- what separates these two watersheds is a mountain range that would have to be tunnelled, this closeness is a tempting target for engineers, and on the official wish lists of China’s planners.

Apart from the necessity of tunnelling, in a landscape so rugged and remote that few Tibetans have seen it, preferring to believe it is a hidden land of bliss, there are other problems. The People’s Daily E-government website acknowledges that at this closest point the Parlung Tsangpo is below the Nu River tributary in altitude, which would necessitate pumping. To make things harder still, the two rivers flow in opposite directions: the Parlung Tsangpo heads towards the northwest, the Nu to the SSE, so other sites to connect them have even great disparities in elevation. But, the People’s Daily E-government site announces cheerfully, the answer to gravity is pumping, and there are plenty of sites on the Nu River suited to hydropower stations to generate the electricity needed.[15]

Thus it is possible that the four hydro dams planned for the Nu River just after it leaves Tibet would be needed primarily for pumping water uphill, across watersheds and through mountains. That could result in an enhanced flow, spread across more months of the year, to keep more turbines lower on the Nu spinning, and sending their electricity to far Guangzhou.

It is the hydropower potential of the Nu (Gyalmo Ngulchu in Tibetan, Salween in Myanmar) that is the attraction. This is not the only place where China is faced with the same problem of having to overcome the law of gravity. On the Dadu River, far above its confluence with the Yangtze, the reason for expensively pumping water uphill into the Yellow River/Ma Chu is the water itself, much needed by the depleted Yellow River. Here too, on the Nu, the argument is somewhat circular: we can get more water into the Nu by pumping it from the Parlung Tsangpo, by using hydro-electricity, so that the increased flow will power more hydro-electricity in a cascade of dams wherever damming is possible. It is little wonder this scheme, while still on the books, is on the back burner.

HOW TO FAIL TO CONSERVE WORLD HERITAGE

Of the 48 World Heritage sites officially listed as “in danger”, not one is in China.[16] UNESCO can argue that, as a UN agency, it is bound to work with the State Party, as its sole partner, and has no role working also with civil society, even though the consensus among biodiversity conservationists worldwide is that partnerships with local communities, who have conserved landscapes and biodiversity for centuries, is the most effective way of maintaining conservation.

But UNESCO works closely with IUCN, an organisation of biodiversity scientists which strongly promotes indigenous conservation, and, as an NGO, is able to do community work to strengthen alliances and co-management strategies that empower the disempowered to take a leading role. IUCN formally recognises, as a category, what it calls Indigenous and Community Conserved Areas (ICCAs) as having a much longer and more successful history than officially protected areas such as World Heritage. But on the ground, those connections have not been made. As a result, China is free to speak for the local communities, with no fear of contradiction, and to proclaim hydro damming as a poverty alleviation program for the benefit of these whose voices are utterly absent from the debate.

China’s official managers of the Three Parallel Rivers World Heritage explicitly argue for hydro damming: “Necessities for developing hydropower projects: China remains to be a developing country and that the trend of economic growth and protection of the natural environment is an inexorable trend. The growing demand for power energy will accompany such economic growth. Enhancing the natural environmental protection necessitates developing production means for clean and renewable energy. All countries worldwide, with no exception, give priority to developing hydropower energy. Hydropower generation is still regarded as the cleanest, renewable and can be achieved in large scale. China is relatively rich in hydropower resources that are clean and renewable and are high quality resources for power generation.

“In one way, the China’s inscription of the Three Parallel Rivers as the world natural heritage was intended as means to enhancing its efforts on the protection of the natural resources and the environment; on the other, only when science-based extraction and utilization of the ‘hydropower of the three rivers’ is implemented to promote the sustainable socio-economic development of the Three Parallel Rivers Region, can the ideal win-win goals of natural resources protection and sustainable development can be attained. The Three Parallel Rivers Region of Yunnan Province is a poverty-stricken area, several hundreds and thousands of people are still living below the poverty line. Science-based extraction and utilization of the hydropower resources of the three great rivers is an inevitable choice not only for sustaining China’s economic growth, protection the natural resources and environment, but also for the socio-economic development, poverty reduction in these regions of Yunnan and environmental protection in the watersheds in Yunnan Province.

“In actual implementation of the hydropower projects, as the State Party, China will responsibly and adequately harmonize the relationship between the sustainable uses of the hydraulic resources and the co-existence of man and the nature.”[17]

This is an uncompromising legislative voice, speaking on behalf of both nature and the human population of the three rivers, with no fear of contradiction. The peoples of the Three Parallel Rivers are systemically disempowered, because from the outset UNESCO gave China the power to define on what grounds the area should be protected. UNESCO World Heritage is a broad, inclusive idea, encompassing culture and nature. UNESCO has 10 criteria enabling a nomination to proceed, the last four make no mention of the human presence in a landscape, and it is under those four criteria that China applied for the Three Parallel Rivers inscription, solely as a landscape containing superlative natural phenomena, exceptional natural beauty and aesthetic importance; as outstanding examples representing major stages of earth’s history; and as outstanding examples representing significant on-going ecological and biological processes in the evolution and development of terrestrial, fresh water ecosystems and communities of plants and animals; plus containing the most important and significant natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological diversity, including those containing threatened species of outstanding universal value from the point of view of science or conservation.

UNESCO’s formal distinction between cultural criteria and natural criteria has allowed China to formally exclude the human population from any mention in the actual criteria for inscription, even though UNESCO does talk of “cultural landscapes.” Having excluded the people from any value in why the Three Parallel Rivers constitute World Heritage, China is now free to bring in the human population, as objects of the developmentalist party-state, to justify hydro damming and ultra-high voltage electricity export. To this UNESCO has nothing it can say.

UNESCO finds itself struggling to protect the landscapes, human lives and biodiversity that World Heritage inscription is meant to protect. In reality what World Heritage offers is a form of capital that is appropriated by a developmentalist party-state as world stamp of approval for a mass tourism destination. The anthropologists note that this does go back to the inscription process of 2003: “The social engineering function of tourism [in China]—its mission to ‘shed the light of modern civilization on every rural corner’ -remains strong, tied as it is to the state’s drive to improve the “quality” (suzhi) of the population by creating modern consumer-citizens. If the promotion of consumption is explicitly linked to the valorization of ‘openness’ and globality, then it is hardly surprising that World Heritage has been central to the promotion strategy pursued by China’s tourism authorities. Christine Tam, Director of Conservation Area Planning for the Nature Conservancy’s China Programme, which helped prepare the nomination of the Three Parallel Rivers in Yunnan Province in 2003, disappointedly comments that World Heritage ‘feels like a tourism designation, not a designation to protect resources’”.[18]

When Tibetans and other minority nationalities joined with Beijing scientists and public intellectuals, in 2003, to successfully oppose the hydro damming of the Gyalmo Ngulchu/Nu local Tibetan communities defending their homelands were indeed poor, yet they spoke out. In 2016, the Tibetans are better off, better educated, with a wider range of income sources, and thus better able to speak for themselves.

Many Tibetans have become entrepreneurs of the tourism boom, appealing both to mass domestic Han Chinese tourists and international visitors seeking the authentic Shangri-La. The high pastures above the rivers are rich in Yartsa gumbu (ophiocordyceps sinensis) a caterpillar fungus prized in China as a powerful restorative medicine, and Tibetans have made fortunes. China has also encouraged the growing of red wine grapes in the cool climate of these Tibetan uplands, again providing income, training and education for Tibetans, who can see how to maintain both modernity and tradition, if allowed.[19] If UNESCO chose to work with this new generation of educated and articulate Tibetans, much could be achieved, that would actively conserve World Heritage values.

This blog is a long form version of a paper to be presented to the World Heritage Watch conference, 8 July 2016: http://www.world-heritage-watch.org/index.php/en/

[1] Edward Wong, Chinese Modernization Comes to an Isolated People, NY Times, April 24, 2016

[2] Mireille Mazard, Powerful Speech: Remembering the Long Cultural Revolution in Yunnan, Inner Asia 13 (2011): 161–82

[3] Ashild Kolas, Tourism and Tibetan Culture in Transition, Routledge, 2008

[4] Item 7B of the Provisional Agenda: State of conservation of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List, World Heritage 39 COM, WHC-15/39.COM/7B, Bonn, Germany 28 June – 8 July 2015

[5] http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1083/documents.

[6] Three Parallel Rivers of Yunnan Protected Areas State of Conservation SOC report by UNESCO World Heritage 2015 http://whc.unesco.org/en/soc/3236

[7] Joana Breidenbach and Pa´l Nyı´ri, “Our Common Heritage”: New Tourist Nations, Post-“Socialist” Pedagogy, and the Globalization of Nature, Current Anthropology Volume 48, Number 2, April 2007

[8] Ashild Kolas, Tourism and Tibetan Culture in Transition: A place called Shangrila, Routledge, 2008, 23

[9] www.unep-wcmc.org/sites/wh/Three_Parallel.html

[10] Management Committee of the Three Parallel Rivers Yunnan Protected Areas, World Natural Heritage Site Report on the Status of Conservation for the Three Parallel Rivers Protected Areas of Yunnan, China, Jan., 2015 http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1083/documents

[11] Ashild Kolas, Tourism and Tibetan Culture in Transition: A place called Shangrila, Routledge, 2008, 24

[12] http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1083/documents

[13] World Heritage Nomination – IUCN Technical Evaluation, Three Parallel Rivers Of Yunnan Protected Areas, (China) Id Nº 1083

[14] http://www.src.com.au/earthquakes/seismology-101/dams-earthquakes/

https://www.internationalrivers.org/earthquakes-triggered-by-dams

[15] http://ezheng.people.com.cn/proposalPostDetail.do?boardId=1&view=1&id=2118097

[16] http://whc.unesco.org/en/danger/

[17] The Management Committee of the Three Parallel Rivers Yunnan Protected Areas World Natural Heritage Site; Report on the Status of Conservation for the Three Parallel Rivers Protected Areas of Yunnan, China, 6-7 http://whc.unesco.org/document/135083

[18] Joana Breidenbach and Pa´l Nyı´ri, “Our Common Heritage”

[19] Brendan A. Galipeau, Socio-Ecological Vulnerability in a Tibetan Village on the Mekong River, China; Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies, 34 #2, 2014

also: http://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/xmlui/handle/1957/31328#?