ELECTRIFYING THE WORLD FACTORY FROM TIBET

#6 in a series of 8 blogposts on China’s latest plans for Tibetan rivers

While big reservoirs to capture and divert waters of Tibet to northern China are new, official plans to dam Tibetan rivers for hydropower have been known for many years.

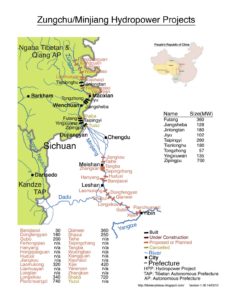

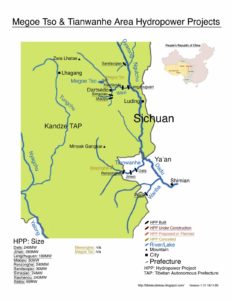

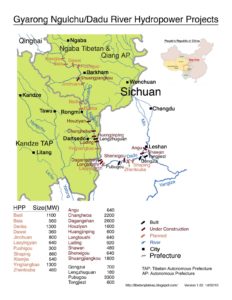

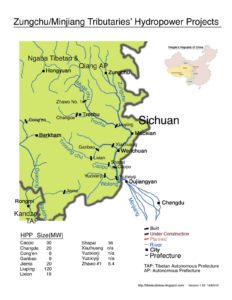

Maps of the planned cascades of dams, on almost all the rivers traversing and descending from Tibet, have been published by exiled Tibetans worried at the impact of planned dams on Tibetan communities used to self-sufficiency in the deep valleys of precipitous Kham. The dams have been featured on China’s official websites for many years, and listed in successive Five-Year Plans, but slow to build. Generally the dams that have been built, some of them very big, have been somewhat downriver, just beyond Tibetan areas. The plan all along has been to steadily move the dam building upriver, to move gradually into steeper terrain, higher altitudes and districts more remote from lowland China.

But the announcement that changes everything came in April 2016, of a start on the Suwalong hydro dam, straddling the border China has drawn that bisects Kham, with the Yangtze (known in Chinese, on this stretch, as the Jinsha) as the actual boundary. Between the Tibetan towns of Bathang, on the Sichuan side of the Dri Chu/Yangtze/Jinsha, and the town of Markham, on the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) side, this dam is specifically designated as the first to be built for the purpose of exporting electricity right across China to east coast cities and industries.

T he Suwalong dam is the start of a new era for Tibet, of resource extraction on a scale not seen before, for very distant beneficiary users in the world factory of Guangzhou and Shanghai.

he Suwalong dam is the start of a new era for Tibet, of resource extraction on a scale not seen before, for very distant beneficiary users in the world factory of Guangzhou and Shanghai.

The official announcement states: “The Suwalong hydropower station is the first large-scale hydropower station constructed on the upper reaches of the Jinsha River. This is an important project regarding supporting Tibetan socio-economic development which was defined at the 5th National Conference on Tibet Work; it is also the first project regarding West-East electricity transmission projects carried out by the central government. The construction of the Suwalong hydropower station is also very significant for the construction of the West-East electricity transmission project, therein pushing forward ‘transferring Tibet’s electricity out’ as well as the socio-economic development in the local area.”[1]

By any measure, this is a large dam. The total installed capacity of the hydropower station is 1,200,000 kilowatt (1.2GW) with a total capital expenditure budget of 17.89 billion yuan (USD 2.89 billon). Officially, “at the moment, the construction objects such as roads, power supplies and camps within the Suwalong Hydropower Station construction site have basically been finished, and the over 900-meter-long diversion tunnel are under rapid construction. The body part of the project will start to be constructed in November, 2017 after the dam on the Yangtze River is done.” [2]Within this tight and narrow valley, the entire river has to be diverted during the main dam construction, and work is well under way. The dam wall is 112 m high, and output is expected to be 5,400 gigawatt hours (GWh) of electricity a year when completed in 2021.

There is much scientific evidence, specifically at Suwalong, of at least three major earthquakes which triggered landslides big enough to block the Yangtze, later bursting disastrously as the blocked river backed up.[3]

Going upriver from the Suwalong dam, no less than 17 more dams athwart the main channel of the Dri Chu/Yangtze are planned, deep into the Tibetan Plateau. These are known in Chinese as the Batang, Lawa, Yebatan, Boluo, Yanbi, Gangtuo, Guotong, Sewu, Xirong, Cefang, Genzhe, Leyi, Dequkou, Ruoqin, Lumari, Yage and Marigei dams.[4]

Going downriver, below Suwalong dam, on the Yangtze, there are a further 18 dams, all upriver from the Three Gorges, of which four: the Jinanqiao, Ahai, Xiangjiaba and Xiluodu dams are operational. By 2010 the power line, all the way from Xiangjiaba to Shanghai, just under 2000 kms, was in place, proudly built by the Swiss/Swedish company ABB.[5] Siemens was a major supplier of high technology.[6] The dam, at the foot of the Tibetan Plateau, became fully operational four years later, in late 2014.[7] Likewise, the neaby Xiluodu dam, second only to Three Gorges in size, became fully operational in 2014 after a build that took a decade.[8] This list is only of dams on the main channel of the Yangtze, and does not include dams on tributaries, such as the Yalong River of Tibet, on which the world’s tallest dam has been built, Jinping 1 (and below it Jinping 2) in a seismically active zone, with evidence already that the weight of impounded water is triggering more earthquakes, even though these dams are still new.[9]

These dams, plus the Three Gorges, already have a major impact on the flow of the Yangtze. Researchers report that: “A significant decrease in discharge from the upper basin occurs in October as water is stored for later release in January to March.”[10] This seasonal imbalance will only intensify as more water is impounded in more dams for hydro power purposes.

To China’s planners, and the bosses of the huge state-owned corporations dominating energy supply, the case for extracting hydropower from Tibet is cogent, self-evident and the basic argument has remained constant over many years. For example, the powerful chairman of the State Grid Corporation board, Liu Zhenya reminds us that extracting energy from Tibet is not new. Millions of tons of oil have been extracted from the Tsaidam Basin of northern Tibet since the 1980s, and gas since the start of this century.

In 2013 Liu pitched his case for the high modernist fantasy of a completely integrated grid of extraction, inclusive of all forms of energy, from north to the south, and from west to east. “Driven by China’s growing economy, the demands for energy in developed regions will increase dramatically and the imbalanced distribution of energy supply and consumption areas is bound to become more notable. That makes large-scale, cross-regional or long-distance allocation of energy resources inevitable. In the future, China will generally transport energy from the west to the east, and from the north to the south, and the scale of energy flow will expand considerably. The scale of power transmission from the west to the east and from the [coalfields] north to the south, is expected to be substantially expanded. Oil will continue to be transported from the west to the east. Natural gas will be transported from the west to the east. The scale of energy transport will become bigger and bigger, which will impose higher demands on energy transport. Building a highly modernised energy transport system has become a major strategic task.”[11]

This is the language of high modernism, of logic, efficiency, necessity and inevitability; to be accomplished through the mechanism of allocation by the eye of a party-state with the capacity to know precisely what is objectively needed. Yet Liu’s language also recapitulates the metaphors of traditional Chinese medicine, with its energy flows throughout the imagined body, and the importance of maintaining balanced flows to all organs, reducing excesses and replenishing deficiencies. This is a central planner’s high modernism with Chinese characteristics. China is a singular geobody, in which all limbs and organs must be in balance.

Liu graduated from the Shandong Industrial Institute, and joined the Communist Party in 1984. He served as director of the Shandong Provincial Electric Power Bureau until 1997. He was president of the State Grid Corporation of China from 2004 to 2013. He was also an alternate member of the 17th CPC Central Committee. In 2013 he became Chairman of the Board of Directors of the State Grid Corporation of China.[12] One year later China’s government auditing agency alleged more than $1 billion was misappropriated in less than four months last year while constructing and running portions of a major electricity grid system. “China National Audit Office said its probe into certain contracts for a west-to-east electricity-transmission system uncovered theft and contract irregularities totaling 6.7 billion yuan ($1.1 billion); in some areas, the problems amounted to 16% of the value of the contracts reviewed.” [13] Liu Zhenya survived the corruption investigation and remains in charge.

To Liu and his fellow central leaders, it is self-evident that Tibetan water and hydropower must now nourish eastern China, since the developed east has done so much, in the “aid-Tibet” program, to nourish Tibet, often depicted as a body that is weak, stagnant and sickly, in great need of a blood transfusion.

Mr. Liu drew an analogy: “The Internet is like the nervous system, while electric grids are like the blood vessels. As the nervous system is interconnected, so must the blood system be.”[14] Tibet, previously depicted as anaemic, to be revived by a blood transfusion from the Han older brother, will now become a blood supplier to China. By literal extension of UHV DC to the world, China will in turn become blood supplier to the world, for profit.

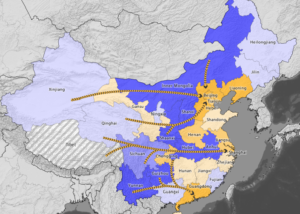

Once the cascade of dams is built, not only in the current 13th Five-Year Plan period, but over the two successive Five-Year Plan periods, as envisaged, the amount of electricity to be exported from Tibet is huge. Liu Zhenya wrote in 2012: “Hydropower will be developed in Tibet and transmitted to other regions on a large scale. Power generated in the large hydropower bases will be transmitted from Sichuan to central and eastern China, and from Yunnan to Guangdong. The volume of hydropower from the southwest region will reach 54.5 GW (gigawatts), 76 GW and 120 GW by 2015, 2020 and 2030 respectively.”[15] By comparison, the world’s most powerful hydro dam, the Three Gorges, has a generating capacity of 22.5 GW. Thus, by 2020, the target in Tibet and just below, is for the equivalent of three Three Gorges Dams by 2020, and almost five by 2030.

Liu is certain these west-to-east (W2E) projects are needed, as electricity demand will continue to grow. He has little to say about mitigating climate change, but has glowing projections of future demand: “In the coming 20 years, the electricity demands in China will continue to grow rapidly and the eastern and central regions will be the load centres in China. Studies show that China’s peak loads in 2015, 2020 and 2030 will respectively reach 1010GW, 1410GW and 1940GW, or respectively 1.5 times, 2.1 times and 3.0 times the level in 2010. Total power consumption nationwide will respectively top 6300, 8600 and 11,800 TWh (terra watt hours).”[16] Even if all 181 dams in eastern Tibet are built as planned, they will still provide only four per cent of China’s electricity consumption, and that much only if they operate continuously rather than as peak load supply hours only.

Whether the new dams will actually transmit as much electricity as planned is uncertain. Proponents of dams put the best case scenario, but in reality, hydro dams often fail to meet expectations. “China’s installed capacity in hydro is impressive, but its contribution to the country’s overall energy mix is far more modest. Due to rushed construction and other industry problems, Chinese dams are highly inefficient, with an average capacity factor of 31% – about two-thirds the world average. Capacity factor refers to the amount of electricity produced compared to the installed capacity.”[17]

Transmitting electricity from Tibetan rivers west to east (W2E) has become an iconic project of the developmentalist party-state, a project of symbolic importance similar to the Three Gorges dam was for an earlier generation of central leaders. W2E (xi dian dong song),must succeed, and the discovery of corruption must not slow it. China rewards energetic and highly visible bureaucratic entrepreneurs like Liu Zhenya, who get things done, whatever it takes.

Extracting electricity for the rivers of Tibet is only the start for Liu Zhenya and State Grid Corporation, who now promote a global vision of installing the UHV DC technologies to be installed in Tibet, on a planetary scale. Liu is now free to scale up his vision of unifying China with UHVDC power lines that make it a unitary geobody, into an even grander global vision of electrical interconnectedness, which his State Grid Corporation would build. Having made China one geobody, Liu now talks of a global grid, interconnected by UHV DC cables, in his China State Grid vision for a $50 trillion global power network that harnesses Arctic winds and equatorial sunlight.[18]

Leveraging the Tibet model into a pitch for a worldwide expansion of SGC technologies, Liu Zhenya enthusiastically promotes his concept of “Global Energy Interconnection” (GEI) at conferences sponsored by State Grid Corporation,[19] in speeches and his new books, published in 2014 and 2015, Ultra-High Voltage AC/DC Grids and Global Energy Interconnection. Liu enthuses that it is technically possible, using UHV DC power lines, to transmit electricity from Xinjiang, north of Tibet, all the way to Germany, and to do it cheaper than Germany can generate energy from wind and sun. “He said excess wind power from the northwestern Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region can theoretically be exported to power-short Germany via some 6,000 kilometres of long-distance, high-capacity UHV power lines, on which State Grid has said it has achieved technological breakthrough and commercial success. It has built seven such lines and plans to complete nine more in mainland China by the end of next year. According to its research institutes’ estimates, it costs 8 US cents per kilowatt-hour to generate and send wind power to the Xinjiang grid, and 4 US cents to then send it to Germany via UHV lines. The total cost of 12 US cents is half that of clean power generation cost in Germany, Liu said.”[20]

This global vision would extract electricity from Africa to be sent to Europe via UHV DC power lines, and would also tap the gales sweeping the Arctic. “According to the State Grid’s timeline, by 2030, all countries’ grids will be connected within each continent. By 2050, all continents’ grids will be connected with each other, and 80% of the world’s electricity consumption should be covered by renewable sources. By then wind turbines at the North Pole and solar panels along the equator should play central roles in worldwide energy production.”[21]

ULTRA HIGH VOLTAGE NATION BUILDING

The transfer of electricity from west to east W2E is a metaphor of reciprocity, of national unity, of exchange constitutive of a unitary nation-state. The language used deploys a striking metaphor of the horizontal line, inscribed three times across the geo-body of China, once in the north, once in the centre and once in the south, creating a singular China encompassing all difference. The three broad, bold brush strokes across China, from left to right, west to east, establish China as a natural entity, pre-ordained to succeed by the long-established north to south hauling of coal, the criss-crossing of high speed rail lines and now “transferring Tibet’s electricity out” to the east. This is nation-building on a grand scale, and the dividend for decades of modernising and civilising Tibet by building infrastructure. .

The same discourse strategy is used to define the high speed rail network, but less totally, as there are no plans to extend high speed rail beyond the fringes of the Tibetan Plateau, which is one quarter of China’s landmass. The west to east W2E electricity transfer is bolder, ascending the edges of the plateau, successively extending the reach of the state further up the valleys incised over millions of years by Tibetan mountain rivers cutting as fast as the Tibetan Plateau has been rising.

Much as the United States fulfilled its manifest destiny by pushing westwards until it became one nation from sea to shining sea, Chinese researchers draw explicit parallels between developing western China and the history of the American West.[22]

China’s version of manifest destiny, the “China Dream”, is of a unitary state that has assimilated ethnic difference, transcended identity based on minority nationality, merging all into a single Chinese nationality; in which the exploitation of the “great west”, or xibu da kaifa, is seen as the naturalised reciprocity of the mandatory gift relationship, the return on capital invested in civilising the remote west. Most Chinese analysts, by lumping all western provinces together, find that the capital expenditure on infrastructure in the west has generated economic growth, as it was supposed to. But some researchers, looking at water diversions and transferring Tibet’s energy out, invoke the worldwide concept of the resource curse. For example: “East China is advantaged for relatively plentiful capital and institutional resources, while West China is disadvantaged for the “Resource Curse”. It is obvious that East China would not have developed as rapidly without the “food and blood” for industry from West China, and the sustainable development of East China has to be based on the ecological restoration and economic development of West China. Widening the economic gap between East and West China will destroy the harmonious coexistence of a multi-ethnic society and affect the nation’s political stability.”[23]

Since the turn of the century, official discourse has emphasized the need to redress inequality, be it the growing gap between neglected rural areas and booming cities, or the widening gap between east and west, or between Han and minorities. Three decades of letting those with the best factor endowments get rich first left rural and western China feeling much neglected, falling behind, and without much government provision of health care or social safety nets in case of destitution. In the 21st century’s opening years the rhetoric changed, promising to be more inclusive of those left behind. That was the context for xibu da kaifa 西部大开发, usually rendered into English as Western Development Strategy, but more literally “opening up the great west.” Opening up, like coming out and transferring out, are at first glanced benign, with connotations of a process that is both natural and inevitable. However, all these telling formulations originate in the point of view of the Han, to whom the resources of the west are opened, for exploitation. They are the stance of the outsider approaching the west, seeking its wealth, naturalising the flow of public goods of the west into China’s coal washeries and electricity intensive smelters.

Officially, this is development, an unquestionable and self-evident good, which benefits the recipient, bringing the Tibetans into modernity and the market economy. Diversion of rivers and cascades of hydro dams may be the price Tibet pays for integration into China, but they are also deemed beneficial to Tibet, constituting Tibet’s revitalisation, an end to stagnation, remoteness and weakness. It is even said that Tibet was timeless and outside of history, but thanks to China’s gift of development, Tibet has now entered history, according to a Marxist concept of the necessary path of social evolution.[24] Having entered history, Tibet may now progress, and eventually attain modernity and civilisation. That has been the standard Chinese narrative for many decades.

State Grid Corporation (SGC), the driver of W2E UHVDC extraction of electricity from Tibet, is enormously powerful, both due to its great size and capacity to spin mythologies of “unifying China” by its power lines. Of China’s many state-owned enterprises SGC is a national champion, which has accumulated such wealth that it shrugs off corruption investigations, and forges ahead with its vision of acquiring assets globally, to knit into a planetary electricity grid, owned and controlled by SGC.

Within China SGC remains opaque, with no private shareholders and no obligation to report to stock exchanges on how it runs its business. In an attempt to break up this monopoly, in 2002 China’s central leaders split the National Power Corporation in two, with the newly created SGC awarded a territorial monopoly over most of China, while Southern Power got the rest. The plan was to further break these monopolies into five grid corporations, a pressure that SGC managed to successfully resist.[25] Nothing has been heard for a long time of reducing SGC’s domain.

State Grid Corporation is highly profitable, yet answerable to no-one other than the Communist Party. Fortune 500 ranks State Grid as the world’s seventh biggest corporation, ahead of Apple, Volkwagen and Toyota.[26] Its accumulation of wealth enables it to bid to take ownership of state grids now being privatised in other countries: currently State Grid is bidding to become the owner and operator of the grid of Australia’s richest state, New South Wales. This capacity to “go out” and buy profitable assets worldwide endears State Grid to party leaders, who want national champions, able to make China into more than factory to the world, becoming a brand in its own right. Under Liu Zhenya’s leadership, SGC is now able to enlarge the “China Dream” to embrace a whole world of electricity grids, interconnected by SGC, on a planetary scale and with Chinese characteristics.

This unchecked monopoly power makes some in China uneasy. In 2014 Caixin reported: “Some reformers have also called for further splitting up grid companies to break up their monopolies. The 2002 document set a plan for the State Grid to establish five regional grid companies with independent operations, but over the following years that idea was dropped. Some in the industry say the only way to push forward reform of the industry and improve market efficiency is to break up the grids. Bi Keli, deputy general manager of the Shandong branch of China Guodian Corp, one of the five major power generators, said in a recent article that the grids are the main obstacle to reform. Shao also said in a recent public speech that the gigantic central government-backed enterprises have become cradles for corruption due to their dominance over resources. He said the only way to improve operational efficiency and enhance government supervision is to split up the grids.”[27]

Despite promises to give private enterprise the dominant role in the economy, and famous brands such as Alibaba keen to become an electricity retailer, there is no sign State Grid Corporation will have to share its profit base.

It is equally hard to imagine State Grid scaling back its ambition to dam the rivers of Tibet and bring back to Guangzhou and Shanghai a dividend of Tibetan power. State grid has woven the damming of Tibet into a master narrative of unifying China, of the three horizontal lines of power pylons W2E, bringing electricity generated in Tibet almost instantaneously to consumers in far distant cities.

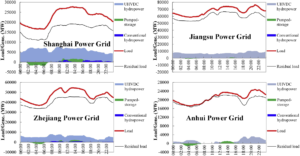

This will mean that the rhythms of those mountain rivers will in future have to closely match the rhythms of electricity demand a thousand or more kms away. Unlike other commodities, electricity cannot be stored; it must be generated at the time it is needed.

Complex calculations published in 2016 suggest once the dams are built and the turbines are turning, the amount of water released will fluctuate not by season, or month, or day, but by the hour, depending on demand, and how cross-country direct current can be integrated into the national grid of alternating current. According to the experts of the Institute of Hydropower and Hydroinformatics, Dalian University of Technology, the Tibetan dam outflows must be adjusted every 15 minutes.[28] The people of Tibet, long disempowered by “development”, will find their rivers similarly disempowered, their flow rate governed by urban demand thousands of kms away.

In the great interconnected scheme of State Grid Corporation, this is all positive. Electrifying Tibet and transmitting the power across China will be of great benefit to Tibet, SGC’s Liu Zhenya says. What he proposes is a win for all. The environment will benefit from greater use of renewable energy, resulting in less air pollution and acid rain. Long distance UHV DC transmission, Liu argues, will free up a lot of valuable eastern province real estate currently used for coal transport, storage and coal-fired electricity production. Meanwhile, western China, including Tibet, has land to spare. Liu writes: “Accelerating the development of power transmission can help optimise and utilise land resources in the country. China’s western region is sparsely populated, with abundant land resources, while the eastern and central regions, which can be used for the restructuring and development of other industries, with high value-adding potential.”[29]

The Tibetan Plateau became a well-known brand within China when, in the 1980s, a slogan minted by the Ministry of Water Resources in Qinghai succeeded in attracting the attention of national leaders, and then popular imagination. “Tibet is China’s Number One Water Tower” was the slogan, an essential mnemonic in a culture much driven by memorable slogans. Tibet at last had a definable benefit for China, specifically for water-short northern China. Other uses for Tibetan landscapes faded, especially pastoral livestock production, which seemed at best inefficient, at worst the cause of degradation. Once Tibet became useful to downstream China, its sole purpose, over a large portion of eastern Tibet designated as Sanjiangyuan , the Three Rivers Source region, was as a watershed.

Having made Tibet, especially eastern Tibet, a watershed, it has now also been designated as a powershed, a similarly naturalised category, full of hydropower energy just waiting to “come out” and race across China to major coastal industries hungry for electricity.

Tibet, as watershed and powershed, reorients the entire plateau, no longer complete unto itself, self-sufficient and sustainable, as it was for thousands of years. Tibet is now defined from a lowland Chinese viewpoint, as a huge area for which a use has at last been found, as source of water and electricity, transfusing the blood vessels of power-hungry lowland China with fresh energy.

[1] Tibet starts constructing the first over-million-kilowatt hydropower station, Kangba TV, 29 April 2016, http://en.kangbatv.com/news/201604/t20160429_2768541.shtml#sthash.XnY5bySt.dpuf

[2] http://en.kangbatv.com/news/201604/t20160429_2768541.shtml#sthash.XnY5bySt.dpuf

[3] Pengfei Wang, Jian Chen , Fuchu Dai et al., Chronology of relict lake deposits around the Suwalong paleolandslide in the upper Jinsha River, SE Tibetan Plateau: Implications to Holocene tectonic perturbations, Geomorphology 217 (2014) 193–203

[4] Bo Li, Songqiao Yao, Yin Yu and Qiaoyu Guo, The “Last Report” On China’s Rivers, Appendix 9.3 p12 https://www.internationalrivers.org/china%E2%80%99s-last-rivers-report

[5] https://library.e.abb.com/public/57af6cb9ca0204ffc1257dcf004d7495/POW0056%20Rev%202.pdf

[6] http://www.energy.siemens.com/co/en/power-transmission/hvdc/hvdc-ultra/#content=Description%20

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xiangjiaba_Dam

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xiluodu_Dam

[9] Fan Xiao, Jinping-I Dam impoundment linked to earthquakes, Probe International, 3 Feb 2014, https://journal.probeinternational.org/2014/02/03/jinping-i-dam-impoundment-linked-to-earthquakes/

[10] Jing Chen, Brian L. Finlayson, Taoyuan Wei, Qianli Sun, Michael Webber, Maotian Li, Zhongyuan Chen; Changes in monthly flows in the Yangtze River, China – With special reference to the Three Gorges Dam, Journal of Hydrology 536 (2016) 293–301

[11] Liu, Zhenya. Zhongguo dianli yu nengyuan) China Electric Power Press, 2012 in Chinese; Translated as: Electric Power and Energy in China, John Wiley, 2013, 139

[12] http://www.chinavitae.com/biography/Liu_Zhenya/bio

[13] China Alleges $1 Billion in Misappropriated Spending, Wall Street Journal, June 16, 2014 http://qz.com/222197/1-billion-went-missing-while-china-was-building-this-electricity-grid/

[14] Global Energy Interconnection: Vision of A World Power Grid, Platts Commodity News, 21 March 2016

[15] Liu, Electric Power, 165-6

[16] Liu, Electric Power, 163

[17] Beth Walker and Liu Qin, China’s shift from coal to hydro comes at a heavy price, China Dialogue, 27 July 2015

[18] China’s State Grid Envisions Global Wind, Solar Network, Wall Street Journal, March 30, 2016

[19] http://www.geidca.com/html/qqnyen/col2015100618/2015-11/06/20151106180517031181362_1.html

[20] Eric Ng , World power: Why China’s State Grid is charged up over global interconnection dream, South China Morning Post, 21 January 2016

[21] Global Energy Interconnection: Vision of A World Power Grid, Platts Commodity News, 21 March 2016

[22] LI Min-na 李敏纳; CAI Shu 蔡舒; QIN Cheng-lin 覃成林;A Study on the Comparison of the Western Land Resource Development between the United States and China, West Forum 西部论坛, Chongqing Technology and Business University 重庆工商大学 2015

[23] WANG Xiuhong, SHEN Yuancun, CONG Richun and LU Qi, Conflicts Affecting Sustainable Development in West China since the Start of China’s Western Development Policy, Sept., 2012 Journal of Resources and Ecology Vol.3 No.3, 202-208

[24] Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

[25] Huang Kaixi and Yu Ning, Debates on Ways to Reform Power Industry Heat Up, Caixin, 10 Nov 2014

http://english.caixin.com/2014-11-10/100749059.html

[26] http://fortune.com/global500/state-grid-7/

[27] Huang Kaixi and Yu Ning, Debates on Ways to Reform Power Industry Heat Up, Caixin, 10 Nov 2014

http://english.caixin.com/2014-11-10/100749059.html

[28] Jianjian She, Chuntian Cheng, Xiong Cheng, Jay R. Lund, Coordinated operations of large-scale UHVDC hydropower and conventional hydro energies about regional power grid, Energy 95 (2016) 433-446

[29] Liu, Electric Power and Energy, 158