When China’s first railway line into Tibet opened in 2006, Tibetans outside Tibet, and their supporters, condemned it, for many reasons. It would only intensify Han Chinese emigration to Tibet, they warned, would disrupt migratory wild animals seeking safe, wolf-free remote pastures to give birth, would cause erosion and degradation, and other disasters as well. There were no counterbalancing benefits.

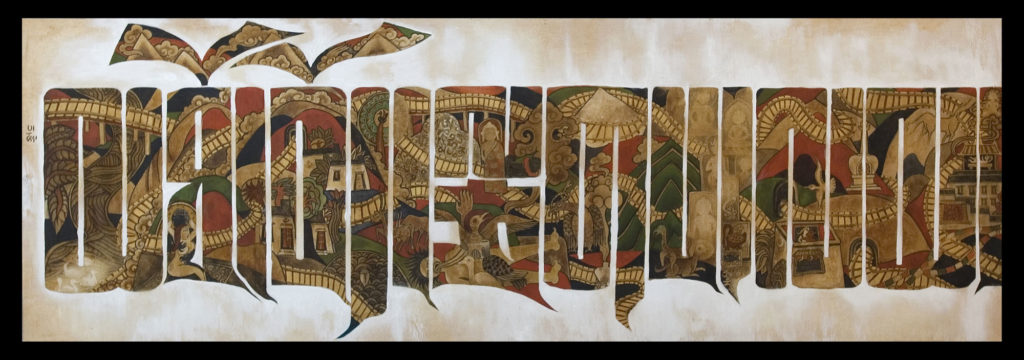

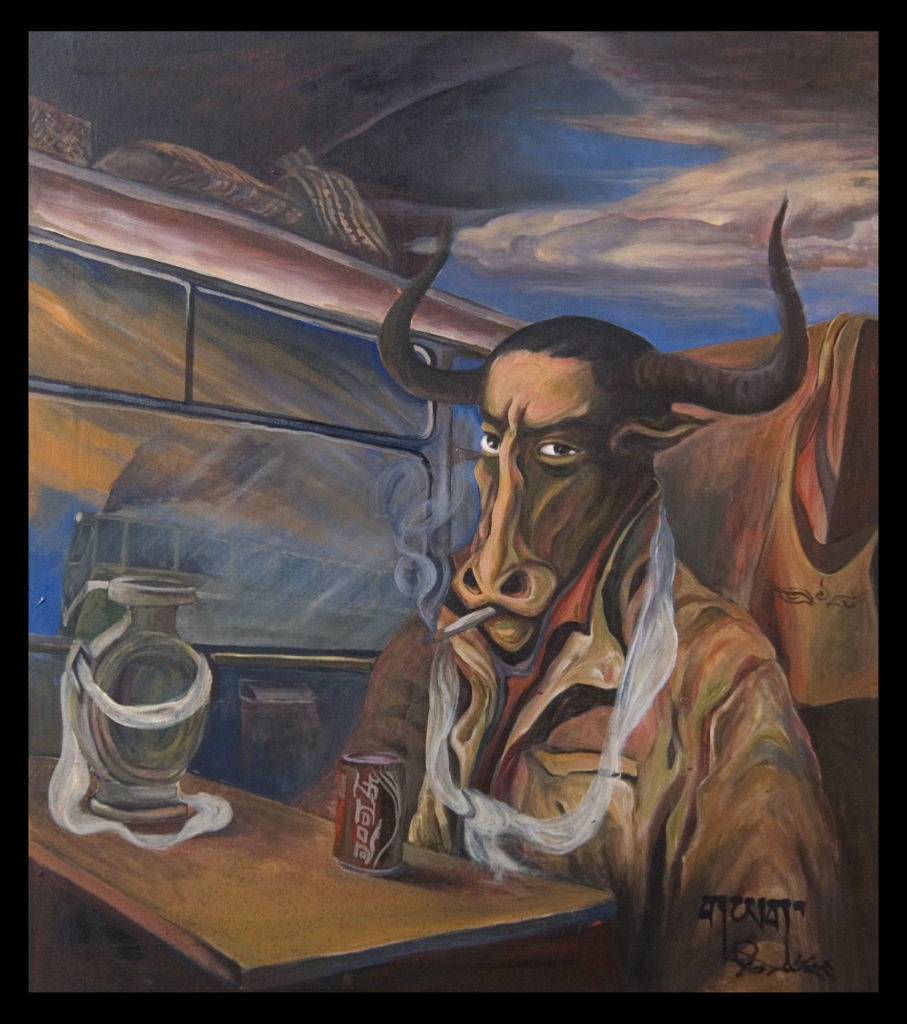

Tibetans inside Tibet took a more nuanced view, if we take the Lhasa 2006 railway art competition as a guide. With the optimism for which Tibetans are rightly famous, the artists responded to the arrival of the chaglam by immediately filling it with Tibetans, arriving and departing, on the move, using it for their own purposes, investing that single track, non-electric, medium speed line with Tibetan characteristics.

China built not only that track but a grand station in Lhasa, its architecture a tribute to the shape of the Potala, and won prizes for its design.

In hindsight, 2006 was almost the last time exile indignation was the automatic, self-evident, default response, in the exile diaspora. If we jump 13 years forward to today, when China is spearing four or five high speed electrified double track rail lines into Tibet, both from the north (from Xining and Lanzhou to Chengdu) and from the east (Kunming to Dechen, Chengdu to Nyingtri and Lhasa) we hear nothing much from exile Tibet. The Tibetan voice has faded.

Meanwhile, inside Tibet, the elaborate dance of appropriation, replication, imitation goes on, at an accelerating pace, as China builds more infrastructure, not only railways and highways, but innumerable museums too, and substantial cities, across Tibet. Who is appropriating whom here? Who is paying homage, who is ripping off the original, with a bad fake?

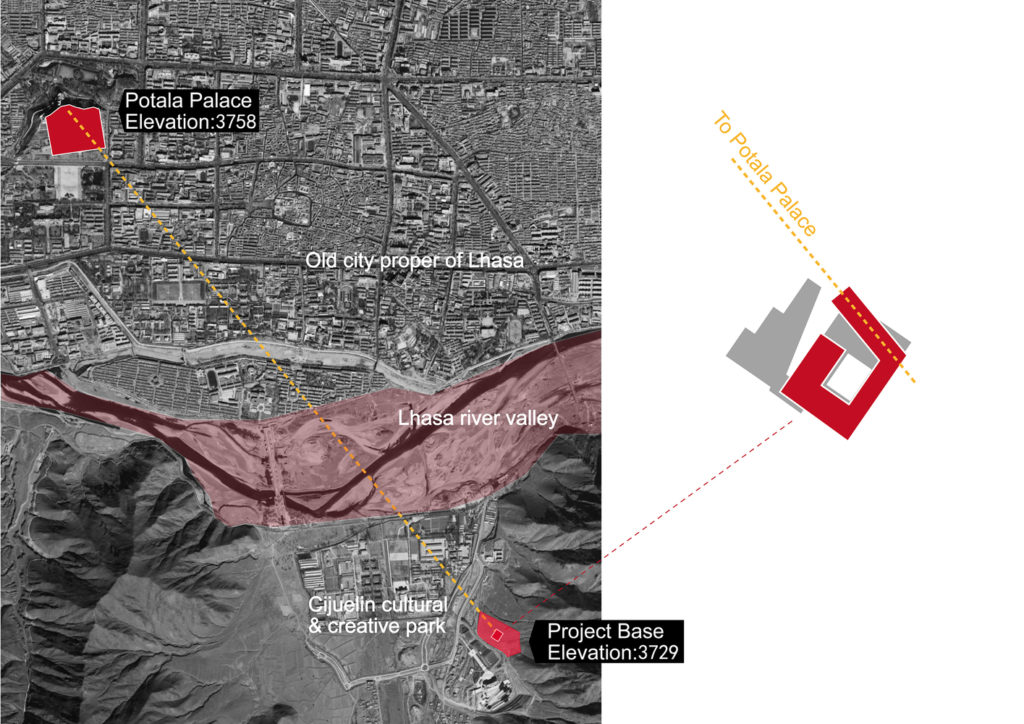

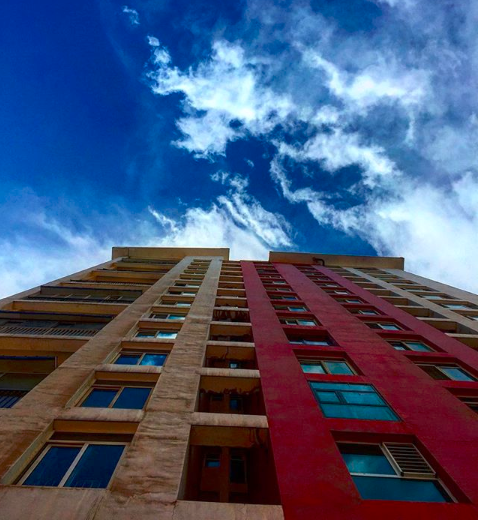

When China builds a faux Potala 布达拉宫, across the Kyichu, high on the south bank, high enough to gaze directly at the original, is this Tibetan architecture with Chinese characteristics, or Chinese architecture with Tibetan characteristics, or something else altogether? What to make of this Tibet Museum of Intangible Cultural Heritage?

Little wonder, in the face of such accelerating construction, Tibetans are increasingly speechless. The old categories, when it was clear who is the victim and who the victimiser, no longer apply so readily.

ASCENDING TO THE HOLY LAND

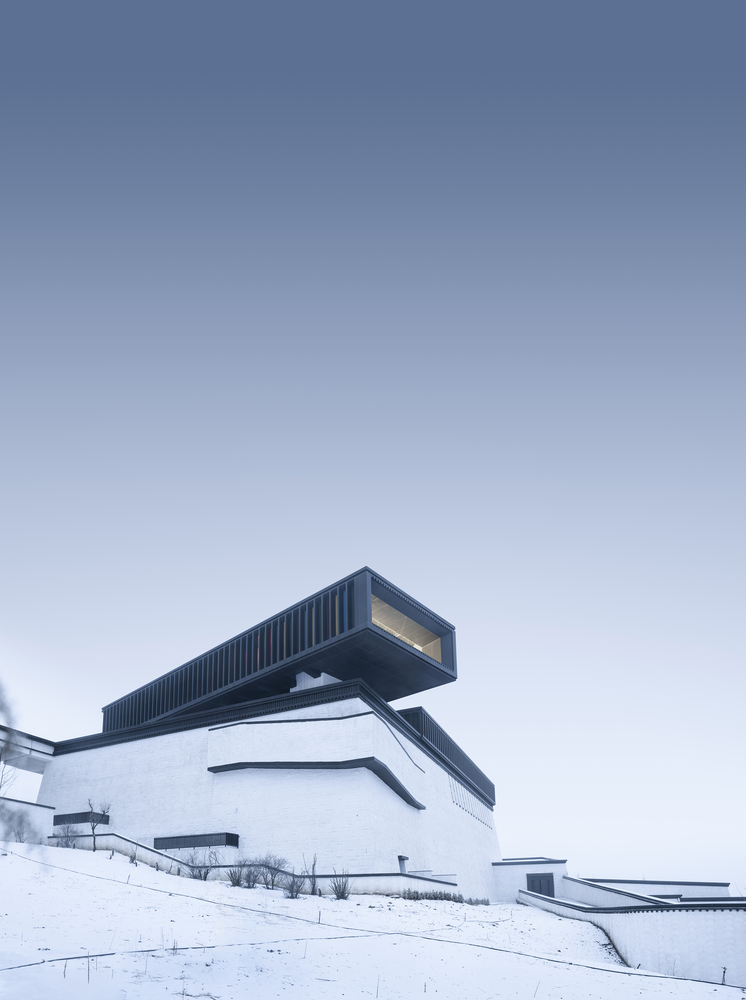

The Shenzhen based architects, keen to show off their ersatz Potala, lapse into extravagant rhetoric. The architects of the new Tibet Intangible Heritage Museum fixate on the Potala steps: “Tibet is considered to be a holy place close to the sky, with the Potala Palace and Jokhang Temple being pilgrims’ destinations. So, our basic design concept of Heavenly Road is consistent with the most unique natural and cultural genes here.”

The ascent matters. The climb to the Potala, or to the Chinese and Tibetan Buddhist pilgrimage mountains such as Emei Shan and Wu Tai Shan, are more than an exertion. They are opportunity to pause, to reflect, to contemplate why you are doing it, what expectations, what baggage you bring with you. Tibetans pray to be reborn in Potala, that hidden land, from where it is a short journey to enlightenment.

The architects fanciful “design concept” of the Potala steps as heavenly road, Tiān lù 天祿, is no accident. This is a favourite Chinese metaphor for Tibet, at an altitude so high you can touch the clouds, to invoke yet another cliché. Tianlu was also the default metaphor for that initial rail line into Tibet, and amplified by the pop songs that made love to a railway.

The architects boast to fellow architects: “After appreciating the rich intangible cultural heritage of Tibet through a hard climb, visitors will finally reach the ending point where they can overlook the Potala Palace across both time and space, establishing a dialogue as well as paying a tribute not only to Tibet’s great natural landscapes, history and culture, but also to the holy land at the bottom of everyone’s heart.”

It is easy to respond to such words with outrage, exacerbated when you look at their many pictures and design graphics, which manage to combine the exterior of the Potala with the interior of the Jokhang. A mashup of the two holiest buildings in Tibet. That could tempt us to fall back into the certainties of identity politics of the vanished decades of Tibet advocacy. Self-reinforcing outrage gets you nowhere these days, there is just too much of it about, wherever you look.

But it is hard not to be outraged, when the architects boast that: “Secondly, it means a unique experience of space. The main volume of the museum evolves from the main hall of the Jokhang Temple, forming an introverted and stable space. The touring path of the “heavenly road” put up in such a space creates a diversified spatial experience that makes people feel tall, narrow, spacious, dim, or bright in different public spaces or exhibition chambers, and indicates an reflection of a special journey of life.”

Faced with such nonsense, the habitual response is to label this new Potala a fake, reproducing a neat binary of categories, the authentic and the fake. It’s all too neat.

CHINA’S ORIENTALISM

The fifty or more shades of grey in between suggest this burbling about Tibet as the land of magic and mystery, a re-tread of the Western fantasies of Shangri-la a century back, are more than burble, and are increasingly heartfelt. No longer just a marketing pitch, nor simply a propaganda ploy, today’s China knows in its bones that Tibet has something China lacks, something valuable, even life-changing. Today’s new era China may lack the vocabulary for what that elusive something is, and so fall back on clichés, but the appreciation is growing, wherever you look in Chinese popular media. It was way back in 2002 that Michelle Yeoh climaxed her movie The Touch, 天脈傳奇,Tian mai zhuan qi, on the roof of the Potala, its martial arts heroes attaining mystical revelation.

No contemporary architect could be content with just mashing the Potala and Jokhang. This replica Potala might look much like the original from below, but the higher you go, the more modern, even edgy, it gets, culminating in a box on top, not deer and a dharmachakra turning of the wheel in remembrance of the Buddha’s first teachings. That box, draped in lungta windhorse colours, is set at a gravity-defying rakish angle. It signals the triumph of modernity, the capacity of engineering to cantilever structures out into open space. This is past and future somehow meshed, a melange of styles, at once Tibetan, Chinese and global anywhere, which makes it very now.

Worries that China might build an imitation Potala, in the new industrial zone south of the Kyichu, go back years. Public intellectual Woeser back in 2014 called out the first attempt at Tibetanesque design, built to stage the propaganda opera, a must-see for Han tourists, on how princess Wencheng, back in the T’ang dynasty, brought civilisation to the barbarians of Tibet.

This Rukor blog, back in 2014, attempted to complexify the issue, by introducing the Chinese concept, alien to either/or Westerners, of the “authentic replica.” To the ears of most English speakers, that is an oxymoron, a self-contradictory concept. You can be authentic, you can make a replica, but you can’t be both. In Chinese, it is not odd. For example, some of China’s minority ethnicities are able to control the inrush of Han mass tourism by building replica folk villages where, when the buses roll in, they dress in replica folk costume and stage replica folk dances. That way where they actually live is separate, not submerged under the tourist tide. Everyone gets what they want, the tourists are happy with the staged authentic replica, the locals can get on with their lives, not mixing up performance with living.

OVERWHELMED BY THE TOURIST MASSES

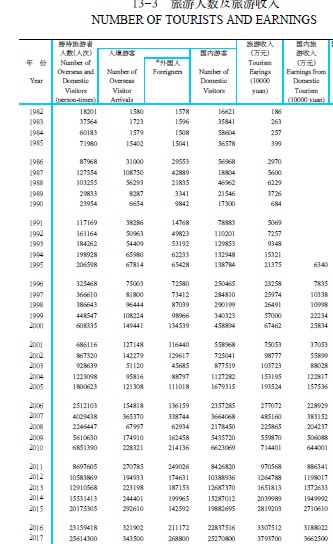

Tibetans have no control over tourism, and the numbers arriving have swollen way beyond the capacity of the Potala or Lhasa generally, to accommodate the 25 million Han coming each year, on the latest official statistics (multiply the numbers in the right column by 10,000). Since almost all Han go to Lhasa, that is a huge overload, and a strong argument for a replica Potala, aka Tibet Museum of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

But handling the waves of curiously incurious Han masses is only part of the wider story of speedy urbanisation throughout Tibet, of the push and pull that magnetises Tibetans towards urban comforts and facilities; plus the objectification of Tibetan-ness as the unique selling proposition that makes urban Tibet a marketable destination.

Rapid urbanisation and a veneer of Tibetan characteristics go together. Much of inner Lhasa has been demolished and rebuilt with Tibetan finishes, external facades that nod to traditional building design, because mass urbanisation and mass tourism demand that Tibet, as an attractive destination, be both familiar and different, comfortable yet exotic, safe but also edgy, heated, airconditioned, even pressurised yet also raw, authentic and even challenging. That’s the mix, and the authentic replica, to which you go by comfy bus, fits those needs.

We could dismissively call all this fake, or, a bit more elegantly, Tibetanesque or Tibetoiserie. We could call it China’s own Orientalism, a fantasy of packaged, sanitised difference that tames Tibet, put under glass, fashioned as museum display.

However, the Tibetan artists who, in 2006, Tibetanised the railway, reminding us that it opened the way for Tibetans to go round China, tell us there is more to this. Who is taming whom? Are the Tibetans, slowly, almost imperceptibly, taming the minds of the Chinese, insisting quietly but persistently on being different, not just in architecture but in understandings of the nature of mind, the purpose of life?

THE LONG GAME

The game of Tibetan-Chinese relations is an old one, both sides have accumulated innumerable strategies for dealing with each other. The question of who is appropriating whom is an old one. The Buddhisms of Tibet and China are the same and different. The traditional healing systems overlap yet are different. The traditional architecture of monasteries is similar but different. Relations between charismatic Dalai Lamas and powerful Chinese emperors were full of projections, patronage, appropriation, subtle jostlings as to who sits highest, competing courtly chronicles, elaborate gift giving and bestowal of extravagant titles, proclamations of control without substance, the rule of men not law.

Tibetans know how to do such ambiguity. Princess Wencheng is a good example. For centuries, she was forgotten in China. It was the Tibetans who kept alive her memory, revering her not for introducing seeds, agriculture and civilisation to primitive Tibet, but because she brought the Jowo, the most sacred of all Buddha statues, to Tibet. It was through the Tibetans that China rediscovered their long forgotten princess and the power of the Tibetan empire to demand a princess to marry the king of Tibet. The opera Gyasa Belsa tells the story, with all the flourish of classic Tibetan art.

That was then reverse engineered into a vehicle for making China not the tribute payer but the civiliser, benevolently sending their princess to the outer darkness to civilise the Tibetans. To stage this revisionist Sinocentric drama, China then built the pseudo Tibetan backdrop that so horrified Woeser, to make the staging appear authentic. Is Songtsen Gampo’s Chinese bride the origin of China’s Tibet, or Tibet’s China?

TRIBUTE OR RIPOFF?

Let’s look at this from a different angle. Take the China International Music Competition, a prestigious effort by China to get into the big league of Western classical music performance. China embraces the canon of European classic music, much as it now embraces Tibet as a land of mystery and revelation. There is now a massive investment in training and fostering talented young Chinese pianists, not only to attain technical mastery but to play with passion and depth, like the most celebrated of Western performers.

How does that fit with China’s insistence on everything having mandatory “Chinese characteristics”? For a century, the slogan has been that anything Western must serve China, and Xi Jinping recently reminded everyone that still holds.

Yet the reality, to quote the Financial Times, is that: “China boasts over 80 orchestras, many of them new creations. Concert halls are typically full with young audiences. In particular, the nation is gripped by piano mania, with an estimated 40m children learning to play the instrument. Competitions are springing up all over China, many of them organised by conservatories. Their aim is to raise quality and prestige by drawing students hungry for solo careers. The rivalry is intense. Such events are lavishly funded by the government. ‘The government is using music to purify the souls of the people,’ Wang Liguang, an influential Chinese Communist party member explains via a translator. ‘This is the message that we send to the world: that we are nurturing our local traditions but harnessing the essence of the advanced western culture to make Chinese culture shine more brightly.’”

So who is appropriating whom? Is this imitation, or ripoff, or heartfelt homage? Is China’s romantic image of Tibet, so reminiscent of Western Shangri-la fantasies, just a mass marketing ploy to get even more than 25 million Han into Lhasa each year? Does China grasp that if Tibet becomes the same as anywhere in China, much is lost, much that will be a loss for overworked, overcompetitive urban Han? Is this a quiet reassertion of Tibetan difference, fostered wherever possible by Tibetans, attuned to the unmet higher needs of speedy Han apartment dwellers?

Is the new Potala, gazing across the Kyichu at the original, just a cynical knockoff, or also a homage?

TANGIBLE AND INTANGIBLE

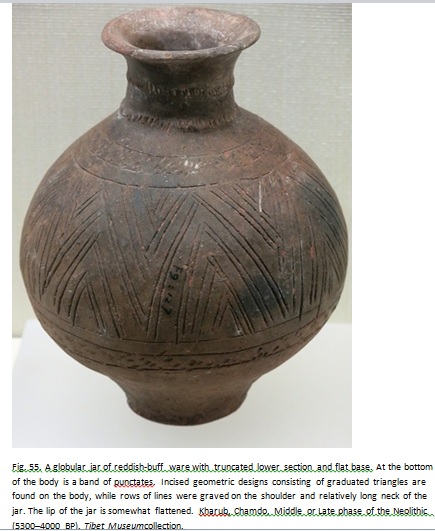

Beyond the pseudo Potala façade, the interior is meant to display Tibetan intangible cultural heritage, in contrast to the Tibet Museum in Lhasa, which displays tangible cultural heritage, such as Chamdo pottery that is several thousand years old.

The odd distinction between tangible and intangible heritage is not of China’s making, but of UNESCO. When UNESCO got World Heritage under way in the 1970s, there was a Eurocentric bias towards monuments and ruins. They are tangible. Culture that merits celebration as heritage worth protecting is much more than monuments; so UNESCO came up with the vague and clumsy category of intangible heritage. Sowa rigpa disease diagnosis and treatment, for example.

MUSEUMS EPITOMISE URBANISATION

The furious pace of museum construction, across Tibet and across the whole of China, is part of the making of cities, and a civilised urbanisation that keeps the past present, but under glass and under official control of interpretation.[1]

It is the pace of urbanisation in Tibet that is by far the biggest transformation Tibet has experienced, in thousands of years, and yet it is little discussed. Urbanisation in Tibet has profound consequences, such as negating minority ethnicity autonomy, as geographer Emily Yeh and anthropologist Charlene Makley have recently pointed out:

“The urban today is thus privileged in China as the site of progress and modernity, the imaginative horizon of the future, and a synonym for development itself. Planners take urbanization to be the central means for continued economic growth and modernization. At the same time, urbanization is also a key process for reproducing state power. As geographer Tim Oakes notes, China appears to be taking to heart Henri Lefebvre’s argument that the ideology of urbanism has replaced that of industrialization as the medium of history and progress. Thus, as Oakes put this, “The state in China reproduces itself in urbanism, not merely by constructing cities, but in the way the state is restructured and reorganized in the form of urban institutions.”

“The significance of the urban as both the inevitable site of dreams of future prosperity as well as the locus of state power is both underpinned and reinforced by China’s territorial administrative hierarchy, which structures subnational territory and ranks administrative divisions. Five of six prefectures of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR) have been converted to urban prefecture-level municipalities, and two rural counties of Lhasa Municipality, the capital of the TAR, have recently been converted to urban districts, a process that involves substantial farmland expropriation and the displacement of people from rural villages to high-rise apartment blocks. The TAR government plans to raise the provincial urbanization rate from 25.7 percent in 2014 to over thirty percent by 2020. Outside of the TAR, a number of rural Tibetan counties (including Yulshul in Qinghai Province, Dartsedo and Barkham in Sichuan Province, Shangrila in Yunnan Province, and Tso in Gansu Province) have also been upgraded to county-level cities over the last decade. Importantly, urban administrative units are ethnically unmarked; cities do not have “autonomous” status and associated cultural and political rights. Mongolian scholar Uradyn Bulag has argued that as a consequence the administrative promotion of rural counties to urban municipalities is a “shortcut to overcoming ethnic autonomy.” [2]

Accelerating urbanisation stacks Tibetans in high rise apartment blocks, under surveillance, with no land for animals or even a vegetable greenhouse. Urban life means trips to the countryside, to collect the tangible herbal ingredients to make sowa rigpa medicines become rare. Sowa rigpa is instead under glass, at the Potalesque Tibet Intangible Heritage Museum, a feature attraction of post-autonomy urbanism. The tangible becomes intangible, autonomy fades away, urban density and grid management replace the open range.

Maybe it is time to focus on

urbanisation, beyond the Tibetan

characteristics of the architecture of museums and railway stations in Lhasa.

[1] Tami B l u m e n f i e l d and H e l a i n e S i lverman eds, Cultural Heritage Politics in China, Springer, 2013

[2] Emily T. Yeh & Charlene Makley (2018): Urbanization, education, and the politics of space on the Tibetan Plateau, Critical Asian Studies, 50, 4, 2018