TIBET 2021: WHAT CAN WE EXPECT?

Blog one in a series on Tibet in 2021 1/7

Fifteen years ago one of the favourite slogans of central planners was to declare Tibet would under go “leap-style development.”[1] At the time, it wasn’t clear what this meant. The phrase had disturbing echoes of the Great Leap Forward that caused the greatest famine Tibet has ever known.

Now we do know. Tibet is in the midst of accelerating development, industrialisation, urbanisation and globalisation. Tibet finds itself at the forefront of blockchain production, new electric vehicle lithium mining, the solar and wind power boom, even computer chip silicon manufacture. Tibetans were never asked about any of these Anthropocene accelerations, nor informed they exist in their midst.

These exploitations of Tibetan landscapes, resources and common pool resources are set to intensify further in 2021.

So this blog focuses on several Chinese plans, as the 14th Five-Year Plan for 2021 to 2025 is about to roll out. Among the topics explored in depth:

- The new proletariat of Tibet, set to be redeployed

- Hydropower, solar and wind power in Tibet

- Extraction of copper on a globalised scale

- The 2020 Census in Tibet

- 14th Five Year Plan and Goals for 2035

- Biodiversity and climate global conferences

- Disinformation and securitisation

- Elite debates on future directions for Tibet

LOOKING BACK TO LOOK AHEAD

This blog, a year ago, attempted to list the likeliest developments in Tibet. Two major developments we didn’t see coming: the corona virus and the August 2020 Tibetwork Forum. Months later we still don’t know much about the specific directives issued by the Tibetwork Forum as neican, for insiders only. We do know the headline, that, as with everything else, the CCP is correct, has been correct, and always will be correct.

We do know that we need to know those secret directives. We know now that China’s shift, in Xinjiang, to a strategy of total demobilisation and incarceration dates back to Xi Jinping’s tour in 2014. His directives took years to instal before the mass incarcerations began. We seem to be in that interval, akin to Xinjiang between 2014 and 2017, when the party-state mobilises all party mass organs and all government departments, to launch a full campaign to forcibly “civilise the barbarians”. The whole purpose of any central work forum is to launch a campaign, drawing in the whole of government and party, to storm the bastions of resistance. Government by campaign is hardwired into CCP history.[2]

So a lot hangs on what the secret directives issued by the 2020 Tibetwork Forum say. Right now, we don’t know. Such documents do leak.

Also we will see, in legislative sessions of the provincial assemblies of TAR, Qinghai etc, formal establishment of measures that implement Work Forum diktats. What is at stake is the core question, signalled by the deep dive into official procurement and recruitment sites, by Adrian Zenz, that China is gearing up to do in Tibet something akin to Xinjiang.

Yet lots of campaigns fizzle out. Tibet is not Xinjiang. In Xinjiang the official narrative was all about terrorism, a simple good-versus-evil story, that just doesn’t in any way apply to Tibet. The rationale for extending coercive assimilation programs to Tibet targets the growing population of displaced nomads, expelled monks and nuns, and other Tibetans marginalised by securitised interventions into their lives, including former prisoners, and the tortured. These are the outsiders of contemporary Tibet, sometimes unable to find a place in Tibetan society because they are under intense pressure to spy and inform on fellow Tibetans, or face re-arrest.

These Tibetans are the new proletariat. Tibet historically never had a lumpen proletariat, because everyone belonged somewhere, cities were nonexistent, towns few, slums barely noticeable. In rural areas, everyone knew rich and poor can exchange places, your herd can be wiped out overnight by an unseasonal snowstorm. The poor usually would be given or loaned animals to rebuild herds after a disaster. Nomads were entrepreneurs, running businesses of modest or considerable scale, juggling seasons, grazing pressure, loans, trading caravan journeys of months, arbitraging supply here and demand there.

China has never recognised the millions of drogpa nomads as entrepreneurs skilled in managing unpredictable seasons. For decades, their many skills have been unrecognised, their stewardship of landscapes unnoticed. The entire rural population is officially classified as “surplus rural labourers”, as if they tramp about aimlessly, looking for work.

Given those assumptions, it was only a small step to blame the nomads for patches of black soil, and remove them to urban fringes, and badge them “ecological migrants”. From there it is but a small further step to classify them as an unskilled rural proletariat lacking vocational skills and fluency in the only language that opens the door to success: standard Chinese. The number of nomads required to relocate to towns, usually along highways leading into the growing Chinese towns and cities, has steadily grown for decades.

Something must be done with them. They have shown little interest in becoming Chinese, so the pace must be forced. The parallels with Xinjiang get stronger. For the security state it is not hard to define them as a security threat, especially in areas close to international borders.

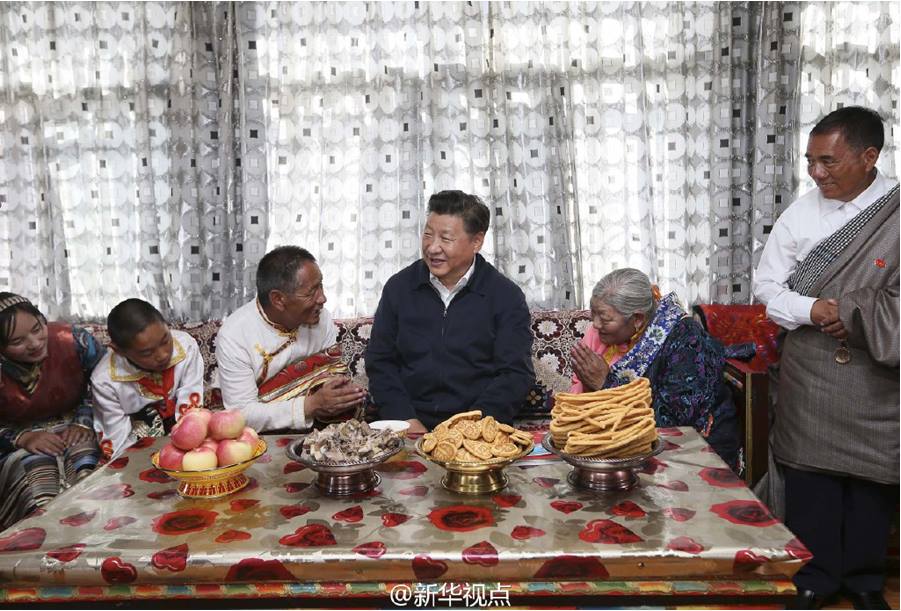

If it took three years in Xinjiang, from 2014 to 2017, from Xi Jinping’s instruction to build “walls made of copper and steel” 铁壁铜墙 铁壁铜墙 and “nets spread from the earth to the sky” to capture terrorists. We are now four years on from Xi Jinping’s 2016 inspection tour of Qinghai, including the Tibetans relocated to the outskirts of Gormo.

China needed three years, not only to build the “re-education” lockdown centres surrounded by razor wire and watch towers, but also to capture the DNA of each Uighur, and facial recognition data fed into big data algorithms, to decide who were the greatest security risks. Collecting the DNA and facial profiles of Tibetans is largely complete. Each Tibetan can be assigned a risk rating.

So Adrian Zenz’s warning that China is gearing up to do in Tibet something akin to what it does in Xinjiang is plausible.

[1] Hu Angang and Wen Jun, The Problem of Selecting the Correct Path for Tibetan Modernisation (Part 1). China Tibetology, 2001, 1, 3 – 26

Xu Min-yang ed., Tibet Autonomous Region Urban Economic Development Studies, Tibetan Economics Society, 2004

[2] Xin Sun, Campaign-Style Implementation and Affordable Housing Provision in China, China Journal #84, July 2020