What is really happening in protected areas in China

BY ENVIRONMENT DESK OF TIBET POLICY INSTITUTE, INDIA

For IUCN World Parks Congress 2014

When a government declares an area protected that’s good.

When state power draws a red line round a large area, designating it a nature reserve, that’s good, right?

Not always. What seems on paper to b e another step in protecting the planet is actually meaningless if, within that red line, miners are allowed in, while authority looks away. That’s bad. That’s what is happening in many of the biggest protected areas in China.

What seems on paper to be protection for all sentient beings is the direct cause of poverty, immiserisation and destitution when the indigenous stewards of the land are forced to lose their livelihoods and leave their ancestral lands, without any consultation. That’s what is happening today in Tibet.

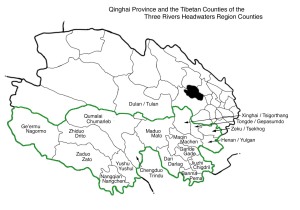

Tibetan nomadic pastoralists are being excluded, without say, en masse, from a huge area of prime pastoral land, in “the second largest nature reserve in the world”, that includes four entire prefectures, more than half the area of Qinghai, a big province, in the name of conservation. Rather than including the pastoralists in solving problems of watershed protection and land degradation, hundreds of thousands of skilful Tibetan pastoral nomads are losing their livelihoods, officially designated as “ecological migrants.”

IUCN classifies the 363,000 sq kms of the Sanjiangyuan Nature Reserve (SNNR), on its protectedplanet.org database as WDPA315729, home to 100 iconic species, a few of which are classified as endangered. China classifies this vast green pasture as its “number one water tower”, because both of China’s great rivers, the Yangtze and the Yellow (and the Mekong of SE Asia) all rise in Tibetan glacial peaks, then meander all the way through these great grasslands. China, short of water after decades of over-use, has now decided its access to upstream sources is best guaranteed by depopulating the best grazing lands of the entire Tibetan Plateau, and IUCN seems to uncritically agree.

IUCN, on its global database of protected areas, cuts and pastes from Wikipedia: “To protect the grasslands, pastoralists are not permitted to graze their animals in designated ‘core zones’, and grazing is supervised elsewhere in the SNNR. In addition, residents have been resettled from core zones and other grassland areas of the  SNNR, and rangeland has been fenced and is in the process of being privatized throughout the Sanjiangyuan Area.”

SNNR, and rangeland has been fenced and is in the process of being privatized throughout the Sanjiangyuan Area.”

The Wikipedia article provides no source for the above statement, which is not a scientific assessment but a summary of China’s official stance.

This narrative makes China look good, and the nomads problematic, irrational and backward abusers of the common pool grassland resource. In reality Tibetan nomads have cared for these lands for 9000 years, the archaeologists say, accumulating deep knowledge of sustainable grazing practices that maintain biodiversity, natural values, carbon capture and water quality.[1]

Worldwide, IUCN encoura ges local community engagement with conservation, and indigenous knowledge as a primary asset in achieving conservation outcomes. Yet, on the Tibetan Plateau, where communities have no opportunity to organise their own NGOs, officials have decreed, since 2003, a policy of tuimu huancao, closing pastures to grow more grass. This shows China does not understand how grazing economies work, by balancing livestock grazing pressure with the growth cycle dynamics of indigenous grasses and sedges in the cold Tibetan climate.[2] China says: “there is a contradiction between grass and animals.”[3] The more grass, the fewer possible animals; vice versa, the more animals you have, the less is the grass. This means you cannot have both, it is a zero/sum logic. That is a fundamental misunderstanding of pastoralism, as practiced anywhere worldwide.

ges local community engagement with conservation, and indigenous knowledge as a primary asset in achieving conservation outcomes. Yet, on the Tibetan Plateau, where communities have no opportunity to organise their own NGOs, officials have decreed, since 2003, a policy of tuimu huancao, closing pastures to grow more grass. This shows China does not understand how grazing economies work, by balancing livestock grazing pressure with the growth cycle dynamics of indigenous grasses and sedges in the cold Tibetan climate.[2] China says: “there is a contradiction between grass and animals.”[3] The more grass, the fewer possible animals; vice versa, the more animals you have, the less is the grass. This means you cannot have both, it is a zero/sum logic. That is a fundamental misunderstanding of pastoralism, as practiced anywhere worldwide.

Since 2003, China’s steady implementation of its policy of displacing populations in the name of conservation[4] has made hundreds of thousands of nomads redundant, dependent on official handouts, leading marginal existences in peri-urban concrete settlements, often far from their pastures.[5] In most cases they are forbidden to return to livestock production, even when the grazing bans technically are for three or five year experimental periods. They are seldom given training in modern skills, and their traditional knowledge of rangeland dynamics is ignored.[6]

IUCN appears to have made a grievous mistake. IUCN elsewhere has a good record of championing indigenous knowledge and traditional community practices as beneficial for biodiversity conservation. IUCN has frequently published reports and guidelines on how to include local communities in the management of protected areas. Yet in this huge heartland of Tibetan pastoralism, bigger than the UK, nomad voices have been forcibly silenced,[7] leaving only the official voice insisting the exclusion of people is an objective scientific necessity.

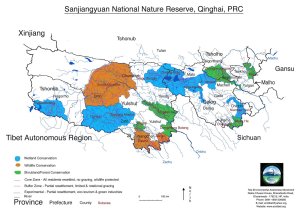

IUCN MAP OF SANJIANGYUAN PROTECTED AREA, AND ALL PROTECTED AREAS IN CHINA, MOST OF WHICH ARE ON THE TIBETAN PLATEAU

WHY IS THIS WRONG?

- Excluding the custodians of the land who have intimate knowledge and millennia of experience in sustainable management is a net loss of successful curation of whole landscapes that can never be replaced by the current reliance on GIS satellite data and a handful of research stations.

- Tibetan nomads never fenced their land, allowed wildlife herds to mingle freely with domestic animals, their annual migration unhindered. Only since Tibet came under China’s active control since 1960 has biodiversity plummeted.

- Past policy failures are unmentionable, shifting the blame for land degradation onto nomads.[8] State failures since 1960 include communisation, compulsory fencing, allocation of land to small family units rather than larger and more flexible traditional tent-circles of many families pooling herds. Rigid stocking rates and carrying capacity regulations have restricted nomads to staying in their fenced winter pastures year-round, putting excessive pressure on small areas, with resulting degradation, which also made nomads poorer.[9]

- The Tibetan Plateau, traditionally highly self-sufficient in food production is now rapidly losing food security, relying instead on imports from distant Chinese cities. At a time when food insecurity is a global problem, taking such a big area out of livestock production is folly.

- Grazing land from which yaks, sheep and goats have been removed, along with the herders, reverts to unproductive shrubland. Biodiversity reduces as grazing pressure no longer cuts the taller grasses, allowing shorter medicinal plants to flourish in the sward.[10] Scientific research shows that China’s “close pasture to grow more grass” policy is failing to attain its stated objectives.

- Mining has proliferated in protected areas, often with the connivance of corrupt local officials. Far from protecting degraded land, official designation of protected areas in Tibet effectively removes the local protectors and allows illegal mining companies in, who further destroy the “fragile ecology” of Tibet. In 2014 the Chinese Communist Party’s anti-corruption squads have many times singled out mining in Qinghai province as an epicentre of corruption. The Sanjiangyuan Nature Reserve is half of Qinghai.

- Land tenure rights allocated by the state to nomad families in the 1990s have been abrogated. Often Tibetan families have to surrender their land tenure certificates, even though, when they were issued, they were promised long term land security, as were China’s farmers. In China, perversely, forest dwellers are now gaining better land tenure, while rangeland dwellers are losing theirs.

China buys agricultural land worldwide to meet the accelerating demand of its people for protein; while wasting the best productive Tibetan land. China has discovered a taste for milk, yet Tibet, where dairy products are the main marketable surplus, plays almost no part in meeting urban China’s demand for dairy. The potential benefit of linking the Tibetan economy to modern China has not been realised.

China has designated huge portions of the Tibetan Plateau as protected. Over half of all the protected area in China is on the Tibetan Plateau. China says 1.557 m sq kms are protected. On the Tibetan Plateau, in the 150 counties officially designated as areas of Tibetan ethnicity government, protected areas are 770,000 sq kms. Of that total, nearly half is the Sanjianyuan Nature Reserve of nomad exclusion.

China is praised worldwide for setting aside so big a protected area, offsetting criticism that China is the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitter, consuming more than half the global coal use each year. China wins points carbon capture by excluding human use and grazing, without evidence that over the long term the net carbon balance is improved.

IS THERE A BETTER WAY?

The nomads of Tibet need not be dismissed as the ignorant source of land degradation. They can be, and want to be part of the solution. Removal of human populations should be the last resort, but in China efforts to rehabilitate degrading rangelands have been sporadic, half-hearted and inconclusive.

The methods IUCN advocates are the answer. Co-management, based on empowering pasture user groups, a partnership of government and the local communities, is the way ahead. This has been proven, many times, around the world, and IUCN has often documented such successes. Instead of fencing nomads out, employing them to re-sow native grasses and tend disturbed areas, under scientific guidance, brings together agricultural extension science, biodiversity ranger employment and poverty alleviation in one package, that results in REDD+, the reduction of degradation and deforestation through payment of local communities for the ongoing environmental services they provide, especially to China’s downstream urban masses.

Climate change makes inclusion, not exclusion, more urgent. The Tibeta n Plateau, like the poles, experiences climate change at an especially rapid pace, with earlier spring melting permafrost and draining ice in the soil before plant roots can reach it as the short growing season begins, well before the monsoon rains arrive. As a result, many Tibetan wetlands have been drying and shrinking, which threatens migratory species reliant on the wetlands. Several wetlands, including those with Ramsar listing, were drained at China’s insistence in recent decades, further accelerating the desiccation of these key areas. Much work is now needed to fill the drainage ditches, which also reduces methane gas emissions and peat fires, especially in the Dzoge wetland, a 500 sq km Ramsar site on the Yellow River just east of the Sanjiangyuan Nature Reserve. Poor Tibetans need employment, and land rehabilitation, if done well, is often labour-intensive. IUCN can help persuade China there are better alternatives than exclusion, depopulation and the outdated “tragedy of the commons” argument.

n Plateau, like the poles, experiences climate change at an especially rapid pace, with earlier spring melting permafrost and draining ice in the soil before plant roots can reach it as the short growing season begins, well before the monsoon rains arrive. As a result, many Tibetan wetlands have been drying and shrinking, which threatens migratory species reliant on the wetlands. Several wetlands, including those with Ramsar listing, were drained at China’s insistence in recent decades, further accelerating the desiccation of these key areas. Much work is now needed to fill the drainage ditches, which also reduces methane gas emissions and peat fires, especially in the Dzoge wetland, a 500 sq km Ramsar site on the Yellow River just east of the Sanjiangyuan Nature Reserve. Poor Tibetans need employment, and land rehabilitation, if done well, is often labour-intensive. IUCN can help persuade China there are better alternatives than exclusion, depopulation and the outdated “tragedy of the commons” argument.

Which human rights are infracted by China, with IUCN’s rubber stamp, depopulating the great grassland of eastern Tibet?

- The right to food and food security

- Right to land and secure land tenure

- Right to livelihood, income and self-employment

- Right to free speech and assembly, routinely abrogated when Tibetans protest displacement and invasive resource extraction, invariably suppressed violently by state power

These repeated rights violations flout the good work IUCN does worldwide and the approach to conserving the planet IUCN consistently advocates as the right path. These violations have been well known for years, despite China’s efforts to silence Tibetans and forbid external scrutiny. In 2007 Human Rights Watch published an analysis of nomad removals, telling titled No-one has the Liberty to Refuse.

The most recent fieldwork report comes from Chinese ethnologist Qi Jinyu: ”The local people reckon that their behaviour does not cause overgrazing, but although they don’t agree with the official theory of overgrazing, they nonetheless had to submit to the state’s decision to proceed with migration and create a ‘no-man’s land’ wilderness protection zone.”[11]

China has been questioned many times at the UN over the immiserisation of nomads. China’s 2014 haughty official response to UN special rapporteurs is that: “China’s nomadic pastoralists have been following a lifestyle of moving from place to place in search of water and grass for the past several thousand years; this kind of lifestyle is characterized by instability; not only does it adversely impact their productivity, but it also influences their lives. Appropriately settling them could change their lifestyle, not only benefiting the development of production but also helping these nomadic pastoralists to further develop themselves and enjoy modern civilization. The specifics of where to settle them and by what means should be scientifically designed and comprehensively arranged by the local government.”

Specifically focussing on the Sanjiangyuan protected areas, China tells the UN it is “organizing the transfer of human populations from the Sanjiangyuan core region for ecological purposes, thereby protecting and restoring the region’s ecological function, and encouraging sustainable development and harmony of humans and nature.”

The Himalaya and Tibetan Plateau is warming three times faster than the global average. Tibet is on the frontline of global climate change. This is not the time to exclude those who can replant and rehabilitate degrading areas, by including them in the design and actual work of repairing damage done by past state failure and accelerating climate change. The Tibetan Plateau, close to two percent of the land surface of our planet, needs all the help it can get. Exclosing people from protected areas should be the last resort, after all other methods have been tried. In China, it is the first resort a social engineering solution to a problem that originates in state policies that over recent decades concentrated both Tibetan nomads and their herds on smaller land allocations, removing much of their customary seasonal mobility, the key to reducing grazing pressure and preventing degradation.

[1] Georg Miehe, Sabine Miehe, Knut Kaiser, Christoph Reudenbach, Lena Behrendes, La Duo, Frank Schlütz; How old is pastoralism in Tibet? An ecological approach to the making of a Tibetan landscape: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 276 (2009) 130–147

[2] National Research Council, Grasslands and Grassland Sciences in Northern China, Washington, National Academy Press, 1992

[3] BAO Fenglan A Study Of The Countermeasures Of Optimizing Animal Husbandry Structure Of Inner Mongolia; Journal of Inner Mongolia Normal University (Philosophy & Social Science) 2005-06

Du Xiaojuan ; Cheng Ji-min; Analysis of Formation Causes of Grassland Degradation in Damxung County of Tibet and Its Exploitation and Utilization; Journal of Anhui Agricultural Sciences , 2007

[4] Emily T. Yeh, Greening western China: A critical view; Geoforum 40 (2009) 884–894

[5] Jarmila Ptackova, The Great Opening of the West development strategy and its impact on the life and livelihood of Tibetan pastoralists: Sedentarisation of Tibetan pastoralists in Zeku County as a result of implementation of socioeconomic and environmental development projects in Qinghai Province, P.R. China: PhD thesis, Humboldt University, Berlin, 2013

[6] Maria E. Fernandez-Gimenez … [et al.].,Restoring community connections to the land : building resilience through community-based rangeland management in China and Mongolia, CAB International, 2012

[7] http://www.rfa.org/english/news/tibet/resist-11072014165412.html

[8] Geoffrey Wandesforde-Smith, Kristen Denninger Snyder & Lynette A. Hart (2014): Biodiversity Conservation and Protected Areas in China: Science, Law, and the Obdurate Party-State, Journal of International Wildlife Law & Policy, 17:3, 85-101,

[9] DEE MACK WILLIAMS, Grassland Enclosures: Catalyst of Land Degradation in Inner Mongolia, Human Organization, Vol. 55, No. 3, 1996

[10] J. Marc Foggin and Andrew T. Smith . 1996.Rangeland Utilization and Biodiversity on the Alpine Grasslands of Qinghai Province, People’s Republic of China. in: Conserving China’s Biodiversity (II) (PETER Johan Schei, WANG Sung and XIE Yan eds.). China Environmental Science Press. Beijing. 247-258p.

[11] James Miller ed., Religion and Ecological Sustainability in China, Routledge, 2014, 371