Blog four of four on China’s labour market for displaced Tibetans

TRAINING TIBETANS FOR BULLSHIT JOBS

This is the labour market Tibetans are now expected, sometimes compelled, to enter. All aspects of this vast, highly competitive urban labour market marks Tibetans generically as uncompetitive, backward, lacking in entrepreneurialism, untrustworthy and not even fluent in the common putonghua tongue.

Adrian Zenz has alerted us to the extended reach of the state into the rangelands of Tibet, officials declaring pastoralists to be nothing more than lumpen “rural labourers” who are increasingly surplus to requirements, a supposedly “floating population” China will benevolently train them in vocations that are needed. Since Zenz published in September 2020, there have been further boasts by local governments in Tibet of the many they are retraining.

“According to the Human Resource and Social Security Department of Qinghai province “In the first quarter of 2021, the Human Resource and Social Security Department at all levels in Qinghai have tremendously promoted the labour force transfer and employment in agricultural and pastoral areas. By the end of Feb2021, more than 184.900 labour forces of farmers and herdsmen transferred employment in Qinghai and accounted 17.6% of the annual target of 1.05 million people, and an increase of 35.8% over the same period of last year. From Jan to Feb 2021, the labour force transfer and employment of farmers and herdsmen in Qinghai solidly increased.”

From the perspective of central leaders, this means Tibetans now participate, in large numbers, in the nationwide shift to urban life, achieved through a transition into the hyper-mobility that characterises today’s China of extreme competition. Urbanisation is the engine of development, modernity, progress, wealth creation and all-round civilisation, and Tibetans must participate. Tibetans can realistically expect only entry-level employment, likely to be precarious, sometimes dangerous, with no employee rights or protections if they are injured on the job.

Persuading Tibetans they must reinvent their lives, exchanging the freedoms of the open range for the discipline of factory work, is not easy. Senior cadres complain: ““Vocational Education is an important part of the mainstream education field, with the aim of directly cultivating the application-oriented and innovative skilled talents urgently demanded by the society, and it plays an important role in social economic development particularly. However, due to the long-term influence of many factors such as history and reality, the development of Vocational Education in Tibetan related areas in Qinghai started late and has laid only on a poor foundation. There are still some problems, such as insufficiency conditions in running schools and number of professional teachers, and further strengthen counterpart support to solve the common shortage of full-time teachers and “double qualified” teachers in Vocational Schools in Qinghai Province”.

To overcome the non-competitive mentality of rural Tibetans, the party-state’s strategy is to mobilise waves of cadres to go deep into pastoral country, to exhort nomads and farmers to emigrate. Officially this is “rural revitalisation”.

“Qinghai province officially launched “sending tens of thousands of party cadres to grassroots in 2021” and actively “consolidating and expanding the work of poverty alleviation and comprehensively promoting the implementation of rural revitalization from March 1st to April 10 2021”.

“More than 13,000 party cadres based in village were despatched to enter into the households and deliver the spirit of No1 document of Central Party Committee [on rural policy] , and publicize the agricultural and rural reform, development policies in Qinghai in the period of “14th Five Year Plan”, especially the policies and measures closely related to the vital interests of farmers and herdsmen, such as consolidating and expanding the work of poverty alleviation, comprehensively promote rural revitalization, and accelerate the modernization of agricultural and rural reform in Qinghai”.

Although this mobilisation campaign is seldom noticed outside Tibet, its pace is accelerating, as planned. Yet the actual numbers shouldn’t be taken too literally, coming from cadres out for promotion, keen to claim they have fulfilled all targets, and then some. “Vocational training” includes everything from a quick class in how to fold restaurant napkins to serious and much needed training of nurses. The quickie courses predominate.

FROM LYING FLAT TO REDISCOVERING THE WAY

What makes China unique is its hyper-mobilisation, an endless rolling round in the restless search for opportunity, fulfilling the promise the system makes all the time, finally nailing it. The ongoing relocation of Tibetan nomads is one aspect of a wider hyper-mobilisation based on the assumption that labour must move to where the other factors of production congregate in enclaves and clusters. While there are many governments that relocate people deemed to be in the way of a dam, or a mine, China shoves and shunts people around landscapes for myriad reasons, and urges everyone to accept being monetised, as a mobile factor of production, as natural and inevitable.

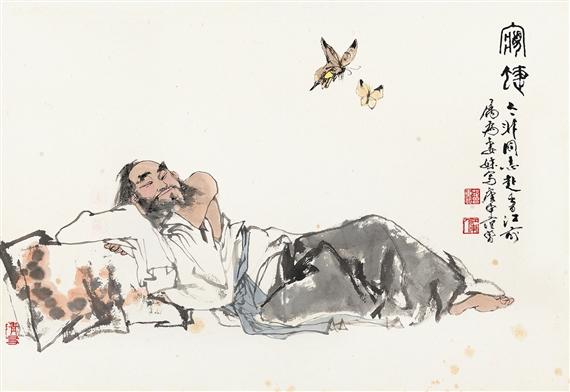

So far, the party-state treats those who opt to lie flat or go Buddhist as harmless fads among educated youth in need of time out. In a country addicted to fads and buzzwords, there is even media competition to report this latest fad. But what if it spreads? What if the fast-food delivery workers decide, in numbers, that on reflection a life of following the Taoist Way, of lying flat and going Buddhist, is what life is for, rather then pointless and endless competition? What if they redefine themselves, no longer as losers, choosing instead to embrace the Tao or the Buddha as deeply Chinese ways of being that are authentic? What if they discover Buddhism is not at all about passivity and fatalism?

Already some in the party-state are alert to this danger. Dong Zhenhua, Deputy Director, Professor and PhD Supervisor of the Philosophy Teaching and Research Department of the Party School of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China warns: “This kind of entertainment pop phenomenon is not very beneficial to the development of our business. On the one hand, this kind of entertainment will make us gradually lose the ability to think independently and be unable to judge with reason. It makes us only passively accept the information transmitted to us from the outside world, and will lose our ability to innovate and autonomy over time. On the other hand, this kind of entertainment does not have the function of educating the masses, it can only make everyone feel interesting for a while, but it has little effect on the inheritance of our excellent civilization and the spread of positive energy.”

A Baike Baidu (Wikipedia) article locates the origin of this going Buddhist meme as originating in Japan in 2014, then picked up in China. That might be OK in wealthy Japan, Baike Baidu argues, but China has a ways to go before getting as rich as Japan, so everyone must work, and not slack off: “If a society of low desires for young people is really ushered in, the future may not be bright. The negative effect of the low-desire society on the economy is very obvious. The most obvious is the weak consumption power. When Japan entered a low-desire society, it already had a relatively affluent life. China obviously has not reached this level. Once the economy stagnates, it means a higher unemployment rate, more social contradictions and less resources”.

As usual, it all comes down to money, and wealth accumulation, as a task no-one can shirk. The monetisation of all relationships, including the most intimate, accelerates ever further and faster.

“LAZY” TIBETANS AND HAN “SLACKERS”

This has the makings of tragedy. In Tibet, the party state is hustling rural folk to become urban hustlers, on the move, always on the lookout for opportunity, for the next big chance for getting rich. Yet Tibetan culture has inner strengths, abilities to work constructively with whatever arises, to discover endless consumption at best results in ephemeral satisfaction. These home truths, familiar to most Tibetans are starting to fade at just the time a new generation of young Han, often well-educated but tired of endless competition, are reaching for a more meaningful life, such as the Tibetan capability for turning poisons into wisdoms.

China’s party-state defines consumption as the driver of China’s growth in this new era of “high-quality development”, a CCP favourite phrase, so no-one can drop out. Making China a consumption-based economy is a mission all must contribute to, though slackers can be tolerated if there aren’t too many of them.

Tibetans, even in remote pastures, are increasingly drawn into this hyper mobilisation and monetisation of all human relations, sucked into a networked, ratings obsessed society where Tibetans will always be outsiders at a discount.

The lie flat young “Buddhists” show us a groundswell of an emergent China much more tolerant and open minded, better able to see and accept Tibetans as they are, even find Tibetan life commitments useful. Tibetan Buddhists tell us it is only through looking life squarely in the face, that we find liberation. We are reminded that this world we try so desperately to secure, doesn’t ultimately lend itself to trustworthiness, and that, our relentless attempt to secure it, defines “samsara.” There is another way of being in life that is empowered and courageous. However, this approach, ironically, relies upon our ability to accept the frailty and poignancy of being human.

Tibet is not lost. The drogpa ghost riders in the sky are firmly grounded, and China increasingly recognises many -not all- do have a place on the land, alongside the wildlife and national parks.

Can Tibetan livestock producers, now depicted even in propaganda as part of nature and national parks, round up the urban slackers, and show them how to live? Can something new emerge in time for overworked hyped up Han to discover Tibetans have much to offer? Or will the cadres hustle Tibetans off their rangelands and into city hypermobility first?

Exiled Tibetans understandably seldom look closely at China. The more China looms wherever you do look, the greater the natural aversion to all the endless stories of triumph. China’s discourse power grows, while Tibetans would rather get on with their own lives.

Tibetans who do look more closely at China are usually preoccupied with legal and historic questions of sovereignty and identity. Or they focus on geostrategic and security issues, border tensions.

Monitoring social change within China is not on the radar; China is far too big, the voice of the party-state too loud, it is more straightforward to assume a command-and-control model is in place, where the centre decrees and all salute.

Yet China is not uniform, nor are the masses worker ants. China is at an unusual moment, full of contradictions and new possibilities. What appears from a distance to be monolithic state capitalism, a developmentalist state bent on allocating resources to achieve its dirigiste goals, is, on the ground, an intensely competitive system with few winners. The strains of having to compete, urged on by influencers, under impossible conditions, are so great there is now a grassroots swell of opting out to lead a more authentic life, and take the consequences. This swelling birth of a counterculture is fast attracting young people tired of pointless rote learning, of teaching to the test, of endless competition for scarce rewards.