HOW TIBETANS AND BEIJING INTELLECTUALS TEAMED TO PROTECT A WILD RIVER

#5 in a series of 8 blogs on China’s latest plans for Tibetan rivers

The Gyalmo Ngulchu/Nu is the one wild mountain river of hinterland China where damming was halted by an NGO campaign that skilfully mobilised scientists, local communities, minority nationality communities further upriver, and key Beijing intellectuals able to speak privately with central leaders.

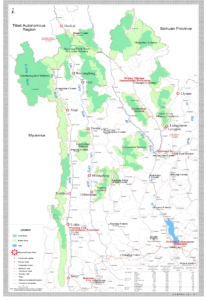

In 2016 it is 12 years since that successful campaign. Today China’s official hydropower dam plans for the Nu/Salween list no less than 26 dams, before the river exits to Myanmar, having traversed both Tibet Autonomous Region and Yunnan.[1] Only three years ago Chinese environmentalists, writing in 2013, little more than a year after Xi Jinping took power, optimistically listed no less than eight of the 26 dam sites as “cancelled”, with only two already completed, and the remaining 16 somewhere in the planning process.[2]

But in 2016, can we still be so optimistic? According to National Geographic’s recent story, local environmentalists on the Nu remain hopeful. Do they have a choice? In today’s increasingly authoritarian China, to directly disagree with official policy can be a criminal offence. So, what is current official policy?

Although the Gyalmo Ngulchu/Nu/Salween is not as well-known as the Mekong or Yangtze, it is 2800 kms long, and supports a human population of 10 million within its watershed. It begins much farther west than the Mekong or Yellow Rivers, at ~32°N, 91°30’E, in high plateau pastoral districts of Nagchu prefecture due north of Lhasa. The river’s brief moment of fame came in 2004, when Premier Wen Jiabao agreed to a halt on further damming, the culmination of a long and skilful mobilisation of social forces, including Beijing insiders and remote ethnic communities in their steep valley lands. Because of the singular success of this campaign, the story of how this coalition of insiders and outsiders, the privileged and the disempowered, actually halted the damming, has been told by many who were involved. These are stories of unlikely and uncommon alliances, and newly forged personal friendships, of urban Han Chinese learning to see through the eyes of minority nationalities, of scientists and illiterate farmers finding common cause, to protect the Nu and the nearby Dri Chu/Jinsha/Yangtze.[3]

“After the first group of journalists who travelled to Nujiang began reporting on the beauty of the area, which is notably a World Heritage Site, other journalists flocked to the basin. Within weeks hundreds of news stories and broadcasts across China were condemning the planned dams and the lack of transparency in their planning –they had not undergone the required environmental impact assessment (EIA). Environmental NGOs created a network organisation called China Rivers Network to coordinate their joint work, setting up photo exhibitions around the country to highlight the beauty of this endangered river to the public and send petitions to central leaders.”[4]

The social movement to protect the Nu River and its close neighbour the Dri Chu/Jinsha/upper Yangtze from damming even had its martyr, a young activist who died of exhaustion. This in turn became a key metaphor for famous public intellectuals such as Wang Hui.[5] His essay is a tribute to the “Son of the Jinsha River”,  who died young, exhausting himself in his round the clock campaigning to mobilise communities against the construction of a hydro dam.

who died young, exhausting himself in his round the clock campaigning to mobilise communities against the construction of a hydro dam.

Wang Hui, then editor of the liberal Dushu journal, had published a 2001 ethnographic piece by Xiao, and they had met. Wang published more by the energetic young anthropologist, but, he says, never found time to take a look at a novel Xiao wrote. As the campaign against the dam gathered strength, a Tibetan scholar Ma Jianzhong, recruited Xiao to join, and they organised a symposium in the prefectural capital of the Tibetan portion of Yunnan province, Zhongdian, later renamed Shangri-La (Xiang-er-li-la) to attract tourists. The symposium, an attempt at framing the hydro debate on Tibetan terms, was called “Tibetan Cultural and Ecological Diversity.”

Xiang recruited Wang Hui, the famous editor into his world, persuading him to stay, in Zhongdian, in Xiao’s family home, during the symposium. There Wang Hui discovered the modern Tibetan academy, authors of encyclopaedic Tibetan histories, erudite Tibetan monks who had come from Qinghai, and, from Beijing offices near by Wang Hui, “Mr Zhambei Gyaltsho, a colleague of mine from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences who was in the Institute of Ethnic Literature. I was part of the Institute of Literature, and purely due to this separation, we had never met.”

In this multicultural region of Yunnan, with Han Chinese the newcomers, the Tibetans of the upriver uplands made a strong, inclusive case for “ecological and cultural diversity as being very closely linked, and that any attempts to differentiate groups within a community based upon ethnicity and religion would rapidly erode its cultural multiplicity and any other of its organic relations, producing new inequalities. Xiao Liangzhong’s interest in his hometown did not arise from his interest in a particular ethnic or cultural group, but rather in the social networks woven together through history and their multiplicity.”

Wang was able to appreciate that the Tibetans were not chauvinists, they skilfully included everyone, and he got further involved. Seeing this Tibetan move to include all, Wang Hui became engaged in the drafting of a proposal calling for the dam project to be halted.

The essay opens with Wang Hui arriving in a remote village to pay his respects to the young man’s grave, on Tomb-Sweeping Day, a scene he evokes in detail. Xiao’s death galvanised the villagers, who “believed he died to protect his homeland, and his death motivated them to protect it, too. Some of the villagers thought of him as a river spirit who could bless and protect their home. The death of Xiao Liangzhong caused an upsurge in local sentiment against the dam project.”[6]

When the community put up the memorial declaring Xiao “The Son of Jinsha River”, an old farmer said: “Rivers on the earth are like veins in the human body. If you were to block off your own veins, you would die. The earth is the same.”

An old woman said of the young man who died that he “was just 32 years old when he left us. I’m more than 60 –I’ve lived long enough. If I could exchange my body of flesh and blood for the long-term peace and stability of this land, so that the Tiger Leaping Gorge Dam wouldn’t be built, I would be willing today to have my body smashed to pieces and my bones ground to powder.” This old woman succinctly summarised a transformative Tibetan meditation practice, of imagining one’s death, the way she describes it, as a way of overcoming all fear, and attachment to existence.[7]

It was this mobilisation that succeeded in pressuring the Yunnan provincial government to cancel the dam, as long as the protesters dispersed quickly, which they did. This account, more detailed than Wang Hui’s, makes it clear that the climax, well after Wang’s Tomb-Sweeping Day homage to his young friend, was achieved by 10,000 angry villagers surrounding government buildings, demanding justice, holding officials hostage, and refusing to disperse despite the threat of the ruthless armed police quelling them. Only when it was clear that both the Tibetan prefectural officials and the Yunnan provincial officials accepted their demands did they save everyone’s face by going home.

The skill of the Bai and Tibetan intellectuals in the Confucian arts of recruiting Wang Hui as protector and patron did much to give the social movement momentum, but it was won by mass protest, the courage of people who have been lied to too often. That’s not quite how Wang Hui tells it, but in Liu Jianqiang’s retelling of a long personal involvement with reporting the issue. It is not often that Han Chinese learn how to see through Tibetan eyes: Liu Jianqiang is an exception.[8] The Tibetan environmentalists he understands so well are now in prison.

In 2016, it is hard to imagine such a movement becoming, still less succeeding in halting a series of dams deemed necessary to national development and energy security. In the current situation of renewed authoritarianism, such mobilisations are quelled before they gather momentum. 2004 looks like a different country, which no longer exists. The Nu/Gyalmo Ngulchu/Salween is again vulnerable.

ARE THE DAM BUILDERS MAKING A COMEBACK?

Due to this decade long moratorium on damming the Nu, it remains a largely wild river, especially in its long reach across Tibet. It starts far to the west, crossed by the main highway and railway coming south, over the Tanglha mountains en route to Lhasa. A track alongside the Nu river was for centuries the tea horse road, where Tibetan took their sturdy mountain horses downriver, to trade with Yunnan’s tea growers.[9] Above, on the high plateau of Tibet, the Nu/Gyalmo Ngulchu cuts through pastoral country for over 1000 kms. There are only two dams very high up the basin, modest by today’s standards, built in the 1990s to provide electricity to small Tibetan towns in Driru county, and to electrify mining which in recent years has caused great grief among the Driru Tibetans.[10]

Between these two small dams and the entry far down river of the Nu into Yunnan and then Myanmar, there are many designated sites for hydro dams, named (going downriver) in China’s planning documents, as Reyu, Luohe, Xinrong, Tongka, Kaxi, Nujiang Qiao, Yeba, Lalong, Luola, Angqu and Emi dams, 12 altogether. Some of these are planned to be massive dams, most are at least 500 MW in electricity generating capacity. Angqu is to be 1500MW. Now that China’s environmental NGOs have again been silenced, likewise the Tibetans, who were never allowed to create their own environmental NGOs, will these dams athwart the Gyalmo Ngulchu/Nu/Salween yet be built?

WORLD’S TALLEST DAM

Even the most enthusiastic of central planners propose a 15-year timeframe, to 2030, for construction of the full hydro dam cascade on all Tibetan rivers. So it may not be clear for some time how many of these dams will be built. But a little downstream from the 12 listed above is a truly massive dam, where construction was well under way by 2014.[11] Rock mechanics scientists describe this dam, in the south easternmost corner of Tibet Autonomous Region, just before the Nu enters Yunnan: “A concrete double-curved arch dam with a maximum height of 318 m is planned, which will be one of the highest arch dams in the world. The elevation of the normal storage water level will be 1925 m and the total storage capacity will be 4.55 billion m3. The station will have a hydroelectric generating capacity of 3600 MW.”[12]

This is the Songta dam, (~28°10’N, 98° 30’E) not only “one of the highest”, but actually the tallest dam in the world if completed as planned.[13] Remarkably, it has attracted very little attention. As design and construction difficulties mounted, in this remote narrow gorge, the installed electricity generating capacity of this dam has been steadily reduced, but 3600 MW (3.6GW) remains a massive output, if achieved and actually utilised.[14] Songta provides a yardstick to gauge whether the other dams further up the Gyalmo Ngulchu/Nu will be built. If Songta is built, all 12 dams further upstream are also possible.

To Tibetans this is “the aptly named Tsawarong, where sweet cactus fruit grow and the temperature can exceed 108 degrees.”[15] Trekking this surprising corner of Tibet, Gyurme Dorje notes that some of the most famous teachers and exponents of direct experiential understanding of the nature of reality were from here. It was here that Tibetans who had entered the inconceivable, the unlanguagable, nonetheless found ways of transmitting their insight into the nature of reality, that is beyond all words and concepts. One might argue that this constitutes world heritage.

Beyond old Tsawarong, at the extreme edge of Tibet Autonomous Region’s border with Yunnan province, rises Khawa Karpo, the mountain the separates the Gyalmo Ngulchu/Nu from the nearby valley of the Dza chu/Lancang/Mekong, and the capital of the Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture of Diqing, Yunnan’s designated Tibetan region. The city of Dechen (meaning in Tibetan the great bliss that comes of realising the nature of reality) is now officially renamed Shangri-La. The rebranding sparked a tourism boom grounded in a 1930s Englishman’s fiction of a pre-Great War paradise of eternal life hidden in the Tibetan mountains. James Hilton’s invention of Shangri-La in his best seller Lost Horizon has been literally territorialised, made into a historic reality, to attract tourists, which it does. Dechen-cum-Shangri-La, on the Dza Chu/Lancang/Mekong is in the shadow of Khawa Karpo, with the Gyalmo Ngulchu/Nu the floor of its opposite side.

Khawa Karpo is one of the most popular pilgrimage circuits in all of Tibet.[16] On this arduous pilgrimage Tibetans purify the mind, dropping habits of a lifetime, to restart life anew .

[1] Sites 155 to 181 on the full list of planned dams in and just below Tibet, in The ‘Last Report’ on China’s Rivers, 2014 https://www.internationalrivers.org/china%E2%80%99s-last-rivers-report

[2] https://www.internationalrivers.org/files/attached-files/final_rivers_report_20140218_small.pdf

[3] Liu Jianqiang, Defending Tiger Leaping Gorge, 203-235 in Sam Geall ed., China and the Environment: The Green Revolution, Zed Books, 2013

https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/811-Fog-on-the-Nu-River

Zheng Qi, The Nu River Campaign and Changes in Governmental Agenda-Setting, The China Nonprofi t Review 2 (2010) 71-82

Brown, Philip H. and Xu, Kevin(2010) ‘Hydropower Development and Resettlement Policy on China’s

Nu River’, Journal of Contemporary China, 19: 66, 777 — 797

Darrin Magee, Powershed Politics: Yunnan Hydropower under Great Western Development, China Quarterly #185, 2006, 23-41

Lihui Chen, Contradictions in Dam Building in Yunnan, China: Cultural Impacts versus Economic Growth, China Report 2008; 44; 97

[4] Jennifer Turner, Reaching Across the Waters: International Cooperation Promoting Sustainable River Governance in China, Woodrow Wilson Center, 2006

https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/reaching-across-the-water-2006

https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/chinese-translation-reaching-across-the-water

[5] Wang Hui, Son of the Jinsha River: In Memory of Xiao Liangzhong, 173-190 in Wang Hui, The End of the Revolution: China and the Limits of Modernity, Verso, 2009

[6] Liu Jianqiang, Defending Tiger Leaping Gorge, 203-235 in Sam Geall ed., China and the Environment: The Green Revolution, Zed Books, 2013

Liu Jianqiang, The role of civil society in China’s anti-dam campaigns, in Brahmaputra: Towards unity, http://thirdpole.n.infoamazonia.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2014/02/Brahmaputra-Towards-Unity.pdf

[7] http://www.tibetanchod.com/cho/fearlessness/ http://www.rinpoche.com/teachings/chod.htm

[8] https://rowman.com/ISBN/9780739199732/Tibetan-Environmentalists-in-China-The-King-of-Dzi

[9] Michael Freeman and Selena Ahmed, Tea Horse Road: China’s ancient trade route to Tibet, River books, Bangkok, 2015, 3

[10] Senior Buddhist scholar arrested as repression escalates in restive Tibetan county, Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy, 14 July 2014

Tibetan man in fatal protest over mining operations, Free Tibet media release, 8 May 2014

Young Tibetan Mining Protester Dies in Prison After ‘Torture’, Radio Free Asia, 2014-02-06

Environmental Protests on the Tibetan Plateau, Thematic report commissioned by Free Tibet, 2015

[11] https://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/china-dam-project-slated-for-nu-river-quietly-passes-key-hurdle-8381

[12] Identification of structural domain boundaries at the Songta dam site based on nonparametric tests, Yanyan Li, Qing Wang et al., International Journal of Rock Mechanics & Mining Sciences 70 (2014) 177–184

[13] https://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/china-moves-to-dam-the-nu-ignoring-seismic-ecological-and-social-risks-7807

[14] https://www.internationalrivers.org/resources/china%E2%80%99s-domestic-dam-plans-draw-ire-at-home-and-abroad-7882

[15] Gyurme Dorje, Tibet Handbook, 4th edition, 2009, 515

[16] Katia Buffetrille, The Pilgrimage to Mount Kha ba dkar po: A Metaphor for bardo?, 197-220 in Christoph Cueppers ed., Searching for the Dharma, Finding Salvation – Buddhist Pilgrimage in Time and Space, Lumbini International Research Institute, 2014

Giovanni Da Col, The View from Somewhen: Events, Bodies and the Perspective of Fortune around Khawa Karpo, a Tibetan Sacred Mountain in Yunnan Province, Inner Asia 9 (2007): 215–235

Jan Salick, Anthony Amend et al., Tibetan sacred sites conserve old growth trees and cover in the eastern Himalayas, Biodiversity and Conservation (2007) 16:693–706