BLOG TWO OF TWO ON RISK MANAGEMENT: Tibetan style

China’s enthusiasm for controlling risks is not the Tibetan way. What is most striking about contemporary Tibetans is that they deal with risks, including the risk of the party state’s force majeure, neither with zealous fixation on control, nor the bitterness of the Uighur resistance. Tibetans, taking their cue from customary light touch, flexible risk management instead manage the intrusiveness of the party state with a close and intuitive reading of when and how to push back, and when to yield, in the interests of the long term.

Instead of matching obsession with obsession, tribal loyalty to the party-state with tribal loyalty to an exclusive minority nation, Tibetans tackle the everyday tasks of managing the risks of surveillance, grid management, compulsory slogan chanting, criminalisation of dissent, the social credit regime of algorithmically assigned punishments and rewards, with some aplomb. They know when to stage ritual displays of fealty to the party-state and its well salaried job opportunities. They also know when and where it is possible, even if only in private, among trusted intimates, it is possible to relax and be heartfelt.

There’s nothing like seeing a young Tibetan cadre hectoring a visiting high lama, based far from China, demanding aggressively that he obey all directives, not assemble crowds, in no way deviate from the official line, almost shouting in his face, a pantomime of official arrogance. Then, staged performance done, to the satisfaction of a hidden Han superior, the same cadre, as the lama leaves, grabs her baby and holds it up for the lama to touch on the head, in blessing, away from the official gaze. Two performances, moments apart, with little doubt as to which one came from the heart. That’s risk management with aplomb.

Such stories abound. Tibetans know how to make ritual displays of fealty to a hegemonic party-state that demands primary loyalty to the fiction of a unitary, sovereign nation-state that all Tibetans experience as an arrogant, racist conflation of the Zhonghua Han race with the Chinese state. They know when and where such ritual tribute must be paid, and then get on with their lives. They are not conflicted by their official identity as Zhonghua minzu citizens clashing with a secretly nursed alt-identity.

Such stories abound. Tibetans know how to make ritual displays of fealty to a hegemonic party-state that demands primary loyalty to the fiction of a unitary, sovereign nation-state that all Tibetans experience as an arrogant, racist conflation of the Zhonghua Han race with the Chinese state. They know when and where such ritual tribute must be paid, and then get on with their lives. They are not conflicted by their official identity as Zhonghua minzu citizens clashing with a secretly nursed alt-identity.

It is not only in risk management that Tibetans are flexible, accommodating whatever arises, making necessary adjustments, and carrying on. Flexibility is more generally a Tibetan stance towards contingency, the coincidence of causes and conditions arising, that thwart or facilitate. Tibetans generally flow like water, around obstacles, moving on, not troubled by the strain of maintaining an essentialised identity that is breached by the demands of the party-state. This is a legacy of the pervasiveness of Buddhism, even among the many who have no overt Buddhist training. To perform loyalty is not to betray an inner self. To perform is to perform, as circumstances require.

If circumstances are adverse, this is to be accepted, not as a personal blow but as the maturing of inscrutable past karma from past lives long lost to conscious remembrance, not worth agonising: why me? It’s not all about me. When, in 2001, the Dalai Lama was asked what is the saddest thing that happened in his life, he said: “Some occasions now when newly arrived Tibetans explain about their life stories, and tortures, and there are a lot of tears. Sometimes I also cry. But I think sadness is comparatively manageable. From a wider Buddhist perspective, the whole of existence is by nature suffering. So, suffering is some symptom of samsara. That also is quite useful. That’s why I sustain peace of mind”[1]

This situational fluidity is not only a way of individually coping with the jealous gods of the party; it is a social response too. Tibetans are good at thinking through the consequences of behaving this way or that. If they aren’t good at it, they listen to those who are.

RISK AS MASTER FRAME

China has always seen Tibet as inherently risky, even life-threatening, in ways that are almost unmanageable, in these times of risk management. The contrast between Chinese and Tibetan attitudes to risk is a lens that tells us much. Take a look at China’s Journal of Catastrophology (yes, there is such a word in Chinese English).

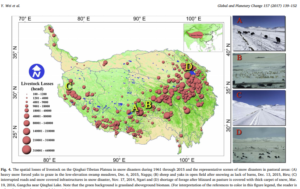

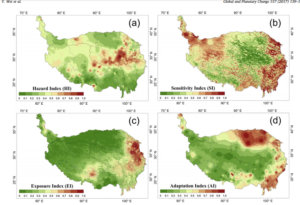

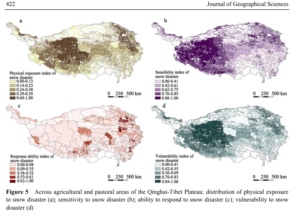

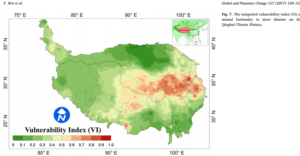

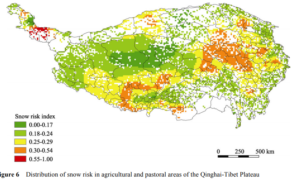

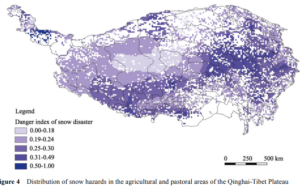

China routinely classifies Tibet as risky because of its thin air, extreme cold, proneness to earthquake and much more, and in recent years has developed many maps of the inherent riskiness of Tibet, for example, to snowstorms that are a hazard to pastoralists caught with herds that in autumn need to descend to lower altitude winter pasture but are trapped at the pass by deep snow, that even hardy yaks cannot paw through. Mapping such risks, familiar to drogpa nomads for thousands of years, does not mean risk mapping leads to risk management of risk abatement or risk compensation. It does not provide drogpa with weather risk reports, or an indexed snowstorm herd loss insurance program, of the sort successfully implemented in Mongolia, enabling herds to be quickly rebuilt after losses.

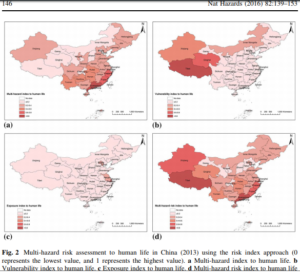

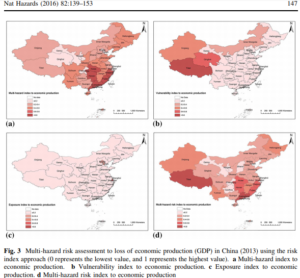

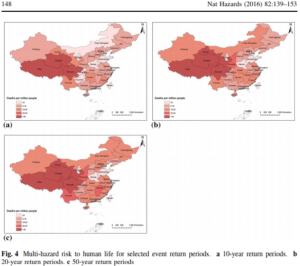

Yet China now invests heavily in risk management, making it is sign of the party-state’s mastery of nature, and capability for quick and effective response to disaster. One of the biggest restructurings of government in the 2018 rearrangement of ministries was to create a new Ministry of Emergency Management, which takes powers and staff from several other ministries to comprise a brand new agency. Official China has made it clear that its response to earthquakes, floods and other disasters is to be a measure of regime legitimacy, and party members are expected to be first on the scene when disaster strikes.[2]

Tibetans, by contrast, live with risk, as the coming together of causes and conditions that can arise at any time. This applies to natural disasters and unnatural ones such as the imposition of class warfare on the whole of Tibet, because that was consuming revolutionary China, and the never ending official fear of “splittists”, whose dislike of Han arrogance is seen as an existential threat to the whole of China. Tibetans see these bouts of persecution come in waves. They sometimes resist, and sometimes decide, for the sake of the long term, to roll with the punches.

COULD CHINA SOFTEN?

Sometimes it is all about the long game, about what it takes to survive the cruelties of this moment, in order to work gradually towards the ongoing saliency of Tibetan culture, including Buddhist insight that keeps minds supple. The eminent historian of Tibet Prof. Tsering Shakya suggests: “The Chinese state has been successful in projecting Tibetan and Uyghur people as backward populations resisting development. So there is a growing backlash in China against what might be best termed religion-based identity politics. China has successfully used this to its advantage, portraying the situation in Tibet and Xinjiang as part of the fight against the global rise of religious fundamentalism. However, there is a big difference in how the two communities are treated: Beijing is relatively soft on Tibetan Buddhists compared to Xinjiang Muslims. This is because Tibetans are not seen as the same kind of security threat as Uyghurs are and because of the growing popularity of Tibetan Buddhism.”

How did it come to pass that any Tibetan can call today’s punitive approach “relatively soft on Tibetan Buddhists”, only months after major Buddhist practice centres such as Larung Gar and Yarchen Gar were literally torn apart by bulldozers?

Tsering Shakya has a point, if one looks at the long term. For Buddhist insight into the nature of reality to survive meaningfully it must be realised, fully lived by its practitioners, at least enough of them to maintain a cohort of teachers who can transmit inner meanings to the next generation. The Tibetan Buddhists have managed to survive far greater persecution than current spasms, when for almost two decades all manifestations and organisations for Buddhist practice were violently suppressed, in the name of revolution and class war. In the hills, in mountain caves and other classic retreat places, practitioners persisted in realising in wholly embodied ways the insights of the Buddhist texts and teachers, then returned to society to exemplify them. As early as 1962, in his petition to Mao, the Tenth Panchen lama identified what was at stake: “Those who have religious knowledge will slowly die out, and religious affairs are stagnating, knowledge is not being passed on, and so we see the elimination of Buddhism, which was flourishing in Tibet and which transmitted teachings and enlightenment. This is something which I and more than ninety per cent of Tibetans cannot endure.”

The unbroken transmission of lineages of Buddhist insight, through invasion, the Great Leap, famine, the Cultural Revolution and beyond, is a remarkable achievement, barely noticed by an outside world that does not believe that transformative retraining of the mind is possible, or that continuity of transmission means more than institutional survival.

Not only has the inward path continued, unbroken, exile spread it worldwide, and the vacuity of newly wealthy China created a market for it in the biggest cities across China.[3] This strongly suggests flexible Tibetan risk management has been central to taking adversity as opportunity, a core proposition of the tantric path. The classic analogy is the peacock in the jungle, devouring poisonous plants; thriving and giving its resplendent tail a more iridescent glow.

Tsering Shakya is surely right about the growing popularity of Tibetan Buddhism, among urban Chinese finding out that wealth is not happiness. They open to the Buddhist insight that the rich man is often the most anxious, because he has more to nervously protect from risks and to make his money always grow. Whether Tibetan Buddhism appeals to young Tibetans, in exile or in Tibet, is moot, but Chinese flock to the lamas, seeking a meaningful life, beyond mere accumulation.

This is no small achievement. It could not have happened if Buddhism had been branded a foreign religion, like Islam and Christianity, quintessentially unChinese, which was the official position during the revolutionary decades.

The inculturation of Buddhism as a Chinese religion with Chinese characteristics, originally achieved 17 centuries ago, had to be renegotiated anew, with a party-state preconditioned to view all religion as poison. There is nothing inevitable, in a China that persists in insisting everything has to exhibit nebulous “Chinese characteristics”, about Buddhism regaining its standing as home-grown. This is especially true of Tibetan Buddhism, which appears superficially dissimilar to the Chan/Zen tradition, populated by different gods and demons, rituals and ritual masters nothing like the institutional Buddhism of Chinese monasteries. For decades, revolutionary China classified Buddhism as alien, Tibetan Buddhism as doubly foreign, and even today the sight of wealthy urban Chinese devotees prostrating before Tibetan lamas provokes deep unease among party officials. Hence the spasmodic outbreaks of state violence to separate teachers from students, policing the artificial distinction between laity and clerisy with walls and regulations, as if dealing with a contagion. Inevitably, the tools of risk management, of quarantining danger, are deployed.

The inculturation of Buddhism as a Chinese religion with Chinese characteristics, originally achieved 17 centuries ago, had to be renegotiated anew, with a party-state preconditioned to view all religion as poison. There is nothing inevitable, in a China that persists in insisting everything has to exhibit nebulous “Chinese characteristics”, about Buddhism regaining its standing as home-grown. This is especially true of Tibetan Buddhism, which appears superficially dissimilar to the Chan/Zen tradition, populated by different gods and demons, rituals and ritual masters nothing like the institutional Buddhism of Chinese monasteries. For decades, revolutionary China classified Buddhism as alien, Tibetan Buddhism as doubly foreign, and even today the sight of wealthy urban Chinese devotees prostrating before Tibetan lamas provokes deep unease among party officials. Hence the spasmodic outbreaks of state violence to separate teachers from students, policing the artificial distinction between laity and clerisy with walls and regulations, as if dealing with a contagion. Inevitably, the tools of risk management, of quarantining danger, are deployed.

The growing popularity of Tibetan Buddhism took great skill, patience, forbearance, fluidity and forgiveness, even an openness to the barren lives of one’s tormentors and torturers.

It took decades. It was accomplished without co-ordination or an overt strategy, as even now there is little room in the public sphere for Buddhist voices. Yet the transition occurred, a populist, nativist revival of Buddhism as a practice of mind training transcending race, class, gender and any other conventional identity. That could only be achieved by exemplary teachers leading exemplary lives, even if there were (and are) both Han and Tibetans tempted to cash in on widespread naïveté about how to choose a good teacher.

It took decades. It was accomplished without co-ordination or an overt strategy, as even now there is little room in the public sphere for Buddhist voices. Yet the transition occurred, a populist, nativist revival of Buddhism as a practice of mind training transcending race, class, gender and any other conventional identity. That could only be achieved by exemplary teachers leading exemplary lives, even if there were (and are) both Han and Tibetans tempted to cash in on widespread naïveté about how to choose a good teacher.

These are matters seldom spoken of, acknowledged or even recognised in the global diaspora of Tibetan exiles. As Tsering Shakya reminds us: “Unfortunately, much of Tibetan diaspora has become formulaic, and lacks ingenuity and creativity. Their rhetoric is confined to social media and the personality politics of a small, non-representative group of the population.” The self-appointed task of exile is to be voice of the voiceless, which requires the 97 per cent of all Tibetans, who continue to inhabit Tibet, to be voiceless victims, occasional heroic resisters, and little more.

This constricted view occludes recognition that in daily life Tibetans manage the obnoxious, racist Han Chinese presence, not just to survive the day, but to maintain Tibetan culture by focusing on long term risk management. Tibetans push back against official China’s demand for loud displays of loyalty, by manifesting behavioural compliance, and getting on with their lives. Tibetans push against Han centric racist depictions of Tibetans as backward, uncommercial, uncompetitive and unproductive, with subtlety and insistence on expanding the use of Tibetan language in public media, in public signage, in education curricula up to and including college degree courses taught in Tibetan.

Tibetans know exactly what triggers neuralgic twitch in the party-state, where the red lines are, how to push right up to the red lines, but not cross. They know full well the party-state long ago lost heart for genuine brain washing, for an inner conversion among Tibetans to seeing the world as Han see it. Official China has settled instead for a self-deluding ritual performance of “loving the party” which deludes only those who demand it. To Tibetans it is just another tax, a new wulag.

The worst part of those mandatory performances of Chineseness is that they are time consuming, but they do not threaten core identity, since Tibetans are light on core identity. All those hours of cadres earnestly explaining how kind the party is to the masses, how many benefits it has brought, all those slogans to be memorised and reproduced, all take time better spent at home with the family, or, if you are a monastic bedevilled by a “democratic management committee” of ideological enforcers, time better spent meditating.

Performative Chineseness is a punitive tax, but the result is you get to keep your state financed secure job, or to stay on in the monastery, and get on with the inner path of transformative mind training. Those may be individual benefits, but they are also prudent investments in the long term continuity of Tibetan culture and values, and in managing over the long term the corrosive aspects of alien rule.

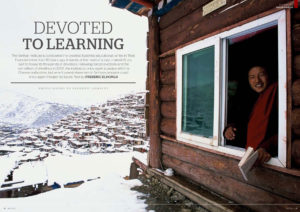

At Yarchen Gar, in 2018, only months after the bulldozers ceased demolitions of the meditation practice huts of thousands of nuns and monks, international tourists were being shown around a peaceful contemplative community at work on inner transformation, with no mention of the turmoil, no hint as to the upheavals as officials demolished, expelled, trashed, demarcated Yarchen Gar and nearby Larung Gar into separated lay and monastic zones in the name of cross-infection control.  On paper, official China had asserted itself, contriving a zone of ritual practice with no guidance from teachers, and a monastic professionals zone with no students. Having asserted state sovereignty, the bulldozers left, and oral transmission of inner realisations resumed across the walled divide between amateur and professional, lay and monastic, decreed by official intervention. Life goes on.

On paper, official China had asserted itself, contriving a zone of ritual practice with no guidance from teachers, and a monastic professionals zone with no students. Having asserted state sovereignty, the bulldozers left, and oral transmission of inner realisations resumed across the walled divide between amateur and professional, lay and monastic, decreed by official intervention. Life goes on.

Serthar Larung Gar was first destroyed by methodical official vandalism two decades ago, for the same reasons: “The growing popularity and international recognition of the institute however acted as a catalyst for very real Chinese concern. The devotion Khenpo inspires among Chinese Buddhists had been of concern to the Beijing authorities for some time. One reason was explained by a Tibetan Buddhist teacher living in the West: ‘Most of the monks studying at Serthar from China are well-educated and from urban rather than rural areas, just the sort of people that the authorities would not wish to be influenced by Tibetan Buddhism or Tibetan views.’”[4]

Not only is this Tibetan long game invisible to China’s enforcers, it remains invisible to Tibetan exiles, who have little idea what these new religious movements, popular both among Tibetans seeking a meaningful life, and among Han from all over China, signify. The daily practices of discovering the full powers of the mind remain as opaque to young exiles as to the enforcers of the party-state, all of them sharing the modernist insistence that religion is nothing more than a jumble of arbitrary dogmas. Exiled Tibetans ceased being drawn to monastic life decades ago.

Yet this rigorous mind training tradition is the source of Tibetan inner strength, resourcefulness, flexibility, ability to consider consequences and manage risks without being defined by them. Most Rukor blogs are also exercises in risk assessment. Each post tries to balance news of new risks with careful assessment of which of China’s master narratives actually mean much, on the ground.

The devotion of the Tibetans to Buddhist insight, and now the devotion of millions of Han Chinese as well, are gradually turning minds at the highest levels in China. Not only does this protect Tibet from the yanda “strike hard” disaster of Xinjiang, as Tsering Shakya says, it also means the Tibetans are slowly taming China, spasmodic outbursts of official destructiveness notwithstanding. Tibetan Buddhism is now not only normal, and acceptably Chinese, it ensures on all sides that situations do not spiral into a vortex as they have in Xinjiang. Both sides, Tibetan society and the party-state, know the limits, the tacit boundaries not to be crossed.

The khenpos of Larung Gar and Yarchen Gar are willing to stand back when China’s cycles of risk control and suspicion peak, let the destruction play itself out, and when it is spent, rebuild anew. This cycle has repeated. China is slow to learn that punitive correction of suspicious behaviour is counter-productive; or that meditation practitioners will always seek reliable spiritual guides and follow those they find, despite regulatory separations. Compared to the Cultural Revolution these statist “rectifications” are brief and useless. The connection between meditator and Vajra master is heart to heart, mind to mind direct transmission, transcending bureaucratic divisions of labour.

Tibetans worldwide should recognise, acknowledge and celebrate the strengths of Tibetans in Tibet, rather than focussing exclusively on overt and costly resistance. Unfortunately, innovative reinventers of Buddhist insight such as Larung Gar and Yarchen Gar are noticed by exiles only when persecuted. As soon as they cease being human rights headlines, they cease to be of interest.

So Tsering Shakya is surely right in saying Tibet has been spared the fate of Xinjiang, and this is an achievement of the Tibetans, who ought to be hailed for their skilfulness in crossing the great rivers of modernity with Chinese characteristics, feeling for each stone footing, one by one. It was in Tibet that China first learned the techniques of grid management, mass surveillance, disappearances, detention and torture. It was specifically Chen Quanguo, Party Secretary of Xinjiang, who spent years running Tibet Autonomous Region before transferring to Xinjiang, bringing his armamentarium of repression technologies with him.

Now, compared to the agonies of Xinjiang ripped asunder by mass incarceration and indoctrination, Tibet has been spared the worst, yet Tibetans persist, at every opportunity, in asserting the Tibetan difference, and not accept being classified as inferior Han. This, on a national scale, is risk management with aplomb.

Tibet perhaps has been spared the worst also because it is not on the road to anywhere much for China’s belt and road expansion, other than Nepal and a suspicious India. Xinjiang, however, is the heart of all of China’s Eurasian sphere of influence plans. Tibet, land of snows surrounded by mountains, has yet again been spared, because of its special topography.

While Tibet barely figures in China’s grandiose Belt & Road Initiative plans, remaining an exceptional outlier, it figures prominently in China’s new era planning for a consumption services economy, part of China’s transition from manufacturing as the path of wealth accumulation, to a demand-driven consumer society. Tibet’s place in new era China is as a destination, for Han tourists in their tens of millions, exercising their leisure consumption rights.

China markets Tibet as a wonderland. This has its hazards, not only objectification of Tibetans as exotic Other, but also the emptying of rural Tibet to pander to Han fantasies of pristine wilderness no-man’s land depopulated to superimpose Han fantasies of primal discovery. The official plan to make almost half of Tibet national park runs the risk of depopulating prime pastoral landscapes, in the name of not only tourism but also water provision for lowland China.

If that is to be the fate of Tibet, it’s still far from the agonies of Xinjiang and Tibetans may even find the transition from rural to urban life manageable. It seems the urbanisation trend these days is as much pull as push. Tibetans feel drawn to urban comforts, as do folks just about anywhere in a globalised world, and less coercion is needed.

How are Tibetans managing the risks and rewards of urbanising? Many Tibetans now say as much as 10 per cent of the two million population of Xining is now Tibetan, while only a few years back Xining, although in Tibet, was in no way Tibetan, not even a Tibetan senior school.

Tibetans now consider the consequences of city life, and the possibilities of families living both on the pasture and in the city, depending on the needs and opportunities of both. When you are young, and in need of good schooling, you live in the city, because China closed so many local schools. When you are old and in regular need of medical care, you go to the city. If you are adult, young and healthy, you stay on the land. These are the everyday risk management decisions Tibetans make, aware that despite the seductions of city life, there is also the cost of speediness, distraction, crowding, the loss of quiet and even the solitude the lamas have always exhorted us to seek, to explore the mind. The recent pop ballad hit by Lobsang Nyima reminds us Tibetans do know how to do that urban/rural risk management process, embracing the new while mindful of the value of spaciousness, upland on the high plateau.[5]

The Tibetans have survived risks and disasters, of natural and human origin, with inner strength, flexibility, enormous resilience and an eye on the long term. They will deal with rapid urbanisation with those strengths available.

[1] Pico Iyer, Over tea with the Dalai Lama, Shambhala Sun, November 2001

[2] Christian Sorace, Party Spirit Made Flesh: The Production of Legitimacy in the Aftermath of the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake, China Journal, 76, 201

[3] Gareth Fisher, From Comrades to Bodhisattvas: Moral dimensions of lay Buddhist practice in contemporary China, U Hawaii Press, 2014

[4] Destruction of Serthar Institute: A special report, Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy, 2001, 28

[5] https://highpeakspureearth.com/2018/music-video-city-by-lobsang-nyima/