WHAT’S HAPPENING TO ASIA’S MONSOONS?

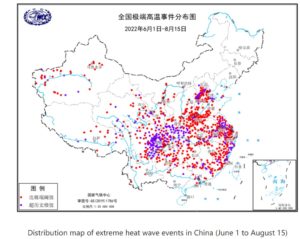

While climate change is in your face just about anywhere, nowhere is it as disastrous this summer than across China. Drought has spread right across central and southern China, due to the failure of the East Asian monsoon, usually called the Meiyu, which reliably sweeps in from the western Pacific Ocean, bringing most of the annual rainfall not only to coastal China, but far inland, as far as the merging megacities of Chongqing and Chengdu, way up the Yangtze in Sichuan.

We’ve seen the dramatic images on our newsfeed: the Yangtze a sad trickle, reservoirs so empty that stone Buddha carvings long drowned by dam building emerge again, crops failing, farmers despairing, and industries far downriver, as far as Shanghai, having to turn out the lights because the hydropower exported from Sichuan has failed.

Even further inland is Tibet, where not only the Yangtze but almost all the major rivers of Asia begin. And, beyond Tibet, to the south, is the Himalayas, and further south, India, with its own monsoon dynamic, coming in not from the Pacific but from the Indian Ocean and Bay of Bengal.

Tibetans on both sides of the Himalayas this year are having very different summers. The Indian summer southwest monsoon, despite being often unreliable, arrived and has rained heavily for months, so much so that much of Pakistan, far downriver from the Himalaya/Hindu Kush mountains is so flooded those who escape have almost nowhere to go.

How can it be so wet on one side of the Himalayas, and at the same time so dry in China’s deep inland that the many hydrodams on Tibetan rivers so lack water that the turbines have stopped turning, and far Shanghai has to turn off its lights?

What on earth is going on?

A TALE OF TWO ENTWINED MONSOONS

As the world readies for another climate COP in early November, the disjunct between wet India and dry inland China needs urgent explanation. All the more so since the Himalayas do not cut Tibet off from the South Asian monsoon, and in a normal year Tibet receives rain from both monsoons, from two great oceans.

This year, intense and prolonged heat prior to monsoon arrival, further intensified the flooding in Pakistan, which normally relies on steady glacier melt high in the Karakorum/Himalayas to maintain river flow. On top of record monsoon rains on the almost flat croplands of southern Pakistan, this monsoon season has further intensified the flooding by melting glaciers collapsing into mud slides that temporarily dam rivers, only to burst as rain intensifies further, cascading walls of muddy water down river, into already flooded villages and farmlands.[1]

In January 2022 Pakistanis were warned what would come, and seven months later, it came: “Pakistan already has more than 7,000 glaciers out of which an alarming 3,044 have become glacial lakes. Many others have been marked as a potential risk due to rising temperatures. As they melt, they can burst their banks and flood downstream. This phenomenon is called glacial lake outburst flood and results in changed periods of water flow, having a major impact on water availability for agriculture or hydropower.”

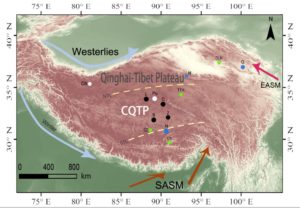

This is a tale of two monsoons, which normally arrive, persist and eventually withdraw, in an orderly, fairly predictable cycle. The Tibetan Plateau, far distant from both the Indian and Pacific Oceans, turns out to be central to this tale. How so?

Usually, the SW Monsoon of South Asia is the first to arrive, a welcome relief from the intense heat of spring, first drenching Bangladesh and the eastern Himalayas, then gradually spreading right  across India and Pakistan. Ali Tauqeer Sheikh: “The monsoons have always been part of our folklore and poetry. They are the soul of our culture, heritage and history, and are connected with our lives, lifestyles and livelihoods. Historically, we have not dreaded the monsoons, but now we have begun to fear them.”

across India and Pakistan. Ali Tauqeer Sheikh: “The monsoons have always been part of our folklore and poetry. They are the soul of our culture, heritage and history, and are connected with our lives, lifestyles and livelihoods. Historically, we have not dreaded the monsoons, but now we have begun to fear them.”

RIVERS IN THE SKY

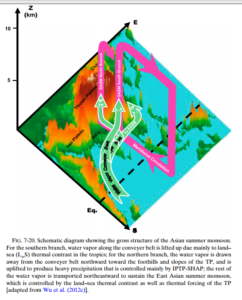

Billions of tons of water evaporated from the Indian Ocean float in, and fall, replenishing the land. What draws those clouds from the ocean inland? The intense heating of the bare rock of the mountains of Tibet in spring is a major factor, the meteorologists have been telling us for decades.

Usually when we think of Tibet we think of cold, but Lhasa is as close to the equator as Kuwait, Jordan, Cairo, New Orleans, Houston or Durban, and the intense sunshine of spring melts away the snows that reflect heat back into the sky, exposing bare rock that heats and holds heat, and draws those clouds in, calling them from afar.

Similarly, the Tibetan Plateau, which is as big as Western Europe, also plays a role in attracting the Meiyu East Asian Summer Monsoon in from the Pacific. So the meteorologists tell us.

Although Tibet is often cold due to altitude, that altitude does not quite reach into the upper atmosphere, where the Jetstream blows from west to east, bringing with it rainclouds that gather over the Mediterranean, Black and Caspian Seas outside the monsoon season. Now those westerlies blow harder than ever, no longer in opposition to China’s monsoon rains that come from the east, but now weakening consistently since 2002. China may want Tibet to look east, but the landscape increasingly looks to the west.

BLOW THE WIND WESTERLY

We are now all learning how important those jetstreams are in regulating the weather, in keeping warm and cold air separate, as long as they blow hard and unceasingly. When extreme heat hits Europe or the US, it is usually because the Jetstream has weakened, has meandered in great lethargic loops, letting hot air wander much further north than in the past. We all know what happens next: fire.

Until quite recently those jetstreams blew powerfully, far above us, and consistently. Now they meander and dally, for week after week, as a direct result of climate change, and we below have to live through the consequences. For Tibetans, wandering aimlessly with no clarity of direction, is khorwa/ samsara. The once powerful Jetstream has become a wanderer, easily distracted.

On this planet there is only one landscape so elevated and so vast that it does affect the jetstream above, and that is the Tibetan Plateau, the planetary island in the sky. Twice a year, the Jetstream switches, in order to skirt around the plateau rather than struggle to flow over it. In summer it moves sharply north. As winter starts to bite it moves south again, flowing round northern India rather than be perturbed by the bulk of the plateau.

It is this Jetstream switchback that allows the Indian monsoon in, right through the Himalayan passes, deep in to the plateau. And it is the Jetstream that also influences the East Asian Summer Monsoon. The meteorologists explain their test of “the relative roles of the continental landmass and Tibetan Plateau in configuring the seasonality. The central idea we advance is that the complex seasonality is a result of two interacting and seasonally-evolving circulations over East Asia: a moist and warm southerly monsoonal flow originating from the tropics that increases in strength as summer progresses, and an extratropical cold and dry northerly flow resulting from the influence of the Tibetan Plateau – both mechanical and thermal – on the impinging westerlies, and which weakens as summer progresses. The tropical southerlies and extratropical northerlies converge to form a dynamical humidity front that determines the location of the pre-Meiyu/Meiyu rainband, and the resulting diabatic heating in turn drives a tropical southerly flow that helps maintain the rainband. The migration of the core westerlies to the north of the Plateau during the Midsummer stage leads to the demise of the extratropical northerlies, leaving only the monsoonal flow behind.”[2]

A FAILURE FORESEEN

So how come the 2022 East Asian Summer Monsoon failed?

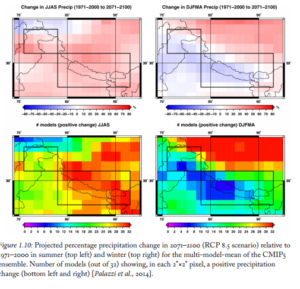

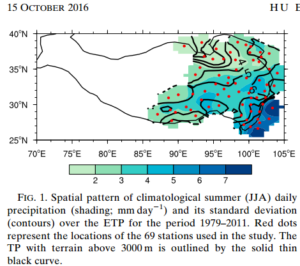

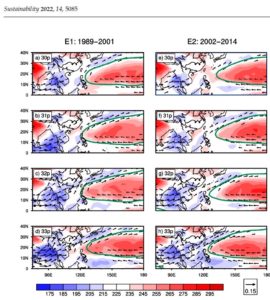

The climate change signals have been pointing to such a possibility for decades. The buildup of monsoon cloud over the West Pacific weakened dramatically, in one specific year, 2002, and has remained weak ever since, but also more unreliable, just as the climate scientists have warned us.[3]

The difference between the decades prior to 2002 and the decades since, are so marked, they can be mapped. The Pacific just ain’t so terrific as it used to be.

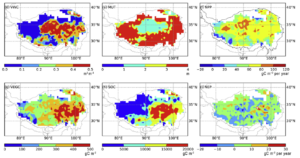

Not only do the West Pacific clouds masses weaken, and sometimes fail to reach China, so too there is a distinct drying of the wetter parts of Tibet, in Kham, and a rise in rain/snow fall further inland, in the alpine desert of northern Tibet, the Changtang, which is increasingly a land of overspilling lakes that normally have no outlet. Chinese scientists have interrogated the data accumulated from 115 weather data point generating stations in Tibet, and surrounding districts of Xinjiang, Gansu and Sichuan, over the longish span of 1963 to 2015. [4]

They conclude: “The wet southeast is trending dry while the dry center and northwest are trending wet in 1963–2015. Correspondingly, there is a drying tendency over the wet basins in the southeast [Tibet]and a wetting tendency over the dry and semi-dry basins in the center and northwest in summer, which will affect the water resources in the corresponding areas.”

Could this mean China’s massive investment in hydrodamming Tibetan rivers just below the plateau is now redundant, due to lack of summer rainfall? That is what happened in 2022. It may be a one-off. Or China may decide to redouble its dam building, especially on the Yangtze and its many Tibetan tributaries, moving further upriver, deeper into Tibetan lands.

Yet the years immediately prior to 2022 were wet in China, so wet there was much flooding, and in places far downriver on the over-exploited Yellow River, where no-one thought flooding possible. This is just what the climate scientists have been telling us: the weather is getting more unpredictable and more extreme, and the extremes are more and more extreme. New Scientist magazine says China’s drought is the most extreme event of all.

The Tibetan Plateau is also experiencing more extreme weather, with greater frequency of once in 20/50/1000 year events: “Extreme precipitation events with 20-year, 50-year, 100-year, and 200-year recurrence occurred frequently in the past decades especially in the 1980s. The greatest extreme precipitation events tend to occur after the late 1990s and in the southeastern TPS (Tibet Plateau & Surrounds).

“(1) decreased moisture transports to the southeast in summer due to the weakening of the summer monsoons and the East Asian westerly jet; (2) increased moisture transports to the center in winter due to the strengthening of the winter westerly jet and north Atlantic oscillation; and (3) decreased instability over the southeast thus suppressing precipitation and increased instability over the northwest thus promoting precipitation. All these are conducive to the drying trends in the southeast and the wetting trends in the center.”[5]

China’s extractivist approach has long treated the whole Tibetan Plateau as a free public good, to be exploited in whatever manner likely to benefit China. That includes the hydro damming of Tibetan rivers, mostly just below Tibet, in Sichuan, so intensively that Sichuan has become a major exporter of electricity, across China from west to east, all the way to the coastal factory belt. Meanwhile, energy-intensive industries such as bitcoin mining and lithium purification for EV battery manufacture, have been moving to Sichuan and Yunnan, because of the abundance of cheap hydro-electricity from all those dams. Transmitting extremely high voltage electricity across China also requires a lot of copper wire, and increasingly China’s copper comes from mines in Tibet. Enclaves of intensive extraction are now the norm across Tibet, as China marshals capital for maximum extraction.

The disastrous 2022 drought also prompted party-state officials to attack the skies, firing silver iodide at passing clouds, to demonstrate yet again the superiority of socialism with Chinese characteristics, armed with artillery firing at the heavens, in a vain attempt to force rain to fall. It didn’t work, but the media focus was on the firing, not the non-result.

Tibetans have for decades been telling all who might listen that the gods of place, of the earth and waters, are mighty upset at all the disturbances of China’s drilling, blasting, damming, tunnelling, diverting and displacing. Now, it seems, the earth gods have had enough, and have collectively pulled the plug. Endless extraction has reached its limits. The rivers, mountains, lakes, wetlands and vast pastures of Tibet are not there for the taking, common pool resources that belong to no-one, just awaiting the arrival of capital, technology and infrastructure that make Tibet a factor of production, for China’s further enrichment.

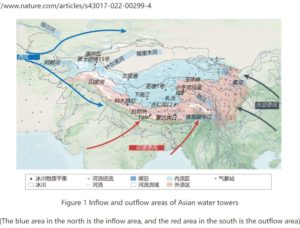

We now live in dangerously interesting times. The Tibetan Plateau is changing fast: “solid water is rapidly melting and liquid water is increasing; from a spatial point of view, the increase in liquid water is mainly in the northern inflow area, and the liquid water in some basins in the southern outflow area is decreasing trend. In this region the rapid warming of the third pole climate has changed the stock ratio of solid water such as Asian water tower glaciers and liquid water such as lakes and rivers, and the changes in atmospheric circulation in the third pole region have also changed. The strengthening of the westerly wind and the weakening of the Indian monsoon led to increased precipitation in the northern inflow area and decreased precipitation in the southern outflow area. This achievement further sheds light on the imbalance between water towers in Asia and the imbalance between water supply and water demand in the downstream region. At present, the water supply in the southern outflow area of the Asian Water Tower is on a decreasing trend, but the water demand in the downstream area of the southern outflow area is increasing sharply. Therefore, the contradiction between water supply and demand will become increasingly serious.”[6]

Can a distracted world act decisively?

When climate COP 27 opens in the Egyptian Sinai desert in early November, the Jetstream that avoids Tibet will have switched southward for winter, and the cycle begins again. The slow buildup of clouds over the oceans begins again, over both the Indian and Pacific oceans.

Are the governments of the world, assembled at the COP, capable of recognising we have taken for granted, as a free externality, the endless availability of land, water, air and skies. Now our mastery of nature threatens disaster. What will it take to face the reality that our insistence that we are the gods, and the old gods of earth and sky are long gone, is extreme foolishness? If our carbon emissions can make the jeststreams lose their energy, and now wander aimlessly, are we capable of acknowledging our limits?

Pakistan is suffering such flooding that 30m people have nowhere to go, yet Pakistan’s great friend, China, is rapidly increasing its coal burning. Pakistan rightly says it did almost nothing to cause the climate crisis, same goes for Tibet. China already burns more coal than the rest of the world put together, says it will peak emissions around the end of this decade, but in practice keeps building more and more coal burner power stations.

Until now only the Tibetan Plateau was big enough and high enough to make the Jetstream deviate, a biannual rhythm that both initiates and ends the monsoons of both India and China. Tibet matters.

Are we humans able to learn?

[1] Nibetida Guru et al., Identification Of Potential Lakes Susceptable To GLOF In Jhelum Subbasin Of Indus Basin, ISH – HYDRO 2019 INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE- OSMANIA UNIVERSITY, 2020

[2] Chiang, JCH et al., Origins of east Asian summer monsoon seasonality Journal of Climate, 2020, 33(18) https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6cp545gh ISSN 0894-8755

[3] Liangcheng Tan et al, Decreasing monsoon precipitation in southwest China during the last 240 years associated with the warming of tropical ocean, Climate Dynamics, 2017

[4] Jin Ding et al, Annual and Seasonal Precipitation and Their Extremes over the Tibetan Plateau and Its Surroundings in 1963–2015, Atmosphere, 2021, 12, 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos12050620

[5] Ding et al, Annual and Seasonal Precipitation and Their Extremes over the Tibetan Plateau, 2021, Atmosphere 12, 620. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos12050620

[6] Tandong Yao et al, The imbalance of the Asian water tower, Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2022)