Blog 1 of 2 on Tibet and the global biodiversity crisis རུ་སྐོར།

As the sober International Institute for Sustainable Development says: “An ominous existential threat hovers over humanity, increasingly so for young people and future generations. Human practices have been unsustainable for too long, overshooting planetary limits, and endangering future prosperity and wellbeing both for people and for the breathtaking diversity of all living species on the planet. Degraded ecosystems are much more than a matter of aesthetics or of moral responsibility in terms of biodiversity stewardship. Ecosystem services provided by nature are crucial for long-term survival of humans and other species of fauna and flora, and indisputable scientific evidence agrees that the path we are on leads to self-destruction.”

ON THE ROAD AGAIN

Despite pandemics and wars, the world rallied to ensure the climate heating crisis was on everybody’s mind when it most mattered, in Glasgow in late 2021, as the world’s governments assembled to take agreed collective action to prevent uncontrollable heating. Formally, that was COP 26 of UNFCC, the 26th annual gathering of all governments to strengthen the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. In UN bureaucratese a COP is Conference of Parties, meaning signatories to treaties. COP26 saw such deep mobilisation of popular hopes and fears, you only have to say COP26 and people know what it was.

Now it’s the turn of the UN Convention on Biodiversity (CBD), which at last is going to have its next COP in Montreal, starting 5 December 2022, after years of pandemic delay. COP15 of the CBD is every bit as big a deal as was Glasgow, and China is running it.

The build-up to Glasgow saw a rising crescendo of voices demanding the politicians take effective action, and the outcome, if not ideal, suggests those voices were heard.

The build-up to COP15 in Montreal is much more muted, only months before it happens. Is this because people no longer care about what happens to the sentient beings and plants we share this planet with? Of course not. It’s all about timing. Mobilising communities, scientists, media, think tanks, policy makers to all raise their voices, building momentum, takes a lot of energy.

The wildlife protection movement in recent years has peaked several times, only to have the date of COP 15 vanish, because of the pandemic. For years this COP was to be held in China, in Kunming, far inland, a further barrier to mobilisation, since China does not tolerate dissent.

FOR KUNMING READ MONTREAL THROUGHOUT

If, as originally scheduled, COP 15 had been held in 2020, that was already a date way overdue. That’s because the Convention on Biodiversity holds a major goal setting target only once every 10 years, and the last targets set in 2010 are now widely recognised as unambitious, inadequate and unrealised, in fact largely a failure. Hence the urgent need to upgrade ambition and seriousness if we humans are to avoid casually eliminating most of the wildlife of the planet. Endless scientific assessments and reports and online docos spelled out the dangers of a species -us- that has long struggled to conquer nature and is now so efficient at mastering nature we could wipe it out.

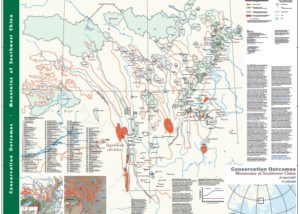

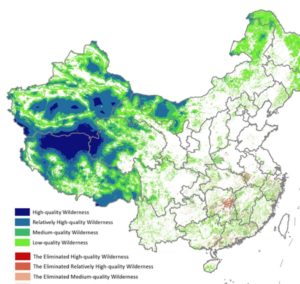

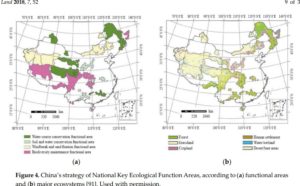

After the 2010 goals were set at a COP in Japan, by 2020 it was China’s turn. China was all set to boast it had fulfilled the 2010 goal of setting aside at least 17 per cent of its territory as biodiversity protection landscapes, chiefly by drawing red lines round prime pastures in Tibet and removing the pastoralists. China presents itself as a world leader, an exemplary model for developing countries worldwide, with new national parks that make Tibetan landscapes Chinese front and centre.

After repeated postponements, by mid-2022 China, wrestling with yet another pandemic outbreak, had had enough, and cancelled, handing over to Montreal as venue, while hanging on to its chairmanship.

No-one has noticed. No mobilisation is stirring. No torrent of scientific reports rolls in. No top influencers are posting, no new docos are launched. All is quiet on the wildlife front.

It gets worse. A COP of any global treaty is when the political leaders of the world meet. Before that, there are meetings of senior officials to thrash out a common language, an agreed program of action the politicians can then take credit for. The major preCOP meeting was in Nairobi in June 2022, and it was a disaster. Endless wrangling about finer points resulted in nothing like a coherent plan of action which all governments can sign on to. The hope was that the 17% of national territory set aside for nature would rise to 30% of each nation’s lands. Not surprisingly, many of the poorer countries, striving for development, see that as a constraint on their growth prospects, and demand compensation from the rich, who have long boasted of their manufactured landscapes. Equally unsurprising in today’s fragmenting world, the richer countries show little enthusiasm for compensating the emerging economies for foregoing development.

TIBET IS AT THE CENTRE

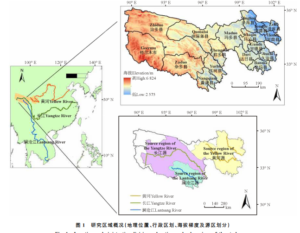

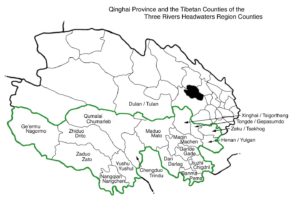

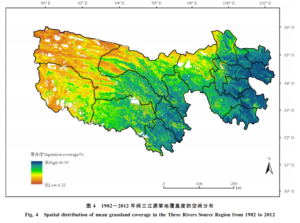

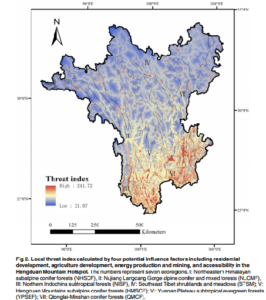

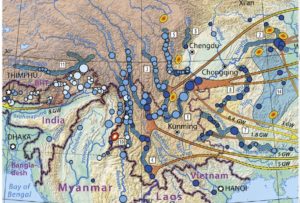

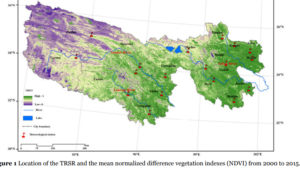

In the heart of Eurasia is Tibet. As usual, Tibet is the answer to China’s problems. In the name of biodiversity compensation and provisioning of water to lowland China, Beijing has redlined an area the size of Germany, badging it the Sanjiangyuan, the three-river source area, expelling nomads.

The Sanjiangyuan National Park swallows two entire prefectures -Yushu and Golog- that nominally are autonomous, with special status for Tibetans, since it is their home. In reality this vast landscape of rolling pastures and snow peaks is among the most productive in Tibet, and the nomads of Tibet have long known how to be both productive and sustainable, always moving on their herds well before overgrazing endangers the grasses.

But China is embarrassed that a global superpower still has, in its deep hinterland, folks who wander, reliant on nature and in tune with the cycles of nature, always willing to move on. In the eyes of China’s civilising mission, people who herd animals are little better than animals. Civilisation by definition begins with penning the livestock, cutting the grasses and forage, and taking it to the animals.

For displaced nomads the outcome is widespread poverty and dependence on state ration handouts , and emptied lands on which Tibetan rangers enforce the exclusions.

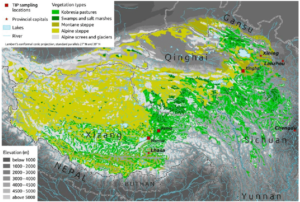

It is no accident that so much of China’s national park system is in Tibet, in areas crucial to China’s water security, hence the name of the official policy of more than 20 years, tuimu huancao, close pastures to grow more grass. In keeping with persistent misunderstanding of how pastoralism works, the herders are blamed for land degradation actually caused by bureaucratic curbs on mobility and extensive land use; and blamed for soil degradation that results from rodents endemic to the grasslands, which aerate the soil by digging, and in a good season their population explodes because they breed like rodents. In official eyes the ignorant, careless herders are to blame, and China’s top-down state control is the solution.

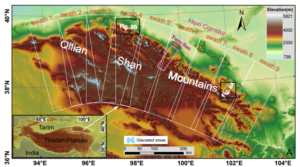

This imperial logic applies not only to the Three Rivers source that includes the upper 1000 kms of the Yellow, Yangtse and Mekong rivers, but also to other national parks in Tibet. This includes the Panda National Park on the bamboo forests of the mountains of eastern Tibet, the Chang tang of the alpine desert of northern Tibet, and the Qilian National Park (Dola Ri in Tibetan) on the northern ranges bordering Amdo and Gansu. In all of these “protected “areas, the nomads are ordered out, the opposite of the UN CBD hopes that humanity and nature can live together.

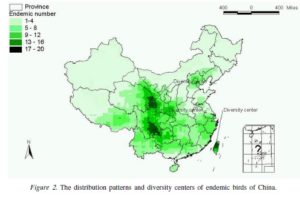

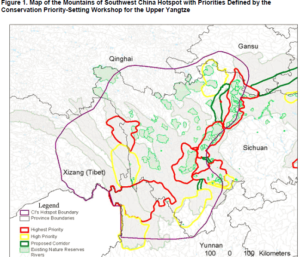

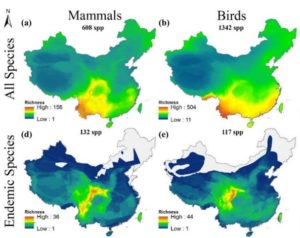

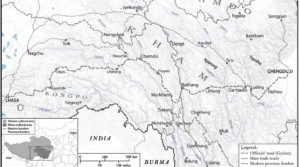

So big is the biodiversity “hotspot” of Kham it extends across the officially Tibetan prefectures of Sichuan, Qinghai, Tibet Autonomous Region and Yunnan. Only the Qinghai portion is ‘protected’, as part of the Sanjiangyuan. Designating Kham as national park, under national control, would bring together fragmented lands into a single Tibetan entity, not at all what China’s frontier construction theory seeks. So the extraordinary biodiversity of plants and animals of Kham remains unprotected.

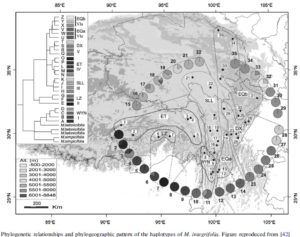

TAKING REFUGE IN TIBET

This is of global significance, far beyond Kham and the plateau. The location of Tibet at the heart of Eurasia, over the very long history of life on earth, is indeed central. There have been times in the prehistoric distant past when climates were very different to what they are now. Tens of millions of years ago the planetary climate was much warmer and wetter than now, and species that adapted to cooler climates died out widely, but survived in a rising Tibet. Later, as the global climate cooled, those animals and plants that had hung on in Tibet again spread across Eurasia.[1] Scientists call the Tibetan Plateau a refuge of relict species. Given current rapid warming, it could perhaps happen again.

It did happen again, much more recently than tens of millions of years ago. Then the Tibetan Plateau was only beginning its rise into the sky. Yet even when the plateau reached its great height, and an Ice Age gripped the earth, glaciating most of Eurasia, including Tibet, the rugged slopes of Kham remained ice free, and again became a refuge. The scientists say: “vegetation on the plateau was likely almost extirpated during the Quaternary when cold and aridity generated a hostile growth environment (Kuhle, 1998), whereas the Hengduan Mountains [Chushi Gangdrug] seem to have been minimally glaciated (Shi et al., 2006), and the Hengduan Mountains area with its deep valleys will have provided numerous refugia within the altitudinal and aspect heterogeneity afforded by a spatially extensive, complex and highly dissected landscape.”[2]

“The Central Asiatic Region is characterized by high biological diversity at ecosystem, population, and species levels. It harbors over 8000 species of vascular plants (Gotor et al. 2015), about 2000 of which occur in the plains. Its mountain ecosystems serve as the place of origin for many cultivated plants and animal breeds, refugia of plants and animal breeds, and gene pools for many globally important species. These mountains have been designated by Conservation International as one of global biodiversity hotspots— the world’s most important areas of species diversity.”[3]

Conservation International -one of the biggest and oldest of global environment protection NGOs- announced its designation of the precipitous landscapes of Kham as a major biodiversity hotspot decades before China started declaring other, less biodiverse districts of Tibet as National Parks. No-one disputes Conservation International’s designation, but China has largely ignored Kham for biodiversity protection, concentrating instead on the Tibetan watersheds of the great rivers of China.

The result is paradoxical. Most of the biodiversity of the Tibetan Plateau is not protected, yet China boasts it has fulfilled the UN Convention on Biodiversity 2010 target of setting aside 17 per cent of its territory -mostly in Tibet- as protected for biodiversity conservation.

Why not protect Kham, and its unique capacity, in two quite differing periods of geologic time, to be a refuge for wildlife? One reason is that “hotspot” misleadingly suggests a small area. This is a huge hotspot, on Conservation International’s mapping it reunites Kham, overcoming its fragmentation into Chamdo Prefecture of Tibetan Autonomous Region, Yushu Prefecture of Qinghai, Dechen (Xiang-er-li-la) Prefecture of Yunnan and Ngawa (Aba) Prefecture of Sichuan.

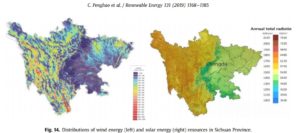

Kham is now a major exporter of electricity to lowland China, from all those hydro dams on major rivers and their upper tributaries, as well as being rich in deposits of copper, gold, silver and molybdenum. The power grids to transmit electricity right across China are in place, next step is to pump even more electricity through them, from massive wind power and solar power installations planned for Kham. Why complicate matters by locking landscapes away in national parks?

POLITICS OF REDLINING

POLITICS OF REDLINING

Fragmentation into provincial fiefdoms is what China wants. Even where China has created national parks to protect rivers, when those rivers cross provincial boundaries, the parks fail to follow. The Sanjiangyuan (Three Rivers Source) National Park embraces all of the upper 1200 kms of the Yellow River (Ma Chu in Tibetan, Huang He in Chinese), except where it leaves Qinghai, flows into great wetlands of Sichuan, and then turns back to Qinghai. The three rivers, all rising in Tibet, are the Mekong, Yangtze and Yellow, in Tibetan the Zachu, Drichu and Machu.

China’s mapping of national parks is evidently political, with scientific counting of species diversity a rationale for imposing national control over Tibetan landscapes, especially those landscapes that provide lowland China with what it cannot import: water. Making these upper riparian landscapes property of the central state makes them Chinese and no longer Tibetan, and the state then proceeds, again in the name of biodiversity conservation, to depopulate many “protected” landscapes from their traditional protectors, the Tibetan pastoralists.

Around 2008 Conservation International (CI) quietly dropped advocating for a Kham biodiversity hotspot when it saw China wasn’t going to listen. CI hoped to be heard on other issues, through its office and staff in Beijing. By now everyone but the scientists have forgotten that Kham “hotspot”, and instead encourage the parks nationalised in the name of China’s water provisioning, land degradation repair and biodiversity. Kham iss no longer mentioned, nor Hengduan Mountains, which Tibetans know as Chushi Gangdrug.

PROTECTING CHINA’S NUMBER ONE WATER TOWER

The biggest and most publicised is the Sanjiangyuan, an agglomeration of Yushu prefecture of Kham, Golog Prefecture of Amdo and several other counties, all in Qinghai province. Advance publicity celebrating the invention of Sanjiangyuan boasted of its size, and the sacred task of protecting “China’s Number One Water Tower”, a phrase that predates Sanjiangyuan by decades.

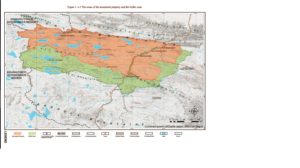

Yet here too, even in the pronouncements of central planners, Sanjiangyuan keeps changing size and shape, or disappearing altogether. The agreed global database of protected areas is Protected Planet, compiled by the georeferencers of the World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC), which is part of the UN Environment Programme. WCMC takes its data from what government supply. When Sanjiangyuan was first announced, it was close to the size of Germany. Then it shrank, as China realised those prime pastoral landscapes also have the potential to produce a lot of the meat urban China desires. Then Sanjiangyuan disappeared altogether from WCMC maps. The maps displaying here are screenshots of WCMC mapping years ago. If, in 2022, you search for Sanjiangyuan on the Protected Planet website, you get nothing.

What happened? Here it gets murky. China’s Wikipedia, the usually reliable Baike Baidu states the area designated as Sanjiangyuan bundles 16 counties, totalling 302,500 sq kms; yet the official national park is redefined as 191,000 sq kms, and its status may be nature reserve, or national park, both terms are used. This reflects the unusually slow approach adopted by the central government, which is clearly in charge, rather than provincial or prefectural governments.

Officially Sanjiangyuan National Park is in a preliminary trial stage or pilot system. Why the cautious approach in a China where campaign-style mobilisations are the norm, to get things done, fast? Is it because of the enormity of the landscapes? Is it because the half a million Tibetans living in these prime pastures know many are to be removed, since it is explicitly stated in the official plan, and they will resist? Is it because mapping the rather limited biodiversity of the redlined enclosure takes a long time? Is it because this is prime livestock raising country, and China has not only a desire for more meat but major investors, such as Shanghai Municipality, wanting to intensify livestock/feedlot/abattoir/cold chain export of meat from Golog?

All of the above are in play now, although mapping biodiversity is no longer a big task, as it has already been done, with hundreds of scientific reports published. Not only is biodiversity counted, areas of soil degradation are also well mapped, and blamed on ignorant, careless nomads, rather than decades of state failure that constricted nomadic mobility. Those areas of exposed soil are often caused by rodent population surges in favourable seasons that usefully aerate the soil by digging, a natural and beneficial cycle that has never been seen by Tibetans as problematic, but is labelled by China as degradation, requiring mass rodent poisoning, financed by the German government.

It is the local Tibetan populations who are made to poison the pikas. It is the Tibetan pastoralists who are now excluded from the scientifically designated core areas that permit no human presence at all (other than scientists). So much for the UN CBD slogans about living with nature, and nature-based solutions that include humans.

The Qinghai government website proclaims Sanjiangyuan as Qinghai’s business card. Ever since Qinghai province elevated its profile in Beijing by badging itself as “China’s Number One Water Tower”, back in the 1980s, scientists and their quadrats have busily mapped the grasslands, wetlands, the great rivers and their many Tibetan sources, and their ultimate sources up in mountainous, in glaciated permafrost.

Decades of scientific effort resulted in a threefold designation of all lands within the Sanjiangyuan red line: core, buffer and experimental. The core excludes humans, in the name of objectively proven scientific necessity. The surrounding buffer areas must restrict human activity in order to fulfil the master ideology of tuimu huancao, close pastures to grow more grass. The experimental zones are, to the scientists, indeed experimental, in the sense that they don’t know enough about who -human or animal- lives there and what their impacts and needs are.

IF EXCLUDING TIBETANS FROM THEIR LANDS IS THE SOLUTION, WHAT IS THE PROBLEM?

This triple categorisation imposes on the mobile pastoralists of Amdo a slew of regulatory restraints, exclusions and complications, none of which make sense to those who know their lands, know how to care for landscape sustainability, and find these diktats inexplicable.[5]

Nomad bewilderment at ongoing removals, displacements could, the authorities fear, turn to resistance, so must be carefully managed at a pace that is manageable. The Amdo nomads rose in revolt in 1958, and it took heavy artillery and aerial bombardment to quell them.[6] That is plenty reason for a cautious approach, since many central policy planning decrees insist removals must continue. The announced strategy is that a cohort of park rangers will be recruited from the Sanjiangyuan population of nomads, an attractive proposition for people accustomed to living off uncertainty, who value the lifelong security of a government job. The deal is that one healthy young, usually male adult from each nomad family will be recruited. That is a pilot system.

But there’s a catch. The primary responsibility of these park rangers, apart from collecting trash, is to enforce regulations, especially the policing of removals, both of people and their herds of yaks, sheep and goats, and making sure they don’t come back, or hide animals up the winding valleys, or rent the herd out to remaining neighbours. Sons may have to evict mothers.

The initial recruitments have been done, but training takes time. Transferring loyalty and identity from family and clan to a remote party-state is not achieved overnight, and China seeks a reputation, at the December 2022 Montreal CBD COP it chairs, as an enlightened, progressive, inclusive, modern and exemplary national park administrator, saviour of wildlife. It will parade its new Panda National Park, also on mostly Tibetan lands, and its Qilian [Dola Riwo in Tibetan] National Park as ideals the rest of the world can learn from and adopt. But by far the biggest is Sanjiangyuan.

NOW YOU SEE IT, NOW YOU DON’T

However, there are other reasons why Sanjiangyuan disappeared from Protected Planet WCMC maps years ago and has not reappeared.

No longer are the scientists the only Han Chinese in the Sanjiangyuan. Extractive industries, intensified meat production and above all, tourism potential are all industries attracting investment, both from the party-state central, and from local entrepreneurs.

The biggest town is Yushu [Jyegu or Jyekundo in Tibetan], an old long-haul trading caravan town now completely rebuilt with Chinese characteristics following a massive earthquake in 2010. Now a town of 125,000, the Tibetan businesses on the main street are now removed to side streets, and the centre is now full of China’s administrative offices, banks and travel agencies. Yushu municipality used to be Yushu prefecture, and a further 220,000 Tibetans remain on the municipality grasslands.

If, as planned, Yushu and other pastoral districts within the massive Sanjiangyuan, are to flourish as tourism destinations, are the remaining, colourful, horseback pastoralists a liability or an asset? Here again China is changing. The disdain of the Beijing elite and the narrow ecological frame of the scientists are giving way to a popular discovery of Tibet as the antidote to pressurised urban competitive stress. The rolling pastures of Tibet are a desirable consumable. Tibet is fast becoming a desirable destination, exotic yet Chinese, spacious and beautiful yet the hotels are luxurious, as good as travelling to another country yet wholly Chinese from street signs to infrastructure.

THE FUTURE IS CHINESE

All of these futures now compete; good reasons for Sanjiangyuan’s no-show on Protected Planet maps. Yet all these futures are Chinese, with the Tibetans as objects of the Chinese gaze, as backgrounder livestock producers, as photogenic, exotic horse riders and racers, or as biodiversity park rangers.

We have come a long way from biodiversity as the master narrative determining the Sanjiangyuan discourse, while ignoring most of Kham and the far greater biodiversity of the precipitous valley slopes at the forearc of the Tibetan Plateau’s inexorable push into China.

[1] Cindy Q. Tang et al., Identifying long-term stable refugia for relict plant species in East Asia, NATURE COMMUNICATIONS, 2018, 9:4488

Cindy Q. Tang, The Subtropical Vegetation of Southwestern China: Plant Distribution, Diversity and Ecology, Springer 2015

[2] Robert A. Spicer, Alexander Farnsworth, Tao Su, Cenozoic topography, monsoons and biodiversity conservation within the Tibetan Region: An evolving story, Plant Diversity 42 (2020) 229-254

Li J, McCarthy TM, Wang H, Weckworth BV, Schaller GB, Mishra C, Lu Z, Beissinger SR (2016) Climate refugia of snow leopards in High Asia. Biological Conservation, 203:188–196

[3] Chunlin Long. Karl Hammer. Zhijun Li, The Central Asiatic region of cultivated plants, Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution (2021) 68:1117–1133

[4] Yongjie Wu, Shane G. DuBay, Robert K. Colwell, Jianghong Ran and Fumin Lei, Mobile hotspots and refugia of avian diversity in the mountains of south-west China under past and contemporary global climate change, Journal of Biogeography, (2017) 44, 615–626

[5] Jarmila Ptackova, Exile from the Grasslands: Tibetan Herders and Chinese Development Projects, U Washington Press, 2020

[6] Jianglin Li, When the Iron Bird Flies: China’s Secret War in Tibet, Stanford University Press, 2022