Blog one of three on corona virus in Tibet, China and worldwide

In early February 2020 Rukor published an analysis of the new corona virus, both in China and Tibet, and how Tibetan and Chinese healers were responding.

That post was premature, before it was obvious the whole world would have to tread the infection path China transmitted globally.

Two months later, with a global pandemic spreading fast, and no-one able to say the worst is past, seems the right moment to revisit the virus, its origins and its impacts not only on lungs but on minds and societies, taking Wuhan as example.

To revisit virus rampant is not to dwell too much on apportioning blame. There is so much blaming at the moment, accusations, counter accusations, false information at a time when we need to work together both at community and global levels. It is important to identify how and why this virus jumped into the human realm and spread so fast. But what matters most is to relearn our common humanity, and that we all face a common threat, with no-one exempt.

So, amid the din of advice, panic and confusion, this blog focusses on just a few voices, on the ground, in virus epicentres, giving us ground zero access to the emotional journeys of fear, lockdown and acute anxiety.

We now know so much more; above all we have the voices of people inside Wuhan, and their photos of how it all began, so we can learn from their experience what it is actually like under lengthy lockdown, an invisible, unseen danger present everywhere. We have many posts by Woeser, monitoring the virus spread, made available in English by Highpeakspureearth.

In rich countries, enormous efforts are under way to prevent economic collapse as well as effective monitoring, contact tracing and treatment of those with the virus. In poorer countries, not only do they lack state capacity for coherent response, investors from rich countries are pulling out, resulting in economic crisis at the worst possible moment.

We are suddenly in a Hobbesian world of each against all, with almost zero co-operation between states. The UN is almost totally helpless and silent; its’ appeal for trillions in aid to the poorest countries hardly got a mention in media. We are in Mad Max post apocalypse end times survivalist mode, just like that. The security state has yet again expanded its surveillance of us all, especially where we are and where we go. It’s as if those whose professions thrive on fear and suspicion were ready for this moment, ready to make ambit claims for massive handouts, expanded powers and privileged status. Never let a crisis go to waste.

Those handouts and subsidies will have to be paid for by austerity for us all, not just for a few years but for probably a generation, by those already precariously hanging in to a whirling gig economy.

So there is a lot of sorting, clarifying, rectifying to do, and little prospect of a return to normal. The worst that could happen is a protracted blame game, exacerbating the tribal divides already well entrenched in most countries.

WOMEN OF WUHAN

That’s all in the future. Right now, we can learn from Wuhan, listen to Wuhan voices, share their pain, grief, strength, endurance. They were the first, now it’s our turn. If we did look at Wuhan at all, it was from a great distance, through the rhetorics of state power. Now it’s time to return to street level, to the lives of individuals, who could be us today or tomorrow.

Wuhan is to China what Chicago is to the US: a major city that works as a hub connecting everywhere to everywhere else. Wuhan, on the midYangtze, a long way downriver from Tibet, is a long way upriver from Shanghai. If you want to fly across the huge territory of China, chances are you’ll fly into Wuhan first, get reshuffled onto another flight and on to your destination.

That hub reshuttling is, we now recognise, an ideal opportunity for a highly infectious virus to spread as fast and far as possible. Wuhan was the conveyor belt, as we came to know too late. Millions left Wuhan to celebrate new year with folks back home, because no-one warned them the virus was spreading everywhere.

What does this mean, in daily life, especially if you work in a hospital in Wuhan, because you volunteered to go there to help out in a crisis:

Everyday

Haze, shady rain

Five days, damp and dismally quiet

Cold and cruel, tears and injury

These dull and murky words.

How much I hope you stay away

At the guesthouse in self-isolation

Without time, without days

No sound and no air

Writing material, psychological intervention.

Place a hundred fearful hearts in each respective palm

The trembling, the dread, the crying and despair

Throw it away with those muddied in poison.

One person’s room

Is divided into a contaminated area and a clean area.

Wash your hands, wash your hands. Mask, mask

Forced to correct all bad habits.

Right now, everyone knows that a bat is responsible for the poison

And calling the crime poisoning is sketching it lightly.

The poison from seventeen years ago is still fresh in my memory.

Today is a carbon copy of yesterday

But the poison isn’t yesterday’s poison.

People’s pampering gave rise to its cunning

Strong contagion is the fruit of their pampering.

Very late at night, what I most want to do

Is give those bats hidden in their caves

Steel armour to put on

Engraved with the two characters, “Wuhan.”

Leave all the blades with no handles

Leave all the teeth nothing to bite.

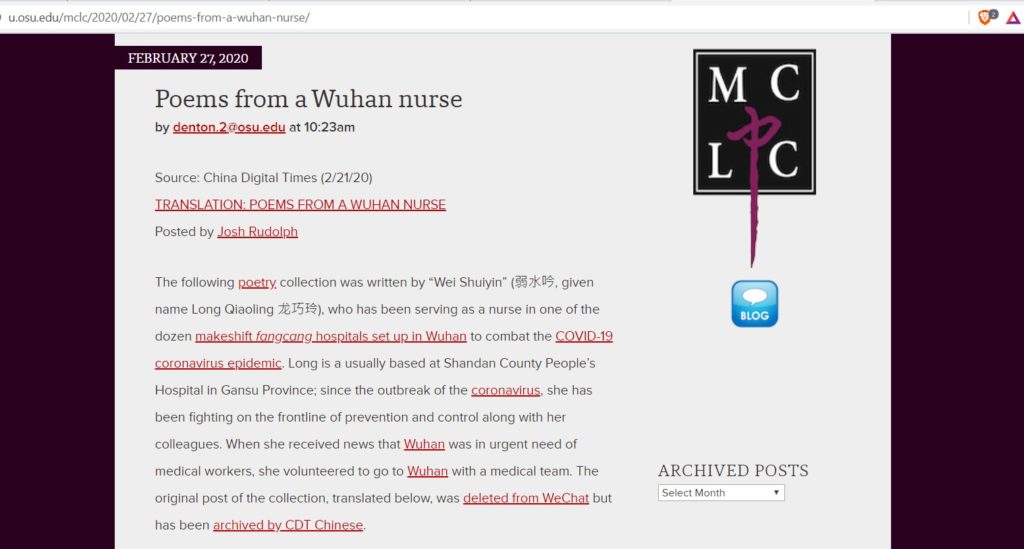

These are the words of nurse Wei Shuiyin, an accomplished poet who flew into Wuhan from Gansu to help out, on the front line. Nurses did die in Wuhan. Wei Shuiyin is the poetic penname, evoking gently flowing water, of Long Qiaoling 龙巧玲, who nurses in Shandan county hospital, immediately adjacent to Tibet Amdo.

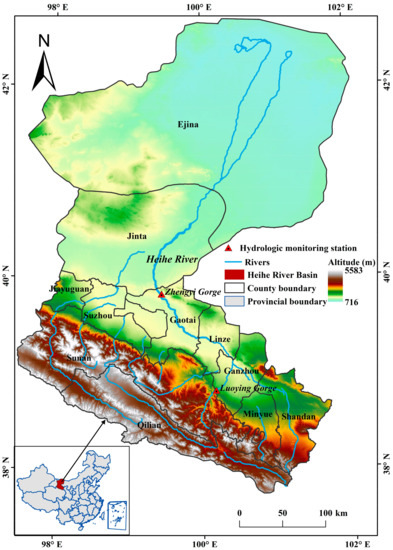

Shandan is one of the driest parts of the Hexi Corridor of Gansu, and relies for its water on the Dola Riwo (Qilian Shan) mountains of northern Amdo, and the Waden Chu river draining Tibet’s northernmost mountains eastward.

The poison of 17 years ago is SARS, which some remember and learned from, and many forgot. The pampering/spoiling/doting/人溺爱 that caused this poison to infect humans is the selfish, self-indulgent display of wealth, conspicuously consuming wildlife, cooked and eaten after procuring live animals at the Wuhan wet market. It was the proliferating Wuhan meat market that enabled this virus to jump from animals to people, exposing the entire human species to contagion to which no human is immune because until now no human immune system has ever been exposed to it. In medical jargon, we are all corona virus naïve, like newborns thrust into a world full of dangers. Now we are all naïfs.

Tibetans lost naivete long ago, after exposure not only to artillery barrages and aerial bombardment officially defined as peaceful liberation; and compulsory class warfare officially defined as democratic reform.

Tibetans have witnessed culture heroes such as Sonam Dargey (Soinam Dajie in Chinese) who risked and lost his life to protect Tibetan wild animals, then shamelessly appropriated as an official heroic worker and martyr, long after his death, to the greater glory of the party-state. The apotheosis of Wuhan doctor Li Wenliang, now an official martyr of the glorious national corona war, is a similar shameless appropriation of someone who stood up for truth and compassion and suffered for it. Sonam Dargey has been remade officially into an ancestor of China’s drive to build national parks in Tibet, while erasing from memory the mountain patrol of Tibetans in their jeeps tracking and confronting the slaughterers of Tibetan antelopes. Their collective effort is erased, while their leader is officially enshrined.

https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s?__biz=MzU4MTY2ODQ3Mg==&mid=2247518492&idx=3&sn=2b0d64a17fc7a78efa7751eea3f5f602&chksm=fd46d20bca315b1dcd0821440592f30e5403f608f86dd91ddf1bf23425c2f788d8c77b5e474a&scene=27#wechat_redirect

IN THE HEART OF LOCKDOWN

On February 8, Lantern Festival Night, far from her Hexi Corridor home, Wei Shuiyin wrote:

Night of the Lantern Festival

Outside an eighth floor window of the Wuhan Jinlaiya Hotel

Lanterns already lighting the city

The splendour of skyscraper silhouettes

Clarifying the true colours of the night

Silent. Sombre. Frigid.

I know that through the lanterns

Further and deeper in the background

Even more windows are black

Black as a cave, as a bat, as if swallowed up

Like a hidden poison with a flowery crown

In the darkness I stare into the distance

Look into the distance of the Yangtze, the Han River

The distance of the Yellow Crane Tower

The distance of the makeshift hospital

The distance of the Gansu Hexi Corridor

The distance of the Huangpu River in Shanghai

The distance of heaven using a long spoon to feed us all

The darkness still spreads

But I’ve no doubt, all is well

As the Lantern Festival moon rises

All is well, all is bright

The blackness of bats, of caves, of the dark, of danger are all around; and Wei Shuiyin is alone. Yet she remains stoic, determined to continue tending to the sick. Amid the blackness there is light.

Day after day, shift after shift, she worked, a hundred nursing sisters alongside her worked in the temporary hospital hastily erected in Wuhan. The strain was enormous. The protocol governing use of personal protective equipment (PPE) not only conceals the individuality of faces, it disallows taking off your PPE, already in short supply, even to use the toilet. Not surprisingly, fellow nurses, unable to eat, unable to take a break, almost faint from low blood sugar:

Little Sister, Tonight I’m Ashamed of the Praise

In the early hour of two o’clock

Thunder and lightning, wind and rain

The iron plates that blocked the doors have been overturned

A tiny figure was carried home by the storm

Floating like a scrap of paper

“Little sister, why did you come back early?”

“Hypoglycaemic dizziness, group leader let me go”

“Forty-minute travel time?”

“A Wuhan taxi driver took me”

Face pale, voice weak

The thermometer at her forehead reads 33.1°C

A spray of disinfectant, wash hands, repeat

Wipe clean nostrils, ears

Monitoring the operation, my hand trembled

Through my protective goggles

I can’t tell if the drops on her face

Are tears or splashed disinfectant

Remove the mask

Forehead, nose, cheek, ears

Blisters, boils–accomplices of hypoglycaemia and the cold rallying towards me

I’ve no strength to say anything

Any consolation will seem a false show of affection

Change clothing, shoes

Step back into disposable slippers

Shower in water above 56°C, don’t eat for a half hour

Everyone knows

Tightly wrap your body in protective clothing for a dozen hours

Don’t eat don’t drink don’t evacuate

Have to eat and drink less before starting work

Ah, protective clothing, how is there still a shortage?

Can you let her change to a new protective gown during the shift?

Even if work hours are extended?

The little sister who returned with hypoglycaemia

So far, I haven’t been able to remember your face

A hundred sisters

A hundred masks covering unknown beauty

Concealing how much hypoglycaemia from my sight

Perhaps, there are things I can’t say

Little sister, no praise tonight

All songs of praise are guilty

All deceived consciences

Will kneel to you

Put on a facemask, the instant you turn

I suddenly call to mind

I should add another mask

Me, facing this erupting storm

Should I play deaf and dumb

The nurses, doctors, ambulance drivers are culture heroes, keeping alive so many who otherwise would succumb. Why then does our poet headline this graphic account of what it’s like at ground zero, moment by moment “I’m ashamed of the praise.”

THE SECURITY STATE DEMANDS GRATITUDE AND PRAISE

What deeply distresses our poet is not the unending work of saving lives, or popular praise, but the entry of a distant praise singer, out to praise itself by praising the workers. The entry of the state, of the massive propaganda apparatus, praising itself as infallible and exemplary, is what causes Long Qiaoling the deepest pain. She does not want to be labelled a model worker, a shining example of sacrifice, to be appropriated by the propaganda machine even before the dying are cold:

Please Don’t Disturb

Please allow me to take off my protective clothes and mask

To remove the flesh of my body from its armour

Let me trust my own health

Let me breathe undisturbed

Ah….

The slogans are yours

The praise is yours

The propaganda, the model workers, all yours

I am merely performing my duties

Acting on a healer’s conscience

Often, there’s no choice but to go to battle bare-chested

Without time to choose between life and death

Genuinely without any lofty ideals

Please, don’t decorate me in garlands

Don’t give me applause

Spare me recognition for work injury, martyrdom, or any other merits

I didn’t come to Wuhan to admire the cherry blossoms

And I didn’t come for the scenery, the reception of flattery

I just want to return home safe when the epidemic ends

Even if all that remains are my bones

I must bring myself home to my children and parents

I ask:

Who wants to carry a comrade’s ashes

Setting foot on the road home

Media, journalists

Please don’t disturb me again

What you call the actual facts, the data

I haven’t the time or the inclination to follow

Weary all day, all night

Rest, sleep

This is more important than your praise

I invite you to go look, if you are able

At those washed out homes

Does smoke rise from the chimneys

The cell phones drifting about the crematorium

Have their owners been found?

Wei Shuiyin is weary, and uninterested in turning her raw experience into data and journalist’s clichés that only distance the reader from raw reality. In her weariness is clarity, and a focus on details that say it all. Usually we worry about losing our phone, but in the crematorium the phones pile up, having lost their owners. No-one knows what to do.

The party-state of course knows what to do, at all times since, by definition, it is the wise and capable leader of all, solver of all problems and none may disagree. The official apparat is out to bestow labels: model worker, even martyr, thereby glorifying itself. So shameless and insistent is the party-state, it demands gratitude when all anyone wants to be is take time to mourn. The self-referential self-importance of the central leaders is tone deaf to the grief.

The virus did not originate in Tibet, but compulsory “gratitude education” did, and from Tibet it spread virally to Xinjiang and now right across China.

Tibetans remember the 1980s, when CCP secretary Hu Yaobang apologised for the extremes of the Cultural Revolution and ordered Han cadres stationed in Tibet to either learn to speak Tibetan, or leave.

Neither happened, and by 1989 Hu Yaobang himself was ousted by party hardliners who accused him of sympathising too much with the patriotic protesters in Tiananmen.

For so many Tibetans the 1980s seemed promising, but the promise was never fulfilled, culminating in the 1987 uprising. Above all, the 1980s were a time of shock and trauma, of mourning the 18 unrelenting years from 1958 to 1976 when revolutionary China made war against everything Tibetan, destroying everything old.

The party never understood the need to mourn. When Dharamsala was allowed to send delegations into Tibet, to hear that grief, it overwhelmed everyone. Leader of the 1979 delegation Lobsang Samten, a younger brother of the Dalai Lama was so overcome by torrential outpourings of grief he later died of a broken heart.

Cadres accompanying the Tibetan delegation were shocked to discover that Tibetans were so traumatised. “Beijing’s ignorance of actual conditions in Tibet, cultivated by glowing reports and wildly exaggerated claims conveyed to Beijing by Chinese cadres in Tibet, led to an overly optimistic view of the ease with which it would be possible to impress the Dalai Lama and other Tibetans in exile and convince them to return. The Chinese believed much of their own propaganda about material progress, the achievements of ‘people’s democracy’ under socialism. The strictly conformist regime imposed by the Chinese themselves isolated them from accurate information concerning the real feelings of Tibetans.”[1]

Beijing was again shocked in 2020 when senior Wuhan party officials demanded Wuhan show gratitude for the party’s corona crisis response. “Anger simmered on social media in China March 7, 2020, as state media reported remarks made by Wang Zhonglin 王忠林 Wuhan’s new top official, during a video conference on the city’s response to the coronavirus epidemic. Wang reportedly said that it was necessary to “carry out gratitude education among the citizens of the whole city, so that they thank the General Secretary [Xi Jinping], thank the Chinese Communist Party, heed the Party, walk with the Party, and create strong positive energy.”

Where does the concept of “gratitude education” 感恩教育 come from? What are the syllabus and pedagogy of gratitude education? To Tibetans this is a familiar demand of the new masters, going back to the 1950s, ethnographer Emily Yeh tells us, when “in official history, the introduction of vegetable cultivation is associated not only with a blow to “imperial” arrogance but also, deploying the metaphor of Chinese nation as family, with Tibetan gratitude for the care of the elder brother Han’s assistance.”[2]

Gratitude education is a syllabus for ensuring Tibetans understand expressions of gratitude are required, on demand. Depicting the Han supermajority as the strong elder brother and Tibetans as the weaker younger brother positions Tibet lower in the Confucian hierarchy of who owes filial piety to whom. Like other Confucian precepts, mandatory gratitude is best instilled by rote learning and repetition, behavioural modifications leading to heartfelt adoption of correct attitudes. In China, behavioural psychology has a long lineage. Modern China’s gratitude education began in Tibet before spreading across China.

Beijing was shocked by popular revulsion at the 7 March command to show gratitude, but it still took a further four weeks before an official mourning ceremony was held, led by Xi Jinping. He waited until the annual tomb sweeping day for honouring the dead, the Qing Ming, making the Wuhan virus deaths part of Confucian filial piety towards ancestors.

CORONA VIRUS IN TIBET

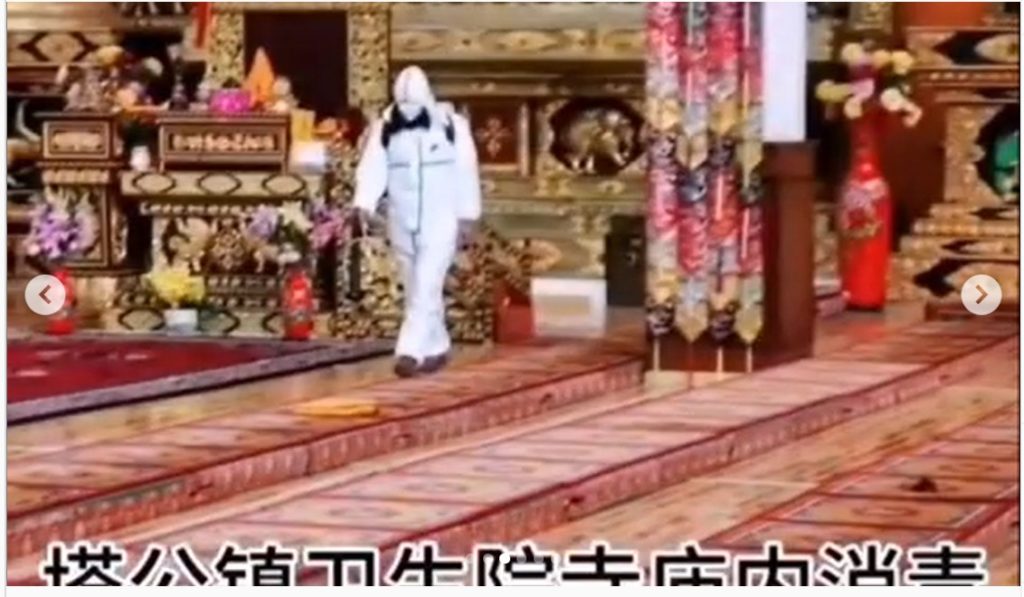

Central leaders take pride in central solutions to problems defined by central leaders. One size fits all. Seldom do policies designed for overcrowded cities work well in Tibet. But whole-of-government 举国体制 Jǔguó tǐzhì policy prescriptions apply to all. So even the remotest of Tibetan areas had to shut down, once it became clear that suppression of essential virus spread information failed to halt the virus spread.

Before everything belatedly shut, the virus spread from Wuhan, even into some of the remotest of Tibetan communities, by people coming from Wuhan.

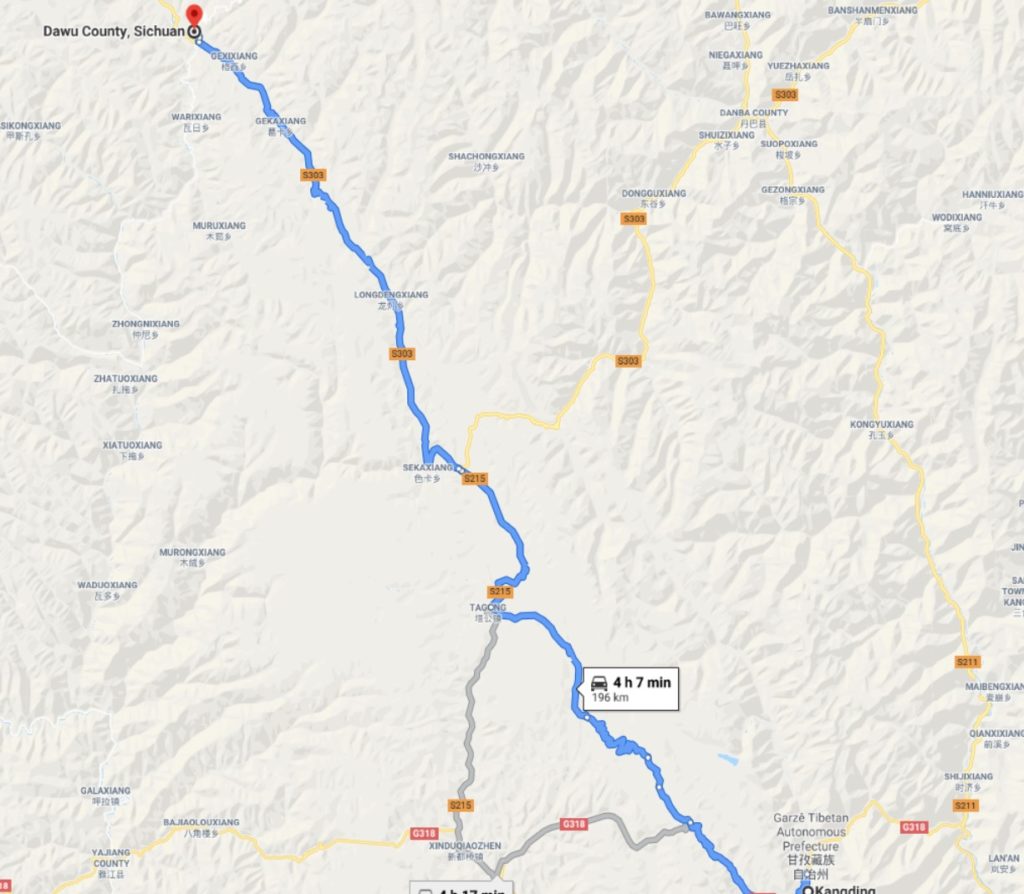

The worst we know of so far was Tawu (རྟའུ་་རྲོང་ rTa’u in Tibetan, 道孚 Daofu in Chinese), a community tucked away in the rugged landscapes of Kham. Tawu (like Rebkong) is a transition town from the more densely populated lowlands below to the pastoral highlands above. Tawu county’s average altitude is 3245m, which is quite low for Tibet, and it is on one of the few highways linking China’s two routes into Tibet from Sichuan. The S303 Highway brought corona virus to Tawu county, and its 57,000 people, overwhelmingly Tibetan but with an increasing immigrant population. The official gazetteer describes this county as well endowed, “rich in mineral resources such as gold, iron, lead, copper, hot springs and cordyceps” (caterpillar fungus) and water flow of 4.144 billion cubic meters, capable of generating hydropower of 1.538 million kilowatts. Plenty of opportunities for lowland immigrants, including from Wuhan.

Access to Tawu has sped up with the recent completion of a four lane expressway to Dartsedo (Kangding in Chinese) from Ya’an at the foot of the Tibetan Plateau, dramatically cutting travel time from Chengdu (and Wuhan) to Dartsedo and Tawu. The virus now has expressway access all areas privileges.

The spread of contagion so far from Wuhan so alarmed officials that intensive contact tracing resulted in identification of the source, and of the proliferating number of infections. By mid-February 2020 county cadres explained to Sichuan Daily the main source was a driver who travelled widely across Sichuan in the first half of January, arriving in Tawu 18 January, spreading the corona virus to several sexual partners along the way.

One month later, zealous contact tracing meant “339 people in close contact had been subjected to centralized isolation medical observations, and 1908 general contacts had been subjected to home medical observations. All 8463 key people who were in close and general contact, regardless of whether there were symptoms, were sampled in a rigorous and responsible manner, and intensified PCR nucleic acid testing. The working method changed from waiting for the onset to confirming the diagnosis, and to proactively inspecting due diligence. The purpose is to lock the infected person in the shortest time and treat it in a timely manner; to identify close contacts and to focus on medical observation to prevent infection; to carry out home isolation medical observation on general contacts to prevent spread.”

By then there were 62 confirmed corona virus case in Kandze prefecture, 57 of them just in Tawu county. Linguist Sonam Lhundrop, from Tawu/Daofu, explains how it all happened: “In the 1980s, when the local economy first opened to the outside, Daofu became home to a booming timber industry. Although the lumber companies were owned by outsiders, people in Daofu exploited this opportunity by transporting logs to Chengdu. Then, when this industry was closed down in the early 2000s by strict environmental regulations, many Daofu people stayed in the transport industry, working for local mines and other industries. In this context, it is certainly significant that both of Daofu’s ‘patient zeros’ were local people who had been travelling for business immediately before they brought the epidemic home. It is perhaps a lack of local economic opportunity, rather than a fatal character flaw, which has wounded the weanling, and left this place and its people particularly vulnerable.” Tawu in the local language means a weanling, a young horse only just weaned.

The global blame game, which preoccupies so many folks, occurs within Tibet too. Sonam Lhundrop reports that nearby Tibetan communities blame Tawu people: “In WeChat discussions, many Tibetans have interpreted Daofu’s misfortune as karmic retribution for inhabitants’ supposed lack of piety, as reflected in their economic activities: many Daofu Tibetans are traders and entrepreneurs.”

[1] Warren W Smith, Tibetan Nation, Westview, 1996, 565-6

[2] Emily Yeh, Taming Tibet, Cornell 2013