HOLDING CHINA TO ACCOUNT FOR CLIMATE CHANGE

When you talk with European diplomats about China and climate change, they sigh. Not only have China’s fast rising emissions negated all of Europe’s efforts at cutting emissions; China berates Europeans who raise the issue, calling them imperialists using climate as an excuse to try to hold China back from its rightful place as a rich country. To this accusation, the Europeans can only say, weakly, that their imperialist era was a long time ago.

On the other hand the Tibetans can, and ought to question China’s proclaimed right to pollute, and cannot be accused of imperialism or double standards, as the Tibetan Plateau suffers more than anywhere inhabited, from rapidly rising temperatures. The climate change that is desertifying much of Tibet most definitely was not caused by the Tibetans, which should give them a valid speaking position.

As the planetary Third Pole, the Tibetans have a direct stake in the outcome of the Paris climate negotiations, and a unique insight into China’s motives, strategies and impacts. What can the Tibetans say?

First, they can point to China’s use of a huge portion of the Tibetan Plateau as nature reserve and national park, nominally dedicated to carbon capture, by excluding grazing animals and pastoralists. Most of the protected areas in China, which legally exclude human use, are in Tibet, giving China a positive story to tell the world about how it offsets the pollution from its factories and cities, by capturing carbon elsewhere. This claim gives China a lot of cred.

Global databases of protected areas take China’s red lines excluding Tibetans from the best pasture lands as a big plus. China gets nothing but praise from professional conservationists who applaud the locking up of these alpine meadows of the Sanjiangyuan National Nature Reserve (SNNR), and fail to notice the cost of exclusion borne by the pastoralists. A 2015 publication of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) actually swallows China’s propaganda without blinking: “In 2003, the SNNR was made a national nature preserve covering an area about the size of Germany. At the time, the central government invested 7.5 billion yuan (US$ 1.2bn) to preserve the full ecosystem with all its flora and fauna, and to maintain the livelihood of the diffuse Tibetan communities living within its borders.” Hundreds of thousands of displaced Tibetan pastoralists, herded onto distant concrete settlements on subsistence rations, in internal exile from their ancestral pastures, know that reality is different.

DO GRASS AND ANIMALS CONTRADICT EACH OTHER?

Tibetan pastoralists also know that grazing, grass, animals, carbon capture and sustainability go together, and are not mutually exclusive. China, failing to understand the basic dynamics of its unfamiliar grasslands, insists that “there is a contradiction between grass and animals.” This crudely Marxist dialectic formula denies the possibility of a grazing economy, anywhere worldwide. This dialectic follows a zero/sum dualistic logic: the more animals you have, the less is the grass; conversely, the fewer animals you have, the greater is the grass. You can’t have both. The Tibetans have for the past 9000 years proven you can indeed have both grass and animals: the secret is mobility, always moving on before the grass is exhausted, giving it time to grow again.

The “contradiction” between grass and animals was made official in 1987, at a National Work Conference on Livestock-Raising Areas, by Du Runsheng, who warned that the reforms of the 1980s, returning yaks, sheep and goats to pastoral families, “destroys the grasslands that are the foundation of their existence.”[1] Du Runsheng, rightly hailed as the architect of China’s rural reform program, who died in 2015, was ignorant of the basics of grassland production landscapes, as are most Han Chinese.

China calls the pastoralists displaced by conservation “ecological migrants”, who have voluntarily surrendered their food security, land tenure rights and lost their livelihoods for the sake of the planet. This positions China to call on the world to pay the displaced pastoralists, relieving China of ongoing responsibility for their survival as urban fringe dwellers. As leader of the world’s developing nations, China is keen to see the Paris negotiations embrace and finance transfer payment packages. China promotes concepts such as payment for environmental services (PES) in which upstream communities providing pure water for those downriver get compensation for foregoing development. China is also enthusiastic about REDD+, another Paris jargon acronym, meaning reducing emissions from deforestation and degradation. Both PES and REDD+ are great ideas if they establish a mechanism for rich countries to assist poor countries and communities on the frontline of climate change. But in China’s hands, PES and REDD+ become excuses for displacing ever more pastoralists from the best pastures of the Tibetan Plateau.

CHINA’S RIGHT TO POLLUTE

Tibetans in Paris can also ask the world to see the bigger picture. China still calls itself a developing country, entitled to special concessions and exemptions; yet it is also by far the world’s biggest polluter, and insists on the right to grow as fast as possible. China burns as much coal as the rest of the world combined. These are facts. In Paris, there are many conservationists, governments and international agencies desperate for a deal, talking up the hopeful prospects, willing to overlook China’s hardball stance. After the failure of the last attempt at a global treaty on climate change, in Copenhagen in 2009, it is understandable that many now assembled in Paris are willing to overlook China’s double standards, if it helps get an agreement, even if it is not legally binding, nor is it a treaty, nor is China committing to any specific reduction in emissions.

In Tibetan operas, as the plot gets messy and complicated, a bright green parrot often appears on stage, to tell the truth. That parrot, borrowed from Indian mythology, may enter the Paris stage to remind the world of inconvenient truths when everyone is hoping any agreement is better than none.

The truth is the pledges made by China do not require any reduction in emissions at all. What China has pledged (and encouraged India to also adopt) is merely to reduce the energy intensity of its production, per unit of GDP. This will happen naturally, as the services sector grows, as China’s citizens start consuming more, retail spending more, buying more sport, entertainment, health, education and financial services. The more China becomes a consumer society, the more readily heavy manufacturing becomes a smaller proportion of GDP, and China fulfils its pledge effortlessly, without any actual reduction in carbon emissions.

When Westerners say such things, China goes on the attack: you rich folks have polluted the skies for centuries and got rich; now it is our turn. You can’t accuse us of pollution when you consume what we make. That’s a valid point.

China cannot accuse Tibetans of an imperialist double standard, of plotting to deny China what Tibet already enjoys. The Tibetans remain poor, remote, marginal and largely unindustrialised. Tibetans are on the receiving end of accelerating climate warming: not only glacier melt but permafrost shrinkage leading to wetlands drying up, with loss of habitat for migratory wild birds as the water meadows dry, exposing peatlands to fire, releasing methane to the atmosphere, a gas far more potent in exacerbating climate change than carbon dioxide.

CHINA GOING GREEN?

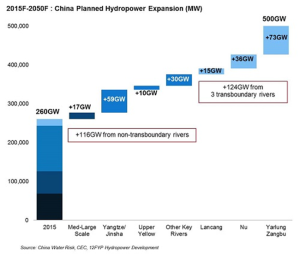

The optimists in Paris, in the hope that any agreement is better than none, seize on China’s embrace of a “green” economy, as proof that China is now a good global citizen. They often ignore what China means by its slogan of “building an ecological environmental civilisation.” In reality, this means shifting the heaviest of polluting industries far inland, to Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia and the foot of the Tibetan Plateau. Those smelters, power plants and resource extraction enclaves increasingly rely on the rich mineral endowments of Tibet, Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia, plus the waters of the great rivers that flow from Tibet, plus the hydropower China can generate as the rivers descend from the Tibetan Plateau. China has great plans to divert water from south to north, and send electricity from west to east. In each case, the starting point for sourcing water and hydro-electricity, is Tibet.

China’s “ecological civilisation” construction still ranks behind economic growth. Officially, China’s 13th Five-Year Plan, covering 2016 to 2020: “planning objective is that by 2020, China will enter the ranks of high-income countries. Plan is to build a comprehensive well-off society by 2020, GDP and per capita income should be more than double 2010. In 13th Plan the main task ranked first is to maintain economic growth, followed by the construction of ecological civilization and alleviation of poverty.”

Tibet is the planet’s high ground. The planetary high ground is so elevated even the jetstream must deviate around it. An island in the sky as big as Western Europe, Tibet has been peripheral to the global climate agenda only because Tibetans face so many difficulties when they try to speak for themselves. It is time we heard from the people of that high ground.

[1] Du Runsheng, Reform and Development in Rural China, St.Martin’s Press, 1995, p 191