A blog series on grassroots village development and conservation partnerships between Tibetans and the few outsiders who deeply immerse in seeing through Tibetan eyes: featuring two women, warrior Pamela Logan and Lü Zhi of Peking University.

DOING DEVELOPMENT 2020 STYLE

When China builds a huge solar panel installation in Tibet, by far the biggest in China, it is proudly announced as development, of Tibet, for Tibet, even though the electricity it generates is transmitted via ultra-high voltage power lines to Chinese cities thousands of kilometres away.

When Tibetans are displaced from their fields and pastures by dam construction, the relocated are classified as development successes because, on paper, their cash incomes have increased, even if they lost freedom and self-sufficiency and now survive on rations handed out by officials.[1]

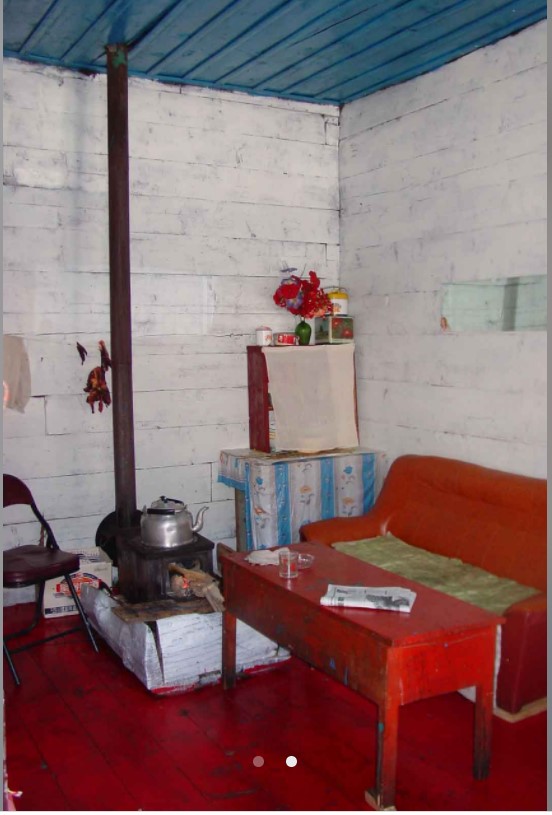

When nomads are required to relocate to urban fringes far from their pastures, are forced to sell their livestock and surrender their land tenure rights, this is called development, because in their new high density concrete blocks they are eligible for vocational education to teach them to be civilised, punctual, ready for the urban workforce. Another triumph of development.

When enormous steel cages are placed in the reservoirs behind the dam walls China builds on Tibetan rivers, to grow alien trout by the millions, then vacuum them out, electrocute, kill, gut, chill and pack them off to Shanghai, this again is called development.

Just about anything China does in Tibet outside of security state criminalisation of Tibetans voicing their needs, is called development.

This is a one-way street to a predetermined destination which China calls civilisation, moderate prosperity, discipline, modernity, hygiene, progress, human quality formation, urbanisation. These are a package. They go together. What they add up to is development, the journey from primitive to civilised, from darkness to light.

Development is delivered from above, by an all-knowing party-state that decrees what is best and requires local government to implement what is commanded and controlled from Beijing, with less and less latitude for local realities.

For such development Tibetans are not only expected to be grateful; gratitude is mandatory.

This has become the new normal in new era Tibet, as the party-state extends its nation building reach into remote areas to ensure they acquire Chinese characteristics and are assimilated into the unitary nation state constituted by the single Chinese people.

Over the eight years of the Xi Jinping new era, we have become familiar with this autocratic centralisation, in which the central leader is the author of everything, and no-one else has voice, or local initiative.

This imperative voice sweeps aside, as if it never existed, a Tibetan past that is recent, yet now erased. Tibet has so many pasts, all worth recalling, but this is a vanished past so recent we can turn to a Californian bushido warrior in the samurai tradition to enable us to remember.

THE PAST IS ANOTHER COUNTRY

Not so long ago there were many voices, Tibetan and international, on the ground across Tibet, debating, discussing, investing, experimenting with ways of inventing a Tibetan modernity that worked. Around the arrival of this century there were dozens of NGOs both big and small working in Tibet, figuring out, from the ground up, how to help Tibetans gain access to the modern world on their own terms. There were dozens of local initiatives by Tibetans, to grow more vegetables, to organise farmers into water user groups to maintain irrigation channels, to find ways of adding value to wool shorn annually from sheep, goats and yaks.

Almost all of these many, modest initiatives have been swept aside, sometimes coercively accompanied by accusations that Tibetans were getting criminally uppity, and needed to be slapped down. The security state would step in, make arrests, coerce confessions, impose sentences.

Yet for over a decade, from the mid 1990s to around 2008, Tibetan initiatives spontaneously grew, and there were plenty of international partners with access to finance and expertise, willing to negotiate with cadres and local governments and find ways to make new projects happen on the ground.

Not only have these experiments with grassroots development disappeared, the international NGOs who put years of effort into them are now silent, have moved out and moved on under pressure from the suspicious gaze of the security state. Many have even removed documentation of their past efforts from their websites, as if they never happened. So today’s new generation of young Tibetans may never know the recent history of their own phayul, the land of the fathers.

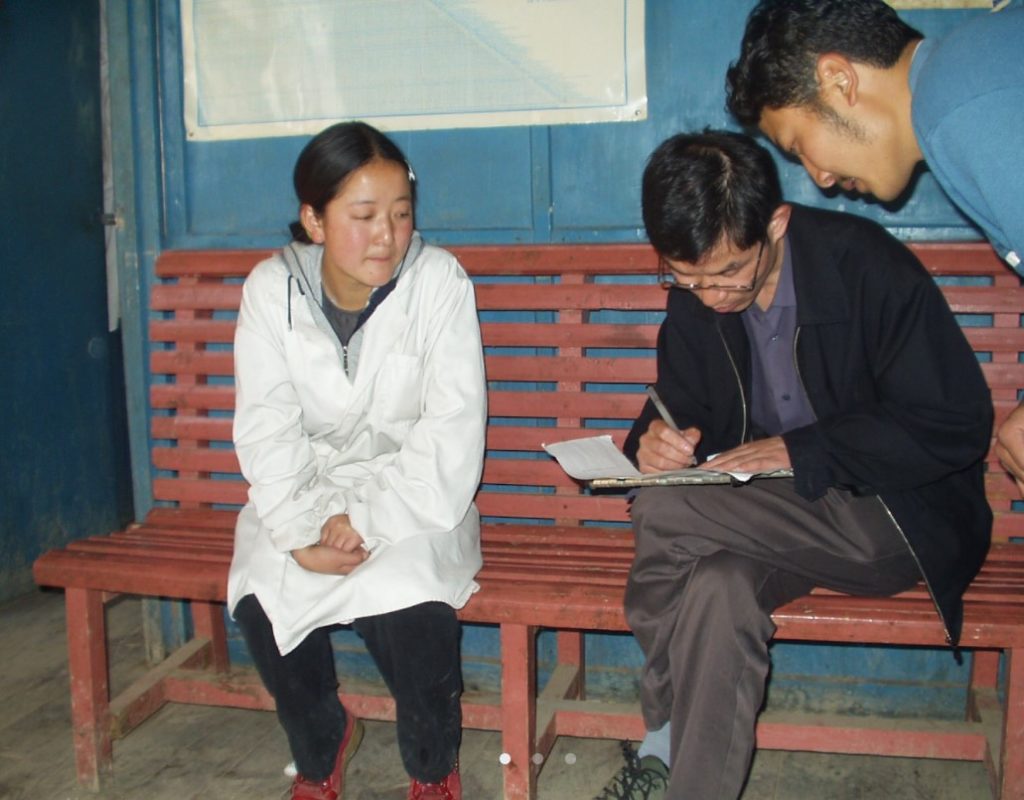

Fortunately, we do have a few thorough records of those bootstrap attempts to discover a truly Tibetan mode and pace of development, grounded in local needs and local initiatives. Pamela Logan’s 2020 memoir, Compassion Mandala: the odyssey of an American charity in contemporary Tibet, is luckily nowhere near as grand as its title. Actually, it is a winding story of discovering by doing, of Tibetan women and men working with a few Americans, making up development by doing it, trying this and that, figuring out from experience, and limited funding, what works and what doesn’t. The messiness, provisionality, contingency, trial and plenty of error are what makes this book worthwhile; and a blessed relief to the high modernity discourse of the party-state on its nation building mission to civilise the backward Tibetans.

Pamela Logan’s titles -this is her third book on Tibet- make it look like she too is on a mission. Perhaps the past books – Among Warriors: a woman martial artist in Tibet, Overlook Press 2004; and Tibetan Rescue: the extraordinary quest to save the sacred art treasures of Tibet, Tuttle 2011, had to sound dramatic in order to mobilise donors to contribute. But the warrior questing odyssey is now over. There are no more projects, classrooms, clinics, vegetable greenhouses or midwife trainings to initiate, because from 2008 China closed Tibet to the world and squeezed out the NGOs. The security state took command, and ever since, suspicion and surveillance rule.

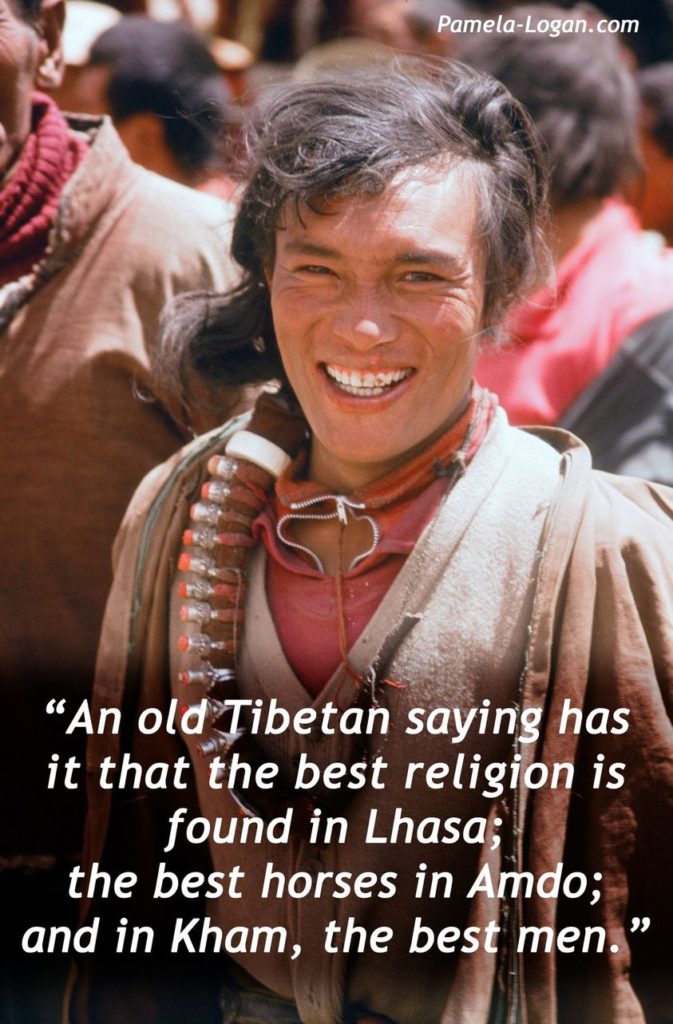

Although calling herself a warrior, and drawing on warrior strength when exhausted, she discovers the warriors she most admires are the pilgrims she falls in with, rather than the swaggering Khampas she longed for. (Among Warriors 122) She is changed by Tibet, by those early years of walking, hitching and biking a vast land. Only after those transforming encounters did she decide to return as an aid donor, doing whatever she could to help Tibetans beyond the reach or care of the state, fending for themselves against all odds.

JUGGLING WORLDS

Returning to Tibet as donor meant she had to rustle up sponsors and grants, turning her into an entrepreneur, a mediator of worlds, expectations, projections, and a professional story teller. So maybe her first book is her best, before the pressures of re-presentation required her to reproduce Tibetan lives for American consumption and donation. These days, if such immersion in Tibetan lives were still possible, the pitch would be visual, staged on social media, with greater immediacy and intimacy across cultures, bringing producers and consumers into the illusions of shared screen space.

But now only a handful of ethnographers get to immerse in Tibetan lives as Pamela Logan did in the 90s and aughties. Through them we glimpse Tibetans getting on with life. And the places that so deeply touched Pamela Logan now speak to us directly online.

What’s the point of reminiscing about 2002? Far from being contemporary, it was another world, when you could simply ask a prefectural branch of the CCP’s mass organ for controlling women if they knew anyone interested in growing vegetables, to improve nutrition in rural Tibet. The local officials of the Fulian (All-China Women’s Federation) mentioned a bunch of women they knew in remote Nyarong, in Kham Kandze, who did want help with their plan to grow edible greens (144). The Nyarongma had already tried, persuading Han women from lowland Sichuan to try planting tomatoes, lotus roots, asparagus and spinach, all of which failed in the sharp frosts of a Nyarong spring. The county Agriculture Bureau was supportive, but habituated to standard design greenhouses that cost more than either the Tibetan women, or this modest American NGO, Khamaid, could afford, so they redesigned, came up with something cheaper. It worked.

Such stories are what this book is about. Figuring it out on the go, discovering by doing. That makes this book useful for Tibetans, a reminder of local resourcefulness and an era that has passed, giving way to the panopticon gaze of the nation building state bent on assimilation and conformity. Today the Fulian, and all CCP mass organs, are under strict orders to implement Xi Jinping’s instructions, and not in any way deviate. Enterprising local Fulian chapters now must toe the line, not send inquisitive American women far upcountry to work enterprising Tibetan women.

EXPERIMENTING WITH MODERNITY

Back in 2002 Tibet was a different country, still beyond the frontier, a wild west little known to China, especially in rural areas. Cadres had been told the new slogan was to open up the west, but how? The local Agriculture Bureau pitched in, suggesting wooden frames for the greenhouse plastic frames would not be strong enough, and funded their construction with steel frames. They even built a moat round the half acre of plastic sheeted greenhouses to deter wandering livestock and thieves.

This was a time when Sichuanese farmers, too poor to make a living off their lowland plots, also sought to open up the west for themselves, constructing greenhouses too, triggering the classic ag business boom and bust cycle of glut and price crash. Tibetan demand for fresh, local vegetables was strong, but not strong enough to sustain prices as planned.

Then, just as crops were almost pickable, a spring gale wrecked the whole greenhouse experiment, trashing it all. (p174).

Readers must jump over 100 pages to the punch line: lesson learned, the hard way, which is usually the only way, especially when innovating. Khamaid moved on to build more greenhouses, much stronger, better designed for an extreme climate, for schools in Sershul and Lithang (p299). Self-sufficiency in vegetables, fresh in summer, preserved for winter, not only makes for a healthier diet and less expense, it also enables Buddhist khenpos to argue more effectively that meat eating is not necessary. From greenhouses big things grow.

Classic bottom up stuff. Which is what NGOs are good at, discovering by doing, making it up as you go along, action learning, ready to drop what doesn’t work, and apply more widely what does. That is the sort of development Tibetans want and need, as they partner the developers in figuring out what to do next. How else could Tibetans, new to the technologies of greenhouse construction, discover that wooden frames, and light steel frames are both inadequately strong when gales tear in, and rip the plastic sheeting to shreds? Clearly the local government, the bottom tier of the official hierarchy, didn’t know this either. Every one had to learn the hard way, so often it’s the only way. The important things is to never give up.

Yet the NGOs, the international NGOs with global reach, the multilaterals such as the European Union and World Bank, and the bilateral government to government development agencies are now almost entirely absent from Tibet, despite a decade or two of accumulating knowledge of what works and what doesn’t. A few narrowly defined technical assistance projects continue, such as an Australian government program to introduce new breeds of livestock, which conforms to the state’s insistence on being the author of all development initiatives, delivered top-down.

Some of the initiatives were highly organised, involving collaborations of many partners, over decades. Yet they are not only no longer present on the ground, they also leave no trace online, as if these experiments in community based development never happened.

One example is the consortium of environmental NGOs engaged in protecting biodiversity in the most biodiverse portion of the Tibetan Plateau, which is not where China is now establishing its network of national parks. The greatest biodiversity is in the rugged landscapes of Kham, the well-watered steep slopes of deep valleys and expansive pastures far above, a transition from subtropical to alpine on every valley side, highly conducive to biodiversity. For Tibetans, these precipitous landscapes, even if too steep for livestock, have always abounded in medicinal plants essential to the compounding of traditional human and veterinary treatments.

From afar, the global NGO Conservation International (CI) identified Kham as a “biodiversity hotspot”, although “hotspot” suggests a locality, not a big region, itself adjacent to the eastern Himalayas, another big region of flourishing biodiversity. What Conservation International stitched together was the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF), an umbrella engaging Chinese scientists, Chinese environmental NGOs, global philanthropies willing to finance, Tibetan communities and environmental specialists from around the world, all working together to advance protection of the Hengduan Mountains hotspot, a neutral name acceptable to the party-state.

For over a decade, CEPF created dozens of projects, initiated many collaborations, kickstarted modern Tibetan environmentalism, generated dozens of reports. No longer does the Conservation International website host the CEPF achievements. Until not long ago, a repository of those valuable lessons could be found online, many written up in 2008 as CEPF got closed down, final reports on 15 years of creative community work. Now those final reports are finally gone, collective memory is erased, no online memory remains of what retrospectively looks like another Tibet, where local initiative, global goodwill and active participation by Beijing based scientists all worked together.

Luckily, before documentation vanished, Rukor took a closer look. Further blogs in this series reveal the key role of Prof. Lü Zhi, and what community-based conservation in Tibet achieved,

This makes Pamela Logan’s 2020 recollection of community work in Tibet all the more valuable, a reminder that it doesn’t have to be today’s sterile one-size-fits-all rule by decree imposed by central leaders, badged as “development.”

One moment we are in the same lands as CEPF, responding to a village whose hillside forest has burned, seeking ways to reforest despite a lack of state support, since official funding applies only to logged, not burned forests. In the next moment, we are on pilgrimage, on horseback and on foot, into deep forests, lakes and mountains, ostensibly to learn reforestation.

207 pages later she returns the reader to the charred forest, where Khamaid has organised a replanting and six years later a quarter of the seedlings are doing well, a higher success rate than China’s preference for aerial seeding of slopes by dropping seeds from far above, without employing Tibetans to look after the exposed seedlings.

[1] Jarmila Ptackova, Exile from the Grasslands, University of Washington Press, 2020