A blog series on grassroots village development and conservation partnerships between Tibetans and the few outsiders who deeply immerse in seeing through Tibetan eyes: featuring two women, bushido warrior Pamela Logan and Lü Zhi of Peking University. Blog two.

TO CROSS THE RIVER, FEEL FOR THE NEXT STONE

Pamela Logan’s narratives meander, across landscapes, across time between the moment and a future when clarity emerges. She is sometimes immersed, sometimes detached. At times, she reveals her inner drive, to do a pilgrimage around a holy mountain, at other moments she tries objective reportage. Shifting perspectives, just like life. No sooner do we get “a hazy vision” of what reforestation might mean, than we are off into a bureaucratic maze negotiating with the Chengdu customs office to release a shipping container of wheelchairs for disabled Tibetans who had no assistance whatever from the party-state. Pamela Logan in passing reveals “we had no legal existence in China”, but her local fixer knows what is needful. The result is getting a wheelchair to a 25 year old man trapped in a soaking wet bed, who had not been outdoors in years.

The stories keep coming. One wheelchair went to “a Tibetan, a combat veteran of China’s People’s Liberation Army, he had lost a leg to a landmine during action in Viet Nam.” China’s war with Vietnam was in 1979; the man had endured a quarter century without even minimal veterans’ support, until Khamaid showed up (p105).

She cheerfully admits (p91) “we chose projects that appealed to donors and us; we had no overarching strategy.”

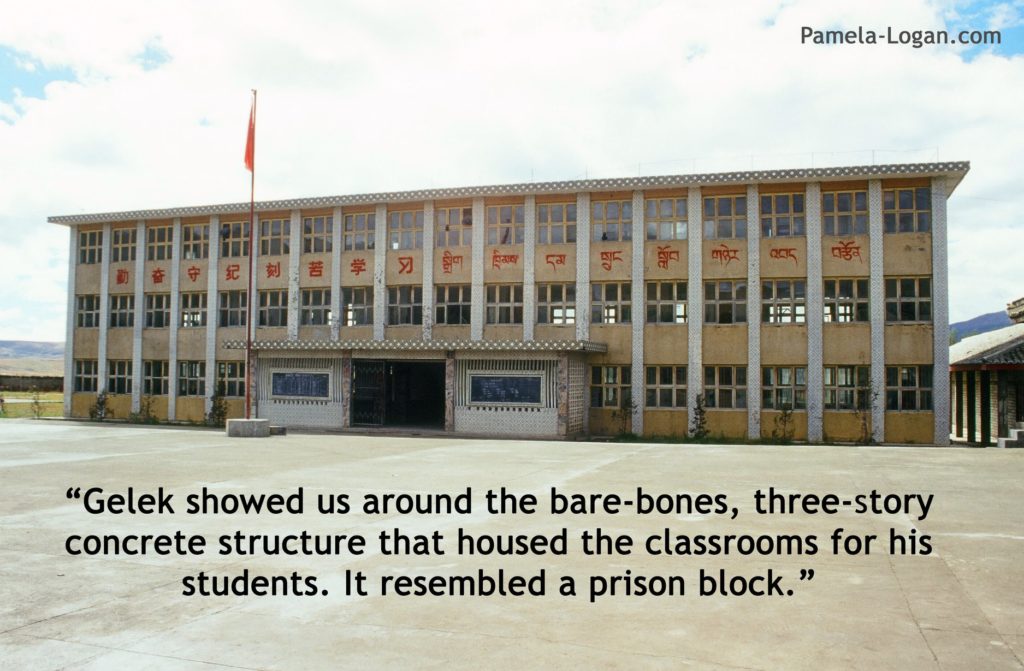

They weren’t the only ones with little idea. Local Tibetans, seeking entry points into modernity, perplexed by inexplicable switches in Chinese policy, were also unsure what could be done. Likewise the local government officials required to implement diktats issued by distant Beijing. They lacked the means, the knowledge and the community connections to do something useful.

Today’s China is embarrassed that such official indifference and ineptitude ever existed, and not long ago. Excluding foreign NGOs, as well as foreign journalists and diplomats from Tibetan areas enables the party-state to impose its master narrative, of an all-knowing, benevolent nation-state kindly raising the backward into civilisation and modernity, with all messiness removed. If Pamela Logan were still in China, her frankness would be labelled “historical nihilism”, the crime of suggesting we all make mistakes, party-state included. Today’s China is all overarching strategy, unconnected to ground realities of Tibet.

Pamela Logan established Khamaid in 1997; by 2009 it was gone. In its latter years it attracted funding from USAid, in recognition that small NGOs with an on-ground presence can achieve much that foreign governments can’t.

Khamaid stepped in at a time Tibet was for Beijing still beyond the frontier; where all that mattered to the party-state was stability. Khamaid stepped forth at a time the global Tibet movement of exile protest crescendoed, feeding into the widespread sympathy of media and human rights monitors a dualistic narrative of good and evil, of heroic Tibetan resistance to a violent party-state. The Tibet movement was on a mission, and had no interest in Tibetan bootstrap initiatives and their amateur enablers such as Pamela Logan.

Pamela Logan describes herself as a warrior, particularly of the bushido tradition. Romantic accounts of Khampa warriors, as the last honourable brigands still alive, drew her to Tibet.[1] Kham did not disappoint. Those red braided Khampa warriors on caparisoned horses won her heart. Language was no barrier. Her first Khampa lover, Sonam Gyalpo, was a passionately patriotic singer. “We had our first kiss a day later”, she coyly tells us (p 35).

“The notion of actual warriors was captivating, and Tibet had a lot of up in it.” The first and best of Pamela Logan’s three books is her warrior quest. She is frank, insightful, unafraid to reveal her inner conflicts, adept at vivid scene setting, and shows us how her embodied bushido inner strengths enabled her to recognise the embodied inner strengths of many Tibetans.

In the second book, she reinvents herself, in the American entrepreneurial tradition, as an art conservator, and in the third as an aid agency. The warrior mentality persists through all three, notably a willingness to face head-on obstacles that arise.

HOW TO BECOME AN NGO

To realise the romance, and actually do some good, she needed to raise money back in the US, on the well trod path of those who come from afar with glad tidings of the pure hearted needing our help. With plenty of photos and stories of the need for clinics and schools, of crumbling monasteries struggling to conserve precious art, of forests blackened by fire and village women aspiring to grow vegetables in greenhouses, she reached out for donations.

Her passion for Kham and her narratives of need touched many, but some likely donors held back, caught between conflicting narratives. In the 1990s exiled Tibetans found their voice, as voice of the voiceless six millions inside Tibet. It was a narrative of passive victims groaning under China’s tyranny. So black was this dominant discourse, it left no room for Tibetan initiative, or for the possibility that local Chinese cadres in Tibetan districts might permit, or even encourage, local Tibetan initiatives. Pamela Logan discovered she was advocating for projects prejudged as impossible, unimaginable and impermissible.

She was far from alone in doing development work in Tibet. Not only were the environmentalists of the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund in full swing, other NGOs such as Trace Foundation, Winrock, Bridge Fund and the London based Tibet Foundation all worked quietly, with little publicity, delivering practical projects inside Tibet. All have had to cease such work in recent years.

A MAJOR MIS-STEP

In 1999, Pamela Logan took the warrior option, of confronting the voiceless victim story head on. She wrote a furious op-ed for the Los Angeles Times, published by other papers as well, appealing to the editorial contrarian streak.

In Compassion Mandala in 2020 she now looks back (p59), and calls this A Major Misstep, but proceeds, as most memoirs do, to argue why she was right.

In 2020 we are all too familiar with polarisation, the tribal need to take sides, the dualistic fixations on one side right, one side wrong, the either/or logic of the zero/sum infects everything. That dualism did not come from nowhere; it is deeply embedded in Western culture. Some Tibetan lamas call it Abrahamic, a fault line inherited by secular modernity from unexamined Jewish, Christian and Islamic heritage.

That 1999 op-ed tackled head-on the obstacles she faced: “the foreign media has tended to act like a mouthpiece of the Tibetan government-in-exile, an organization whose overriding concern is, understandably, to regain its lost nation. Uncritical acceptance of flawed and biased information has been routine in American newspapers. Journalists have read the poorly researched work of other journalists, written more of the same and built up a demand for China-bashing stories. Such reporting sells newspapers by staying in the public’s comfort zone, shielding us from moral ambiguity; but it is mighty poor journalism.

“As president of a nongovernmental organization that brings foreign aid into Tibet, I have seen how Tibetans are hurt by the information blackout. When I try to raise money for repair of Buddhist monasteries, potential donors cite widely reported figures of 4,000, 5,000 or 6,000 (take your pick) monasteries razed by the Chinese, and are reluctant to believe there is anything left to repair. When I solicit donations on behalf of schools in Tibet, people object erroneously that schools do not teach Tibetan language and are therefore instruments of the Chinese policy of cultural annihilation. When I ran an art conservation program that rescued some rare and endangered Tibetan murals, some felt that because the Chinese government allowed this project, there must be something wrong with it, and advised one of my volunteer workers not to participate. Americans have been conditioned to believe that the Chinese are utterly opposed to any sort of Tibetan cultural or economic advancement. Accurate reporting would show this is not the case.”

Factually, she was right. She argues for complexity and moral ambiguity, but the combative samurai tone pushes yet again into right and wrong. That article made her non grata throughout the Tibet movement at the moment of its greatest flourishing. It was indeed a major mis-step.

Taking sides, Beijing versus Dharamsala, obscures complexity and the actual lives Tibetans live every day under the contempt and racism of the rulers. Righteous indignation, in the name of voicing the voiceless, in practice silences Tibetans in Tibet who must skilfully negotiate their alien rulers daily. Side taking oversimplifies the messy accommodations necessary, on the ground in Tibet, to get anything done.

APPROPRIATING THE APPROPRIATOR

One example: when a female tulku lineage of reincarnations of the ego-cutting Machik Labdron survived into the communist era, she was forced to marry and have children, and was recruited to become part of the CCP’s elaborate apparatus of legitimising its rule.[2] That makes Kalsang Damcho Drolma (in pinyin Gacang Danqu Zhuoma 尕藏丹曲卓玛), 1936–2013, a victim of communist dictatorship. However, she used that legitimacy in the new hierarchy to continue the work of a Machik Labdron. That restores her agency and effectiveness, despite all official obstacles; and when she died her obituary, praising her achievements, is an official document, issued in Chinese. Did the CCP use her? Did this reborn Great Mother use the CCP? Who is appropriating whom? Her story of inner strength is far from unique.

Out on the grasslands of Amdo Labrang -her home- disputes among pastoralists have persisted, sometimes solidifying into deadly feuds that can go on for generations, in lands historically not ruled by either Lhasa or Beijing, where there was not only no law, there was no concept of law.[3] Resolving such disputes was the work of Buddhist teachers, trusted deeply because of their exemplary lives, known to be beyond bias, able to persuade and convince antagonists through logic, reason and personal magnetism.

Kalsang Damcho Drolma met all these criteria in the eyes of her people. Her official 2013 obituary describes her wielding just such abilities: “In order to preserve this herding area’s peace and to prevent the further loss of husbands and fathers, the Gung ru Mkha’ ’gro ma had the power to rally support among the people. She used her kindness and energy to take the initiative herself to mediate the grassland conflict and end the dispute. Because they were touched by her leadership ability and the power of her strong personality, the dispute ended peacefully for both sides, and the matter was resolved with her even-tempered reasoning.”

Such stories seldom appear in exile Tibet movement advocacy, leaving only stories of passive victimhood. The six million Tibetans in Tibet, their aspirations and needs seldom attended to, are seldom heard. They remain invisible, now sealed off more than ever by China’s high modernist program of urgent urbanisation and top-down nation building assimilationist development.

In hindsight, from the 1980s through to 2008 there was a lot that could have been done to help Tibetans in Tibet to create their enterprises, to reforest, grow vegetables, build their schools and clinics, improve mother tongue literacy, add value to local speciality products and so on. Little of that happened, and now it is no longer possible. That’s sad.

Compassion Mandala is unfortunately not about contemporary Tibet. If only the lessons Pamela Logan learned from listening to and working with Tibetans in Tibet could still be acted on, guiding our wish to help. If only we could read her as our guide to doing good, on the ground, somewhere in that vast plateau.

Tibet, more than ever, is caught between the Manichean dualism of China, and that of Tibetan exile. In China’s telling, Tibet dwelled in darkness, backwardness, poverty and remoteness. Benevolent modern China has brought Tibet into light, civilisation, history, development and the promise of prosperity. In the exile narrative, all Tibetans are trapped helplessly in the tyranny of communist dictatorship, passive and unable to protect their lands, language, culture and identity from extreme coercion.

In the middle are the Tibetans, unheard on all sides, asserting agency wherever possible. Pamela Logan sought that middle, listened to the aspirations of remote Tibetan villagers, and did what she could to mobilise practical assistance. It is now over 25 years since she began that work, a decade since it had to end, and we are more fixated on good and evil than ever. Logan’s new book does enable us to glimpse the lives, hopes and fears of those lost to sight in the long shadows of today’s geostrategic great games.

Three decades of travels in Tibet and reflections for the English reading audience. Three books on Tibet, over 25 years, returning again and again to what sometimes seems to be a romantic projection, a yearning for the unnameable. Yet this self-defined woman warrior did experience Tibetan culture fully, did have transformative moments, did discover in extreme hardships of pilgrimage a transcendence that took her by surprise, yet able to convey it effectively in writing. No small achievement. Few nonTibetans have so fully entered into Tibetan mind spaces, or been so open to seeing afresh, sensitive to a posture, a gesture that subtly signals inner transformation. Alive and alert, she is attuned to the uncanny, the liminal, the awakening.

***************************

Further blogs in this series bring us to another nonTibetan woman who learned deeply how to see from a Tibetan viewpoint. Lü Zhi and a global partnership to conserve Kham as a great hotspot of biodiversity, next on Rukor.

[1] Michel Peissel, The Cavaliers of Kham, the secret war in Tibet. London: Heinemann, 1972; and Boston: Little, Brown & Co., 1973

Michel Peissel, The Last Barbarians, the discovery of the source of the Mekong. New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1997; and London Souvenir Press, 1998

Tiziana and Gianni Baldizzone, Tibet on the Paths of the Gentleman Brigands, Thames & Hudson,1995, also published as Tibet Land of Gentleman Brigands, White Star Publishers 2004; http://www.himmies.com/h1/eccentricexp_sample.html

[2] Peter F. Faggen, “Re-adapting a Buddhist Mother’s Authority in the Gung ru Female Sprul sku Lineage,” Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, no. 55, Juillet 2020, pp. 140–160. http://www.digitalhimalaya.com/collections/journals/ret/index.php?selection=1

[3] Fernanda Pirie, 2014. The Anthropology of Law. Oxford: OUP. 35-6, 159