COPPER-COLOURED MOUNTAINS

Blog 3 of 3 on the rapidly accelerating boom in China’s demand for critical minerals

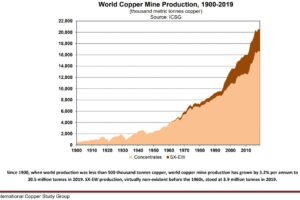

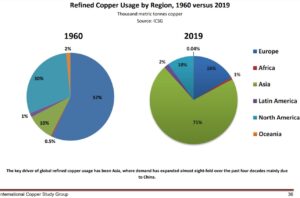

The race is on, both within China and worldwide, for dominance in copper mining. China already dominates copper refining, and now seeks to own and extract worldwide the raw ores that enable its dominance. In copper, China is repeating its pattern of dominance in the production of the metals on which modernity is built.

The announcement that Tibet is to become the location of the biggest copper mine in the world suddenly thrusts Tibet to the forefront of China’s strategy for comprehensive global dominance of the metals that make modernity. That announcement, on 26 December 2021, signals a rapid escalation in copper extraction, and an intensification in exploitation of the many copper-coloured mountains of Tibet, especially the many copper deposits close to Lhasa.

“If the project obtains approvals from the relevant government authorities, it can reach a final scale of mining and processing of approximately 200 million tons of ore per year, and will become the copper mine with the largest scale of mining and processing in the world,” says Zijin.[1]

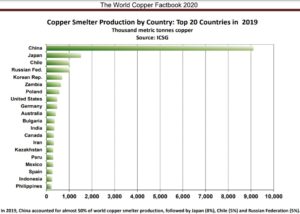

The smelter refining of mined concentrates is the most profitable part of the commodity chain, however China is now energetically moving upstream, to capture ownership of the raw materials and the mines that extract them, and concentrate them for processing in China. The plan is to dominate the entire commodity chain, from extracting raw materials, through to ore concentration and smelting of pure metals, with all value-adding done in China, no matter where in the world the raw materials come from.

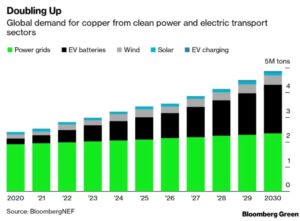

If China can dominate the entire copper production commodity chain, from mining through to fabrication, it will replicate its dominance in other metals that attract more attention because they are classified as strategic security metals. Because copper has been used for thousands of years, it is seldom thought of as a security risk if one country comes to dominate. However, copper is essential to the future of a decarbonising planet. Whether the energy future is wind power, solar power, hydro power or lithium battery vehicles, copper, in large amounts, is essential to transmit energy from where it is generated to where it is used. Investors worldwide know the future of copper is bright.

“There were 11 Chinese enterprises in the 2002 Fortune 500, not a single non-ferrous enterprise is on the list. There are 143Chinese enterprises in the 2021 Fortune 500, ranking first in the world. Among them, there are 9 non-ferrous enterprises: China Minmetals Group #65, Zhengwei International Group 68, Aluminum Corporation of China 198, Jiangxi Copper Group 225, Weiqiao Venture Group 282, Jinchuan Group 336, Tongling Nonferrous Group 407, Hailiang Group 426, Zijin Mining Group 486. In 2020, China occupies 4 of the top 10 refined copper enterprises in the world.”[2]

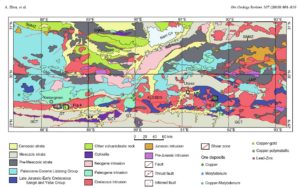

For many decades copper mining has been mostly in the Americas, especially in Chile. The biggest, by far, BHP-owned Escondida, has long had an incomparable lead, able to produce 1.4 million tons of copper metal a year. Copper deposits often occur in clusters, and Chile has six of the 14 biggest copper mines in the world. Tibet, especially the districts around Lhasa, is now defined, in Chinese eyes as a tantalising grouping of 40 copper deposits, a few already mined with many more awaiting extraction. Not only is central Tibet emerging as a highly attractive mineralised district, one single mine is to be the world’s biggest.

Tibet, especially the districts around Lhasa, is now defined, in Chinese eyes as a tantalising grouping of 40 copper deposits, a few already mined with many more awaiting extraction. Not only is central Tibet emerging as a highly attractive mineralised district, one single mine is to be the world’s biggest.

Bigger than Chile’s Escondida? That’s a big ask. But the boastful 26 December 2021 announcement says just that. This blog evaluates that corporate claim. But first a bit more background.

FROM MOUNTAIN TO METAL: STAGES OF COPPER PRODUCTION

Mining and refining do not necessarily go together. This is puzzling, since the amount of copper contained in the rock that is blasted and dug out is seldom more than two percent, so enormous amounts of rock must be extracted to obtain the copper, plus other valuable metals in even smaller amounts. This inescapable basic reality means that there has to be an intermediate stage between mining and refining. This is concentrating. Chemical concentration using sulfuric acid can produce a concentrate that is usually 23% copper, a big improvement on two per cent; but it still means 77% of the concentrate will become waste, when pure molten copper pours off a smelter.

Inevitably, a mine is also a concentrator, they go together at the mine site, which requires the ore to not only be dug but then ground up into powder so the sulfuric acid can do its work. That makes for copper mines to have a huge impact on the surrounding countryside, both because enormous amounts of rock have to be taken from the earth, and because three quarters of all rock processed in a concentrator ends up as waste, to be secured on site, forever.

To an outsider, it might seem logical that the next step, of refining concentrates into pure metal, should also be done at the mine, in a smelter. After all, the concentrate still contains ten times as much waste as metals worth extracting and purifying. Why haul all that a long, long way? But mine designers don’t think like that.

Building a smelter is expensive. It needs reliable access to lots of energy. It is the value adding stage that maximises profit. It needs continuous supply from a range of sources, not only copper concentrates but also scrap copper to be recycled, which in turn favours locations with access to the global traffic in copper scrap.

So for decades, worldwide, the mining and concentrating of copper ore have been separated from refining, initially by hundreds of kms, now by thousands of kms, sometimes as much as 15,000 kms of rail and ship transport, as is the case with China’s newest copper mine in Congo, which is refined in China.

CARBON-INTENSIVE COPPER PROCESSING IS NORMAL

That used to make economic sense in a globalised world where scale and efficiency were all that mattered. As long as the production chain could be engineered to minimise the dollar costs of extraction and processing, the fine tuning of global commodity logistics chains could ensure maximum productivity for minimal cost, which keeps shareholders happy.

China did not invent this pre-pandemic world of endless fossil fuel supply, globalised supply chains and environmental impacts not showing up in bottom line calculations; but it did intensify it, take it to extremes. In a pandemic, decarbonising world where China and the US are decoupling, this operating model might seem questionable, but it remains the norm within the global mining industry. China has made the heavy global footprint of copper heavier.

FOOD MILES, COPPER MILES

The copper pipe that brings clean water to your apartment is beneficial. It won’t rust or tarnish, could function for a century with almost no maintenance. But if it came from 15,000 kms away, in a ship laden with ten times as much waste as copper, that then has to be dumped somewhere, questions arise. In mineral economics these are externalities, of no concern to the miner/refiner.

If anyone has responsibility to handle those externalities, it is the state, which legislates to reduce fossil fuel energy use, reduce air and water pollution, and ensure mining wastes don’t pollute.

In China, mine and smelter operators and the state are uncomfortably close, both because mining corporations are often state-owned and because the miners are at the forefront of China’s global reach and power projection. The party-state does all it can to favour, incentivise and subsidise the leading miners to get ever bigger, dominate global supply chains, become national champions, dragonheads of China’s emerging super power status.

In this global game, Tibet might seem a sideshow. Not when it comes to copper. The copper province both east and west of Lhasa positions Tibet in a global league of global-scale deposits, requiring global scale investments and extraction plans.

For China, Tibet is just as remote as Peru, Zambia or Congo, and the same logistics apply. In the mining corporation boardroom, and in central planning offices in Beijing, Tibetan deposits sit alongside the Congo as the next big project; their key decision is which comes next.

CHINESE MINING, WITH TIBETAN CHARACTERISTICS

Until now, only four of the 40 copper deposits of Ȗ-Tsang have been mined, for good reasons. Extraction, crushing and concentrations costs high, as in any remote area. Deposits that are mountains, often at altitudes above 5000m, in permafrost, are a special challenge. How to dig in frozen earth? How to crush, how to concentrate, when electricity must be sourced from afar? Above all, what to do with the wastes left over after ore concentration, on a frozen mountain slope? If you are planning to dig up 300,000 tons of rock every6 day, for 30 years, that’s a massive problem, since 235,000 tons of the 300,000 must remain on site forever as waste tailings, day after day.

Copper mines in the mountains have a dramatic history. In the high rainforests of Papua New Guinea the terrain at Ok Tedi was deemed too steep for safe tailings storage, and all wastes were swept down the Fly River, ruining an entire ecosystem, until the scandal grew to the point that BHP had to abandon the entire project.[3] On Bougainville island, where it rains every day, the locals were so dismayed at what copper tailings did to the Jaba River, they revolted and closed the mine. In Indonesian Papua the Freeport McMoRan Grasberg mine continues to be one of the biggest worldwide, because the Indonesian military, which profits enormously from mining, ruthlessly represses indigenous protest.

RISKY BUSINESS

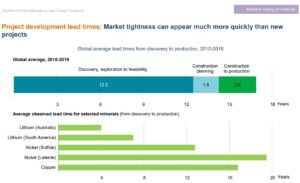

Mining is risky, not only for the wildlife and the local communities, but also for the miners. Metal prices are volatile, with cycles hard to predict. While metal prices fluctuate, sometimes greatly week to week on trading platforms, sometimes hour to hour, the planning, constructing and operating of a large scale mine is on a very different cycle, measured in years, sometimes decades. The right time to build that mine is always yesterday, but yesterday and yesteryear when prices were low, boardrooms, answerable to investors, held back. It’s a chronic problem. Shareholders demand quick profits; mining engineers need decades to design and build a mine.

When supply only slightly exceeds demand, as was the case with lithium in 2021, prices can fall a lot. When supply slightly lags demand prices can rise a lot, as with lithium in 2022. Volatile.

Understandably the miners prioritise security and stability of supply, given the cyclical uncertainties they must face. Likewise the party-state is also fixated on security and stability as its top priority, which requires repressing dissent, petitioning and protests quickly and decisively. Silence.

EMBRACING RISK

With all the powerful players -the miners, party and state – all chasing top-level stability design, seeking a critical path that minimises costs, maximises profits and guarantees commodity flows, it may be surprising that Beijing does allow practices which exacerbate volatility. Commodities trading by wealthy gamblers, usually betting other peoples’ money they manage, on the promise of making that money make more money, is a big deal in China. Their momentary fintech enthusiasms and exuberances, their fears and fear of missing out all exaggerate the swings in metals pricing.

The party-state dislikes the “disorderly” expansion of capitalist wealth accumulation, but the boom/bust cycles of mining and metals production are inherently disorderly, if only because it takes many years to build a mine, and only moments to bet on volatile metals price futures.

For decades those commodity speculator profits were garnered by traders based in Switzerland and other tax havens, which Chinese regulators found frustrating. So the venerable London Metals Exchange was bought out by Hong Kong, and China now has its own armies riding the volatile waves of futures trading, making astute insider guesses enabling them to profit both when metal prices go up and down. It’s China’s turn. [4] The economists of the central bank know full well these arbitrageurs make the price swings more exaggerated. They complain loudly that this is unpatriotic. But there are few regulatory curbs on the irrational enthusiasms of the bettors.

Zijin Mining 紫金矿业 listed as 601899 on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, and 2899.HK on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange is a pioneer not only in plunging into the sea of global extraction, but also the financialisation of copper and other metals, with a fine-tuned ability to make money whether metals prices are rising or falling, by. Betting ahead of the curve. Smart money hard at work.

HYPING A SUPER-CYCLE

The elusive copper-coloured paradise that most bewitches the metals traders is the possibility of a “super-cycle.” In a super-cycle the usual boom-bust no longer applies, it’s an unending boom, in which prices jus go up and up and up, rather like the bitcoin and NFT stories. A super cycle, ideally you buy in early, then hang in and resist the temptation to cash out, as prices will continue to rise further, as does your fortune.

There was something like a metals supercycle 10 to 20 years ago, which persisted even through the 2008 global recession. Now supercycle talk is back again. Excitement is building. ““You have an EV supercycle and you add a real commodity supercycle on top of that — it’s game on for the miners,” said Simon Moores, managing director at Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.“

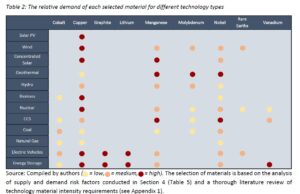

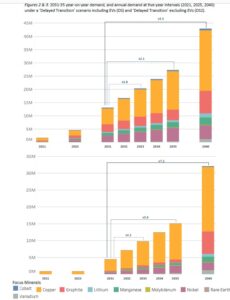

The copper “supercycle” is driven by the crucial role of copper in every new/green/renewable energy technology you’ve ever heard of. “Alternative energy systems have a high—and often, unappreciated—materials intensity, of which copper is a major constituent. For instance, every thousand battery electric vehicles (BEVs) produced can require approximately 83 metric tonnes (MT) of copper (well more than triple conventional vehicles at 23 MT), while wind turbines incorporate 3.6 MT of copper per megawatt (MW) of output, photovoltaic cells 4-to-5 MT per MW, and flywheels for pumped hydropower 0.3-to-4 MT per MW.

“To quantify the relationship, 30,000 BEVs can consume as much copper as a skyscraper, like the 600,000 square meter Yi Fang Center in Shenzhen (Chinese buildings are close to 50% of global building stock). To turn over just 1/3 of the global passenger vehicle fleet (China currently comprises about 1/3 of passenger vehicles in operation) would require placing into service more than 300 million BEVs. These could collectively contain 20 million tonnes of copper, almost equal to current annual total world consumption, or about a fifth of the entire copper metal stock that analysts estimate currently sits in Chinese buildings and vehicles.

“With alternative energy systems five times more copper intensive on average than their conventional counterparts, the push away from fossil fuels could strain global copper supplies, perhaps significantly. Energy transition goods will have to compete with traditional demand sources precisely as the pipeline of new copper extraction projects reaches its lowest level in the last century and risks compressing supply.”

KATANGA OR MELDRO GUNGKAR, CONGO OR TIBET?

All of this matters in Tibet. Whether Tibet becomes a province of intense mineral exploitation, like Katanga province of the Congo, depends on all the above issues. Katanga or Ȗ-Tsang is the real-world choice facing the board of Zjin mining as it decides where to scale up next, in the expectation that copper is now entering a supercycle that will make a lot of people super rich.

The slow pace of intensification of copper extraction from Tibet will soon quicken. It has taken decades of central investment in infrastructure to effectively link Tibet to lowland China, where the copper demand is strong. The plateau, the size of Western Europe, has remained frontier territory, or beyond the frontier, a land alien to Han Chinese expectations of what is normal, in almost every way. If only four out of 40 big copper mines of central Tibet are currently working at extraction, that is not unusual. In 2020 the smart money folks at Standard & Poors Market Intelligence berated the global mining industry for its hesitancy to spend capital on opening new mines: “This year’s analysis of major copper discoveries has identified 224 copper deposits discovered over the 1990-2019 period, containing 1.08 billion tonnes of copper in reserves, resources and past production. Of the 224 copper deposits discovered, only 16 have been found in the past 10 years and only one since 2015. While this underperformance is mostly the result of less exploration for new discoveries, a portion of the shortfall reflects the additional exploration still required at recent discoveries to expand the endowment above our major discovery threshold.”

Now the pace is picking up, including in Tibet. The possibility that in a few years there could be 10 or 20 substantial copper mining operations around Lhasa is real. Lhasa could become a mining hub town, the location for corporate offices, labour recruitment and mobilisation, and royalty revenues that give the TAR government some alternatives to endless subsidies from Beijing. These are real possibilities Tibetans should be thinking about.

As extraction accelerates, no longer is it Congo or Tibet. Now China wants both.

| Zijin Mining, the giant that can stabilize the copper market with huge mine in Tibet, Noticias Financieras, |

| 30 December 2021 |

[2] Kang Yi, Review and Prospect of China’s Nonferrous Metals Industry after China’s entry into WTO, Shanghai Metals Market, 4 January 2022

[3] Colin Filer And Phillipa Jenkins, Negotiating Community Support for Closure or Continuation of the Ok Tedi Mine in Papua New Guinea. 229 in Colin Filer And Pierre-Yves Le Meur eds, Large-Scale Mines And Local-Level Politics, ANU Press 2017, free download: https://press.anu.edu.au/publications/series/asia-pacific-environment-monographs/large-scale-mines-and-local-level-politics

[4] Yang Dian and Ouyang Xuanyu, The Rise and Impact of Financial Capitalism: A Sociological Analysis of New Forms of Capitalism, Social Sciences in China, 2020,Vol. 41, No. 4, 24-43