TIBET AND GLOBAL SOUTH RESOURCE NATIONALISM

Blog 2 of 3 on the rapidly accelerating boom in China’s demand for critical minerals

There are countries rich in minerals that have decentralised power, are struggling with the legacies of recent conflicts and civil wars, and the national government is unable to simply apply state violence to attack citizens. Indonesia, Bolivia and Colombia come to mind. In ways, as they struggle to deal with past traumas, in order to advance development, perhaps they share some similarities with Tibet. Like Tibet they are now struggling with China’s hunger for their minerals, critical to electric car battery manufacturing.

At a national level, their often weak governments understand their mineral wealth could generate much greater wealth if the full processing is done onshore, and the nation can export batteries rather than lithium, copper wire rather than copper concentrate slurry, nickel metal rather than pulverised rock. This is resource nationalism.

In practice, many developing countries have tried, and stumbled, often failing to attract sufficient investment capital to get such integrated operations up and running. Just ask the Mongolians.

Now it’s the turn of Bolivia, Colombia and Indonesia to make resource nationalism work. It’s an uphill climb, at a time when rising US interest rates tempt hot money to exit developing economies because rates of return in the US are now higher, and less risky.

China is intensely interested in all of these countries, and operates a civil-state fusion strategy of state support for finance, belt and road sweeteners, such as constructing a sports stadium for the masses, along with contracts that favour Chinese corporations at every turn. This is pitched as beneficial for all, a classic win-win.

INDONESIA’S RESOURCE NATIONALISM

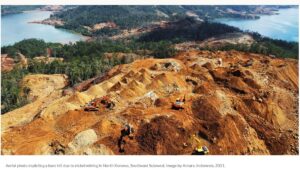

However, Indonesia is big, and well-endowed with minerals, and has a government that has been willing to forbid expert of raw, unprocessed minerals unless and until the miners invest in a local processing plant to make pure nickel metal for export back to China, in great demand for making batteries for electric cars. Indonesian nickel and Tibetan lithium are the core of battery making in China, and both are likely to be in short supply, not only in the short term, but even in 2040.[1]

But over two decades ago, Indonesia’s community protests toppled the dictatorship, and then decentralised power to local levels, to make sure dictators could not rise again. For Indonesian resource nationalism, and for China’s extraction ambitions, this localisation of power is a headache. Local communities can and do protest that now only is their mineral endowment extracted, it is processed nearby in polluting smelters, and the wastes are dumped locally.

Bolivia and Colombia, both much smaller than Indonesia, are not as well placed to insist on local value adding of raw crushed rock pulled from the earth. Moreover they must grapple with the power of the armed narco-traffickers and the legacies of long running conflict. Their dream of exporting lithium batteries rather than powdered lithium precursors, might be hard to realise.

China’s role in these countries is a story worth exploring, as it sharply illustrates how China treats Tibet.

In Indonesia, on the nickel-rich island of Sulawesi, “Kurisa has been home to the Bugis Wajo people for generations. Houses are propped up by rows of wooden stakes so that they stand over the Banda Sea, with fishing boats docked underneath. Traditionally, the men go out to sea to bring home red and white snappers, tuna, octopus, and other seafood for the women to cook, and children are encouraged to fish from a young age. A few hundred meters from Kurisa is a coal plant that powers the nearby Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park (IMIP), a massive industrial complex occupied mostly by nickel-related industries and managed by a Chinese-Indonesian joint venture. Residents complain that IMIP’s operations, which started in 2015, have led to polluted waters.”

Maybe a generation ago, the solution would have been to send in police and paramilitary, shoot a few people, and quell the protests. But that is possible today only in remote provinces run by the military, not in Sulawesi. Then, early in 2023: “Two workers were killed in clashes and rioting at an Indonesian nickel smelter at the weekend, officials said on Monday, as hundreds of security personnel were deployed to maintain order after a protest over pay and safety spiralled out of control. National police chief Listyo Sigit Prabowo said 17 people were suspected of vandalism among 71 detained over the incident, and more than 500 members of the security forces had been deployed to secure the area, with more reinforcements coming.”

Another complication is that the Chinese-built nickel refinery on Sulawesi doesn’t actually produce nickel metal of sufficient purity to be tradable as a globally fungible commodity that can be monetised on any commodity exchange. The output is nickel matte, an intermediate product with many impurities, not suitable for battery makers. Nickel matte may be anywhere from 30% to 70% actual nickel, and the Indonesian output is at the low end. This means it can be sold only to a processor capable of producing pure nickel, which so happens to be in China.

NICKEL BOOM & BUST

A further and major complication is that the dominant Chinese nickel miner in Indonesia, Tsingshan, in 2022 gambled heavily on future nickel price movements, and spectacularly lost what had seemed like a smart gamble. Tsingshan is headed by a famous risk-taker revered in China (until 2022) for his bold risk-taking that was putting China on the global map. Xiang Guangda 向广大may be a gambler, but was also in the ideal insider position of knowing exactly when his Indonesian nickel matte would become available, in such quantities that for a while supply would exceed demand, and prices would fall, part of the cyclicity of mining. That’s why in China he is known as 大人物, da ren wu, big shot.

What Xiang Guangda, despite his inside knowledge, didn’t see coming was Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, which knocked Russian nickel out of world markets, resulting in a price spike, and Xiang Guangda was ruined, suddenly billions of dollars in debt. So big was the loss, it threatened the survival of not only Xiang Guangda’s empire but also the platform where he made his gamble, the London Metal Exchange (LME). Despite its name and venerable backstory, the LME is Chinese.

In order to save both itself and Xiang Guangda, the LME abruptly cancelled all transactions of the day the wheels fell off, to howls of outrage from all the hot money men who stood to make their fortunes ever bigger by gambling nickel prices would rise.

The headlines says it all: Traders in uproar over LME. This is capitalism red in tooth and claw, resolving its bubble bursting by simply cancelling all trades, as if nothing had ever happened, nothing to see here. The crisis happened 7 March 2022, two weeks after Putin’s tanks rolled towards Kyiv. Many of the world’s biggest banks and sharpest traders were on the line, many as debtors who had loaned money to Xiang Guangda to gamble with. Billionaire behaves badly when bearish bet backfires. Most unusual. As usual, the central party-state seriously considered bailing him out.

Enraged traders reached for the ultimate insult, rebranding the LME the Soviet Metal Exchange. But for Xiang Guangda, it was existential. Not only could Xiang’s empire collapse, so too could Indonesia’s hopes of making nickel metal pure enough to make batteries and eventually electric cars. If that collapsed, China’s plans for a captive offshore source of nickel would collapse. The Tsingshan empire had sunk billions into mines, refineries, ports, marine terminals, airports and power stations, and was celebrated in China as a national champion of the Belt and Road. Since China has little nickel ore, and Indonesia has a lot, colonising Sulawesi was the solution. A decade ago, when Tsingshan started investing in Sulawesi, nickel was needed primarily for making stainless steel. Batteries came later. Xiang’s Tsingshan was so dominant, other companies, including battery and electric car makers such as CATL had no choice but to allow Xiang Guangda’s Indonesian treaty port a substantial slice of ownership. That was the price of entry for any latecomer. Xiang Guangda is a monopolist.

Xiang is from the most Christian city in China, Wenzhou, which has cultivated a go-getting entrepreneurial style, and is famous for producing big shots.[2] He couldn’t be allowed to fail; someone else had to blink.

Maybe that’s why the illustrious London Metal Exchange outraged the most predatory of capitalists and bowed to Xiang Guangda, nullifying his failed gamble. The lawsuits, as big money sues big money, will go on for years. Months after this meltdown, the Financial Times reported: “The short squeeze risked causing damaging losses for the Chinese group, which produces large quantities of lower-purity nickel in Indonesia that cannot be delivered against the LME nickel contract, and its lenders including JPMorgan. The market turmoil threatened to trigger a systemic crisis. The LME, which is owned by Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing, is under pressure for suspending trading and cancelling trades from financial investors. Hedge fund Elliott Management and market maker Jane Street have launched a lawsuit against the LME, claiming damages totalling almost $500 mn.”

This story tells us much about where mining fortunes are made. It is of course necessary to build the mine, the processing plant, the long haul to Chinese smelters, but the real money comes from financialising those investments, playing with other people’s money to double, treble, quadruple your worth, simply through insider knowledge.[3] It is not hard to imagine Tibet’s minerals endowment similarly gambled and metastasized.

CHINA IN BOLIVIA AND COLOMBIA

Colombia and Bolivia have also attracted Chinese miner investment, with the same hope of host governments of turning their ample lithium deposits into batteries and electric cars. These are conflict zones, where China is trying to thread its way through the ongoing contestations, such is its hunger for the conflict minerals, mostly lithium, which can be extracted there. As you read this story, imagine if this was happening in another conflict minerals zone: Tibet.

European, American, Canadian, Australian mining giants are sometimes hesitant to invest in conflict zones, for fear of reputational damage that affects share price and capitalization; but there are many who do plunge in, when the price is right. Right now the price is right for lithium and copper, wherever deposits are found. What holds back Western investment, thus letting Chinese in, is not conflict minerals but critical minerals. Western governments are increasingly subsidising Western-based mining corporations to mine and process critical minerals onshore, within the sovereign territories of the West, on national security grounds. That leaves developing countries with only China willing to invest.

In reality critical minerals are often conflict minerals, especially in Tibet, Congo, Peru, Colombia, Bolivia and now Indonesia, at least in the Sulawesi and Papua provinces. Copper extraction from Papua by Freeport MacMoRan is enforced by militarised criminalisation of the local indigenous Melanesian population, uncannily akin to Tibet.

Yet not all conflict zones are treated equally. Where conflicts are ruthlessly quelled by state violence, and news seldom leaks out, it’s business as usual. Even in Congo, the unscrupulous miners who remain are now trying to attract the multinational miners back, now that the profits are so high, as the electric car market accelerates.

So when Bolivia aspires to do more than scoop lithium salts from dry lake beds, and make batteries, maybe even electric cars, who can it turn to for expertise and above all, capital to invest in making it happen? In today’s world, only China.

Bolivia and Colombia have nothing like the market power of Indonesia, being much smaller, unable to raise capital to realise their resource nationalist dreams, weakened further by deep internal divisions, unresolved legacies of recent conflicts and narco warlord gangs. They are, nonetheless, sovereign states: Tibet lacks even that.

China’s miners find weak states attractive. The Chinese can call the shots, even, if necessary, deploying its own security personnel to protect Chinese assets from local community protesters. The difficulty is in keeping all sides on side, in complex circumstances peculiar to post-traumatic democracies where unresolved basics remain contested. Chinese mining companies, with the active support of the nearest Chinese embassy, must thread a fine line if all contending interests are to be pacified, and extraction can then proceed.

WHAT’S A SOCIAL LICENCE TO MINE?

Only the biggest of China’s miners have the accumulated experience of working in tricky, volatile situations, learning the lessons learned by previous foreign owners of mineral deposits, who sold their asset on to the Chinese when the going got too hot. Biggest, with the most widespread footprint, is Zijin, China’s model national champion for raising the red flag on remote deposits worldwide, and in Tibet.

It was Zijin that in 2014 emerged as the owner of the Shetongmon copper mine west of Shigatse, after Jinchuan smelter in Gansu bought out the Canadian owner, Continental Minerals.[4] Tibetans in Canada suggest Canada’s Continental got a bad deal: they did all the work of proving Shetongmon would be profitable, then under duress they had to sell. But worldwide the mining industry is like that: the smaller companies do all the prep work of proving a deposit has a good business case, then sell to the big guys who have the capital to make it happen. The “majors” quite happily pay a premium price to the “minnows” for having taken all the risks.

For Zijin, this was a sweet deal. China’s party-state extended the Lanzhou-Xining-Gormo-Lhasa railway on to Shigatse, only 50 kms from the Shetongmon mine, and the Jinchuan smelter 2000 kms away in Gansu continued to take the copper concentrate of the mine all the way across the Tibetan Plateau to pour pure metal from the smelter.

Zijin, within China and worldwide, has benefited enormously from official subsidies and capital expenditure on infrastructure, and the political support of state power investing in “development” projects in host countries. Zijin has grown enormously, and now dominates mining in Tibet. Recently, Zijin has bought mines in Argentina, Serbia and Eritrea.[5]

from official subsidies and capital expenditure on infrastructure, and the political support of state power investing in “development” projects in host countries. Zijin has grown enormously, and now dominates mining in Tibet. Recently, Zijin has bought mines in Argentina, Serbia and Eritrea.[5]

Yet in Colombia Zijin faces circumstances quite unlike Tibet. When extracting Tibet’s resource endowment, if local communities protest, the security state is ready and willing to send in the paramilitary and criminalise the protesters. Local government cadre promotion prospects depend on crushing dissent quickly. It says so in their employment contract. In Colombia, however, having the state on side is not enough, you also need a social licence, a concept alien to China’s authoritarian command and control system.

In Buritica, up in the mountains of Colombia, the locals are poor, so poor some eke a living sorting through Zijin’s waste dumps for flecks of gold. Zijin doesn’t like it. In February 2023 Noticias Financieras explained : “Buriticá has a troubled history, formerly being in lands disputed by leftist guerillas and right-wing paramilitaries until about a decade ago. The town is near still-active narcotrafficking routes, and is a regional centre for artisanal, illegal, and legal artisanal mining (not all artisanal mining in Colombia is illegal).”[6]

Zijin’s response to poor locals sifting Zijin’s dumped mines wastes is to criminalise them, as they would in Tibet. But Colombia is a democracy, the protests only get stronger, Zijin is out of its depth. It’s so much simpler in Tibet. There you have entire security state garrisons ready to send in the riot squads to quell the masses.

Even more embarrassing for Zijin is the scrutiny of experienced environmental law compliance monitors from China, working at University of Maryland Law School in Baltimore, who closely watch Zijin’s steep learning curve, as it discovers the inconvenient truth that the world is not like Tibet.

China’s environmentalists who remain inside China have been silenced for the past decade. But some left China, and persist in scrutinising the harm China does in the name of win-win development throughout the developing world. There is no comparable scrutiny of what China does to Tibet.

Gone are the days when China’s miners could enlist the naïve willingness of the NGO Global Witness to certify China’s compliance with conflict minerals standards while exploiting Congo, yet exempting the same corporations from any oversight of their mines in Tibet.

Who will speak up for the conflict minerals/critical minerals China extracts from Tibet? Conflicts persist.

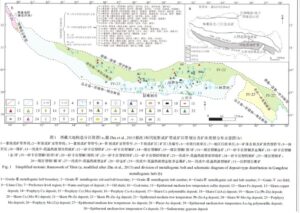

METALLOGENSIS

China sees Tibet as metallogenic-a term much used by geologists- and covets the treasures within. Although metallogenic means giving birth to, there is nothing feminine about China’s discourse about the violent forces that concentrated minerals into deposits, or in the urgent necessity of now thrusting into the earth to extract treasure.

In Tibetan culture, the entire landscape is decidedly feminine, in the shape of a srinmo so vast she animates the landscapes of not only central Tibet but much of Bhutan too. She is not to be messed with. She long predates the Tibetan assimilation of Buddhism, and requires much effort to restrain her powerful energies from generating the earthquakes that can erupt at any moment in a young, rising land still in formation.

Those old Tibetans knew the land was metallogenic, they did mine small quantities of minerals and knew it is best to leave landscapes to the feminine forces that shape them. Lest she restlessly move her arms and legs, she must be weighed down by building temples at her joints, then let be, to give birth to Tibetan civilisation. “Naturally wild and dangerous, when controlled it is just she out of whom civilisation is built.”[7]

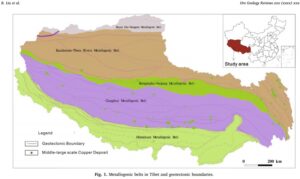

China’s official name for the metallogenic belt of copper/gold/silver/molybdenum deposits that stretches right across U-Tsang, is Gandese, a pinyin mangling of Kang Tise, meaning specifically the holy pilgrimage mountain known worldwide as Kailash.

These days Gangdese signifies a copperbelt that stretches over 1500 kms from the far west of upper Tibet to well past Lhasa to the east. Metallogenic Gandese is a signifier of wealth, of an abundance of minerals just waiting to get out of the ground. Gangdese is fungible, monetizable, a vehicle for wealth creation, the object of copper cupidity, the lust for copper that enables you to become a big shot. It is hard to imagine a bigger change of meaning, as Kang Tise becomes Gangdese: the purifier of minds becomes the corrupter of minds.

[1] Hugh Miller, Simon Dikau, Romain Svartzman, Stéphane Dees, The Stumbling Block in ‘the Race of our Lives’: Transition-critical materials, financial risks and the NGFS Climate Scenarios, London School of Economics Centre for Climate Change Economics, Working Papers 417, 2023, https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/the-stumbling-block-in-the-race-of-our-lives-transition-critical-materials-financial-risks-and-the-ngfs-climate-scenarios/

[2] Nanlai Cao, Constructing China’s Jerusalem: Christians, Power, and Place in Contemporary Wenzhou, Stanford, 2010

[3] Javier Blas, Jack Farchy, The World for Sale: Money, power and the traders who barter the world’s resources, Penguin Random House 2021

[4] Gabriel Lafitte, Spoiling Tibet: China and resource nationalism on the roof of the world, Zed Books, 2013, 160

[5] Andrew Willis, B.C. company’s friendly bid to acquire billion-dollar gold mining project sidelines Chinese shareholder, Globe and Mail, 15 February 2023

[6] Editorial in Noticias Financieras, 14 Feb 2023, The Sad Case of Zijin Mining In Colombia

[7] Janet Gyatso, Down with the demoness: Reflections on a feminine ground in Tibet, in Janice Willis ed., Feminine Ground: Essays on women and Tibet, Snow Lion, 1987, 40