CHINA’S EXTRACTIVISM IDEOLOGY

Blog 1 of 3 on the rapidly accelerating boom in China’s demand for critical minerals

In a decarbonising world transitioning to “green” energy, Tibet is now emerging as China’s frontline source of two key critical minerals: copper and lithium. Both have been exploited by Chinese miners for decades, but in coming decades extraction from Tibetan landscapes is almost certain to intensify.

Tibetan mineral deposits are at the forefront as never before of China’s ambition to retain its role as the world’s factory.. Not only, in China’s eyes, does Tibet have plenty of lithium and copper, China must intensify its extraction from domestic sources it owns and completely controls, in a decoupling world of sanctions, blockades and wars both hot and cold. In an increasingly risky world, de-risking means digging up Tibet’s abundant endowment of critical minerals, especially copper and lithium.

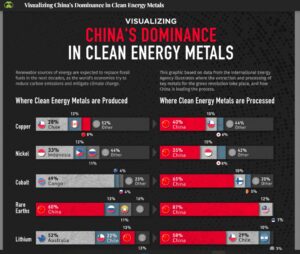

The reason Tibet is now frontline is straightforward: China already dominates the processing of most minerals, and their manufacture into the myriad products that make China the world’s factory. The one aspect of the entire commodity chain that China lacks is onshore ownership and exploitation of the actual mineral deposits. That is where Tibet comes in, as the upstream start of the flow of stuff that enables China to continue its domination.

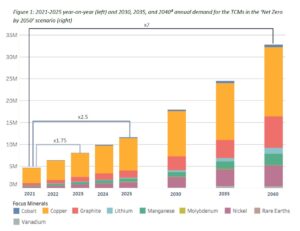

Recent efforts to estimate trends in demand and supply of critical minerals essential for a decarbonising a world (that expects to continue using as much energy as ever) say that by 2040 the world will need 700% of current critical minerals extraction. Copper demand is the biggest factor.[1]

Until now, China has had the luxury of sourcing its copper from Chile, Peru, Zambia, Congo or Tibet, all available for exploitation, for Chinese ownership and for long distance transport to be processed in lowland China.

China has enjoyed the luxury of sourcing its lithium supply from Tibet, Chile or Bolivia. Where to invest in the next big mine has been a question of profitability and efficiency, on the assumption that shipping semi-processed ores thousands of kilometres on oil fuelled ships will always be cheap. That has all changed. All those oil-fuelled ore ships: what is going to fuel them in a decarbonising world? Alternative sources far from China are now more expensive and riskier.

In Chinese eyes, Tibet is metallogenic, giving birth to extractable minerals wherever you look, especially in the long west to east belt of central Tibet, with Lhasa its centre. Metallogenic it may be, but actual extraction requires more: a whole set of causes and conditions has to arise at the right moment. That moment has now arisen.

DESPOILING TIBET, BY ORDER

Until recently the number of large-scale mines in Tibet has remained low, much lower than the number of deposits China’s geologists have explored and labelled as large (or super-large) polymetallic deposits of not only copper but also gold, silver and molybdenum, all of them profitable. There are over 40 such deposits within 200 kms of Lhasa, the geologists say.[2]

That could change soon. The Anthropocene age of acceleration now includes Tibet. At the highest level, the December 2022 Central Economic Work Conference declared: “we should accelerate the construction of a modern industrial system. We will focus on key industrial chains in the manufacturing industry, identify key core technologies and weak links in parts and components, and concentrate high-quality resources on joint efforts to ensure that the industrial system is independently controllable, safe and reliable, and that the national economic cycle is smooth. It will strengthen domestic exploration and development of important energy and mineral resources and increase storage and production, accelerate the planning and construction of a new energy system, and enhance the national strategic material reserve guarantee capacity.” China has joined the rich countries in onshoring its domestic extraction zones, in the name of security, in a world where globalisation is increasingly uncertain.

A COMMAND TO INTENSIFY EXPLOITATION

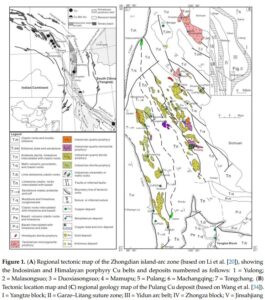

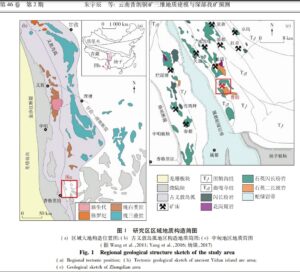

This is not the first time China’s miners, whether state-owned or private, have been instructed to intensify exploitation of Tibet. In 2017 central leaders decreed the construction of several more copper mines in Tibet, not only near Lhasa but also much further east, at Yunnan Pulang, 云南普朗铜矿 yúnnán pǔ lǎng tóng kuàng.

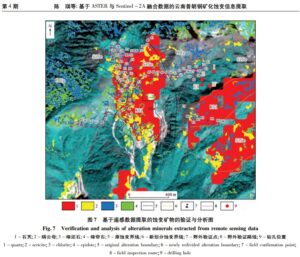

Pulang is not one deposit but many, with many concentrated ores China needs. Chinese geologists have affixed the mine symbol, of crossed hammers, on ten deposits within a 25 kms circle, a bonanza.[3]

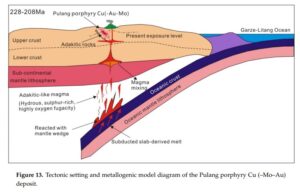

The Dechen Pulang deposit (28° 2′ 19” North , 99° 59′ 23” East, north of Gyelthang and south of Chathreng) is massive, much closer to China’s copper consumption markets, in a province which China historically mined for copper for centuries, close also to the hydro dams needed to power energy-intensive smelting. Officially it is the property of Yunnan Dechen [Diqing] Mining, 云南迪庆有色金属有限公司and also known as Xuejiping Cu deposit, Shangri-La County (Xianggelila Co.; Zhongdian Co.), Dêqên Autonomous Prefecture (Deqin Autonomous Prefecture; Diqing Autonomous Prefecture). It is close to the provincial border dividing Yunnan from Sichuan Kandze.

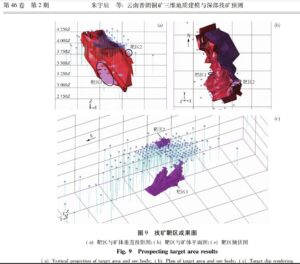

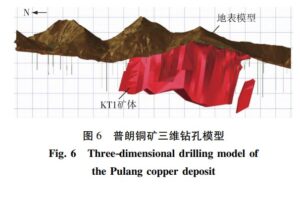

However, it is still at an early stage of extractive design, with a three dimensional mapping of the deposit published in China’s Journal of Geology only in June 2022. The authors say: “Pulang copper deposit is located in the east of Diqing [Dechen] Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in northwest Yunnan. It has been found that the copper amount of the deposit has reached a large scale and has a super large prospect. Through the analysis of the geological background of the Pulang copper deposit and the collection of basic geological data,the three-dimensional visualization modelling technology was used to build the three-dimensional geological model of the Pulang copper mine,determine the favourable ore-controlling elements and build the prospecting prediction model. Through the comprehensive metallogenic prediction of a combination of the weight of evidence method and information method,two prospecting target areas were delineated,which provides reference for next prospecting of the Pulang copper deposit.”[4]

Because this is a big deposit, the extraction enclave will be big and expensive, requiring a mining company with plenty of access to capital, usually meaning other people’s money loaned at the directive of the state, with a long lead time before profits are made.

The copper deposit outcrops at ground level at altitudes of 3860 m to 4020 m, with the underground deposit up to 500 m deeper. Technically the mining could be an open cut pit, but China does not want a giant hole in Shangri-la, marketed heavily as an earthly paradise. The rugged terrain and altitude, and runoff that all flows into the upper Yangtze, all mean the mine must be underground, deploying the block caving method. That means digging a huge cave underneath the deposit, then blasting the crumbly ore-rich rock above, so it collapses into the excavated cave and can then be hauled to the surface. An expensive operation. Risky. Little wonder it is taking many years to plan it all. But the plans are now done, and the result is an operation on a scale that is amazing. Each year 12.5 million tons of ore will be extracted.

ANOTHER GIANT MINER ENTERS TIBET

How to finance such a major investment, all predicated on the copper price remaining as high as in the 2022 boom year? Yunnan Diqing Nonferrous Metals is the owner and mine operator, but is owned by an older mining company with deeper roots in Yunnan copper mining, and deeper pockets due to best connections at a high level, enabling access to concessional funding from state banks. The cadres of Diqing Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture Development Investment Group Co., Ltd hold 3.4% of the shares of this company which trades its shares on the Shenzhen Stock Exchange [000878]. However, in these times of agglomeration and upscaling, Yunnan Copper is merely the copper arm of Chinalco, one of China’s real giants. Chinalco has the muscle to do this.

But it is risky. The entire deposit is almost vertical and friable. The concentrations of copper and other minerals occurred hundreds of millions of years ago, and since then the entire landscape, of what once was a shallow ocean, has been tilted close to vertical by Tibet ploughing into China, with this easternmost edge of the Tibetan Plateau at the forefront.

Although China says the mining will be highly automated, reducing the risks to human life, the process of blasting rock into a man-made cave below is full of risks hard to calculate in advance, in a young landscape prone to earthquakes.

Pulang is 350 kms southeast of the Yulong deposit, near Jomda, between Derge and Chamdo, where a huge mine now well under way. Metallogenic Tibet is fast becoming a whole province of extractivism.

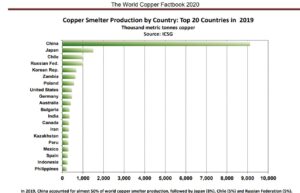

China’s global dominance of copper production, especially the smelting of pure copper metal from ore concentrates hipped to smelters from Tibet, Africa and S America, is further enhanced by the formation of a cartel of China’s smelters and the giant Freeport McMoRan. Meeting in Singapore, at a time when copper smelters were in great demand, they hiked smelting fees by 35%. Nobody baulked. Copper is on a roll. The cartel agreed on a price per pound of $88 and 8.8 cents, a concatenation of eights signifying doubly joyous prosperity, ample proof of China’s dominance. The opening ceremony of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing began on 8/8/08 at 8 minutes and 8 seconds past 8 pm local time.

Freeport McMoRan is a role model for mining Tibet. This Arizona-based corporation’s biggest mine is in the Indonesian province of Papua. Like Tibet, Papua was coercively swallowed by its big, contiguous neighbour, and then colonised. Like Tibet, settler colonisation has been partial and patchy, with control exercised not by immigrant settlers but by the security state. Like Tibet, Papua is remote from the imperial capital, and is very much under the control of the military, and their military industrial enterprises. More on Papua below.

CHINA’S COPPER CUPIDITY

The big profits to be made from exploiting the many major copper deposits of Tibet will not be made by Tibetans, not be generated in Tibet, maybe not even by the smelters, despite their cartel fixing the copper price at the highly fortunate $88.88 per pound of pure metal. The biggest profits are made by financialising copper, arbitraging, leveraging, gambling on future price movements, borrowing other people’s money to gamble, over and over, with actual copper the anchor that lends legitimacy to the global game of commodity trading. This makes Tibetan copper a “play” in a global game.

The mining companies and their smelters know this game, and know they can not only hedge against price swings but multiply their profits dramatically if they are faster, bolder and more cunning than their competitors.

Copper has become the starting point for globalised gambling because, like lithium, nickel, cobalt and rare earths, it is a critical mineral for the decarbonisation era. Critical minerals attract swarms of investors and gamblers because they are now in such demand, supply could lag behind demand, and prices can shoot up.

Human uses for copper are thousands of years old, just think of the Bronze Age of preBuddhist Harappa, Sogdia, Khwarazm, Khorasan, all neighbours of the Tibetans. So copper was not always seen as hot, in the way lithium, cobalt, nickel and rare earths are suddenly big time. Yet copper is just as intensively needed as the others, is spiking in demand as the others. Insiders, such as the International Energy Agency do include copper as a critical mineral. That means special attention , special assistance from governments, special incentives for extraction, for strategic reserves held onshore by wealthy countries for security reasons. These drive the speculators to pile in, magnetising hot money that is always restlessly seeking the next big thing, the next big moment when money makes more money. Copper is hot.

Not good news for Tibet, especially in a world starting to decouple, in which just-in-time global supply chains now seem so yesterday. China, at the highest level, wants more copper sourced domestically. That means Tibet. It means Tibet must transition from being a heavily subsidised cost centre into a profit centre. It means intensification of copper mining, copper concentrating and copper concentrate shipping to distant smelters. It may soon mean smelting copper ores into pure copper metal in Tibet, something that hasn’t happened yet. Until now, the mining and concentrating of copper ore has largely been the business of smelting companies, for whom their mines in Tibet are captive, contractually obliged to sell to the company smelter at prices that concentrate the profit at the smelter.

A further incentive for intensification is that almost all Tibetan copper deposits mapped by China’s geologists also contain gold, silver and molybdenum, all of them profitable as well, all produced as pure metals in the same smelting process, pouring off the smelter as they separate, as molten liquids, according to their atomic weight. Smelting does it all. The amounts of gold and silver may be small, but they are often found at the top of copper deposits, enhancing quick profitability as soon as mining begins. That incentivises investors, who can expect a quick return on investment.

No-one would excavate a huge open cut pit just for the gold and silver, still less an even more expensive underground mine. Copper is the driver. Today’s internal combustion energy car requires around 22 kilograms of copper. Tomorrow’s electric car requires 55 kilos of copper, so the International Energy Agency tells us.

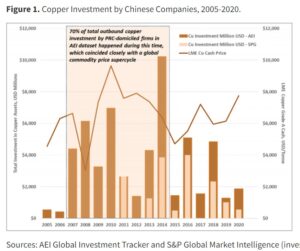

China dominates all phases of copper production and use, from its ownership of major copper mines in Tibet, Chile, Peru, Zambia, Congo and more, to its global shipping of copper concentrate to smelters based in China, to the manufacture of copper-intensive technologies such as power grids, electric cars, wind turbines and solar panels connecting to grids. China also owns the London Metals Exchange, the world’s biggest metals trading platform, and has many financialised game players gambling on future copper prices.

CIVIL-MILITARY-PARTY-STATE FUSION

China’s mining companies, especially those with global reach, mirror the ideological stance of China the party-state.

Integral to China’s pitch to the world is that its rise and rise, unlike other superpowers, is entirely peaceful. China invades no-one, seeks only win-win solutions that benefit all, wherever China invests in the global South.

For China’s mining companies extracting minerals from dozens of countries across the developing world, from Mongolia to Peru, Indonesia to Congo, there is a parallel master narrative. China’s miners respect the locals, benefit everyone, adhere to global standards of good practice and are committed to reducing emissions by embracing green renewable energy in their operations. Model global citizens.

As Chinese corporations gradually learn, often the hard way, to operate globally, they increasingly weave their way into mineral-rich conflict zones, seeking that critical path that enables them to build and operate an extraction enclave, do the initial steps of ore processing locally (including disposal of waste tailings), then ship semi-processed rock many thousands of kilometres by rail, port and ship, all the way to China.

These are complex operations, made much more complex when local stakeholders raise objections to some or all of the project and its impacts. Since, within China, corporations can rely on local cadres to suppress local protests, learning to manage citizen protests, whether in Colombia, Congo or Indonesia, is a steep learning curve.

Sometimes there is a short cut: just get the national government on side and they will do the policing that suppresses local communities. This is far from unique to China and its miners. The world’s biggest mining companies have often been accused of doing deals with sovereign states to suppress objectors. China has learned this lesson from the previous miners who sold to the Chinese, or are in partnership with them. Congo. More on this below.

[1] Hugh Miller, Simon Dikau, Romain Svartzman, Stéphane Dees, The Stumbling Block in ‘the Race of our Lives’: Transition-critical materials, financial risks and the NGFS Climate Scenarios, London School of Economics Centre for Climate Change Economics, Working Papers 417, 2023, https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/the-stumbling-block-in-the-race-of-our-lives-transition-critical-materials-financial-risks-and-the-ngfs-climate-scenarios/

[2] Pan Tang, Ju-xing Tang et al., Mineral chemistry of magmatic and hydrothermal biotites from the Bangpu porphyry Mo (Cu) deposit, Tibet; Ore Geology Reviews 115 (2019) 103122

[3] Zhu Yuchen, Li Qian, Three-dimensional geological modeling and deep prospecting prediction of the Pulang copper deposit in Yunnan Province, 地质学刊Journal of Geology, vol 46 #2 2022, 190-198

[4] Zhu Yuchen, Li Qian, Three-dimensional geological