UNESCO WORLD HERITAGE THREE PARALLEL RIVERS PROTECTED AREA UNDER THREAT

Blog one of three

This 2019 moment uncannily echoes 2004, when Chinese environmentalists and an investigative newspaper revealed Tiger Leaping Gorge, on the southeastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau, was about to be dammed, stilling a mountain river famed for its untamed wildness and spectacular gorge. That 2004 report opened an official secret, that a planned cascade of dams on the Dri Chu (Jinsha 金沙江in Chinese, Yangtze in English) would reach upriver as far as the untouched awesome beauty of Tiger Leaping Gorge.

Environmentalists mobilised support, scientists investigated the technical obstacles. By 2007 their advocacy achieved a result. The state owned dam building corporations backed off, an iconic landscape had been spared. This was a historic win for citizen initiatives.

Fast forward 15 years to 2019. That crusading investigative newspaper, Southern Weekend is long closed by orders from above. Hu Jintao, China’s leader in the first decade of this century is long gone, and officially dismissed as a do-nothing. Xi Jinping is in sole command, and a more muscular new era is proclaimed. Damming of Tiger Leaping Gorge is back, and environmentalists are aghast. So certain these days are arrest, detention, torture and public confession, for publicly questioning official policy, they dare not speak directly. This is their plea.

BACK FROM THE DEAD

At the highest level Tiger Leaping Gorge dam, now rebadged Longpan dam, has been authorised for construction. In 2019, the central planners of the National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, Ministry of Natural Resources, Ministry of Ecology and Environment, Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, People’s Bank and National Energy Board issued a long list of projects to proceed, including many dams on Tibetan rivers, the biggest being Tiger Leaping/Longpan.

Tiger Leaping Gorge is now Longpan 龙盘. The Baidu online encyclopaedia explains why the name change: “In order to avoid public doubts, the Tiger Leaping Gorge Hydropower Station was renamed Longpan Hydropower Station.”

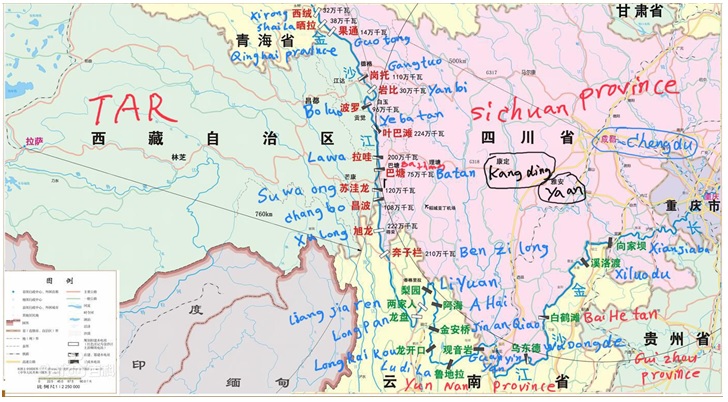

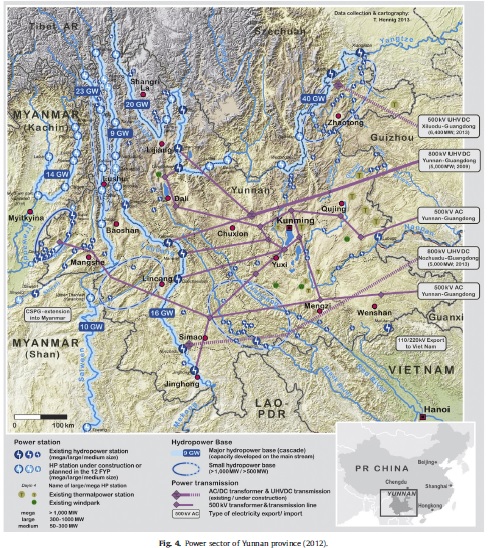

Of the 17 dams on the Jinsha, already built or planned, Tiger Leaping Gorge/ Longpan is planned to generate 4000 megwatts of electricity, a huge amount. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jinsha_River

This is a massive project. Its promoters say the installed capacity of Longpan is 4.2 million kW; the annual power generation is 17.5 billion kWh . Longpan Reservoir will have a storage capacity of 21.5 billion m3. Behind the dam wall, the newly forming lake drowning the farmland of 100,000 villagers, will stretch upriver for 265 kms. When filled, the lake will cover 373 sq kms.[1]

DESTINATION SHANGRI-LA

Distance is vanquished, the ancient kingdoms of Gyalthang and Satham (Lijiang) united by China’s engineering spectaculars.[2] Two oversold, overloaded tourism destinations connected by dams and bridges. The road bridge is due for completion in 2019, the rail bridge later. Because rail lines need gentle gradients, there is a lot more tunnelling required. Tibet is drawn closer to China, more accessible to more people, less remote, more consumable.

Fictional Shangri-la became a defined territory, certified officially as the true location of the 1930s hit novel and movie, Lost Horizon, with the three parallel rivers crucial to turning fiction to fact. “In order to credibly identify Zhongdian as the ‘true Shangrila’, a key task of the expert group was to document similarities between the Diqing (Dechen in Tibetan) area and the setting of Shangri-La in Lost Horizon. For this purpose they read the novel carefully (in several Chinese translations), taking note of geographical features such as the three rivers running through the area, the characteristics of the novel’s Valley of the Blue Moon and the snowcapped mountain towering above. The three rivers of Lost Horizon were easily identified, since the Nu (Chinese: Nujiang), Mekong (Lancang) and Golden Sand (Jinsha) all run through Diqing.”[3]

MEET THAT TIGER BY RAIL, BY EXPRESSWAY, BY SEDAN CHAIR

At its narrowest, the Jinsha is only 25m wide, hence the romantic story that a tiger was seen leaping it. The name makes it wholly Chinese虎跳峡; Hǔ tiào xiá, no longer a remote divide between ethnic minority kingdoms. Being now fully Chinese, it is being bridged, its waters tamed by diversion aqueducts and dams, and the narrowest point for a leaping tiger is also the narrowest point for engineers to span a wall across the river.

The narrower the river the more it rages in tumult, especially in the summer monsoon season. From the glass bottomed viewing platform, where rich tourists are carried down by sedan chair 轎 coolies轎夫,

nature in its wildness is close, yet at a safe distance. The Dri Chu/Jinsha is narrowed by mountains on both sides. On the Tibetan (northwest) side, the engineers decided the metamorphic marble and crystalline schist rock was strong enough to anchor the suspension cables directly into the rock, requiring excavation of tunnels for the expressway lanes to plunge into Haba Gangri (Haba Snow Mountain哈巴雪山 Hābā Xǔeshān), plus tunnels directly above to hold the cables.

On the other side, in Lijiang Naxi Autonomous County, the slope is not quite so steep, making it possible to erect massive concrete pylons to hold up the cables, a more conventional kind of suspension.

The bank on the Lijiang side, the Dri Chu’s right bank, is seriously unstable, having been pushed up by the tectonic advance of the Tibetan Plateau, resulting in many fractures. The entire right bank is so loose that many Chinese scientists have wondered whether it can hold, if the Tiger Leaping Gorge/Longpan hydro dam is built. There has been serious investigation of the likelihood of a massive landslide collapse of the right bank, lubricated by the impounding of water behind a dam wall 276 metres high.[4]

UNESCO PROTESTS

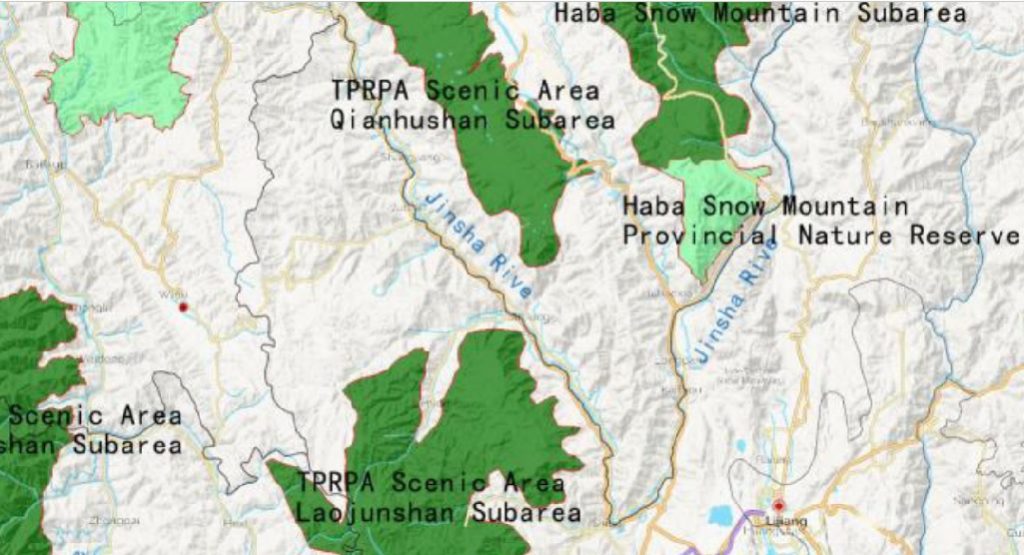

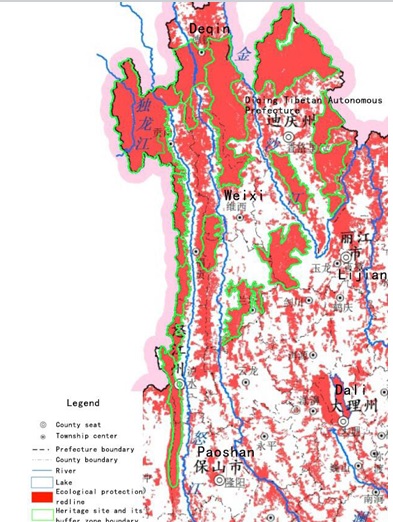

Given the cumulative impact of water diversion aqueducts, hydro dams, displaced populations, tourism infrastructure, road expressway and high speed rail bridges, UNESCO has responded, in 2017 expressing alarm: “Pressure on the property primarily stems from infrastructure development. Spatially separating conservation and development is not, in and of itself, an effective strategy to ‘harmonize the coexistence and relationship between development and the nature’, as the State Party puts it in one of its fundamental objectives. The highly significant modification of the river systems, which gave the property its name, amounts to a profound landscape change, with additional threats from large-scale water diversion programmes. While the projects may be located outside of the “commitment area”, the effects of disturbance, loss of connectivity, improved road access facilitating illicit activities and species invasions inevitably accompany large infrastructure projects beyond their spatial footprint. Besides, there are linkages between freshwater biodiversity and processes affected by dams and terrestrial ecosystems. Although located outside the property, the massive hydropower projects and the associated infrastructure objectively change the natural beauty and aesthetic importance of the valleys and their numerous important views, which contribute to the property’s OUV (outstanding universal value) under criterion (vii), and cannot be restricted to selected elements of a landscape. Therefore, the visual impact of these infrastructure projects is considered to exert a direct negative impact on the OUV.” https://whc.unesco.org/archive/2017/whc17-41com-7B-en.pdf State of conservation of properties inscribed on the World Heritage List

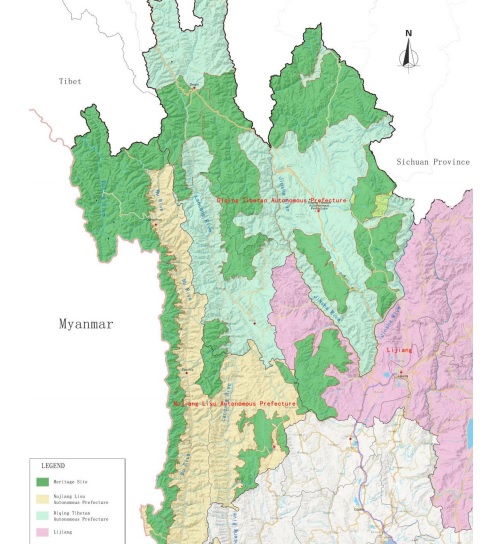

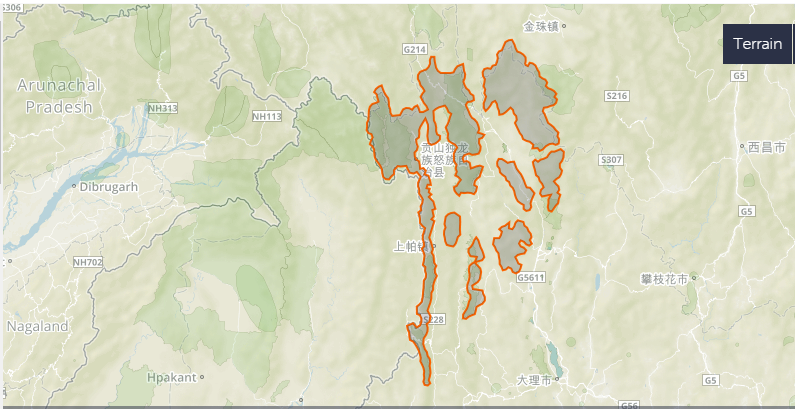

However, separating conservation and development is China’s strategy, supported by a zoning system that makes all territory either economic or ecological. This rigid separation is acute in the UNESCO Three Parallel Rivers World Heritage site, where China, from the beginning of the nomination process, excluded the actual rivers from the protected area, including only fragmented steep valley landscapes and peaks, between the three rivers.

This is a nonsense, and UNESCO let China succeed, while knowing the dam plans had accumulated for decades, awaiting construction. A landscape is a landscape, especially where mountain rivers incise deep valleys and microclimates conducive to the abundance of medicinal herbs found on the steep slopes above the three parallel riverbeds, precious to Tibetan and Chinese traditional medicine alike. “The topographic variation in this area is remarkable. Elevations can change 4,000 meters within a span of ten kilometres. Subtropical ecosystems exist along canyon bottoms, whereas a few hours’ hike uphill brings one to temperate, boreal, and arctic-alpine life zones. Along the banks of these rivers and in the nearby mountain valleys grow more than ten thousand different plant species, making this region one of the most biodiverse in the world.”[5]

China’s partitioning of the valleys and gorges from the rivers is instructive: the valleys are too steep for farming or other economic purposes, and are thus classified as waste land suited to World Heritage status; whereas the rivers rushing the gorges are economic, primarily for their hydropower, flood control and water diversion potential, long measured and assessed by Chinese engineers. A further reason the Dri Chu/Jinsha is an economic asset is that dams slow the river, leading to deposition of sediment behind dam walls, thus relieving the Three Gorges Dam, farther down the Jinsha/Yangtze, of the threat of silting up.

However, sedimentation is double-edged. The sharp turn of the Dri Chu/Jinsha is where the three rivers, all running from NNW to SSE, cease to be parallel. Suddenly the Jinsha changes course, heading NNE, making a sharp left turn where it also slows sufficiently for much sediment to settle out of the stream flow and raise the river bed. That unconsolidated sediment is in places 250 metres thick, yet the Longpan dam is to sit atop it, a hazard unfamiliar to dam builders.[6] UNESCO considers itself an expert on hydro dam sedimentation, and is holding an International Water Conference 13 and 14 May 2019 at its Paris headquarters, immediately prior to the World Hydropower Congress, also in Paris. This could be a suitable moment to ask UNESCO if it agrees with Chinese researchers who say at Tiger Leaping Gorge “it is difficult to construct a high dam large reservoir on a deep overburden.”[7]

The dam is a massive project, which China’s hydraulic elite call comparable to the Three Gorges Dam much further down the Yangtze. From an engineering perspective Three Gorges and Tiger Leaping Gorge are one single interconnecting hydraulic civilisation system, including the other 17 dams in between, with Tiger Leaping/Longpan at the crown. This is why the dam builders are so persistent in pressing for it to be built.

CHINA’S RESPONSE TO UNESCO

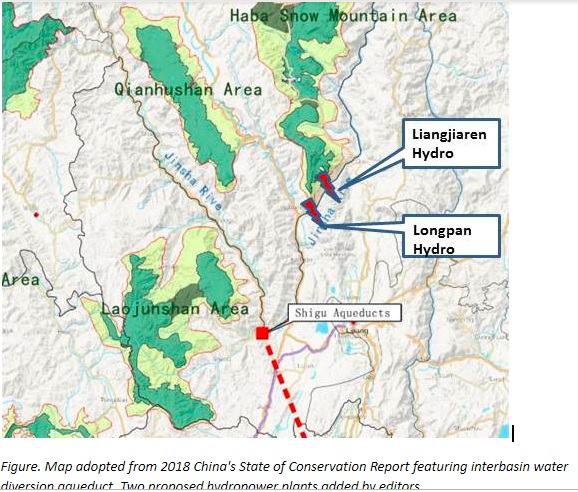

UNESCO concedes it lacks any jurisdiction over areas outside the scattered jigsaw pieces under its protection, yet expresses its concern at “projects located outside of the ‘commitment area’”. In response, in late 2018, China issued a bland State of Conservation report referring vaguely to the prospect of even more dams: “One hydropower development project, so called one reservoir with eight cascades, along Jinsha River midstream has accomplished constructions of Liyuan, Ahai, Jiananqiao, Longkaikou, Ludila and Guanyinyan power stations. Two of planned stations, Longpan power station and Liangjiaren power stations, the Ministry of Environmental Protection states, as the aspects of ecological and environmental protection, Longpan power station and Liangjiaren power stations need to be further studied before making any decisions. The relevant construction plans and EIAs have not been completed, reported and ratified. And they are not under construction”. 2018 State of Conservation report by the State Party: http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1083/documents

UNESCO is again humiliated. Environmentalists in China are horrified to see the steady progression of the Longpan 6000 megawatt dam through the official approval process, as part of “green development”, along with investments in wind power and solar power, listed as a priority for construction.

How did this unpopular dam make a decisive comeback? That’s

the story told in blog two in this series.

[1] An Shenyi, 安申义 Comprehensive Benefits of Longpan Hydropower Station in the Main Stream of the Yangtze River, China Hydropower Engineering Society, 13 Nov 2014

http://www.hydropower.org.cn/showNewsDetail.asp?nsId=14779

[2] Gyalthang (rGyal thang) is located in the easternmost foothills of the Himalaya Mountains in the northwest corner of present-day Yunnan Province in southern Kham. From 1725 until 2001, this area was referred to as Zhongdian 中甸 in Chinese, but in 2001 Zhongdian County was renamed Shangri-la County (Xianggelila xian 香格里拉县).

[3] Åshild Kolås (2017) Truth and Indigenous Cosmopolitics in Shangrila, The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology, 18:1, 36-53,

[4] Wang M Y, et al,.A seismic study of the deformable body on the Longpan right bank of the Jinsha River .Chinese Journal of Geophysics, 2006, 49(5):1489~ 1498

XU Wen-jie 徐文杰 et al, 虎跳峡龙蟠右岸边坡稳定性的数值模拟 Numerical simulation on stability of right bank slope of Longpan in Tiger-Leaping gorge area, 岩土工程学报, Chinese Journal of Geotechnical Engineering 2006 #11

JIANG Shu et al, Long-term kinematics and mechanism of a deep-seated slow-moving debris slide near Wudongde hydropower station in Southwest China, Journal of Mountain Science, 2018, 15(2): 364-379

[5] Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen The History Of Gyalthang Under Chinese Rule: Memory, Identity, And Contested Control In A Tibetan Region Of Northwest Yunnan, PhD dissertation, North Carolina, 2016, 2

[6]王启国/ Qi-Guo Wang, Causes of Riverbed Deep Sedimentation and Engineering Significance of Tiger Leaping Gorge Reach of Jinsha River, Chinese Journal Of Rock Mechanics And Engineering. Vol. 28 Issue 7, p1455-1466

[7]王启国/ Qi-Guo Wang, Causes of Riverbed Deep Sedimentation and Engineering Significance of Tiger Leaping Gorge Reach of Jinsha River, Chinese Journal Of Rock Mechanics And Engineering. Vol. 28 Issue 7, p1455-1466