Blog 1 of 3 on a big new hydro dam in Tibet

RED GENE PRINCELINGS MAKING TIBET CHINA’S

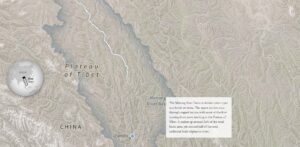

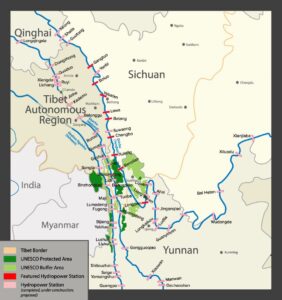

In May 2023 the first big new hydro dam in several years in Tibet was announced. It will not be on the Yarlung Tsangpo but the Za Chu, the uppermost Mekong.

The announcement came not as official media propaganda, but in the form of a Huaneng corporate filing with Shanghai Stock Exchange to advise investors in the company.

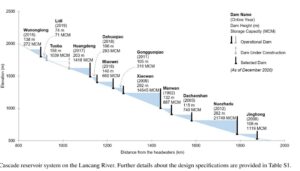

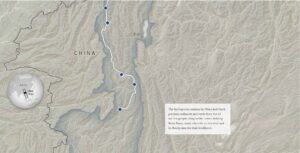

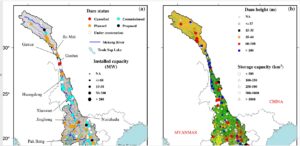

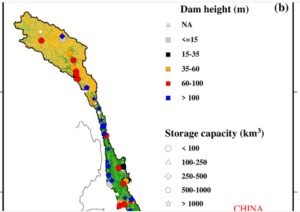

Despite being heavily invested in coal fired power plants with limited futures, Huaneng remains one of the big five state-owned power corporations that electrify the world’s factory. China is planning its extra power supplies for the mid 2030s, and Huaneng will deliver, from Tibet. For the first time ever, China’s Huaneng is building a big hydro dam on the Za Chu/Mekong/Lancang Jiang, in Tibet, near Markham. This location is way further upriver than the many Chinese dams on the Mekong that so distress the downstream communities. This bold shift up into Tibet Autonomous Region now directly impacts the farmers and fisherfolk way down, in Cambodia, Vietnam, Thailand, Laos and Myanmar.

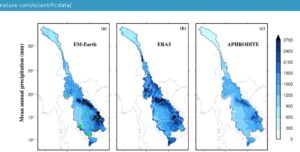

The installed electricity generating capacity will be 2.6 million kilowatts. Actual output in kilowatt hours of produced electricity is planned to be 11.3 billion kwh. That projection assumes no major climate change between now and 2034, even though rainfall is highly dependent on the monsoon, and recent years have been highly variable. This one dam will instal turbines capable of generating more electricity than the entire cascade of four dams on the Yarlung Tsangpo at Lhoka Zangmu. But is this dam a standalone?

China’s infrastructure-building state-owned corporate giants create their own realities. In this hall of mirrors Huaneng stands tall.

Huaneng’s sticker price is RMB 58 billion, $8.2 billion, with a construction period of 132 months, a long wait for patient investors before any returns. Since the party-state is the majority owner, that doesn’t matter. That price is likely to rise, both due to logistics problems and the seismic danger.

Huaneng is an old hand in creeping price rises: “In 2019, Huaneng approved the extension of its upper Lancang cascade (10 GW), which will serve China’s Southern Grid, especially the Pearl River Delta. The construction costs per MW will be rather high (about double those of Yunnan’s Xiaowan). The calculated power tariff for UHVDC exported from Tibet to Guangdong is also more than a third higher than exports from Yunnan—not surprising given the greater distances and challenging topography. This is higher than Guangdong’s nuclear power tariffs, but cost-competitive with other alternatives like gas and offshore wind. Higher tariffs mean developers will potentially recover their costs more quickly, and that electricity exports to Guangdong will play a relatively more significant role in Yunnan’s provincial GDP figures, given royalty payments.”[1]

Capitalist Guangdong is far from Tibet, but China’s ultra-high voltage power grids can span the 2000 kms gap, by relying on massive transformers made in Europe, to convert AC electricity to DC for long distance transmission with no loss en route.

TIBET: EXPORT POWERHOUSE

Here is how Huaneng Lancang corporation defines itself on its web landing page: “Lancang River Company is a large hydropower enterprise controlled and managed by Huaneng Group, and is the core and leading enterprise in cultivating Yunnan’s hydropower pillar industry and implementing the “west-east” and “cloud-export” projects, as well as a major player in the “outward transmission of electricity from Tibet”. It is also a major player in the “Tibetan power transmission”. It is mainly engaged in the development, operation and integration of hydropower resources in the Lancang River basin and surrounding areas. It has rich experience in the construction of large-scale hydropower projects and the operation and management of large-scale hydropower plant clusters, and is committed to implementing the “going out” strategy and participating in the development of clean energy in neighbouring countries.”

Guangdong and Hong Kong are far from Beijing, far also from the heavy hand of central leaders who politicise everything. Guangdong pioneered a neoliberal capitalism model that limits the state, and its many predatory ministries all demanding a cut, in order to issue permits for industry to proceed. State capitalism has its limits in Guangdong.[2] Yet only state capitalism, including Huaneng, would invest billions in a dam in Tibet that will not start generating electricity and revenue until 2034.

Huaneng’s announcement of its new dam in Tibet (Autonomous Region) came six days after central leaders issued a new “National Water Network Construction Plan Outline“. This was announced jointly by the CCP Central Committee and the State Council, by both arms of the party-state.

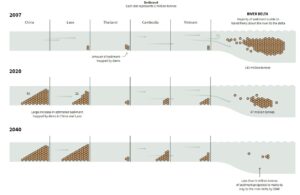

As China works its way higher up the Za Chu/Mekong the river’s waters find it harder to make it down to the basin of the Mekong, where entire civilisations, including the Khmer Empire and Ayutthaya Kingdom were built around the seasonal pulses of the Mekong.

The more the Mekong is locked into a cascade, the top of one dam wall positioned at the altitude of the bottom of the next dam upriver, the more a mountain river is lockstep stilled. The seasonal overflow into a fish-filled inland Tonle Sap lake no longer sustains the fisherfolk. China’s hydro dams fill up with sediment much needed downriver to fertilise the soil.

China ladders its way up into Tibet, displacing not only Tibetan villagers but below, millions of river people in the sprawling lowlands. [3]

China’s greedy grab seals the fate of the Za Chu/Lancang/Mekong. Similar dam building booms are under way close by, on the upper Dri Chu/Yangtze, near Batang, where the river demarcates Tibet Autonomous region from Sichuan province.

China’s hegemony means the human populations, from Tibet, through Yunnan, Lao, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam are silenced, by repressive governments, the entire watershed now within China’s sphere of influence, all encompassed by the belt and road.

Local communities throughout the lower Mekong are distraught, but powerless to do anything about the many dams upriver that China, patron of the client states of the Mekong Basin, has already built. What of this latest burst of dam construction, coming after a lull in which it seemed possible China was losing interest in expensive, unreliable mega dams?

Local communities throughout the lower Mekong are distraught, but powerless to do anything about the many dams upriver that China, patron of the client states of the Mekong Basin, has already built. What of this latest burst of dam construction, coming after a lull in which it seemed possible China was losing interest in expensive, unreliable mega dams?

CONCRETING UP

Huaneng’s own promotional video makes clear its global ambitions, and embrace of energy in whatever form: hydro, coal, wind, nuclear and solar. Huaneng does the lot. But 85% of the energy it produces is by burning coal.

Huaneng has recovered from its near-death experience only a few years ago. Although Huaneng has been dangerously overleveraged, in danger of not only owning stranded assets but itself becoming a stranded asset unable to pay debts, Huaneng has always had the support of the party-state, as guarantor ensuring it not only pulls through but can spin off subsidiaries that are floated on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, to recapitalise what in a wholly capitalist market economy would be risky investments.

One of Huaneng’s strategies, with coal fired power facing an increasingly difficult future, is to renew its hydro dam construction, moving upriver on the Lancang (Mekong, in Tibetan Za Chu) up beyond Yunnan province and into eastern Tibet.

The further upriver Huaneng goes, the more rugged the landscape, the steeper the valleys, the greater the distance the power grid must transmit the electricity, since by design it is destined for the distant industrial hub of Guangdong. Huaneng’s latest dam, in Tibet, is for electricity export, fulfilling the basic demand of all colonisers, that colonies pay for their colonisation or even turn a profit.

ALL IN THE FAMILY

Huaneng’s 2023 announcement reminds us this is a big dam, which will cost a lot and take as long as 11 years to become operational. Mega dams seem to run in the Li family, the family of Li Peng, patron of the Three Gorges Dam. Li Peng is remembered worldwide for ordering the Tiananmen massacre, but he was determined to be forever famous in China as the visionary behind the Three Gorges; and in so doing he established a dynasty. “Huaneng International Power Development Corporation, was headed (1999–2008) by Li Xiaopeng (son of China’s former Premier Li Peng). When in 2012, Li Xiaopeng was appointed as the Vice-Governor of Shanxi Province, his sister, Li Xiaolin (the chief executive of China Power International Development Company from 2004–2015), became a lead figure in Yunnan’s power generation sector. For many years the Li family, rather than the Ministry of Water Resources, or the Yunnan provincial government, decided whether to build a dam on the Lancang.”[4]

Li is a very common family name in China, but there are just so many Lis in high positions in Huaneng in 2023, according to the quarterly Taiwan Economic Journal analysis. Li Jian Pian, Li Xi De, Li Qing Hua are all directors of Huaneng, Li Shuang You is vice chairman, Li Hai Qing and Li Fu Qing are classified as major stockholders, and Li Weidong is chairman of China Huaneng Group Clean Energy Research Institute, which invests in greenwashing carbon capture in Queensland.

As a big-league player, Huaneng is adept at the infrastructure costing game, in which the sticker price creeps steadily upwards once construction has irrevocably started, all extra costs financed by further capital loaned by state owned policy banks instructed to assist, and/or by pricing the electricity sold to Guangdong much higher than closer power supplies. Guangdong is a very long way from the main coal fired belt of Shanxi and Inner Mongolia, and not too far from Yunnan, where there are no longer many dam sites still undammed. The power grids are built, next is the dams. Many more to come, not only this TAR dam, but near Batang, on the Dri Chu/Yangtze, even higher up on the three parallel rivers.

Family businesses rule in Guangdong.[5] Those family businesses expect to continue growing, and to need a lot more power. The Beijing-based Li family business -Huaneng- is all set to power Guangdong from Tibet. The distance in between is 2000 kms.

Huaneng Lancang River Hydropower Inc. is based in Yunnan Kunming, where it has built several of the dams that so vex the Mekong countries downstream. Two Huaneng dams in Yunnan are in the Tibetan prefecture of Dechen/Diqing, which means the Markham dam is not China’s first in Tibet, it is the third.

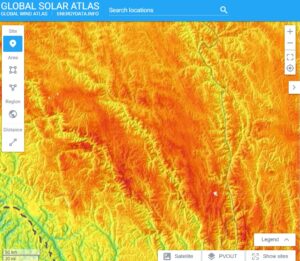

But the Markham dam is different. It requires much more land, due to the bundle of energy sources surrounding the dam, and displaces more people. This new dam is part of a Huaneng package, feeding lots of solar and windpower into the same power grid.

China, after a lapse of interest in mega dams, has rediscovered hydro, and investment advisers are confident Huaneng Lancang River Hydropower Inc. can maintain a fast annual growth rate. The leap upriver into central Tibet is by a corporation with a workforce of 3760, and years of experience wrestling the Lancang/Mekong into submission.

Core investors from state owned policy banks awaiting a rate of return have no choice but to be patient, knowing Huaneng deploys its top-level princeling political connections to get premium prices for the electricity it generates. But there are other smaller investors, lured by Huaneng floating its Mekong hydropower subsidiary on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, who need to be assured it will all work out. This makes for more corporate disclosure than in the past.

Stock exchange rules require Huaneng to specify risks, and the corporate strategy to mitigate them. These due diligence disclosures show a coal-fired giant pivoting to the new era of “green” energy, offering a Tibet package, all interconnected, of wind power, solar power and hydro power. A one-stop shop.

EASTERN TIBET WITH THE LOT: SUN, WIND, RIVERS

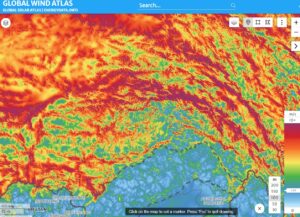

There are not many landscapes in China capable of providing all three energy sources, with not only intense sunshine, strong winds and powerful mountain rivers that seldom occur together, but also the amount of land required. The World Bank’s wind and solar atlases map the intensity of available, extractable wind and solar energy. While water and wind are concentrated in the deep river valleys, solar energy pours into the pastures above, prime grazing land for Tibetan drokpa pastoralists, who since 2018 have been removed en masse, to be displaced by solar farms and power grids. None of this is mentioned in Huaneng’s reporting to Shanghai Stock Exchange. Colonisation of the lands of customary guardians is nowhere mentioned.

When Huaneng Lancangjiang acquires productive landscapes, it continues to grow crops and run livestock on those portions not in use for energy extraction. Former land holders who do remain despite losing land tenure to the corporate giant may be employed as herders.

YOU NAME IT

Huaneng Lancangjiang’s corporate list of the dam properties it has built is long, and includes the biggest dams on the Mekong:

“Manwan Hydropower Station, Lincang City, Yunnan Province

Jinghong Hydropower Station, Xishuangbanna Prefecture, Yunnan Province

Xiaowan Hydropower Station, The border of Nanjian County and Fengqing County, Yunnan Province

Nuozhadu Hydropower Station, Pu’er City, Yunnan Province

Gongguoqiao Hydropower Station, Dali Prefecture, Yunnan Province

Miaowei Hydropower Station, Dali Prefecture, Yunnan Province

Dahuaqiao Hydropower Station, Nujiang Prefecture, Yunnan Province

Huangdong Hydropower Station, Nujiang Prefecture, Yunnan Province

“Lidi Hydropower Station, Diqing [Dechen] Prefecture, Yunnan Province

“Wulonglong Hydropower Station, Diqing [Dechen] Prefecture, Yunnan Province

“Longkou Hydropower Co., Dali Prefecture, Yunnan Province

Ruili River Level 1 Hydropower Co., Shan State, Northern Myanmar

Sanghe Second Stage Hydropower Station, Stung Treng Province, Cambodia

Shilin Photovoltaic Power Generation Co., Kunming City, Yunnan Province

Xucun Hydropower Station, Dali Prefecture, Yunnan Province

Nangohe Hydropower Station, Xishuangbanna Prefecture, Yunnan Province

Lao Wang Zhuang Hydropower Station, Nujiang Prefecture, Yunnan Province

Fengdian River Secondary Hydropower Station, Nujiang Prefecture, Yunnan Province

Niubangou Hydropower Station, Zhaotong City, Yunnan Province

Baihe factory wind farm, Dali Prefecture, Yunnan Province

Yangjiafang Wind Farm, Dali Prefecture, Yunnan Province

Wildcat Mountain Wind Farm, Dali Prefecture, Yunnan Province”

Huaneng also runs the electricity industry in central Tibet, through its Lhasa-based subsidiary Tibet Power Generation.

EXTRACTING RIVER POWER DISEMPOWERS TIBETAN COMMUNITIES

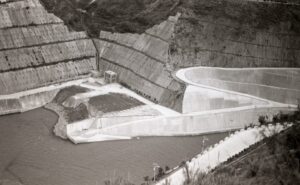

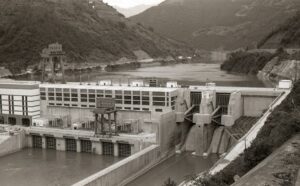

This long list of Huaneng projects on the Za Chu/Lancang/Mekong is an opportunity to foresee what is now likely further upriver. Thanks to a courageous photographer, Scott Ezell, we have photos of these Tibetan villages being overrun by green colonialisation. Even better, Ezell witnessed the start of the damming boom in 2011, then went back in 2019 to see the dams completed.

Ezell tells us what he saw: “Villages along the river were being evacuated, with local people forcibly resettled to long blocks of concrete barracks antithetical to the organic organization and architecture of traditional villages.”

In 2022 Ezell published a book about his Tibetan travels: “Over the next fourteen years I returned a dozen times to Tibet and southwest China. I witnessed transformations so shocking that I felt I was taking blows to my own bones. Massive dam systems killed rivers and displaced communities; mountains were raked apart to provide gravel for construction projects. This narrative journey “to the end of the empire” serves as a microcosm in which the terms of contemporary life stand in stark relief against the vast, raw landscapes of Tibet.

“At the edge of the road an old man stood twirling a prayer wheel and looking down at a metal scaffolding extending across the river. His face was both smooth and wrinkled and reminded me of Edward Curtis photos of American Indian chiefs. Men down below worked with picks, hacking into the stone of the riverbank. A matrix of rebar f!ashed with welding flares, sectioning the space between the banks. Across the river cement trucks drove in to deliver their loads. “What’s going on down there?” I asked the man.

He looked at me, then back down, and said, “They’re building a dam. It will go all the way to the top of the gorge. Everything here will be flooded.”

“But what will happen to you?”

“We were born here. But we will have to go. We don’t know where, but they will take us away, to a relocation settlement somewhere. It will happen soon….”

“They don’t tell us any details,” he said. “They say there will be work — a factory to make something, we don’t know what. Living here we didn’t have to have jobs, didn’t report to anyone; we have always been self-sufficient. Now we will have to follow a production schedule, write our hours on a piece of paper, take orders from a boss and hope our pay checks come on time.” He adjusted a string of bodhi seeds wrapped around his wrist, a Buddhist rosary, and his lips mouthed om mani padme hum. “You see the girls here, hauling stones — the stones are for the dam. They will be crushed into gravel and mixed with cement. We are gathering the stones they are using to displace us. It’s not easy to live here, but we survived. The chorten will go underwater too,” he said, pointing at the shrine.

“But why are they building the dam here?”

“For power. They want more electricity to send to Chengdu. Maybe they don’t have any rivers left to dam there.””[6]

TIBET: THE ONE-STOP SHOP

Little wonder investors are attracted. Yet actual electricity output from these dams has often failed to meet projections, due to climate variabilities which are now intensifying. How to knit these assets together, to deliver electricity afar, reliably, even when the wind isn’t blowing or the rivers in full flow? How to find major industrial customers nearby, in Tibet?

The energy intensity of extraction and transmission of these variable energies is not mentioned.

All of which, Huaneng reports, will do wonders for Tibet: “Promoting economic and social development in Tibet. The construction of this project can stimulate the economic and social development of the Tibet region and transform resource advantages into economic advantages. The construction will stimulate employment growth in Tibet through various means, and promote the development of science, education, culture and health in surrounding areas.”

That standard win-win rhetoric is predicated on assuming what is good for Huaneng and Guangdong is automatically good for Tibet and Tibetans. Does this mean there is dialogue between dam builders and those displaced? No.

WILL TIBET NEED MORE ELECTRICITY?

However, there may in the near future be industries in Tibet, in the same prefecture as the new dam, urgently needs more electricity for the intensification of copper mining and smelting of metals, at Yulong, still further north.

China has big plans for Yulong copper deposit high in the mountains, in Jomda. Of the dozens of “super-large” deposits Chinese geologists have classified, across Tibet., the biggest polymetallic copper, gold, silver and molybdenum deposit of them all is Yulong. Yet the major constraint on upscaling extraction from Yulong is the absence of an on-site smelter capable of pouring off the four profitable metals, enabling dumping the remaining 97% of extracted rock at a dump at the mine. Currently the Yulong operation, run by Zijin, needs energy to blast the mountain, dig out the rock, crush it to powder and cook it in sulphuric acid to produce a concentrate that is about 23% copper, together with the gold, silver and moly. That is still far short of producing pure metals. The concentrate is then taken, by truck and train, to a distant smelter; an energy-intensive long haul, an inauspicious origin for giving the world a post-energy-intensive future.

Even when the Chengdu-Nyingtri-Lhasa railway is built, the nearest railhead will be hundreds of kilometres away. That means hauling copper concentrate that is at least three-quarters waste, millions of tons of it, to a remote smelter. Adding an electrified onsite smelter would mean trucking out only pure metals, leaving 97% of extracted and pulverised rock behind, a long-term legacy laden with toxic metals of no profitable interest in the tailings. Only a big hydro dam could provide sufficient electricity, yet another win-win, in which Tibet is left the wastes long after the mine has come and gone.

Since Huaneng’s new dam/solar/wind complex in Markham may be capable of powering the Yulong copper mine and chemical concentrator, eastern Tibet could become the source of not only electricity but also the copper required to interconnect all the power generator sites, and transmit all the way to Guangdong.

This is the “green” future, much more electrified, much more intensively dependent on copper.

MARKHAM

Despite Huaneng’s most recent filing, the precise location of this energy complex is unspecified in Huaneng’s regulatory filings and subsequent media coverage. Is this because the location is so remote, and no investor needs to know? Is it careless colonialism? Curious, since a shareholders meeting is needed to formally approve the go-ahead by this listed subsidiary of the giant Huaneng.

Almost certainly Huaneng’s latest dam on the Za Chu/Mekong is in Markham. It is likely to replicate Huaneng’s dam building model further down the Mekong, in the Tibetan prefecture of Dechen, in Yunnan. Because these dams so distress the villagers of the six downriver countries, we do have lots of information available, not only from eyewitness Scott Ezell, dodging Chinese checkpoints on his motorbike. We have Brian Eyler, also an eyewitness interviewing Tibetan farmers -wine grape growers- in the Yunnan hills, which became his 2019 book Last Days of the Mighty Mekong.[7] These days Eyler runs a monitoring program that lets Mekong Basin farmers know, in all basin languages, what is happening upriver, hosted by the Washington-based Stimson Centre think tank. Every two weeks a new readout on exactly what is happening to river flow, at all the upper dams, as the seasons cycle.

Eyler’s summing up is stark: “In the case of the upper Mekong, original plans for 9 dams producing 15 gigawatts of power more than 20 dams producing 30 gigawatts. By 2015, Yunnan’s installed hydropower capacity reached 50 gigawatts., enough power to light up 5 cities, each with populations around 10 million. To provide a comparison, the United States, which now ranks second to China in hydropower generation has an installed capacity of 100 gigawatts. Yunnan and surrounding Sichuan and Tibet are currently each slated for 100 gigawatts of hydropower. Before the last dam is built, upward of 8 million residents of these remote river valleys, most of them ethnic peoples, will be forced to relocate to lowland settlements far from their upland homes.”[8]

[1] Thomas Hennig and Darrin Magee, The Water-Energy Nexus of Southwest China’s Rapid Hydropower Development: Challenges and Trade-Offs in the Interaction Between Hydropower Generation and Utilisation 36, in Jean-François Rousseau, Sabrina Habich-Sobiegalla eds, The Political Economy of Hydropower in Southwest China and Beyond, Palgrave Macmillan, 2021

[2] Margaret M. Pearson, Meg Rithmire, Kellee S. Tsai, The State and Capitalism In China, Cambridge 2023, 22

[3] Brian Eyler, Last Days of the Mighty Mekong, Zed Books, 2019

[4] Suzanne Ogden (2022): The Impact of China’s Dams on the Mekong River Basin: Governance, Sustainable Development, and the Energy-Water Nexus, Journal of Contemporary China

[5] Jian-Kun Liu and Yun-Liang Zhang, How are family businesses involved in the organizational network of the Communist Party of China: the perspective of organizational sociology, Chinese Sociological Review, December 2022

[6] Scott Ezell, Journey to the End of the Empire: On the Road in Eastern Tibet, Camphor Press, 2022, 48-49

[7] Zed Books

[8] Brian Eyler, Last Days of the Mighty Mekong, 48-9