What to expect in 2023: A series of blogs about the short term future of Tibet

Blog 1: lithium mania

Never has Tibet been so hot, so desirable. A whole Tibetan landscape was up for auction online in May 2022, and for five days and nights the bids poured in, drawn by what lies under these snow covered hills of Kham Nyagchu in eastern Tibet. JD.com usually auctions jade, jewellery ceramics, porcelain, calligraphy, painting and seal carving, luxury bags, watches, smart phones and computers. This auction was different. What was on the block was mining rights held by a company that had gone broke while searching Tibet for deposits of one of the world’s most plentiful elements: lithium.[1]

The bankrupt exploration company Yajiang Snow Way 雅江县斯诺威矿业发展有限公司 [Sinuwei] had done some drilling for rock lithium in Nyagchu (Yajiang in Chinese) and come up with promising numbers, but that was a few years ago when a lithium boom was a tantalising prospect that was slow to materialise. In fact Yajiang Snow Way was in debt, and anyone who bought it out, for the mining rights, would also have to take on that outstanding unpaid debt.

None of this deterred the bidders. Bidding began at RMB 3.35 million, a modest start for an entire landscape, but understandable given the substantial burden of RMB 1.6 billion in debt a new owner would inherit. By the time the auction concluded five days later, the 21 serious bidders bid against each other 3448 times, driving the price up to RMB 2 billion, almost 600 times higher than the opening bid, and the winner became the 54% owner of a slab of Kham.

The story doesn’t end there. One of the serious bidders was CATL, a major lithium battery manufacturer. Having lost out in the open auction, CATL then quietly closed a deal with the new owner, buying it out for three times as much again, bringing the total price to RMB 6.4 billion. Just type Dechenonba into a search engine.

Nor is this story of greed for Tibet’s mineral endowment unique. Six months later, in November 2022, a maker of exquisite luxury jewellery based in distant Shenyang, put in the highest offer for another slice of lithium-rich Sichuan Tibetan landscape: “Businesses with no direct connection with lithium mining have also invested in mines and battery-making. In November alone, four large investments were made by companies outside the lithium industry. Shenyang Cuihua Gold and Silver Jewellery Co. Ltd. 沈阳萃华金银珠宝股份有限公司 (its shares trading on Shenzhen Stock Exchange 002731.SZ ), a jewellery-maker, bought a 51% stake in a Sichuan province-based lithium mine for 612 million yuan, saying that the investment would diversify its business and strengthen its competitiveness.”

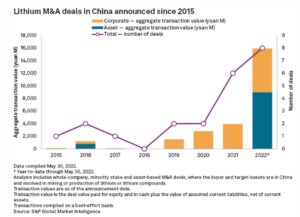

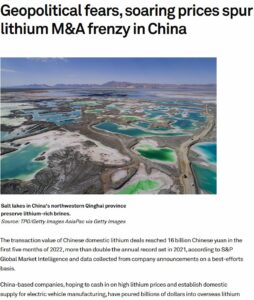

The lithium craze has triggered the most intense lust in China to own a slab of Tibet, with deal making at fever pace. Fortunately investor advisers, such as S&P Global Market Intelligence, follow this hectic buying and selling of Tibetan landscapes, none of which involves asking Tibetans.

In this fevered bubble of overbidding, the Tibetans of Nyagchu Tibetan Autonomous County, in the Kandze Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, were never informed their hill pastures were being sold, so their lands could be excavated and carted away. The Tibetan pastoralists of Nyagchu were utterly incidental.

Yet it is they who will be most impacted, should rock lithium mining go ahead, not only at this deposit but also at nearby deposits owned by Tianqi and Youngy, more on whom below.

But bubbles do burst, as did tulipmania, the South Sea Bubble, and crypto bitcoin. Already, in early 2023 lithium prices sank again, reverting to closer alignment with historic levels. The jewellery makers and speculators may already be frothing their FOMO mouths.

These extremes leave Tibetans with no way to gauge whether the promised large scale extraction will happen, or what will happen to their lands and livestock if the miners move in big time. What they do know is the disasters of 2013 and 2016, when sulphuric acid leaking from small scale lithium mining close by resulted in mass fish kills in local rivers.

Despite the mania for Tibet as a pricy asset class, there is little clarity as to whether the boom in new electric vehicle sales worldwide will intensify lithium extraction from Tibet, and whether the lithium will come from rock lithium in Kandze or salt lake lithium from the Tsaidam Basin and upper Tibet.

This blog explores the opportunities and challenges of the 2023 lithium battery boom, the tech backstory of how the lithium in batteries is made, the globalisation of Tibet’s mineral endowment, and China’s plan to dominate all stages of electric car manufacture, starting with onshoring the raw lithium supply by turning to Tibet.

YOUR NEW CAR AWAITS YOU

2023 is the year Chinese-made lithium powered cars arrive in the hip showrooms of car dealers in the rich countries, their critical minerals extracted from the conflict zone of Tibet and made into batteries in Tibet.

On Kurfurstendamm, Berlin’s top retail strip, China’s lithium cars strut their showroom stuff. This is high end, premium-priced capitalism, a global fusion of Chinese extraction and engineering with contemporary brand management and uber cool design.

Badged as the green future, these sporty cars above all boast design targeting rich male egos, featuring fast acceleration, the bodily thrill of outpacing everyone else, the full throttle competitive urge that makes you an alpha early adopter, ahead of the pack in every sense.

By far the biggest component of these Chinese cars, and the most expensive, is the battery. It has to be big to go fast. Much smaller batteries would suffice, if the point is actually renewable energy efficiency, long battery life, saving the planet, sparing Tibet the worst of China’s extractivism and polluting heavy industrialisation. But that’s not the point. The marketers understand their alpha male mark so well, the cars gleam and the dirty origins in the salt lakes of Tibet are concealed.

Just imagine, in this Anthropocene age of acceleration, being able to accelerate faster than anyone, and still boast of owning the coolest renewable car there is. An irresistible combo. Gone is the throaty roar of revving up the petrol engine of your muscle car, to advertise your turf, but in its place is the sleekest of design, the fastest acceleration, so the newest predator struts his stuff.

In China, any company fixated on accelerating its growth trajectory has piled into lithium battery manufacture and from there into making the cars that wrap around the batteries. So many Chinese enterprises have found the lithium battery shortcut to wealth accumulation so attractive, boosted by state subsidies, that soon there will be a shakeout. May the slickest survive.

If the underfloor battery has to be far bigger than necessary, and the environmental footprint hidden in far Tibet, no problem. In rich countries, no-one wants a small car any more, not even in India could a small and cheap car cross the barrier of the male ego. One of India’s richest men, Ratan Tata, found this out the hard way, when in 2008 he launched the Tata Nano, little bigger than an auto-rickshaw, only to have it flop. “’A Nano is always bandied about as a poor man’s car. Nobody wants to be caught with it,’ said Punnoose Tharyan, editor of India’s Motown magazine.”

The Nano was at first petrol-powered, then an electric model came in 2010. No sale. Bigger is better. Exit the Nano. The billionaire had no idea what the little guy would or wouldn’t buy.

As recently as 2019 an Australian politician engineered a “miracle” election victory by saying “I’ll tell you what – [a lithium battery powered car is] not going to tow your trailer. It’s not going to tow your boat. It’s not going to get you out to your favourite camping spot with your family. [Opposition Leader] Bill Shorten wants to end the weekend when it comes to his policy on electric vehicles where you’ve got Australians who love being out there in their four-wheel drives. He wants to say see you later to the SUV when it comes to the choices of Australians. And this is fundamentally the difference between us and Labor when it comes to these issues.”

No way. If we are going to go electric, it’s gotta be big. Vroom, vroom.

This big moment, when Chinese electric cars and their Tibetan batteries hit it big time, in the European market, has been a while coming, decades actually. Over that time, as smart money has shifted into the car makers, battery makers, lithium, copper and nickel miners, the prospect of profit now outweighs the risks. Yet the risks are many, and some are new. The electric car boom in Europe comes at an odd time, when China’s developmentalist, state-sponsored and state-subsidised boom in select “national champion” industries, is now seen across Europe as unfair. Europe is re-evaluating its basic assumptions about China, shaken out of its complacent assumptions that Europe can always stay ahead of China in high tech, and complacent slogans about making China “just like us” through win-win prosperity. Wandel durch Handel: change through trade. As if. So yesterday, it sounds ridiculously naïve and self-serving now.

In today’s world the European auto industry is being beaten at its own game. The Europeans gambled disastrously on the eternal demand for the internal combustion engine (ICE), missed the battery -powered shift, and is now urgently trying to catch up. Maybe too late, the Chinese are at the door.

So this is the moment Tibetans have been waiting for, when Tibet is no longer far over the horizon; it is now in your pocket, powering your mobile phone, now in the driver’s seat powering your car.

Tibetans held off advocacy over China’s extraction, and polluting processing of lithium in Tibet until now, but now is the time. Arguably, if the Chinese battery-cum-car companies succeed as planned, as early as 2024 they will be so entrenched in the European market they cannot be nudged out. Not only gleaming showrooms and fast cars, but also plenty of Chinese factories across Europe turning out both the lithium batteries and the cars and buses, providing employment, embedded in European economies. This is the turning point.

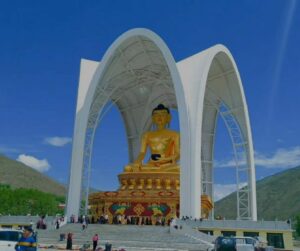

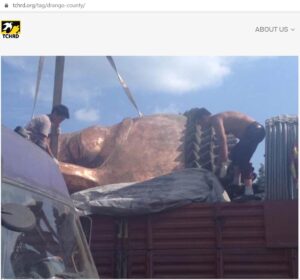

Chinese investors, hot to ride the lithium boom hope it will accelerate them fast into value creation, accumulating wealth quickly from remote Tibetan geographies they couldn’t find on a map. Yet Sichuan’s Kandze prefecture is on the map and in the news for something quite different: value destruction. In this rural prefecture, the devout Tibetans of Drago County, 150 kms from the lithium hills, managed to assemble RMB 44 million, to adorn the hills with a 30m high statue of the Buddha, to watch over them, guaranteeing his blessings to all who ask. The Buddha was protected by an auspicious parasol, a chattra; (Tib. gdugs), a symbol of protection of all against affliction. As soon as it was finished, local government cadres demanded it be demolished, and Chinese contractors moved in to complete the destruction. Value creation, value destruction.

Lithium can be found all over the world, though seldom in concentrated form. Being plentiful, the human body has uses for lithium, in small amounts. Back in the 1940s an Australian psychiatrist figured out that tiny amounts of lithium in the diet elevated the mood of depression, and levelled out the mania of bipolar. Ever since then, lithium has been a standard medication for bipolar.

But now we have a new disease caused by lack of lithium: fear, of missing out.