What to expect in 2023: A series of blogs about the short term future of Tibet

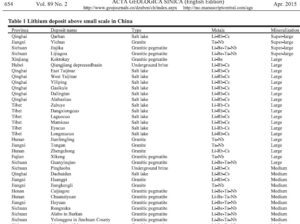

Can there be more to say about lithium? Well, yes: a lot is happening, with big impacts on troubled parts of Tibet. Please do read on. Or for the story from the start: https://rukor.org/lithium-lithium-lithium/

Blog #3:

TIBET GOES GLOBAL

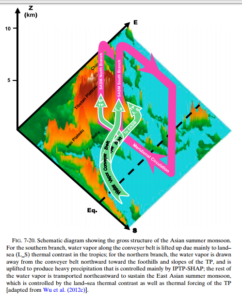

Climate change in Tibet affects climate in Japan, USA and right across the northern hemisphere. Chinese scientists now say the fast heating climate of Tibet is a global climate tipping point, as is the West Antarctic ice shelf, to which Tibet is teleconnected. Tibet is global.

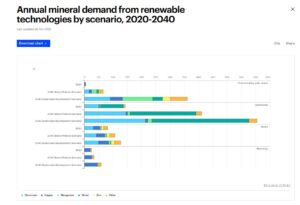

As a planet, we are closing in on that tipping point, beyond which it all gets out of hand, so the scientists tell us. So we need urgent solutions. Lithium-ion batteries are likely to be a major part of that solution.

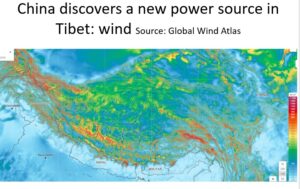

What is less well known is that all the drivers of climate heating -mineral extraction, emissions, pollution, industrialisation, urbanisation- are intensifying in Tibet, to the point where the industrialisation of Tibet has global consequences. The lithium boom is the latest of a series of Chinese manufactured landscape investments in Tibet. Before today’s lithium boom, there were the chromium boom, the copper boom and the hydropower boom that turned Tibet into an energy exporter. Then came the solar power and wind power booms, feeding ever more electricity into China’s ultra-high voltage power grids that transmit electricity west to east, from Tibet to the power-hungry industries of coastal China.

Next will be the pumped hydro boom that makes the landscapes, rivers and dammed lakes into giant batteries whose purpose is to balance wind and solar power generation with distant urban demand.

This combination of technologies is transforming Tibet into what China always dreamed the plateau could and would be: a treasure house of the west, Xizang in Chinese, which happens to be China’s official name for central Tibet.

We now have one of China’s most powerful corporations -State Grid- seriously proposing that a global ultra-high voltage grid could be built interconnecting the entire planet, with much of the electricity coming from the Tibetan output of hydro, solar and wind power. Tibet is on a trajectory to become the planetary island in the sky that powers the future, including the transition from coal and oil, away from the fossil-fuelled industrial revolution and wealth creation machine that is now so yesterday. The next industrial revolution -the fourth- will be decarbonised, sourcing its endless demand for power from lithium-ion batteries, solar, wind, hydro and pumped hydro; with Tibet the supplier with the lot. The coming industrial revolution, like its predecessors, will generate great wealth for those in command of the new tech, and the new landscapes of production, in Tibet.

This new tech utopia will be brought to you by Chinese corporations, guided by the party-state, which has explicitly commanded intensified exploitation of Tibet.

DO WHAT IT TAKES?

We live in anxious times, climate doom looms. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if tech could just switch us from carbon emissions to green energy, and we can all keep going, business as usual?

If we are now in the decarbonisation era, we need above all to decarbonise the atmosphere of the planet, which means decarbonising the industrial sources of carbon emissions. Instead, China is planning to intensify extraction from Tibet, and accelerate energy intensification of Tibet.

Fortunately environmentalists, economists and policy makers around the world are looking closely at this gleaming new tech, no-pain promise of seamless transition. As usual, simple solutions to complex problems turn out to introduce many new problems. Those problems bear heavily on Tibet. We now face more than today’s lithium extraction bubble, Tibet is to be the source of much of the greatly intensified extraction of copper the new industrial revolution requires, plus the batterification of Tibetan rivers, plus solar, wind, hydro and more solar. This adds up to multiple impacts on a plateau everyone calls fragile.

“GREEN” ENERGY DOWNSIDES

Our new era of decarbonisation has been oversimplified, into a binary of evil carbon to be abolished by good green energy, the rich can get richer, without interruption. In order to believe this fairy-tale, many inconvenient truths have to be ignored. A decarbonisation that maintains our energy addiction as usual means an intensification of copper and lithium extraction, and an intensified repurposing of landscapes of Tibet.

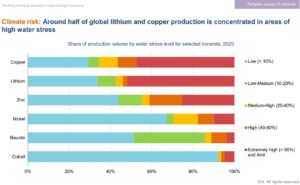

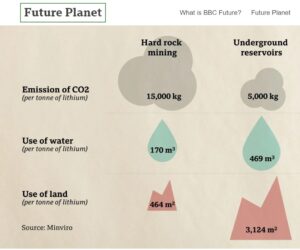

What is seldom explicit is the intensification of impacts as battery deployment increases, while fossil fuel burning decreases. However, there are a few who have looked closely. “It has long been known that building solar and wind systems requires roughly a tenfold increase in the total tonnage of common materials—concrete, steel, glass, etc.—to deliver the same quantity of energy compared to building a natural gas or other hydrocarbon-fuelled power plant. Beyond that, supplying the same quantity of energy as conventional sources with solar and wind equipment, along with other aspects of the energy transition such as using electric vehicles (EVs), entails an enormous increase in the use of specialty minerals and metals like copper, nickel, chromium, zinc, cobalt: in many instances, it’s far more than a tenfold increase. As one World Bank study noted, the “technologies assumed to populate the clean energy shift … are in fact significantly MORE material intensive in their composition than current traditional fossil-fuel-based energy supply systems.”

Once the expected boom in lithium and copper demand arrives, the pressure will intensify. “But the material demands will become hard to ignore if the world’s economies all simultaneously pursue similarly ambitious policies to displace the fossil fuels that currently supply over 80% of all energy. The vision plan from the International Energy Agency (IEA), which has been adopted and even exceeded by some policymakers, has solar and wind providing some 60% of net new global energy supply over the coming two decades.”

Another warning comes from Christine Lagarde, head of the European Central Bank, in January 2023 reminding us the new “clean green” technologies “are highly resource-intensive in their installation phase. Getting the global economy on a path to meet the Paris Agreement goals could see total mineral demand from clean energy technologies quadrupling by 2040. This threatens a new era of competition for resources.”

Transitioning from coal, oil and gas to lithium, copper, nickel and cobalt is a huge restart for industrial and preindustrial landscapes alike, with major costs to be borne by Tibet as a suitable “geography” for converting the rays of the sun, the blowing of the wind and the rush of mountain rivers, into electricity that then has to be transmitted to hubs, which then send the generated electricity right across China, west to east, to the factories the world depends on.

Not only is Tibet a “geography” assigned a high suitability rating for extracting energy, it is also in the language of investors a “play.” It may even be a “pure play” in the sense of being uniquely capable of supplying “green” energy from ores underground, from solar panels, wind turbines, hydro dams, pumped hydro and the copper-wired power grids that connect them all. This makes Tibet attractive to investors, an investable worth attention, and a well-timed decision to invest when the Tibet boom is taking off. Tibet is a play. Investors take note.

China’s mastery of long-distance electricity transmission and solar power technologies, plus lithium extraction and battery manufacture, add up to a package of intended impacts on Tibet, since the plan is for the Tibetan Plateau to become a major source of lithium, hydropower, solar power, wind power and export that power right across China, west to east, to the big industrial users. The intensification of not only lithium extraction but also solar and wind power across Tibet are part of the one package, all transmitted via ultra-high voltage power grids that make Tibet a major energy exporter.

This can be seen in China’s official statistics for Amdo/Qinghai province. In 2016, wind power generation in Qinghai (where hard winds blow in from Xinjiang) was 100.1 billion kilowatt hours (kWh). By 2020 this had increased eightfold, to 815 billion kWh.[1]

Generating solar power in largely arid and sunny prefectures of Qinghai started earlier, and has also intensified greatly. In 2016 Qinghai generated 899.1 billion kWh of solar power; by 2020 this had increased to 1669 billion kWh. This makes Qinghai the fourth biggest producer of solar power in China.

Add to this the hydroelectricity generated by the nine-dam cascade China has recently completed on the upper Ma Chu/Huang He/Yellow River. Since the first big dam to interrupt the upper Ma Chu, the Longyangxia is now decades old, Qinghai’s hydropower output has steadily grown, from 1.606 billion kWh in 2005, more than doubling to 3.711 billion kWh in 2010, then close to doubling again in 2020. [2]

China’s mastery of the technologies of long distance electricity transmission -no longer a European tech monopoly- enable China to plan not only to power its’ world factories with electricity from Tibet, it promotes the prospect of powering the whole of Eurasia, including Europe, with electricity from Tibet. That might sound weirdly megalomaniac, but as early as 2017 the European Commission took this possibility seriously enough to commission a technical feasibility study, which reported that the politics of getting all Eurasian countries to agree is mighty complicated, but technically it can be done.

“Decarbonisation demands a dramatic reimagining of our modern economy. One of the most eye-catching visions is the Global Energy Interconnection project, an idea for a planet-spanning electricity grid first advanced in 2015 by the State Grid Corporation of China. The project purports to address two challenges of the renewables era: the intermittent character of renewable generation and the concentration of high-potential renewable bases in remote locations. According to the project’s supporters, its worldwide network of high-voltage transmission lines can help countries access greater volumes of renewable power from a more diverse array of sources, for a greener and more reliable grid.”

These fantasies, of a planet electrified by China, from Tibet, are extreme versions of what is seldom questioned. Tibet is there for China to do as it will. If Tibet is exploited as per China’s plans, that is labelled development and growth, for which Tibetans should be grateful. Yet these plans all push Tibet into what everyone wants to escape: heavy industrialisation, energy intensity, accelerating resource extraction, alienation of landscapes, rural depopulation, toxic mine tailings, pollutant discharges to air, water and land. These are still treated as “externalities” because they don’t show up on corporate balance sheets, or party-state propaganda as the necessary price of growth.

The downside externalities of the coal, oil and gas fired era are at last well recognised. For centuries we treated rivers, lakes, the seas, soils and entire global atmosphere as sinks into which we could expel all wastes, without cost or consequence. They would just magically disappear. The pollutants, including carbon, were externalities because they never appeared on the balance sheets of the corporations focussed solely on making money.

Classifying nature as external makes it vanish. The externalities of the new era are the environmental and social costs of extracting and processing the lithium, copper and other critical minerals that are essential to a decarbonised yet still lucratively profitable future. Inherent in the “green” and “renewable” tech revolution is a swathe of externalities nobody wants to talk about. These are the down sides of green tech, which bear especially heavily on Tibet.

Tibet, having been mapped as extraordinarily rich in both lithium and copper deposits, is scheduled to disproportionately bear those costs. This will be masked, enabling an all-positive story of progress to clean, green, boundless energy, with the downsides barely noticed.

The entire global transition to decarbonisation is today driven by the same rent-seeking and profit seeking that gave us the first industrial revolution, which was coal-fired. Now, if we are to survive the externalities of the coal-fired era, that now threaten all life on earth, we must plunge into the fourth industrial revolution, with its utopian dreams of the metaverse and its powering by lithium, copper, cobalt and nickel. As with the great transformation of the first industrial revolution, this latest industrial revolution may well succeed, because it will be profitable, at least for the few pioneers who boldly monopolise the new technologies that enable us to go on living normal, careless lives forever.

The buzz these days is “nature-based solutions”, repeated in COP after COP as the way ahead. In Tibet, sustainable, nature-based livelihoods have persisted for thousands of years. The way forward into a decarbonised, nature-based Tibet is to let it be itself

The growth trajectory China has planned for Tibet, implemented by party-state and corporate wealth creators in tandem, imprints onto Tibetan landscapes an extractivist ideology at odds with today’s “green energy”, zero emissions, protected planet, nature-based solutions.

The landscapes of the Tibetan Plateau are at unequal points on the extraction and growth path. When we look more closely at a plateau the size of Western Europe, with the aid of China’s official statistics, we find a base of industrial modernity entrenched in northern Tibet (Amdo), and from there neoliberal capitalism with Chinese state-backed characteristics is now spreading across Tibet.

Qinghai, far more industrialised, reports in much more detail, not only output of industrial products, but on the costs and profits of enterprises, big and small, and also by prefecture. A clear picture emerges.

COLONISING TIBET FROM XINING

For Chinese corporations, especially those based in the Qinghai capital, Xining, [Silang in Tibetan], now is at last their turn, due to the lithium battery boom at the heart of global decarbonisation, and they are determined to seize the moment. The mineral riches of the Tibetan Plateau are their ticket to wealth accumulation, and that accumulation becomes an end in itself, which is destined to propel them out of Tibet, all the way when possible to transferring their wealth to Vancouver or Sydney, well away from the rapacious CCP. Before they can achieve escape velocity, they base themselves in Xining, China’s biggest city on the Tibetan Plateau, with strong links to the industries of inland China, to the east. Xining is the springboard. At 1.6 million people, it is four times the size of Lhasa.

The greedy and selfish neoliberal focus on wealth accumulation, and the nation-building of the party-state, work together to reduce most Tibetan landscapes to raw material sources. For the CCP regime and for Chinese corporations, the Tibetan endowment of minerals, rivers to be dammed for hydropower, abundant sunshine for solar energy and powerful inner continental winds for wind turbines, are all fortunate givens there for the monetising, public goods for the taking, for making wealth and power.

To suggest that local Tibetan communities can and will benefit from China’s extractive regime seems unlikely, despite the constant rhetoric of the propaganda machine of Tibet’s fast-growing GDP and prosperity. Enriching Tibetans, even employing Tibetans as miners and industrial workers, is not on the agenda. The entire Tibetan Plateau is merely a “geography” that happens to be abundant in the raw materials on which material prosperity is based. China has never invested in the endogenous Tibetan livestock economy to add value to Tibetan comparative advantage in livestock products. For these reasons, anything like endogenous, self-generated development of Tibet continues to lag, outside of the Tsaidam Basin.

The reality is that China’s wealth is irrevocably concentrated in China’s east, far from Tibet, and there is a steady emigration of Han away from western provinces in order to access the far more diverse opportunities for wealth accumulation in the east. The 2020 China Census confirms this trend.

A major reason why Tibetans have so few opportunities to prosper is the racist stereotype among the dominant Han that Tibetans are lazy, backward, unmotivated by accumulation,[3] and are largely unemployable on any job that requires skill. As in the rest of the neoliberal world, work is steadily deskilled, in order to reduce wages, so even work Tibetans used to do -taxi drivers, road builders, building construction workers- are increasingly automated and even the precariat gig work once available is shrinking. To become operators of the machines that now do the work requires formal literacy in Chinese, and certification.

INDUSTRIAL TIBET BOOMS, TIBETANS REMAIN POOR

So we find a paradox: exploitation of Tibetan resource endowments is intensifying, yet Tibetans remain outsiders in a modern economy that has almost no use for them. On paper, Tibet is growing its GDP, yet Tibetans are routinely displaced from their lands and reduced to dependence on handouts, which inevitably pushes them to be loyal to the cadres who administer the transfer payments.

Central Tibet (TAR) continues to lag, while the modern sectors -urban construction and resource extraction- boom. The biggest copper mines are in Tibet Autonomous Region, but the value adding and profits are made at the smelters in Gansu and Qinghai.

Development economist Andrew Fischer argues that “the dominant structural trend facing these relatively poor peripheral areas is net outmigration, not net in-migration. Because outmigration is stronger among the Han than among minorities, combined with higher fertility and natural population increase rates among minorities (Tibetans in particular), there is a tendency for rising minority shares….The provinces with Tibetan areas outside of the TAR had either stagnant or declining populations due to net outmigration (as indicated when provincial annual growth rates are substantially lower than the average natural population increase rates)….. Moreover, such emigration is more prominent among the Han Chinese, who are mostly non-indigenous in the minority areas, are more urban, educated, and mobile in these western regions, and more culturally connected to other parts of China.” [4]

The era of letting some coastal residents get rich first may officially be over, but the concentrations of wealth are now extreme. The magnetism of coastal China as the central cluster of factors of production remains. Han who can go back east do so, and if successful in magnetising wealth, then plunge into the sea -the classic trope for going into business- and leave China altogether. Tibet remains peripheral in every sense.

MANUFACTURED LANDSCAPES OF TIBET

State Grid, a corporation so big and powerful it operates as a state within the state, does not wait for directives from Beijing; it declares its policies for “a new road for energy development with Chinese characteristics.”

Fortune magazine says: “State Grid, a Chinese state-owned power company, reported profits of $7.1 billion in 2021, up 19% from the year prior. China’s largest supplier of electricity and the world’s largest utility company brought in revenue of $461 billion in 2021, enough to make it the top-earning public energy company in the world.”

Having announced its master plan in March 2021, what State Grid needs from Beijing is enforcement imposed on the main electricity consuming provinces so they actually use the grid that pumps electricity from Tibet right across China. Much of that electricity has in recent years been wasted, because many provinces prefer the coal-fired power stations they own and operate.

State Grid, which calls itself “a major national weapon”, embraces the decarbonised future enthusiastically, promising it will “win the battle for blue skies. Accelerating the construction of electric vehicle charging networks, completing a highway fast charging network covering 176 cities.” Ensuring all electric vehicle users a fast charge of their fast car, with its lithium batteries weighing 50 to 100 kilos, means reliably supplying electricity on demand in each of those 176 top tier Chinese cities, 24/7. How to do this?

TIBET: MOTHER OF ALL BATTERIES

State Grid, while enthusing about all the “green” energy it can generate, and transmit, also faces the problems of renewables. The best endowed geographies for generating “green” energy aren’t where the demand is; and the peak demand hours aren’t when the maximum generating capacity peaks.

State Grid is confident it has the tech to master the “where” problem of connecting the upriver power generators with the downriver power consumers, but is still wrestling with the “when” problem. State Grid proposes a tech solution to this too. In order to ensure peak demand and peak supply are matched, it needs to build its own batteries that gather and store electricity during the peak production hours of the day, releasing it in the peak demand hours. However, battery technology is utterly unable to store and release sufficient energy to meet that demand, and any attempt at building such batteries would be prohibitively expensive.

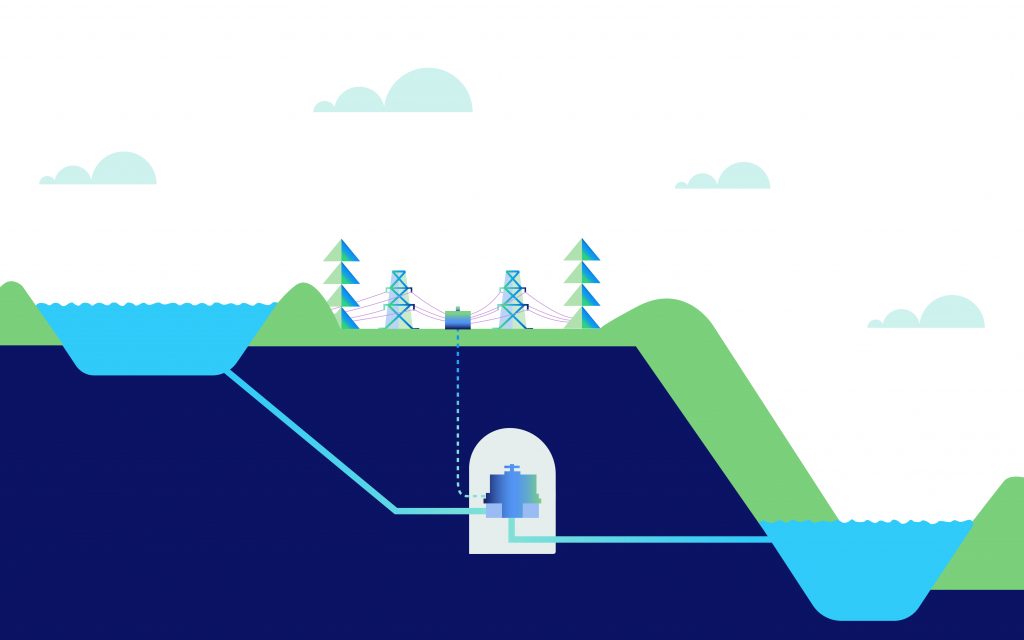

The solution State Grid proposes is to turn all the rivers of Tibet into batteries. Those fast flowing mountain rivers of the Tibetan Plateau are now valuable not only for their water but for the kinetic energy of their waters rushing down the steep valleys of the plateau edges. All that is needed, to capture that kinetic energy and release it on demand, in a daily cycle in sync with distant urban demand, is dams, a lot of dams, technically called pumped hydro.

Pumped storage may be rather new to many, but not to Tibetans, since the hydropower project on Yamdrok Yumtso that so shocked Tibetans in the 1990s was from the outset designed as a pumped hydro project to supply Lhasa with peakhour electricity by draining this most sacred of lakes to drive the turbines, then in offpeak hours pumping the water back up, from the Yarlung Tsangpo far below.

China made Yamdrok Yumtso into a giant battery. Construction began in 1985 and was completed in 1998. From China’s perspective, this pumped storage added value. From Tibetan perspective, of the long history of high lamas in meditative equipoise discerning in the movement of wind on the waters of Yamdrok Yangtso the first indications of where to seek reborn masters, this was a despoliation of value. Value creation/value destruction is a repeated pattern in China’s colonisation of Tibet.

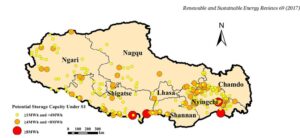

Qinghai, the most industrialised part of Tibet, and the location of massive solar installations as well as a cascade of 9 hydro dams on the upper Yellow River, is proudly taking the lead in implementing pumped hydro projects. In early 2023 Qinghai announced it has “researched and formulated the ‘Qinghai Provincial Pumped Storage Project Management Measures’, becoming the first province in the country to issue pumped storage management methods. This is the first batch of pumped storage power station projects approved by our province. The total installed capacity of the three projects is 7.6 million kilowatts, and the total investment exceeds 50 billion yuan.”

State Grid in 2021 stated its commitment to “vigorously develop hydropower, accelerate the development of hydropower in southwest China…. strengthen the system regulation capacity, vigorously promote the construction of pumped storage power plants.” This is necessary, according to State Grid because “wind power and solar power generation has a random nature, power generation ‘by the sky’, mainly to provide electricity.” This echoes the contemptuous attitude of Han elites, who accuse Tibetans of passively waiting for the heavens to provide, rather than mastering nature. Random is forbidden.

NATURE RECONQUERED

Ironies abound. In order save the planet and build ecological civilisation, mastery of nature is required all over again, but with a different technology. The landscapes of Tibet, especially the steep valleys of Kham, are to become batteries. In off peak electricity demand hours the turbines set into the rivers will generate electricity that pumps impounded water back up into an upper reservoir. In peak electricity demand hours in far distant cities, water impounded in upper reservoirs is released quickly, the turbines turn fast, the electricity is transmitted across China. Tibet empowers the world’s factory.

Already, in recent years, pumped hydro construction has surged. State Grid boasts that “a total of 21 pumped storage power plants have been started with an installed capacity of 28.53 million kilowatts, and the scale in operation has reached 62.36 million kilowatts to enhance the capacity of new energy consumption.” Thus China is on track to achieve “an important transformation of China from an industrial civilization to an ecological civilization, in line with the laws of human social development and the expectations of the people for a better life.”

The more China’s energy technologies are installed across the vast Tibetan Plateau, the more Tibet is denatured. The waters of the great rivers will flow upward and then down, in a daily rhythm dictated by industry, commuters and home makers in far Shanghai. River levels will be controlled remotely, by monitoring electricity demand in Beijing or Guangzhou, triggering an immediate fall or rise in river levels thousands of kilometres to the west. The landscapes of Tibet become slaves, lacking all volition.

POLLUTING, ENERGY INTENSIVE INDUSTRIES GO WEST

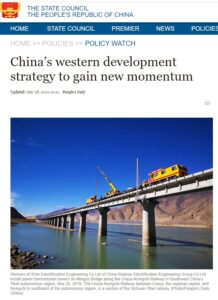

Yet another factor requiring Tibet to produce more electricity is the mandatory shift of heavy industry from east to west, as decreed by State Council communique #28 of 2010. This was two years before the Xi Jinping era.

By early this century, urban China had had enough of polluting, politically well-connected factories built in urban areas. Urban communities staged thousands of protests, many of them successful. Contention was frequent, and CCP leaders realised they needed a Plan B.

A top-down policy of relocating the most resource-intensive, energy-intensive and polluting industries westward, far inland, could be packaged as a win-win, clearing the skies of the big coastal cities, brining growth and development to the far west. But the result was highly uneven.

This policy has been implemented patchily in Tibet, much of which remains too remote, with scarce infrastructure linkages to the big cities of lowland China where consumer demand is greatest. The shift of industry to Chengdu, Chongqing, Lanzhou and most of Xinjiang has been much stronger.

The northern half of Amdo [Qinghai in Chinese] has been the most impacted by this 2010 decree, increasingly growing into a hub of dirty industries that are no longer welcome in eastern cities. The factory belt of Qinghai needs reliable electricity on demand, and gets it from the cascade of nine hydro dams recently built athwart the upper Ma Chu [Yellow River, Huang He] which were intended to export electricity to central China.

The State Council makes a case: “the pace of transfer of industries from the eastern coastal areas to the central and western regions of China has been accelerated. Central and western regions play the advantages of abundant resources, low factor costs and large market potential.” It all sounds so rational, logical, normal. The xibu da kaifa, open up the great west campaign, announced in 1999, had similar aims.

COMPARE AND CONTRAST UNDER-DEVELOPED CENTRAL TIBET & INDUSTRIALISED AMDO

According to the 2021 TAR Statistical Yearbook “mining and processing of non-ferrous metals” has become the biggest of TAR’s industries. Output in 2020 was valued at RMB 7.66 billion, a sevenfold increase on mining a decade earlier.

Second biggest industry is “production and supply of electric power and heat power”, at RMB 5.9 bn in 2020, an industry essential both to urban life and the extractive industries largely powered by hydroelectricity. Output value increased more than fivefold over the previous decade.

Third biggest is “manufacture of liquor, beverages and refined tea”, worth RMB 2.19 bn in 2020, almost doubling the 2010 value.

Fourth is “manufacture of non-metallic mineral products”, at RMB 1.03 bn. This could be basics of urban construction such as gravel and cement. Its output increase more than sevenfold over a decade, which fits the construction boom of recent years.

No other industry is worth a billion. Central Tibet remains, in Chinese eyes, an embarrassing laggard. Chronically underdeveloped, other than a bloated security & surveillance sector.

But extraction of nonferrous metals such as chromium and copper from mines in TAR from 2010 to 2020 leapt 700%, while the urban construction industries of sand, gravel, cement and electricity grew between 500% and 700%. These are the dominant industries, with the fastest growth curve, although the administrative/repressive superstructure imposed on Tibet from above remains by far the biggest economic sector.

Output in billions suggests a major transformation of central Tibet. Yet these reported output valuations, when compared with neighbouring Amdo/Qinghai, show a quite different picture. Qinghai is closer to inland China, and with stronger linkages over shorter logistic distances, and it has exploitable rivers, gas fields and oil fields. Thus its annual statistical yearbook (2021 as with TAR data above) tabulates industries that don’t exist in TAR. Table 13-6 lists the gross annual industrial output value of high-tech industries, including the “new energy industry”, which means the manufacture of lithium batteries, silicon for solar cells, maybe the ultra-high voltage power grids that export electricity from Qinghai into central China. In 2020 output was RMB 15.316 billion, double the entire TAR mining output that year. The same table also lists new energy vehicle production at RMB 6.6 billion and growing fast, according to Qinghai media.

This suggests a new mode of colonisation, very much in keeping with the 1999 “develop the west” policy, and the 2010 State Council decree that industries should move westward. These numbers are still small compared to Xinjiang, further north, which was better suited to settler colonialism, with fewer constraints imposed by altitude and terrain, and a more accessible endowment of coal, oil and gas.

So we can reasonably say central Tibet is both fast being remade with Chinese characteristics, yet is still a laggard; yet is rapidly growing linkages to lowland China, but still remains remote and bereft of the logistics infrastructure that constitutes an integrated supply chain. That may sound paradoxical, Tibet today is full of paradoxes.

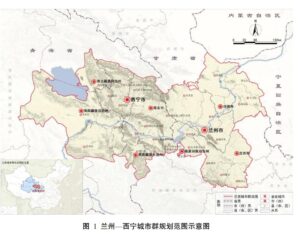

Another way of putting it is that central Tibet is being colonised from Qinghai. The transport linkages from Lhasa go first to Qinghai and Gansu provinces, then on to the rest of NW China. Corporations based in Xining, the Qinghai capital and by far the biggest city of the Tibetan Plateau, are at the forefront of the exploitation of central Tibet/U-Tsang. Xining is now officially merging with Lanzhou to form a megapolis of China’s northwest, mimicking the Chengdu-Chongqing megapolis of the southwest. Xining is bulking up, 兰西城市群建设 lán xī chéngshì qún jiànshè agglomeration of two provincial capitals scaling up together, is now officially happening. There can be no doubt who is senior. Lanzhou used to rule what a century ago became Qinghai, and it is no accident that in the Lanxi conflation it is the Lan that comes first.

Now Xining looks east to its neighbouring provincial capital, further down the Yellow River; while at the same time looking west and south to its Tibetan heartlands to source the under-priced producer goods both industrial cities need. Although the distance from Xining to Lanzhou is 200 kms, the plan is that everyone will be at most one hour apart, thanks to high speed rail. The prime beneficiary is Tsongkha (where religious reformer Tsongkhapa was from), now named Haidong, no longer a Tibetan town but a “fat city”长胖”了的城市 poised midway between the two provincial capitals.

Lanzhou is where Tibetan oil is refined, for industrial use. Electricity from the Ma Chu (Yellow River) hydro dams powers Lanzhou’s industries. Now, with a combined population close to six million, they will have the money and the muscle to commandeer what they want from the lands of Tibet.

This is most obvious with mining. So far, there is no metal smelter in Tibet, other than small-scale proof-of-concept ones. The smelting of all extracted minerals is done in Qinghai, and even farther, in Gansu. This requires trucking, or shipping by rail of ore concentrates as much as 2000 kms, a long, long haul distance that made economic sense in an era of cheap and endlessly available fossil fuels. In our present decarbonisation era this is dumb. Bombardier, the Canadian company making trains and diesel engines specifically for Tibet, is proud of having designed locomotives capable of sucking in enough oxygen in the thin Tibetan atmosphere, to burn fossil fuels over the lang haul not the smelter. Smelting is where the molten metals are poured off, highly pure. Since almost all Tibetan copper deposits also contain gold, silver and molybdenum, all are captured, highly pure, in the electrowinning smelter process.

Smelting is where the profits are made, reducing the mines in central Tibet to captive sources of raw materials, contractually bound to supply their owners, the smelters. So the wealth generated by the three stage process of ore extraction, ore concentration and smelter purification of metals, is wealth captured wholly by the third stage. This is the reason why the Tibet Statistical Yearbook does not even list copper as an industrial product of central Tibet, even though the (dwindling) output of chromium, over decades, is separately listed.

COLONISING TIBET FROM CHENGDU

Qinghai is colonising Tibet from Xining. Qinghai has competition, triggered by the recent, emphatic switch from lithium extracted from Qinghai salt lakes to lithium extracted from lithium rock in Sichuan Kham Kandze Jiajika/Lhagang.

Not only are China’s biggest lithium battery makes now owners of the Jiajika rock lithium deposit, Sichuan province now promotes itself as China’s industrial hub of the future. Sichuan, deep inland, has worked hard to attract the biggest corporations worldwide to the industrial “parks” that surround Chengdu. Now it has more to offer. Specifically, boundless hydropower from the dams on Tibetan rivers, and now the rock lithium of Kham Kandze, one of the two Tibetan prefectures of Sichuan.

In September 2022 Sichuan announced its grand plan for the lithium powered path to wealth, and the transfer of industries from coastal to inland China, enabling Sichuan to make not only lithium batteries but cars and computer chips. Ever since the central government shut down Sichuan’s energy guzzling bitcoin mining industry, built on cheap hydroelectricity from the dams on Tibetan rivers, Sichuan has been looking round for a new industrial wealth accumulation strategy.

The 2022 provincial decree is based on an abundance of rock lithium and hydro power, all sourced from Sichuan’s Tibetan uplands. That’s a winning combination, the province says, since those picky customers in “Europe and the United States and other mainstream markets have a strict traceability process, must ensure the use of clean energy in production.”

Sichuan hydro is the winning ticket. Several of the world’s biggest carmakers, in the midst of going all-electric, already have major factories in Sichuan, including Volkswagen, Toyota and Volvo.

In this grand vision, you ain’t seen nothing yet; this is going to get much bigger: “Sichuan’s proven lithium resources account for 6.1% of the world’s lithium resources and 57% of the country’s, topping the list, mainly concentrated in the two major fields in Ganzi [Kandze] and Aba {Ngawa Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture}. At the same time, due to the proximity of Tibet and Qinghai, the supply of lithium resources for Sichuan from salt lake is also relatively easy. It is expected that by 2025, Sichuan will form a lithium mining capacity of 5 million tons and a basic lithium salt capacity of 600,000 tons.”

[1] China Energy Statistical Yearbook 2021, table 3-13

[2] China Energy Statistical Yearbook 2021, table 3-11

[3] Wang Xiaoqiang and Bai Nanfeng, The poverty of plenty, translated by Angela Knox, Macmillan, 1991

[4] Andrew M Fischer, Chinese Population Shares in Tibet Revisited: Early insights from the 2020 census of China and some cautionary notes on current population politics, International Institute of Social Studies Erasmus Working Paper #684, July 2021, 5,8-9