EVERYTHING OLD IS NEW AGAIN

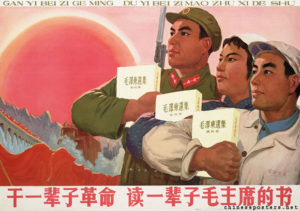

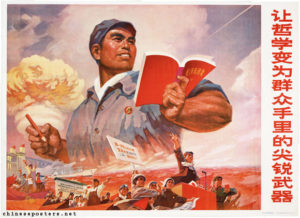

China is now ruled by the “Thought” of one man.

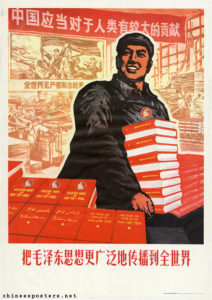

Xi Jinping has thought about everything, as his multi-voluminous collected thoughts, translated now into many languages, weightily attest. Xi Jinping is now in charge of everything, in a position to enforce his thought on all under heaven who are under his control. Xi Jinping has an army of authoritarian personalities eager to be his enforcers, to prove their loyalty to the commander-in-chief.

What, then, is that “Thought” sixiang 思想? It might give us a clue as to why official China finds it so hard to see and hear Tibetans as human equals.

Excessive mentation is a familiar category in Tibetan Buddhist analysis of how we manage to suffer, by confusing ourselves as to what is real and substantial, and then seek who we can blame. Conceptual confusion, mistaking the external for the real, ignoring the internal currents of mood colouring our perceptions, is a classic starting point for Buddhists in diagnosing how we wander, seizing on this or that as the solution, only to finds it yet again fails us. We imprison ourselves in our ideas, habits of mind, preconceptions and misconceptions. We think we need to think our way out, only to find the more we think the more uncertain it all gets.

That one man among the largest human population on earth has the answers to everything, and was clearly predestined for that unique role, is perhaps a delusion. Eventually, this will become apparent to all, as it inevitably must. But that could take a long time, and in the meantime everyone must conform, at least outwardly, to the writ of “Xi Jinping Thought.”

Outside China, few have actually read up on their Xi Jinping Thought, attractively bound into volumes uncannily akin to the Collected Works of Mao Zedong. A plunge into the three volumes issued so far reveals not only someone who has thoughts on all topics, but also a politician’s eye for addressing the concerns of all his publics, saying much to acknowledge the many constituencies. In fact, Xi Jinping has so much to say that it is not easy to discern where he stands on many issues, beyond the obvious, overriding insistence that the Party is right about everything, in command of everything, is to be trusted for its unique capability to steer China through all problems, and is to be obeyed. Fortunately, he now has exegetes who can tell us (and him) what he actually thinks, more below.

THE START AND END, GROUND AND FRUITION

Whatever the problem, the Party is the solution. That is axiomatic, a given, beyond dissent or discussion. However, the Party also needs China to have problems, so the Party can solve them. Without problems, there would be nothing for the Party to do, beyond getting richer. Its’ monopolisation of power and wealth would in turn become questionable, even becoming a problem.

Tibet is a classic wicked, unresolved problem for China, partly because Chinese certainties melt in the thin air of Tibet. There are willing ideologues, who routinely remind Party leaders that Tibet and Xinjiang are serious chronic problems, and coercive assimilation is the answer. Few Tibetans could name these elite intellectuals, even though they have been highly influential among central leaders always on the lookout for new threats to be managed by a disciplining, controlling, centralised party-state. We should be studying their writings.

Tibetans prefer to look within, to start with the basics, rather than point at the delusions of others. What could be more basic than discerning why we suffer? Buddhism emphasises the reality of suffering, and its causes, not out of morbid fixation, or pessimistic assumption that this is our human lot, but with great confidence that suffering (not pain) can cease, and that there is a clear path to that cessation. That path is up to each of us to implement, there is no external saviour who can do it all for us, so each of us has our work cut out for us, to cut through ideas, habits of mind, dogmas, fixations, to dissolve our prejudices and assumptions and awaken to whatever arises and fully experience it. That’s enough to keep you busy.

That is probably why Tibetans seldom fixate on the delusions of others, still less the reigning delusions of a distant party-state, isolated from reality behind the walls of its old imperial palace headquarters, Zhongnanhai. Tibetans in Tibet know nothing is gained by critiquing the party-state’s delusory insistence on generating endless problems that only party-state leadership can then solve. Tibetans outside Tibet very seldom take ideology seriously, or bother to read Xi Jinping Thought, assuming it is at most propaganda for an unchanging agenda of oppression and exploitation in Tibet. So it remains oddly up to a nonTibetan blogger to say the new emperor has clothed himself in Thought which amounts to very little.

Where to begin?

Since we know how and when “Ideology” was first coined, we begin at the beginning, in 1796, in the midst of French revolutionary terror, with the aristocrat-cum-revolutionary Destutt de Tracy, who sought ways of discerning what is knowable, the core concern of epistemology. This is familiar territory to Buddhists, who thousands of years ago came up with the two seemingly contradictory truths, the relative truth and absolute truth, that apparent, relative reality is relatively valid but ultimately contingent and misleading; while absolute truth is that all propositions, ideas and concepts are empty of substance. From the ultimate perspective, even the Buddha, nirvana and enlightenment are empty, not to be clung to; yet from a relative perspective they are efficacious as objects to be trusted while on the path within, the path of discovering the nature of mind. So the two truths are not only not contradictory, they stand together, indispensable to each other, supportive of each other as guides on the path and expressive of the inexpressible ultimate realisation beyond language.

THE INVENTION OF IDEOLOGY

In the west, the question of what is truly knowable has persisted, without satisfactory answer. The revolutionary Destutt  ambitiously decided it ought to be possible to at last resolve the deep-seated dualisms of western thought, the split between mind and body, matter and spirit, things and concepts. This he called “Idéologie.” Not only would this be a new science, “to analyse the process by which our minds translate material things into ideal forms”, it would be a science of sciences, the ultimate arbiter of what is true.

ambitiously decided it ought to be possible to at last resolve the deep-seated dualisms of western thought, the split between mind and body, matter and spirit, things and concepts. This he called “Idéologie.” Not only would this be a new science, “to analyse the process by which our minds translate material things into ideal forms”, it would be a science of sciences, the ultimate arbiter of what is true.

“The only way to avoid the sceptical position that true knowledge is impossible, so it seemed to Destutt, would be to analyse the process by which our minds translate material things into ideal forms. This modest proposal was readily adopted by authority, institutionalised in the section of the Institut de France which dealt with moral and political sciences, and it was given the name ‘Idéologie’: the science of ideas. Ideology thus originates as a ’meta-science’, a science of science. It claims to be able to explain where the other sciences come from and to give a scientific genealogy of thought. This amounted to a claim of epistemological superiority over all other disciplines. Destutt was thus able to claim that ‘Idéologie’ achieves a momentous philosophical breakthrough, by transcending the ancient oppositions between matter and spirit, things and concepts. By observing the movement by which sensations are transformed into ideas, it ought to be possible to understand, and so to avoid, the ways in which such erroneous patterns of ideas come into being. The new discipline of ‘ideology’ thus claimed to be nothing less than the science to explain all sciences.”[1]

From a Buddhist perspective, this quest for the foundational originary source is a futile exercise. The logical possibility of establishing an aetiology of ideas, a genealogy of thought, in practice gets hopelessly entangled, only generating further confusion. That was the discovery of the historic Buddha, and the subsequent experience of those who followed him. Thus the Buddhists strongly advise meditators not to follow thoughts, not to become fixated on the contents of specific thoughts, or to seek to capture the moments before or after any particular thought, as if to capture its origins or destination. To do so is to disappear down a rabbit hole, into infinite possibilities, none of which can be ascertained. In Buddhist tradition, to meditate is to avoid the extreme of ruminating on the contents of thoughts, and avoid the opposite extreme of trying to empty the mind of thoughts. The meditator allows thoughts to arise and dissipate of their own accord, without getting drawn in to specifics, and without trying to push thoughts away. This is the beginning of mindfulness, which is not necessarily about achieving a calm, thought-free mind.

That path never occurred within the western tradition, which has continued its obsession with origins, aetiologies, ideals and purity. To this day the dualisms of man and nature, mind and body, self and other continue to elude elision. China, in the name of science, now also struggles to reconcile nature and culture, having abandoned many its own traditions. Tibet may pay a heavy price, redesignated as depopulated nature counterbalancing China’s accumulative urban culture.

It is not hard to see how a party-state committed to the Thought of one man as the solution to all problems is attracted to a “science of science”, a grand narrative that promises to deliver top-level design solutions for anything and everything. The more China experiences the strains and contradictions of rapid modernisation, urbanisation and highly concentrated wealth accumulation, the greater is the search for stability, for definitive answers. Ideology, specifically Xi Jinping ideology, is the answer.

It is not hard to see how a party-state committed to the Thought of one man as the solution to all problems is attracted to a “science of science”, a grand narrative that promises to deliver top-level design solutions for anything and everything. The more China experiences the strains and contradictions of rapid modernisation, urbanisation and highly concentrated wealth accumulation, the greater is the search for stability, for definitive answers. Ideology, specifically Xi Jinping ideology, is the answer.

Yet the idea of ideology, proposed by a French revolutionary at a time when the revolution ate its own children, opened up the possibility that the science of discovering the source of all ideas would subvert all certainties, make all truths relative and contextual, all conclusions provisional, all finality disputable. “To ‘unmask’ the source of ideas was to deny them absolute validity. ‘Idéologie’ involved a thoroughgoing scepticism towards all authoritative knowledge, which must issue in continual chaos and [in Napoleon’s words] lead to the rule of bloodthirsty men.’”

Napoleon, determined to put the revolution behind him, specifically denounced Destutt and ideology. “If the ideologues were allowed to pursue their millennial aims, he foresaw a permanent revolution, a maelstrom in which ideas were continually being unmasked, invalidated and replaced by new ones.” Napoleon, not one to shrink from the rule of bloodthirsty men as long as he was that man, was determined to impose stability, which is also the obsession of the Chinese Communist Party.

Destutt and Napoleon came up with the two, opposed meanings of “ideology” familiar to us to this day. To the idealist revolutionary, ideology could become the Supreme word that judges all ideas, explains everything. To Napoleon, and the Buddhists, ideology obscures, confuses, reifies, overdetermines everything.

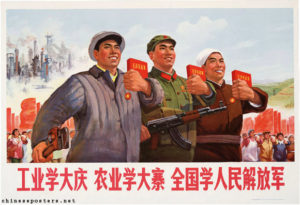

Xi Jinping Thought, more fully ‘Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era’ 习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想 , is basically all about maintaining stability and thus party rule, in a time of rapid change and deep social strains. Mao Zedong may have been attracted to permanent revolution, but not today’s Party. Forget class war.

PARADOXES, COMMUNIST AND BUDDHIST

Thus the paradox: ideology from the outset held the millennial promise of a definitive source and thus definitive answers to pressing problems; but also the prospect that all answers could be subverted, destabilised by the elevation of scepticism as the science of sciences. In today’s stressed China, the last thing the party-state wants is to legitimate questioning of its truth, embodied in Xi Jinping Thought.

The two truths of the Buddhists can also seem paradoxical. How can both be valid if from the ultimate perspective everything that is only relatively, conditionally, consensually, socially true is actually empty? Doesn’t ultimate truth negate and cancel relative truth? Isn’t ultimate truth all that matters and relative truth is at most a feeble fiction that glues society together, but which can’t withstand logical examination?

The Buddhists say this is a misunderstanding. Not only do the two truths not contradict, they support each other. Conventional truth may exist only by consensus, yet it shapes us powerfully. So if we can find an exemplary person, who has fully taken the inward path, transformed the self, and is a trustworthy guide, it is very efficacious to trust them, to emulate, to listen carefully to their suggestions, and believe it is indeed possible to change from being self-centred and forever anxious, to becoming more accommodating, no longer seeing others as problems to be negotiated. While it is true the teacher, the teachings, the self and indeed all phenomena are empty of substantiality, the imagination that habitually leads us to feel threatened is also an imagination enabling liberation, by imagining ourselves differently, able to accomplish all that sentient beings yearn for. Penetrating insight into the emptiness of all ideologies goes together with faith in a reliable teacher, even if that exemplary teacher is no exception to the insistence that form is emptiness, and emptiness is form.

Those three volumes of Xi Jinping Thought include a retrospective publication of Xi Jinping’s speeches showing he was destined for greatness. In hindsight, his collected speeches are testimony to his prophesied rise.

This ascent is in turn part of a much greater narrative now retroactively forming around his ascendancy and apotheosis, in which Xi Jinping becomes the continuity of all that is great in Chinese Confucian tradition, a worthy successor to the great men of 5000 years ago, who carries China singlehandedly into a glorious future with his seamless fusion of Marxism and the best of Chinese traditional characteristics.

THE GRANDEST OF GRAND NARRATIVES

The most coherent encomium proclaiming Xi the essential man of these times comes from a professor of constitutional law, for whom the Party’s insistence it is above the law and the Constitution is proof of Xi Jinping’s greatness. The author of this influential intellectual juggle is Jiang Shigong, 强世功 who takes 18,000 words (in translation) to position Xi Jinping and his Thought as China’s predestined saviour, in a teleology stretching back 5000 years. Jiang makes a handsome tribute payment, in obeisance to the righteous new emperor who will realise the China Dream.

What is interesting is not his predetermined conclusion, but how he gets there, which involves smoothing out all the bumps, reverses, failures and sharp turns in party history and the whole of Chinese history. Grand narratives don’t get grander than this. Although Jiang enthusiastically embraces the Marxist idea of contradictions and their resolution, his history of governing ideas irons out all the wrinkles. Even the Cultural Revolution, the crisis of 1989, Mao’s disastrous Great Leap are all integral to China’s progress.When China’s revolution, echoing the French revolution, eats its own children, he is along for the ride.

Inevitably, much is airbrushed out in this sweep of continuity, with its repeated cycles of renewal. The foreign dynasties of Mongols and Manchus that ruled China for several centuries are mentioned only in passing. The turmoil of the civil war of the 1940s, the May Fourth generation’s repudiation of Chinese culture, the radical revolutionary class warfare against the educated and especially against Confucius are rarely alluded to. Continuity is all.

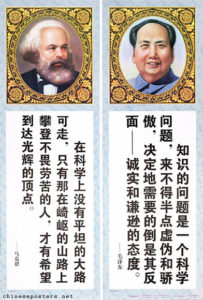

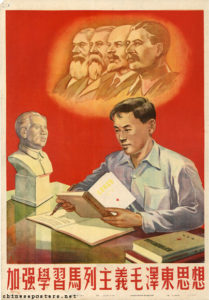

Jiang Shigong is far from the first to stitch together this kind of grand narrative proclaiming Confucianism as the root, source, fons et origo of today’s China. This has been done before by liberal intellectuals hoping to generate a backstory that propels China to not only modernity and wealth but also democracy and a state that limits itself. There has also been a new left, among Chinese intellectuals, who persist in revering Mao, who usually regret Deng Xiaoping’s capitalist turn, and the blame heaped on Mao since, not only for the violence and famines, but also for his failures of development and prosperity. To the new left, China’s embrace of Marxism with Chinese characteristics was a brilliant innovation.

What makes Jiang Shigong’s story weaving unique (so far) is that he manages to combine a New Leftist deferential tribute to Mao, including Mao’s repudiation of the Soviet repudiation of Stalin, with deep filial loyalty to the Confucian ancients. That’s quite an achievement, but in Jiang Shigong’s telling, it is all a coherent story, all culminating in the arrival of Xi Jinping.

Along the way Jiang makes lengthy detours to disown any ideas not originating in China, as superfluous, superseded by the Party’s pursuit of Chinese characteristics. Marxism with Chinese characteristics, or the Sinification of Marxism, beginning with Mao, has made such progress that Jiang declares: “We can say that Xi Jinping’s new reading of communist concepts is a model of the Sinification of Marxism in the new era, in which Marxism must not only be integrated into China’s current situation but must also be absorbed into Chinese culture. For this reason, communism’s highest spiritual pursuit and the realization of the great revival of the Chinese nation are mutually supporting and complementary, and together have become the spiritual pillars through which Xi Jinping has consolidated the entire Party and the peoples of the entire nation. When the Soviet path toward the modernization of socialism completely failed, due to the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, China lifted the great banner of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics onto the world stage, and it became a powerful competitor to Western capitalism as a model of development. Scholars have pointed out that if, at the outset, socialism saved China, now China has saved socialism.”

This is Jiang Shigong’s gift to the leader, marrying Marxism, communism, socialism, concentration of power in a party-state that is above the law, and a market economy, into a Confucian mould, “ushering in a new era in human civilisation.”

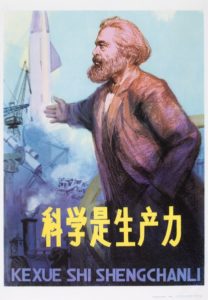

Having made Marx thoroughly Chinese, Jiang turns to a much harder task of repudiating modern western rationality as having anything to do with China’s current path. Anyone who has looked even briefly at the massive output of Chinese scientific research might see a very familiar subject/object dualism, a fixation on problem/solution, a scientism that locates truth in objective numbers rather than in situated local knowledges of customary custodians. Jiang acknowledges that “In the past, we understood this philosophy of mastery as modern science that destroyed religious superstition and established the central importance of man, and that produced the opposition between subject and object that followed the objectification of the world through a scientific epistemology. For this reason, the modern Western philosophy of mastery is also seen as the philosophy of epistemology. This philosophy has an intimate link to Western political life.”

Jiang understandably connects this dualism to Christianity and to the ancient Greeks. One is either a master or a slave: “For the Chinese people, this is a basic choice between two personalities, national characters and spiritual lifestyles, a choice between being part of the Way and being someone’s tool. It’s like when two people fight. Some people, when they lose, give up completely. They grovel in defeat and become submissive, like a little brother or a hired thug. Other people, even if they lose, refuse to admit it but instead fight back and eventually defeat their opponent. The former has an easy life but lacks dignity; the latter knows that to protect his dignity he will have to follow a difficult and painful path. In Western philosophy, these two personalities constitute the philosophical difference between master and slave.”

Has China somehow managed to transcend this Western dualism, and instead embrace the Way? Has today’s China transcended scientism’s contempt for religion, as nothing more than superstition?

Despite Jiang’s naming of not only the ancient Greeks and Christianity as philosophies of slavery and mastery, but also Hobbes, Hegel, Nietzsche and Marx as masters of mastery, he then opts for mastery as the crowning achievement of the Party. “The spirit of the Chinese people has changed from passive to active means that the Chinese people have finally completely made the transition to a master’s personality, and have begun to firmly grasp their own historical fate.”

China has mastered the West, and no longer owes anything to anyone, having become fully Chinese once more. From there it is but a short step to triumphalism: “Faced with the global competitive landscape shaped by natural selection and the survival of the fittest, if the Chinese wanted to appear as masters, they had to have the courage to ‘unsheath their swords’ 亮剑 to confront each nation and engage in a life or death struggle. This ‘daring to unsheath one’s sword’ was what Xi Jinping’s report to the Nineteenth National Congress refers to repeatedly as the ‘spirit of struggle’. In the face of changes in the world system unseen in a thousand years, if the Chinese people want to realize the great revival of the Chinese nation and change the Western model of modernization through which the West has dominated the world, providing late-developing countries with the ‘China solution’ to modernization, they must engage in uncompromising struggle. One of the strongest points of the report to the Nineteenth Conference is that ‘struggle’ became one of its key terms, appearing twenty-three times. The report correctly points out that ‘realizing our great dream demands a great struggle’. This spirit of struggle is undoubtedly an expression of the master personality. The report to the Nineteenth Conference even used a literary expression to compare two phenomena in the flow of history: ‘The wheels of history roll on; the tides of the times are vast and mighty. History looks kindly on those with resolve, with drive and ambition, and with courage; it won’t wait for the hesitant, the apathetic, or those who shy from a challenge’. The former is the master who achieves victory through struggle, while the latter lacks the courage to struggle, and will necessarily suffer the fate of a slave. The description and comparison of the two encourage the members of the CCP not to forget their original intention, and to fight for the great revival of the Chinese nation with the spirit and character of a master who struggles.”

From there it is only a short step to a blood and soil nativism, a Han chauvinism that Mao might have denounced: “In Xi Jinping’s report to the Nineteenth CCP Congress, the key word ‘people’ appears 201 times, the notion that the Party and the people have established a ‘flesh and blood relationship’ appears three times, the most throughout the history of such reports. For this reason, the CCP is consistently grounded in this great native land, and its political nature, at base, is its indigenous, national nature, its authentic Chinese nature, rather than in the Party’s class nature. The fighting character of the CCP traces its origins not only to the spirit of mastery in Marxism, but even more to the Chinese cultural spirit, as reflected in sayings like ‘all are responsible for the rise and fall of the universe’ 天下兴亡,匹夫有责, and ‘the superior man tirelessly perfects himself’ 君子自强不. The CCP’s willingness to struggle and its talent for struggle have been bequeathed to it by the spiritual heritage of five thousand years of the history of Chinese civilization and by the fighting spirit of the more than one billion Chinese people from throughout the country. The report to the Nineteenth Congress particularly emphasizes that ‘our Party will remain the vanguard of the times, the backbone of the nation, and a Marxist governing Party’.”

From there it is only a short step to a blood and soil nativism, a Han chauvinism that Mao might have denounced: “In Xi Jinping’s report to the Nineteenth CCP Congress, the key word ‘people’ appears 201 times, the notion that the Party and the people have established a ‘flesh and blood relationship’ appears three times, the most throughout the history of such reports. For this reason, the CCP is consistently grounded in this great native land, and its political nature, at base, is its indigenous, national nature, its authentic Chinese nature, rather than in the Party’s class nature. The fighting character of the CCP traces its origins not only to the spirit of mastery in Marxism, but even more to the Chinese cultural spirit, as reflected in sayings like ‘all are responsible for the rise and fall of the universe’ 天下兴亡,匹夫有责, and ‘the superior man tirelessly perfects himself’ 君子自强不. The CCP’s willingness to struggle and its talent for struggle have been bequeathed to it by the spiritual heritage of five thousand years of the history of Chinese civilization and by the fighting spirit of the more than one billion Chinese people from throughout the country. The report to the Nineteenth Congress particularly emphasizes that ‘our Party will remain the vanguard of the times, the backbone of the nation, and a Marxist governing Party’.”

WHERE DO THE TIBETANS FIT?

Where do the Tibetans as a people, and the lands of the Tibetan Plateau, fit into this grandest of narratives? Neither the Tibetans nor other ethnic minority peoples are mentioned. Much is omitted, that does not fit, and we must look at the omissions as well as the exclusions.

Since Xi Jinping’s new era is predicated on there being a new contradiction, which only the party-state knows how to deal with, Jiang dwells on the Marxist idea of contradiction: “The basis of the CCP’s philosophy of struggle is grounded not only in the philosophy of mastery, but also in the theory of contradictions according to which any antagonism in the world can be unified in practice.”

Jiang revives Mao’s classification of contradictions into two categories, requiring different strategies, as not all contradictions necessitate struggle, violence or mastery: “Mao Zedong put forth his ‘theory of two contradictions’, pointing out the difference between the contradictions between the enemy and us, and contradictions among the people. In the case of contradictions among the people, struggle is not the most important thing; persuasion and education are the most important tools.”

The Tibetans remain stubbornly Tibetan, uncooked, unwilling to accept Han mastery and submit to pay tribute. So there is a contradiction. Thus the key question is whether the Tibetans are enemies, to be confronted; or are actually accepted as citizens, for whom persuasion and education are the most important tools? China’s treatment of the Tibetans, and the Uighurs of Xinjiang, seems to ambivalently flip-flop between these categories, sometimes treated as enemies to strike hard, sometimes as ignorant primitives to be coercively educated to accept their inevitable assimilation into the one Chinese race. By insisting the Tibetans and Uighurs are both insiders and outsiders, the contradiction is never resolved.

While the Tibetans are not named here, Buddhism is. The most explicit mention is in the final paragraph, extolling China’s great mission of the Xi Jinping era to spread Chinese civilisation globally. If the Neo Confucians centuries ago could push Buddhism to the margins, China can achieve anything: “The great revival of the Chinese nation is not only an economic and political revival. It will result in the great revival of Chinese civilization. If we say that Chinese civilization, when confronted with the challenge of Buddhism, engineered a great revival through the efforts of Song-Ming Neo Confucians, which then spread Chinese civilization from China proper throughout East Asia, then we should also say that when confronted in more recent times with the challenge of the modern West—Protestantism and liberalism—the Chinese nation is today again undergoing a great revival. The present great revival surely means that Chinese civilization is spreading and extending itself into even more parts of the world. This undoubtedly constitutes the greatest historical mission of the Chinese people in the Xi Jinping era.” Thus ends Jiang Shigong’s lesson.

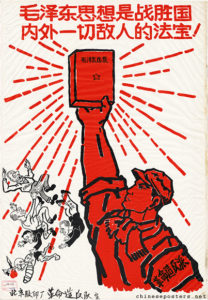

There is another, unacknowledged, appropriation of a Buddhist term. Jiang warns of the danger that the CCP could institutionalise itself as just another party of power, swayed by vested interests or even be in danger of being captured, with results as disastrous as the collapse of the Soviet Union. Thus the CCP must never lose sight of its theory of contradictions, theory of struggle and theory of practice. “As a principled political Party, if the CCP loses the philosophical analytical tools and methods provided by Marxism and Mao Zedong Thought, it will lose the theoretical magic weapon 理论法宝 pointing out the future direction of development and will necessarily lose the values supporting confidence in ideals and the theoretical weapon to consolidate the people’s hearts, thus opening the door to a politics of convenience.”

Mao called his mastery of contradictions a magical weapon, a term appropriated from Buddhist tradition, traditionally used to emphasise the power of the Buddha’s words and those of later Buddhist commentaries, to be effective medicine to cut through delusion and suffering. Although Mao embraced the modernist rejection of religion as poison, he readily grabbed Buddhist metaphors for his own use, and to this day the United Front is frequently called the CCP’s magic weapon.

Jiang is all for wielding the magic weapons of Sinified Marxism, complete with revived Maoist slogans: “The Chinese Communist Party has once again grasped the philosophical weapon of dialectical materialism, understanding the world through the worldview and methodology of the theory of contradiction and the theory of practice. Once again having done this, the fighting character will necessarily return yet again to the construction of the political thought of the CCP, becoming the political soul of the CCP. In other words, the nature of the struggle of the CCP derives from a philosophical consciousness of Marxism-Leninism. The philosophy of struggle in the philosophy of mastery and the philosophy of contradiction and practice are organically integrated. That there are contradictions means that conflict and struggle exist, and that struggle must engage real problems in practice, which in turn resolves the existing contradiction and propels practice forward. For this reason, Xi Jinping’s report to the Nineteenth Party Congress correctly points out that ‘the Chinese Communist Party is a great political Party that dares to struggle and dares to win’, and that ‘to realize a great dream, we must engage in great struggle’.”

There can be little doubt that the Tibetans must be struggled, as they refuse to accept the historic necessity and inevitability of becoming modern, urban, assimilated members of the Chinese race.

For Xi and Jiang, China is the most exemplary of nations, worthy of being emulated worldwide, the acme of civilisation. This is an old imperial tradition of the Chinese court, as is rule by ideology, which Xi and Jiang are now reviving.

We are indebted to Jiang’s translators, who offer this summary: “Jiang argues that Marxism must merge with traditional Confucianism and seek inspiration from its spirit of striving, of excellence, of self-perfection. All of this is combined with a defence of China’s cultural and civilizational uniqueness, the notion that, through the continual exercise of theory and practice, China has finally made socialism both uniquely Chinese and uniquely contemporary.

“The cunning of Jiang’s exposition of “Xi Jinping Thought” is that it addresses international liberal criticism without giving way to liberal political solutions.

“Ideology in China is largely a top-down affair. Ordinary people in China are not consulted and are unlikely to care about the doctrinal niceties of Marxism or “Xi Jinping Thought.” Xi’s state Marxism is an ideology that succeeds in fashioning a single narrative explaining China’s past, present, and future and—for the moment—leaves China’s chattering classes speechless and the general public quiescent. The revival of governing by ideology, which requires this single narrative, is Xi’s goal as well—a time-tested form of Chinese statecraft.”

Tibetans may be disinclined to engage with Jiang’s slippery story of how Xi Jinping is the incarnation of all that is best in Confucian tradition. Governing by ideology may be a time-tested mode of Chinese statecraft, but it leaves no space for Tibetans to be themselves, heard or even recognised as legitimately different. So why give yourself a headache tracking yet another hymn of praise to the supreme helmsman?

RULE BY IDEOLOGY IS NEW AGAIN

It is precisely because rule by ideology is such an embedded Han tradition of governing that it needs to be taken seriously, as seriously as the tenth Panchen Rinpoche did in his famous 70,000 character petition to Mao protesting starvation and famine in Tibet, using impeccable CCP jargon of the day. His mastery of Marxist jargon got him a hearing, and delayed for two years his gaoling for daring to contradict Mao. How many Tibetans today are equally adept?

Tibetans are inclined to see ideology as just dogma, as arbitrary and irrational rules imposed on others from above, to confuse the masses and to legitimate authority. Indeed, although the French inventor of ideology in 1796 saw it as a science of sciences, a radical critique of all that claims to be true; ideology, as a word and as a concept, has always had that second, pejorative meaning, always applied to the arguments of others with whom you disagree. This second meaning is almost as old as Destutt de Tracy’s first coinage, as it dates to Napoleon’s attack on Destutt as a peddler of abstract, impractical, even fanatical enthusiasms and theories.[2]

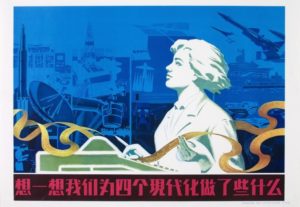

The ideologues of modernity, with or without Chinese characteristics, have long accused Buddhism, and all religions, of being irrational, useless or even poisonous dogmas and ideologies. The modernist embrace of science supposedly supplants old dogmas and ideologies with seeking truth from facts. Contemporary China, far from having left behind the dualisms of the Western tradition, fully embraces the atomistic, reductive logic of science, as the key to China’s future universal role. Jiang again: “What the CCP wants is to represent the ‘advanced productive forces’, and to strive to be in the front lines of the revolutions in science and technology, finally leading humanity’s scientific and technological development into the future.”

Jiang urges China, under Xi Jinping, to be at the forefront of all that is new, yet everything that is new is also old again: “In Xi Jinping’s report to the Nineteenth Congress, the words ‘new’ or ‘renew’ are widely used in expressions like ‘new era’, ‘new situation’, ‘new ideas’, and ‘new undertakings’. The expression ‘to renew’ alone was used fifty-three times. The concept of ‘new’ illustrates the ever-changing state of the entire world in its contradictory movements. This is precisely the essence of Chinese traditional philosophy. The Book of Changes, one of China’s ‘Five Classics’, took change as the starting point for understanding the whole world. The world is driven by contradictory movements to produce developments and changes which in turn drive struggle and innovation. Marxism and Chinese traditional culture have a high degree of internal consistency on this point, which precisely constitutes the deep philosophical roots of the Sinification of Marxism. Therefore, it is easy for the Chinese to shift from the ideal of the ‘renewal’ in morality and spirit emphasized by traditional culture to the ‘renewal’ of science, technology and material power that Marxism emphasizes.“

Tibetan Buddhism has many logical methods of exposing the flaws in this fatuous attempt at making China consistently both Marxist, and Confucian again. It is this ideological superstructure that blinds central leaders, making it impossible for them to hear what Tibetans in Tibet have been trying to tell them for decades. There is much that is good in Chinese tradition, such as crossing the river by feeling, with a bare foot, for each stone, one by one. But Jiang Shigong’s elaboration of Xi Jinping’s ideology is a heavy stone tied to the foot, dragging China down.

Tibetans do need to engage such slippery attempts at wielding a magic weapon. Tibetans inside Tibet cannot do this publicly, because they are under orders to repeat the vacuous slogans of Xi Jinping Thought and instruct others to do so. Tibetans beyond Tibet are free to penetrate Xi Jinping Thought and its acolytes, but have little inclination to engage, even though China is actually, under Xi Jinping, ruled by ideology. And there is no Panchen Lama to do it for us, as in 1962. Who will take up this challenge?

[1] David Hawkes, Ideology, 2nd ed, Routledge, 2003, 160

[2] “Ideology”, in Raymond Williams, Keywords: A vocabulary of culture and society, 2nd ed, Flamingo Fontana, 1983, 154