NORTSE: Tibetan art amid creative destruction

Wherever you go on the streets of Hong Kong, one product is thrust under your gaze everywhere, from almost every shopfront, whatever its main line of business: tins of powdered milk.

China has discovered milk, and with it, acute anxiety as to its safety, especially infant formula. The combination of nourishment and fear is a potent driver, driving mainland Chinese to Hong Kong to buy, at incredible markups, milk that is certain to be free of fear, for the sole reason that it is not manufactured in China.

As an Australian, from dairying country, milk is such an ordinary staple, taken for granted, selling in the supermarkets for less than US$1 per litre. Fresh milk in China, from a reputable source, fetches ten times as much. Little wonder the shopkeepers are cashing in.

Even bookshops sell tins of powdered milk. And why not, when the books are by Chinese free thinkers, whose works are banned in China, but available in Hong Kong if you know where to find them. Dissident books and milk powder on the same shelves makes for a one-stop shop for Chinese seeking nourishment for their babies, and mental nourishment for themselves.

To those from ancient dairying cultures, such as India and Tibet, China’s passion for milk in its myriad forms is amazing, even bemusing. Milk is foundational to both Tibetan and Indian civilisations, one of their deepest bonds. For thousands of years the natural sweetness of milk has been concentrated, in India, by boiling it as the first step in making almost all the famous Indian desserts. For millennia, Tibetans have milked, churned and cultured the milk of dri (the female yak) and sheep, creating cheese, yoghurt and mountains of butter in such abundance that it was almost a currency, the denomination of offerings made by pastoralists to sustain the monasteries, the monks and nuns, their sons and daughters in robes.

Now China has suddenly found milk, and with it, intensive agribusiness industrial milk production, concentrated largely in Inner Mongolia. The cow milk may have entered the commodity chain from the udders of cows owned by small farmers, but it was quickly aggregated by large corporations out to maximise profit and meet the surging demand in urban China for all things modern, which includes milk, especially yoghurt, the ultimate modern packaged health food drink. Those large corporations had a single regulatory metric to conform to, in order to be certified as top quality: the protein content. And they quickly discovered how to fool the official protein count test, by adding another white powder, made from petrochemicals, as the raw ingredient in every cheap Chinese plastic cup or plate or bowl you’ve ever bought. That nasty industrial secret is melamine, hardly a household word, yet plastic utensils made of melamine are probably in your kitchen cupboard (and safe to eat from).

The big Chinese dairying companies added melamine powder to powdered milk for years before the truth finally emerged. By China’s standards, few babies died of it, but hundreds of thousands, maybe millions of infants have kidney damage, for life.

The very babies, so precious to families permitted only one child, born to newly rich urban couples anxious to give their baby nothing but the best, were poisoned every day by their loving mother.

The very babies, so precious to families permitted only one child, born to newly rich urban couples anxious to give their baby nothing but the best, were poisoned every day by their loving mother.

The pain of being duped so callously was intense. The mistrust of “Made in China” goes deep. It is now seven years since the melamine scandal was exposed and supposedly rectified but still the mothers of China, wherever possible, buy infant formula imported from New Zealand or elsewhere worldwide, rather than China.

I was in Hong Kong not for milk but books. Every time I visit my Tibetan friends I stopover in Hong Kong and get for them the latest books in Chinese, not only the dissident books and the corruption scandal books, but also the latest of worldwide scholarship on history, anthropology, anything serious, all freshly translated into Chinese.

My Tibetan friends in India, many of them new to exile, often are literate in Tibetan and Chinese, not English. Their access to the whole spectrum of modernity, from art to medicine, economics to fiction, all comes via the Chinese language. They take their nourishment in Chinese medium.

My Tibetan friends in India, many of them new to exile, often are literate in Tibetan and Chinese, not English. Their access to the whole spectrum of modernity, from art to medicine, economics to fiction, all comes via the Chinese language. They take their nourishment in Chinese medium.

So if you are perhaps planning a trip to India, may I suggest a Hong Kong stopover, so easily built in on the way from the US? The airlines don’t seem to mind the extra kilos you lug on board, after all, a shopping stopover in Hong Kong is good for business. A list of the best bookshops is at the tail of this blog. If you don’t read Chinese (I don’t) you needn’t worry about making an idiot of yourself selecting titles you aren’t sure of. Westerners with little or no Chinese are not unknown in such bookshops, staff are ever helpful, and the books are displayed thematically, making it easy to find the Tibet section, and the Chinese Communist Party section, and there are other cues, such as the name of a nonChinese author, in English, on the cover.

You could introduce the latest in French intellectual theory to a Tibetan audience, or whatever appeals to you. Compared to the prices of books in western countries, these books are inexpensive too. I give those books to Dhondup Wangyal, librarian of the Chinese section at the Library of Tibetan Works & Archives.

Having filled my book bags, I lit out for my other rendezvous in Hong Kong, in a grimy industrial warehouse district I’d never been to, to see an exhibition of the latest art from Lhasa by Nortse, a Tibetan painter and photographer of his installations.

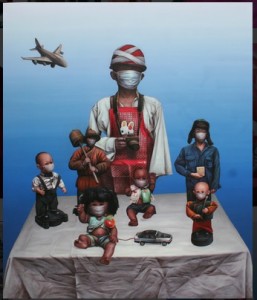

There too I was immediately confronted by melamine, fashioned industrially into utensils, refashioned by Nortse to make his own statement on the contemporary Tibetan condition.

There too I was immediately confronted by melamine, fashioned industrially into utensils, refashioned by Nortse to make his own statement on the contemporary Tibetan condition.

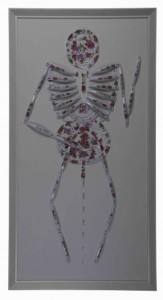

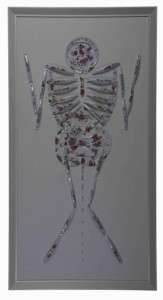

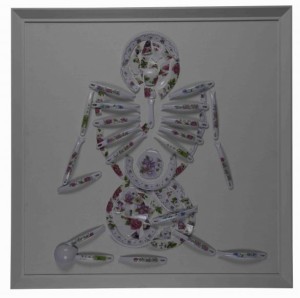

Melamine is Nortse’s latest medium, the cheaper, kitschier and more ordinary the better.  He bought long handled spoons, probably hundreds of them, snapped off and discarded the spoons, leaving only the handles.

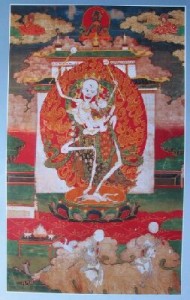

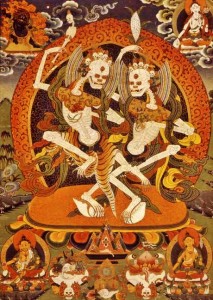

He bought long handled spoons, probably hundreds of them, snapped off and discarded the spoons, leaving only the handles.  These in turn have become skeletal ribs and bones, dancing Tibetan memento mori, evocative of the skeleton dancers in the cham monastic dance rituals, and the skull necklaces of Tibetan wrathful protector deities. There, on the walls of a bright white gallery they hang, frozen in the perpetual motion of bones in bardo.

These in turn have become skeletal ribs and bones, dancing Tibetan memento mori, evocative of the skeleton dancers in the cham monastic dance rituals, and the skull necklaces of Tibetan wrathful protector deities. There, on the walls of a bright white gallery they hang, frozen in the perpetual motion of bones in bardo.

Nortse, short for Norbu Tsering, knows his melamine. He explains: “The porcelain-like tableware I used were very cheap, made from some illegal workshops. It will do harm to people’s health if they use these unqualified products every day.” The catalogue of the exhibition begins with an essay, titled A Toxic Vision, by Emma Martin, ethnologist and museologist in Liverpool. She explains that melamine “has given him the tools to explore objects that were once integral to the act of nourishing the body, and whose purpose is now seemingly reversed. Through the usually unacknowledged detritus of life, bought in the market stalls of Lhasa, Nortse draws our attention to the harm that mass-produced consumer culture is inflicting on people’s physical well-being. These substandard materials also reflect on the damage that such large-scale production wreaks on the Tibetan cultural body as a whole.” Nourishment and fear confront me again, in the newly chic, barely gentrified Hong Kong backlot of Yip Fat Street in downmarket Wang Chuk Hang district, on the cusp of reinvention as the new uber cool.

Nortse’s dancing melamine skeletons, lords of the charnel ground, may be toxic. Even the US Food & Drug Administration, while playing down the dangers of melamine plastic-ware, does warn: “Foods and drinks should not be heated on melamine-based dinnerware in microwave ovens.”

Even though Nortse has snapped each plastic ladle, exposing me, the viewer, to the toxin, he is much too playful, too much the artist, way too Tibetan, to just stop there. What does not kill you makes you stronger.

The realised bodhisattva is the peacock which thrives in the jungle of poisonous plants. As the Tibetan tantrikas remind us, by fire is fire extinguished. There is much more to Nortse than toxic vision, or the pointedly political.

The realised bodhisattva is the peacock which thrives in the jungle of poisonous plants. As the Tibetan tantrikas remind us, by fire is fire extinguished. There is much more to Nortse than toxic vision, or the pointedly political.

The centrepiece of the exhibition is on the floor, a large number of charred pieces of wood, each in its own rectangular sand box, neatly laid out. It has similarities to an earlier installation, of the letters of the Tibetan alphabet, on the floor, also encased in sand and a metal frame as well, haunting images of the undying power of the Tibetan language as a chthonic force, coming up from the earth, uniquely able to express the deepest insights humanity has had into the nature of mind.

The centrepiece of the exhibition is on the floor, a large number of charred pieces of wood, each in its own rectangular sand box, neatly laid out. It has similarities to an earlier installation, of the letters of the Tibetan alphabet, on the floor, also encased in sand and a metal frame as well, haunting images of the undying power of the Tibetan language as a chthonic force, coming up from the earth, uniquely able to express the deepest insights humanity has had into the nature of mind.

The new installation of blackened wood is simply called Book of Ashes. Are these the ashes of finality, or rebirth? Only when you bend, closer to the ground, do the small flashes of colour in the overwhelming blackness come into focus. Fragments of Tibetan pecha texts, shreds of thangka paintings, a small but brightly painted Buddha have somehow survived the inferno, sometimes as a palimpsest underneath the text that has partly burned, revealing the baseline of truth.

Are these tiny images gleaming within the charcoal all that remains of Tibet? Are they old or new? Are they the rebirth of Tibetan culture, the renaissance of an undying insight into the nature of existence that nothing can destroy?

Maybe it’s because I’m Australian, used to seeing whole forests consumed by fire, charred everywhere you look, yet within weeks fresh green shoots burst from blackened trunks. These are optimistic works, signs of fresh life. The colours are vivid, the paint barely dry. Tibet will bounce back. As Tibetans say, it takes a nation of more than a billion people to hold them back.

Tibet is being reborn because it now circulates globally in the flows of global modernity, participating fully in the market economy’s cycles of creative destruction.  The location of Nortse’s Hong Kong show tells us much. In the Yally Industrial Building in Wang Chuk Hang the creaky old goods lifts still lumber up and down, their lattice work steel doors screech open and shut, the lifts driven by old men who have seen the whole cycle, from the days when Hong Kong was the sweatshop of the world, to today’s gallerista-led renaissance. Right now, gleaming new hotels and office blocks rise next to the old factories and public urinals. Tomorrow it will be gentrified. Nortse is right at home here, in the Rossi Rossi gallery.

The location of Nortse’s Hong Kong show tells us much. In the Yally Industrial Building in Wang Chuk Hang the creaky old goods lifts still lumber up and down, their lattice work steel doors screech open and shut, the lifts driven by old men who have seen the whole cycle, from the days when Hong Kong was the sweatshop of the world, to today’s gallerista-led renaissance. Right now, gleaming new hotels and office blocks rise next to the old factories and public urinals. Tomorrow it will be gentrified. Nortse is right at home here, in the Rossi Rossi gallery.

Nortse is at home everywhere. While based in Lhasa, he has been exhibited in Mayfair in London’s West End, in New York, New Zealand, Australia, Israel, in Potsdamer Platz in Berlin, you name it. He has exhibited in Lhasa and, yes, in Beijing. He is far from the only contemporary Tibetan artist to be at home anywhere, just like the lamas who bend minds worldwide. This is global circulation, capitalist creative destruction on a planetary scale.

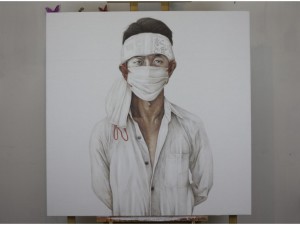

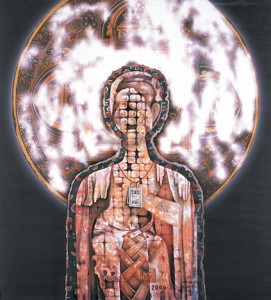

Nortse often paints himself, not out of vanity but because he is Tibetan everyman. He  photographs himself swathed in bandages, in uniform, his story the common story.

photographs himself swathed in bandages, in uniform, his story the common story.

He worked his way up in Lhasa, as a wedding photographer, a Xizang TV set designer, a billboard painter. He knows what people respond to. These days he sometimes uses his adult son, bandaged, to embody the same universals.

He worked his way up in Lhasa, as a wedding photographer, a Xizang TV set designer, a billboard painter. He knows what people respond to. These days he sometimes uses his adult son, bandaged, to embody the same universals.

Nothing can hold the Tibetans back.

Nothing can hold the Tibetans back.

WHERE IN HONG KONG TO FIND CHINESE BOOKS TIBETANS WANT TO READ:

Insiders Books (Owned by Mirror Books, Publisher)

内部書店 (明鏡)

銅羅灣波斯富街57號一樓

1/F, 57 Percival Street, Causeway Bay

Tel: +(852) 2838-0227

https://www.facebook.com/NeibuShudian

https://www.hkbookcity.com/

People’s Recreation Community

人民公社

銅鑼灣羅素街十八號一樓(時代廣場對面)

1/F, 18 Russell Street, Causeway Bay (opposite Times Square)

Opening Daily: 9:00 am – midnight

營業時間:每日 09:00 — 00:00

Tel: (+852) 2836 0016

http://www.peoplebookcafe.com/

| Greenfield Bookstore | |

| 門市部: 九龍旺角西洋菜街56號2樓 聯絡人: 譚先生 電話: +(852) 2385 8031 地鐵站:旺角E2出口 |

Shop: 56 Sai Yeung Choi St. South, 2/F Mongkok, Hong Kong Tel: +(852) 2385 8031 by MTR: Mongkok, Exit E2 |

| 1908 Bookstore | |

| 地址: 九龍尖沙咀北京道69號 环球商业大厦2楼202室 電話:+(852) 2311 7718 地鐵站:尖沙咀H出口 |

2/F Universal Commercial Bldg. 69 Peking Road TST Kowloon, Hong Kong Tel: +(852) 2311 7718 by MTR: Tsim Sha Tsui, Exit H |

Causeway Bay Books

銅鑼灣書店

銅鑼灣駱克道529號(地鐵站D1出口對面 – 祟光百貨公司後面)

1/F, 529 Lockhart Road, Causeway Bay (opposite MTR exit D1)

Tel: +(852) 2834-4488

http://cwbbooks.com/

Cosmos Books

天地圖書

灣仔莊士敦道 30 號地庫及一樓

B/F & 1/F, No. 30, Johnston Road, Wan Chai

Open Daily from 10 am to 8 pm

營業時間:上午十時至下午八時

Tel: +(852) 2866-1677

www.cosmosbooks.com.hk

1908 Bookstore

1908書社

尖沙咀北京道69號環球商業大廈2樓202室

Room 202, Universal Commercial Building,

69 Peking Road, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon

Tel:+(852) 2311-7188

http://1908bookstore.blogspot.hk/